полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

The Western White-crowned Sparrow was first met with by Mr. Ridgway, at the Summit Meadows, near the summit of Donner Lake Pass of the Sierra Nevada, at an altitude of about seven thousand feet. It was there an abundant and characteristic bird. The males were in full song in all parts of the meadow, and were nesting in such numbers that on the evening of July 9, on halting for the night, in a hurried search no less than twenty-seven of their eggs were obtained within about fifteen minutes. In every instance the nests were embedded under a species of dwarf-willow, with which the ground was covered. The birds were extremely unsuspicious, the male often sitting on a bush within a few feet of the collector, and chanting merrily as the eggs were being blown. In one instance, having occasion to repass a spot from which a nest had been taken, the female was found sitting in the cavity from which its nest had been removed. This species is only a winter visitant of the lower country, but is there universally distributed, and always found in bushy localities.

Mr. Bannister states that this bird was tolerably abundant among the alder-bushes in certain parts of St. Michael’s Island. Mr. Dall found it common at Nulato, and especially so at Fort Yukon. It arrived at Nulato about May 20. Its nests and eggs were obtained from Indians at Nowikakat, on the Yukon River. Dr. Kennerly met with these birds, in February, at White Cliff Creek, New Mexico. They were first observed on approaching the Big Sandy, and from thence to the Colorado they were found in abundance. They were mostly in flocks, and were generally found among the bushes, in the vicinity of water. He also met with it in the valley of the Rio Grande, Corralitos, and Janos Rivers. It seemed to prefer the vicinity of settlements, where it was always seen in greater numbers than elsewhere.

Mr. Dresser found these birds common about San Antonio, Texas, during the winter, arriving late in September. Some may remain and breed, as several were observed there in June. Dr. Coues also found them abundant in Arizona, where he first observed them September 15. After this they became exceedingly numerous, and remained so until January. Later than this only a few stragglers were seen, until April, when they again became abundant. By far the greater part left, and proceeded north to breed.

These Sparrows were found breeding on the Yukon and at Fort Anderson in great numbers by Messrs. MacFarlane, Lockhart, and Ross. Their nests were in nearly all cases found upon the ground, often in tufts of grass, clumps of Labrador tea, or other low bushes. They were composed of hay, and, in nearly every instance, were lined with deer’s hair, and in a few with feathers. A few were without any lining. In selecting a situation for their nests, they seemed generally to give the preference to open or thinly wooded tracts. The male bird was usually seen, or its note heard, in the immediate vicinity of the nest. The eggs were obtained from the 4th of June to the 1st of July. Their maximum number was six; the most common, four.

Mr. B. R. Ross states that this species arrives at the Arctic Circle from about the 15th to the 20th of May, and at Slave Lake only a few days earlier. They are then no longer in flocks, but have already paired. They commence nesting almost immediately upon their arrival at the Yukon and at Fort Good Hope. Mr. Ross found nests made as early as May 20 to 25, while there was still considerable snow upon the ground. They mostly nest, however, in the first half of June, the young usually hatching between the 15th and 30th, and leaving the nests when less than a month old. They all leave the Arctic Circle about the middle of September. A few were seen at Fort Simpson in the latter part of that month. When starting, they gather in small flocks. The nest is built on high ground, among low, open bushes, always at the foot of some shrub or bush, and more or less protected and concealed by grass. It is never placed in the edges of marshes, like Melospiza lincolni; nor on small prairies, like the Passerculus savanna; nor in thick woods, as does sometimes the Z. albicollis. The nest is neatly built, is more compact and of finer materials than that of the latter. It is large and deep, formed externally of coarse grass, and lined with finer materials.

When started from her nest, the female flies off a few yards and flutters silently along the ground to divert attention. If unsuccessful, she flies about her nest uttering sharp, harsh notes of anxiety. The male is less bold on such occasions. Their favorite habitat is light open bushes, affecting neither open plains nor deep woods and never perching so high as twenty feet from the ground, and usually, in all their movements, keeping close to the earth.

Its food, so far as could be observed, consisted almost wholly of seeds, sought mostly on the ground. It hatches only a single brood in a year.

Mr. B. R. Boss adds that this is the most abundant Sparrow throughout the Mackenzie River region, and also the most interesting. Through the spring and summer its melodious song, which strongly calls to mind the first notes of the old air, “O Dear! what can the Matter be?” may be heard from every thicket, both night and day. When sleeping in the woods, Mr. Boss states that he has often been awakened by several of these birds singing near him, answering each other, throughout the short night, when all the other birds were silent. On this account, but for the richness and melody of its song the bird would have made itself quite disagreeable.

The Cree Indians name this Sparrow Wah-si-pis-chan, because they think this resembles its notes, the last of which are supposed to imitate the sound of running water. It sings long after the breeding-season is past, and its notes may be heard even into August.

The eggs measure .85 of an inch in length by .65 in breadth, and have a ground of a greenish-white marked with a rusty-brown. They are of a rounded-oval shape.

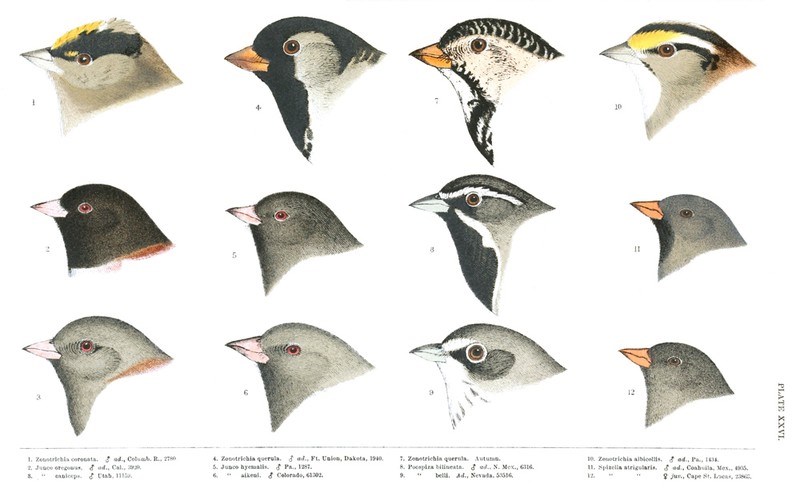

PLATE XXVI.

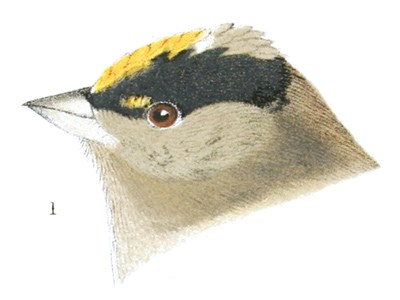

1. Zonotrichia coronata. ♂ ad., Columb. R., 2780.

2. Junco oregonus. ♂ ad., Cal., 3920.

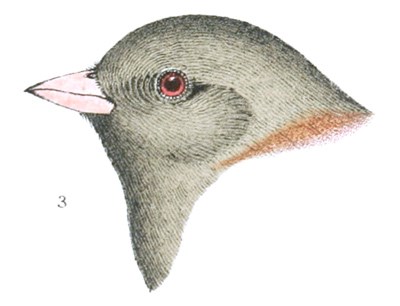

3. Junco caniceps. ♂ Utah, 11159.

4. Zonotrichia querula. ♂ ad., Ft. Union, Dakota, 1940

5. Junco hyemalis. ♂ Pa., 1287.

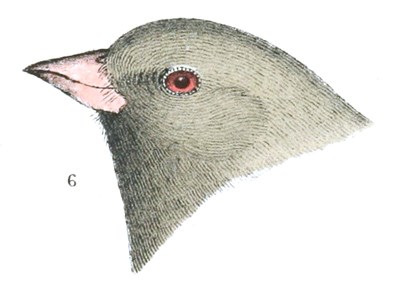

6. Junco aikeni. ♂ Colorado, 61302

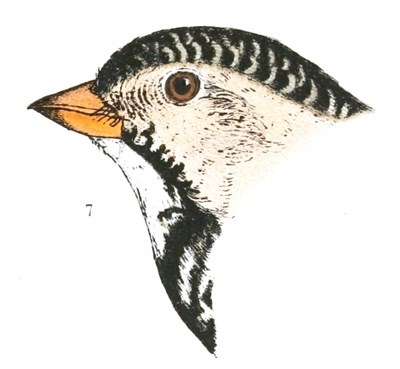

7. Zonotrichia querula. Autumn.

8. Poospiza bilineata. ♂ ad., N. Mex., 6316.

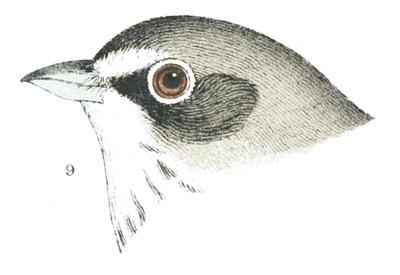

9. Poospiza belli. Ad., Nevada, 53516.

10. Zonotrichia albicollis. ♂ ad., Pa., 1434.

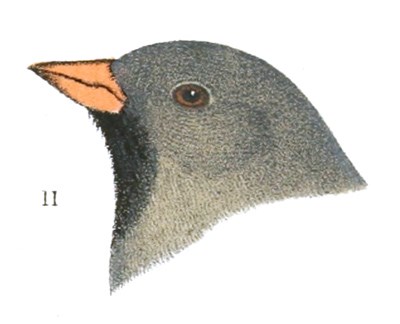

11. Spizella atrigularis. ♂ ad., Coahuila, Mex., 4935.

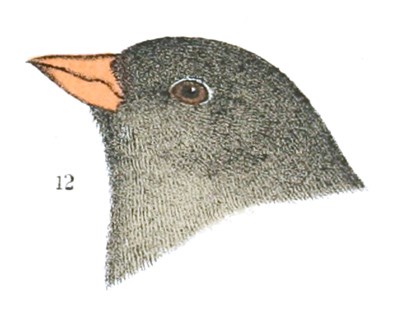

12. Spizella atrigularis. ♀ juv., Cape St. Lucas, 23866.

Zonotrichia coronata, BairdGOLDEN-CROWNED SPARROW

Emberiza coronata, Pallas, Zoög. Rosso-Asiat. II, 1811, 44, plate. Zonotrichia c., Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 461.—Heerm. X, S, 48 (nest).—Cooper & Suckley, 201.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 284 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 197. Emberiza atricapilla, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 47, pl. cccxciv (not of Gmelin). Fringilla atricapilla, Aud. Synopsis, 1839, 122.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 162, pl. cxciii. Fringilla aurocapilla, Nuttall, Man. I, (2d. ed.,) 1840, 555. Zonotrichia aurocapilla, Bon. Consp. 1850, 478.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route, Rep. P. R. R. VI, IV. 1857, 88. Emberiza atricapilla, Gm. I, 1788, 875 (in part only).—Lath. Ind. 415. Black-crowned Bunting, Pennant, Arc. Zoöl. II, 364.—Lath. II, I, 202, 49, tab. lv.

Sp. Char. Hood, from bill to upper part of nape, pure black, the middle longitudinal third occupied by yellow on the anterior half, and pale ash on the posterior. Sides and under parts of head and neck, with upper part of breast, ash-color, passing insensibly into whitish on the middle of the body; sides and under tail-coverts tinged with brownish. A yellowish spot above the eye, bounded anteriorly by a short black line from the eye to the black of the forehead. This yellow spot, however, reduced to a few feathers in spring dress. Interscapular region, with the feathers, streaked with dark brown, suffused with dark rufous externally. Two narrow white bands on the wings. Bill dusky above, paler beneath; legs flesh-color.

Autumnal specimens have more or less of the whole top of head greenish-yellow; the feathers somewhat spotted with dusky; the black stripe of the hood reduced to a narrow superciliary line, or else to a spot anterior to the eye. Length about 7 inches; wing, 3.30.

Hab. Pacific coast from Russian America to Southern California; West Humboldt Mountains, Nev. Black Hills of Rocky Mountains?

Habits. This species, described and figured by Mr. Audubon as the Fringilla atricapilla, is found in western North America, from Alaska to Southern California and Cape St. Lucas, and is almost entirely confined to the Pacific Province, being known east of the Cascade Mountains and Sierra Nevada only as stragglers. In its general habits it is said to greatly resemble the Z. gambeli. In the vicinity of Fort Dalles, and also in the neighborhood of Fort Steilacoom, Dr. Suckley found it quite abundant in the summer.

Dr. Cooper says that it is only a straggler in the forest regions west of the Cascade Mountains, but that it probably migrates more abundantly to the open plains eastward of them. He met with them but once near Puget Sound, May 10, when they were apparently migrating. Dr. Cooper found a few of this species wintering as far south as San Diego, associating with Z. gambeli. They were much less familiar, did not come about the houses, but kept among the dense thickets. They were then silent, nor has he ever heard them utter any song. He met with none near the summit of the Sierra Nevada.

Dr. Newberry found these birds abundant in the vicinity of San Francisco in winter.

Mr. Nuttall met with the young birds of this species on the central tablelands of the Rocky Mountains, in the prairies. They were running on the ground. He heard no note from them. He afterwards saw a few stragglers, in the early part of winter, in the thickets of the forests of the Columbia River, near Fort Vancouver. He also met with them, in the winter and until late in the spring, in the woods and thickets of California.

Dr. Heermann found this species very abundant in the fall season, generally associated with the California Song Sparrow and the Z. gambeli. It resorts to the deep shady thickets and woods, where it passes the greater part of its time. In the mountainous districts it prefers the hillsides, covered with dense undergrowth. It occasionally breeds in California, as Dr. Heermann found its nest in a bush near Sacramento City. It was composed of coarse stalks of weeds, and lined internally with fine roots. The eggs were four in number, and are described as having been of an ashy-white ground, with markings of brown umber, at times appearing almost black from the depth of their shade. They were marked also with a few spots of a neutral tint.

Many of these birds were obtained in Sitka and in Kodiak, by Bischoff, and also in British Columbia by Elliot.

Only one specimen of this species was met with by Mr. Ridgway in his explorations with Mr. Clarence King’s survey. This was taken October 7, 1867, in the West Humboldt Mountains, in company with a flock of Z. gambeli.

Zonotrichia albicollis, BonapWHITE-THROATED SPARROWFringilla albicollis, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 926.—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 51, pl. xxii, f. 2.—Licht. Verz. Doubl. No. 247.(1823). Zonotrichia albicollis, Bp. Consp. 1850, 478.—Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 132.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 463.—Samuels, 311. Passer pennsylvanicus, Brisson, 1760, Appendix, 77. Fringilla pennsylvanica, Lath. Index, I, 1790, 445.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 42; V, 497, pl. viii.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 121.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 153, pl. cxci.—Max. Cab. Jour. VI, 1858, 276. Fringilla (Zonotrichia) pennsylvanica, Sw. F. B. Am. II, 1831, 256. Zonotrichia pennsylvanica, Bon. List, 1838.

Sp. Char. Two black stripes on the crown, separated by a median one of white. A broad superciliary stripe from the base of the mandible to the occiput, yellow as far as the middle of the eye and white behind this. A broad black streak on the side of the head from behind the eye. Chin white, abruptly defined against the dark ash of the sides of the head and upper part of the breast, fading into white on the belly, and margined by a narrow black maxillary line. Edge of wing and axillaries yellow. Back and edges of secondaries rufous-brown, the former streaked with dark brown. Two narrow white bands across the wing-coverts. Length, 7 inches; wing, 3.10; tail, 3.20. Young of the year not in the collection.

Hab. Eastern Province of North America to the Missouri. Breeding in most of the northern United States and British Provinces, and wintering in the United States almost to their southern limit. Aberdineshire, England, August 17, 1867 (Zoölogist, Feb., 1869, 1547; P. Z. S. 1857, 52). Scotland (Newton, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1870, 52).

Female smaller, and the colors rather duller. Immature and winter specimens have the white chin-patch less abruptly defined, the white markings on the top and sides of the head tinged with brown. Some specimens, apparently mature, show quite distinct streaks on the breast and sides of throat and body.

Habits. The White-throated Sparrow is, at certain seasons, an abundant bird in all parts of North America, from the Great Plains to the Atlantic, and from Georgia to the extreme Arctic regions. A few breed in favorable situations in Massachusetts, especially in the extreme northwestern part of the State. It breeds abundantly in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, and in all the British Provinces.

Sir John Richardson states that they reach the Saskatchewan in the middle of May, and spread throughout the fur countries, as far, at least, as the 66th parallel, to breed. He states that he saw a female sitting on seven eggs near the Cumberland House, as early as June 4. The nest was placed under a fallen tree, was made of grass, lined with deer’s hair and a few feathers. Another, found at Great Bear’s Lake, was lined with the setæ of the Bryum uliginosum. He describes the eggs as of a pale mountain-green, thickly marbled with reddish-brown. When the female was disturbed, she ran silently off in a crouching manner, like a Lark. He describes the note of this bird as a clear song of two or three notes, uttered very distinctly, but without variety,—a very incomplete description.

Mr. Kennicott states that this species does not extend its migrations as far to the north as Z. gambeli, and is even much less numerous on the south shores of the Slave Lake, where he did not observe half so many of this as of the other. It also nests later, as he found the first nest observed on the 22d of June, with the eggs quite fresh, incubation not having commenced, and found others after that date. On English River he found two nests with eggs on the 9th and 17th of July, and one near the Cumberland House on the 30th of June. Two of these were in low swampy ground among large trees, the other on high ground among small bushes. They were constructed on large bases of moss, and lined with soft grasses. When startled from her nest, the female always crept silently away through the grass.

He met with this species in considerable flocks, accompanied by small numbers of Z. leucophrys, on the north shore of Lake Superior, on the 11th of May. He saw individuals on the 29th of May, near the Lake of the Woods, and it doubtless breeds as far south as that region. In the fall it was not seen at Fort Simpson later than the last of September. As it is a much more eastern bird than Z. gambeli, it is probably in greater abundance on the eastern end of Slave Lake. Its song he regards as by no means so attractive as that of Z. gambeli or of Z. leucophrys. Its general habits are very much like those of the former, and though by no means a strictly terrestrial bird, it rarely perches high on trees, and generally flies near the ground, except in its long migratory flights.

Notwithstanding the slighting manner in which the song of this bird is spoken of by some writers, in certain parts of the country its clear, prolonged, and peculiar whistle has given to it quite a local fame and popularity. Among the White Mountains, where it breeds abundantly, it is known as the Peabody Bird, and its remarkably clear whistle resounds in all their glens and secluded recesses. Its song consists of twelve distinct notes, which are not unfrequently interpreted into various ludicrous travesties. As this song is repeated with no variations, and quite frequently from early morning until late in the evening, it soon becomes quite monotonous.

Among the White Mountains I have repeatedly found its nests. They were always on the ground, usually sheltered by surrounding grass, and at the foot of bushes or a tree, or in the woods under a fallen log. In that region it retained all its wild, shy habits, rarely being found in the neighborhood of dwellings or in cultivated grounds. But at Halifax this was not so. There I found them breeding in gardens, on the edge of the city, and in close proximity to houses, apparently not more shy than the common Song Sparrow.

Wilson states that these birds winter in most of the States south of New England, and he found them particularly numerous near the Roanoke River, collecting in flocks on the borders of swampy thickets, among long rank weeds, the seeds of which formed their principal food. He gives the 20th of April as the date of their disappearance, but I have observed them lingering in the Capitol grounds in Washington several weeks after that date. They pass through Eastern Massachusetts from the 10th to the 20th of May, and repass early in October. A few stragglers sometimes appear at earlier dates, but irregularly. In Western Maine, where it is quite common, Professor Verrill states that it sometimes arrives by the middle of April. Near Springfield, Mass., Mr. Allen noted their appearance between the last of April and the 20th of May; in fall, from the last of September through October. Their favorite haunts are moist thickets. The young males do not acquire their full plumage until the second spring, but sing and breed in the plumage of the females, as Mr. Allen ascertained by dissection. Mr. Hildreth observed a pair near Springfield during three successive summers, and although he could not find the nest, he saw them feeding their scarcely fledged young birds.

At Columbia, S. C., Dr. Coues found these Sparrows very abundant, from October through April. They sing, more or less, all winter, and during the last few weeks of their stay are quite musical. Many hundreds pass the months of March and April in the gardens of that city, though during the winter they were mostly to be found in thickets and fields, in company with many other species.

A single specimen of this bird was killed in Aberdeenshire, August 17, 1867, and a second was lately captured alive near Brighton (P. Z. S., June 4, 1872).

Mr. Audubon says that this bird visits Louisiana and all the Southern districts in winter, remaining from November to March, in great numbers. They form groups of from thirty to fifty, and live together in great harmony, feeding upon small seeds. At this time they are plump to excess, and are regarded as a great delicacy.

When kept in confinement these birds become quite tame, and in the spring will sing at all hours of the day or night.

The nest of this bird is usually, if not always, on the ground, but in various situations, as I have found them on a hillside, in the midst of low underbrush, in a swampy thicket, at the foot of some large tree in a garden, as at Halifax, by the edge of a small pond, or in a hollow and decaying stump. Their nest is large, deep, and capacious, with a base of moss or coarse grasses, woven with finer stems above and lined with hair, a few feathers, fine rootlets of plants or soft grasses. The eggs vary from four to seven in number. Their ground-color is of a pale green or a greenish-white, marked over the entire egg with a fox-colored or rusty brown. Occasionally these markings are sparsely scattered, permitting the ground to be plainly visible, but generally they are so very abundant as to cover the entire egg so closely as to conceal all other shade, and give to the whole a deep uniform rufous-brown hue, through which the under color of light green is hardly distinguishable. They measure .90 by .68 of an inch.

Zonotrichia querula, GambelHARRIS’S SPARROW; BLACK-HOODED SPARROWFringilla querula, Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 555 (Westport, Mo.). Zonotrichia querula, Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. 2d Ser. I, 1847, 51.—Bonap. Consp. 1850, 478.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 462.—Allen, Amer. Naturalist, May, 1872. Fringilla harrisi, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, 331, pl. cccclxxxiv. Fringilla comata, Pr. Max. Reise II, 1841.—Ib. Cab. Jour. VI, 1858, 279. Zonotrichia comata, Bp. Consp. 1850, 479.

Sp. Char. Hood and nape, sides of head anterior to and including the eyes, chin, throat, and a few spots in the middle of the upper part of the breast and on its sides, black. Sides of head and neck ash-gray, with the trace of a narrow crescent back of the ear-coverts. Interscapular region of back with the feathers reddish-brown streaked with dark brown. Breast and belly clear white. Sides of body light brownish, streaked. Two narrow white bands across the greater and middle coverts. Length about 7 inches; wing, 3.40; tail, 3.65.

Hab. Missouri River, above Fort Leavenworth. Chillicothe, Mo. (Hoy). Very common in Eastern Kansas (Allen). San Antonio, Texas, spring (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 488).

The bill of this species appears to be yellowish-red. More immature specimens vary in having the black of the head above more restricted, the nape and sides of the head to the bill pale reddish-brown, lighter on the latter region. Others have the feathers of the anterior portion of the hood edged with whitish. In all there is generally a trace of black anterior to the eye.

This species has a considerably larger bill than Z. leucophrys, the mandible especially.

Habits. This species was first described in 1840, by Mr. Nuttall, from specimens obtained by him near Independence, Mo., near the close of the month of April. He again met with them on the following 5th of May, when not far from the banks of the Little Vermilion River, a branch of the Kansas. He found them frequenting thickets, and uttering, chiefly in the early morning, but also occasionally at other parts of the day, a long, drawling, faint, solemn, and monotonous succession of notes, resembling tē-dē-dē-dē.