полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

The essential characters of this genus are the middle toe rather shorter than the short tarsus; the lateral toes slightly unequal, the outer reaching the base of the middle claw; the tail a little shorter than the wings, slightly emarginate. In Junco cinereus the claws are longer; the lower mandible a little lower than the upper.

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Prevailing color plumbeous; abdomen, crissum, and lateral tail-feathers white.

A. Bill entirely light flesh-colored, dusky only at extreme point. Color of jugulum (deep ash or plumbeous-black) abruptly defined against the pure white of the abdomen.

a. Posterior outline of the dark color of the jugulum convex; sides pinkish.

1. J. oregonus. Back and wings more or less tinged with dark rusty, in sharp contrast with the black (♂) or ash (♀) of the head and neck. Hab. Pacific Province of North America, from Sitka southward; east across the Middle Province of United States, to the Rocky Mountains (where mixed with J. caniceps116) occasionally to the Plains (where mixed with J. hyemalis117).

b. Posterior outline of the dark color of the jugulum concave; sides ashy.

2. J. hyemalis. Back and wings without rusty tinge.

Wing without any white; three outer tail-feathers only, marked with white. Bill, .40 and .25; wing, 3.10; tail, 2.80; tarsus, .80. Hab. Eastern Province North America. Straggling west to Arizona (Coues); in the northern Rocky Mountains, mixed with J. oregonus … var. hyemalis.

Wing with two white bands (on tips of middle and greater coverts); four outer tail-feathers marked with white. Bill, .50 and .30; wing, 3.40; tail, 3.20. Hab. High mountains of Colorado (El Paso Co., Aiken) … var. aikeni.

3. J. caniceps. Back (interscapulars) rufous; scapulars and wings uniform ashy. Hab. Central Rocky Mountains of United States. (Along southern boundary mixed with J. cinereus.118)

B. Bill with the upper mandible black, the lower yellow. Ash of the jugulum fading gradually into the grayish-white of the abdomen.

4. J. cinereus. Whole back, scapulars, wing-coverts, and tertials rufous.

Throat and jugulum pale ash; back bright rufous. Wing, 3.10; tail, 3.00; bill, .34 and .25; tarsus, .80. Hab. Tablelands and mountains of Mexico … var. cinereus.119

Throat and jugulum deep ash; back dull, or olivaceous-rufous. Wing, 3.15; tail, 3.10; bill, .44 and .34; tarsus, .90. Hab. High mountains of Guatemala … var. alticola.120

Junco hyemalis, SclaterSNOWBIRDFringilla hyemalis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, (10th ed.,) 1758, 183 (not of Gmelin or Latham).—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 72; V, 505, pl. xiii.—Max. Cab. Jour. VI, 1858, 277. Fringilla (Spiza) hyemalis, Bon. Syn. 1828, 109. Emberiza hyemalis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 308. Struthus hyemalis, Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 475. Niphæa hyemalis, Aud. Synopsis, 1839, 106.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 88, pl. clxvii. Junco hyemalis, Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1857, 7.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 468.—Coues, P. A. N. S. 1861, 224.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 284.—Samuels, 314. Fringilla hudsonia, Forster, Philos. Trans. LXII, 1772, 428.—Gmelin, I, 1788, 926.—Wilson’s Index, VI, 1812, p. xiii. Fringilla nivalis, Wilson, II, 1810, 129, pl. xvi, f. 6.

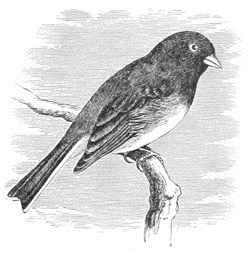

Sp. Char. Everywhere of a grayish or dark ashy-black, deepest anteriorly; the middle of the breast behind and of the belly, the under tail-coverts, and first and second external tail-feathers, white; the third tail-feather white, margined with black. Length, 6.25; wing, about 3. Female paler. In winter washed with brownish. Young streaked above and below.

Hab. Eastern United States to the Missouri, and as far west as Black Hills. Stragglers at Fort Whipple, Arizona, and mountains of Colorado.

Junco oregonus.

The wing is rounded; the second quill longest; the third, fourth, and fifth, successively, a little shorter; the first longer than the sixth. Tail slightly rounded, and a little emarginate. In the full spring dress there is no trace of any second color on the back, except an exceedingly faint and scarcely appreciable wash of dull brownish over the whole upper parts. The markings of the third tail-feather vary somewhat in specimens. Sometimes the whole tip is margined with brown; sometimes the white extends to the end; sometimes both webs are margined with brown; sometimes the outer is white entirely; sometimes the brownish wash on the back is more distinct.

Some specimens (No. 52,702 and 52,701, males) from Sun River, Dakota, appear to be hybrids with oregonus. They have the general appearance of hyemalis, the back being nearly uniform with the head (with a wash of sepia-brown, however), and the head and neck of the same dark plumbeous; the sides, however, are pinkish, and the plumbeous on the jugulum has its posterior outline convex, as in oregonus. If, as there is every reason to believe, these specimens are really hybrids, then we have the two extreme forms of the genus connected by specimens of such a condition; thus, hyemalis with oregonus, oregonus with caniceps (= annectens, Baird), and caniceps with cinereus (= dorsalis, Henry). It may perhaps be considered a serious question whether all (including alticola) are not, in reality, geographical races of one species. However, as there is no possibility of ever proving this, it may be best to consider them as representative species, and these specimens of intermediate characters as hybrids.

Habits. The common familiar Snowbird of the Eastern States is found throughout all North America, east of the Black Hills, from Texas to the Arctic regions. Wherever found, it is at certain seasons a very abundant and an equally familiar bird.

It nests as far south, in mountainous regions, as Virginia, and thence to New York and the northern parts of the New England States, breeding only in the highlands, but descending more and more into the plains as we proceed north. As it is a very hardy bird, its migrations are irregular and uncertain. In some seasons I have observed but few at irregular intervals; and in others, in which the spring was cold and backward, I have met with them in every month except July and August.

Mr. Kennicott found but few birds of this species breeding as far south as Fort Resolution or Slave Lake, and was unable to find any of their nests, though he met with a few birds that were evidently breeding there. He found it afterwards nesting in the greatest abundance about latitude 65°. They were very numerous on the Yukon, and Mr. MacFarlane found them breeding plentifully on the Anderson River, at the edge of the barren-ground region.

The nests found by Mr. Kennicott were all on the ground, more or less concealed in tufts of grass, dry leaves, or projecting roots. Some were in thick woods, others in more open regions, and were lined with moose-hair.

Mr. Ross states that this species frequents all the Mackenzie River region in summer, arriving about the 20th of April, and leaving about the 10th of October. Besides its call-note, or chirp, it has a very pretty song.

Mr. Dall also remarks that they were quite common at Nulato in the spring, not arriving there, however, until about the first of June.

According to Mr. Dresser, it is found occasionally about San Antonio in winter, and Dr. Woodhouse says that it is also common in the Indian Territory in fall and winter. According to Mr. Audubon, it makes its appearance in Louisiana in November, and remains there until early spring. It is also abundant in South Carolina, arriving there in October and leaving in April.

This species was observed by Mr. Aiken in Colorado Territory for about three weeks following March 20, after which they were seen no more.

It breeds more or less abundantly in the northern and eastern portions of Maine. About Calais and in all the islands of the Bay of Fundy, and throughout New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, I found this by far the most common and familiar species, especially at Pictou, where it abounded in the gardens, in repeated instances coming within the outbuildings to build its nests. In a woodshed connected with the dwelling of Mr. Dawson, my attention was called to the nests of several of these birds, built within reach of the hand, and in places where the family were passing and repassing throughout the day. In Pictou they were generally called the Bluebird by the common people. On my ride from Halifax to Pictou, I also found these birds breeding by the roadside, often under the shelter of a projecting bank, in the manner of the Passerculus savanna. I afterward found them nesting in similar situations among the White Mountains, the roadsides seeming to be a favorite situation. In habits and notes, at Pictou, they reminded me of the common Spizella socialis, but were, if anything, more fearless and confiding, coming into the room where the family were at their meals, and only flying away when they had secured a crumb of sufficient size.

In Western Massachusetts they breed in all parts of the range of Green Mountains, from Blandford to North Adams. They appear about Springfield in October and November, and are for a while abundant, and are then gone until March, when they return in full song, and remain numerous into April, and less common until into May. In the eastern part of the State they are found from October to late in May, with some irregularity and in varying numbers. Mr. Audubon did not meet with any on the coast of Labrador, and Dr. Coues did not find them so abundant as he expected, and did not observe any until the latter part of July, at which time the young were already hatched, and they were associated in small companies. They kept entirely in the thick woods, and seemed rather timid.

Their food is small berries, seeds of grasses and small plants, insects, and larvæ. They seek the latter on the ground, and in the winter are said to frequent the poultry-yards, and avail themselves of the services of the fowls in turning up the earth. On the ground they hop about in a peculiar manner, apparently without moving their feet. At night and during storms they shelter themselves in the thick branches of evergreens, and also in stacks of hay and piles of brushwood.

During the winter the Snowbird appears to be rather more numerous in the Middle and Southern States than in New England. In the former they appear late in October, at first on the borders of woods, searching for food among the fallen and decaying leaves. Later in the season, as the weather becomes colder, and the snow deprives them of this means of feeding, they resort to the roadsides and feed on the seeds of the taller weeds, and to the farm-houses and farm-yards, and even enter within the limits of large cities, where they become very tame and familiar. They are much exposed to attacks from several kinds of Hawks, and the apparent timidity they evince at certain times and places is due to their apprehensions of this danger. The sudden rustle of the wings of a harmless fowl will cause the whole flock to take at once to flight, returning as soon as their alarm is found to be needless, but repeated again and again when the same dreaded sounds are heard.

Neither Wilson, Nuttall, nor Audubon appear to have ever met with the nests or eggs of this bird, though the first met with them breeding both among the Alleghanies, in Virginia, and the highlands of Pennsylvania and New York. In Otsego County, in the latter State, Mr. Edward Appleton was the first to discover and identify their nest and eggs, as cited by Mr. Audubon in the third volume of his Birds of America. They were found in considerable numbers in the town of Otsego. Their nests were on the ground in sheltered positions, some of them with covered entrances. Their complement of eggs was four. One of their nests was sent me, and was characteristic of all I have since seen, having an external diameter of four and a half inches and a depth of two. The cavity was deep and capacious for the bird. The base and periphery of the nest were made of slender strips of bark, coarse straws, fine roots, and horsehair, lined with fine mosses and the fur of smaller animals. The eggs were of a rounded-oval shape; their ground-color is a creamy yellowish-white, marked with spots and blotches of a reddish-brown confluent around the larger portion of the egg, but rarely covering either end. They measure .75 by .60 of an inch, not varying in size from those of J. oregonus.

Junco hyemalis, var. aikeni, RidgwayWHITE-WINGED SNOWBIRDSp. Char. Generally similar to J. hyemalis, but considerably larger, with more robust bill; two white bands on the wing, and three, instead of two, outer tail-feathers entirely white. No. 61,302 ♂, El Paso Co., Colorado, December 11, 1871, C. E. Aiken: Head, neck, jugulum, and entire upper parts clear ash; the back with a bluish tinge; the lores, quills, and tail-feathers darker; middle and secondary wing-coverts rather broadly tipped with white, forming two conspicuous bands. Lower part of the breast, abdomen, and crissum pure white, the anterior outline against the ash of the jugulum convex; sides tinged with ash. Three lateral tail-feathers entirely white, the third, however, with a narrow streak of dusky on the terminal third of the outer web; the next feather mostly plumbeous, with the basal fourth of the outer web, and the terminal half of the inner, along the shaft, white. Wing, 3.40; tail, 3.20; culmen, .50; depth of bill at base, .30; tarsus, .80.

Hab. El Paso County, Colorado.

At first sight, this bird appears to be a very distinct species, being larger than any other North American form, and possessing in the white bands on the wing characters entirely peculiar. Its large size, however, we can attribute to its alpine habitat, agreeing in this respect, as compared with J. hyemalis, with the J. alticola of Guatemala, which we can only consider an alpine or somewhat local form of J. cinereus. That the white bands on the wing do not constitute a character sufficiently important to be considered of specific value is proved by the fact that in many specimens of J. oregonus, and occasionally in J. hyemalis, there is sometimes quite a distinct tendency to these bands in the form of obscure white tips to the coverts.

Habits. But little is known as to the habits of this variety; probably they do not differ from those of its congeners. It was met with by Mr. C. E. Aiken, near Fountain, El Paso County, in Colorado Territory, in the winter of 1871-72. They were rare in the early winter, became rather common during the latter part of February and the first of March, and had all disappeared by the first of April. During winter only males were seen, but, in the spring, the females were the most numerous. They were usually seen singly, or in companies of two or three, and not, like the others, in larger flocks.

Junco oregonus, SclaterOREGON SNOWBIRDFringilla oregona, Townsend, J. A. N. Sc. VII, 1837, 188.—Ib. Narrative, 1839, 345.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 68, pl. cccxcviii. Struthus oregonus, Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 475.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route; Rep. P. R. R. VI, iv, 1857, 88. Niphœa oregona, Aud. Syn. 1839, 107.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 91, pl. clxviii.—Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 134. Junco oregonus, Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1857, 7.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 466.—Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 120 (British Columbia).—Cooper & Suckley, 202.—Coues, Pr. Phil. Ac. 1866, 85 (Arizona).—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Ch. Ac. I, 1869, 284.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 199. Fringilla hudsonia, Licht. Beit. Faun. Cal. in Abh. Akad. Wiss. Berlin, for 1838, 1839, 424 (not F. hudsonia, Forster). “Fringilla atrata, Brandt, Icon. Rosso-As. tab. ii, f. 8” (Cab.).

Sp. Char. Head and neck all round sooty-black; this color extending to the upper part of the breast, but not along the sides under the wings, and with convex outline behind. Interscapular region of the back and exposed surface of the wing-coverts and secondaries dark rufous-brown, forming a square patch. A lighter, more pinkish tint of the same on the sides of breast and belly. Rest of under parts clear white. Rump brownish-ash. Upper tail-coverts dusky. Outer two tail-feathers white; the third with only an obscure streak of white. Bill flesh-color, dusky at tip. Legs flesh-color. Length about 6.50 inches; wing, 3.00.

Hab. Pacific coast of the United States to the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, and north to Alaska. Stragglers as far east as Fort Leavenworth in winter and Great Bend of Missouri.

Sitka and Oregon specimens have the back of a darker rufous than those from California and the Middle Province, in which this portion of the body, as well as the sides, is paler, and in more abrupt contrast with the head.

Immature and the majority of winter specimens do not have the black of the head and neck so well defined, but edged above more or less with the color of the back, below with light ashy.

The Oregon Snowbird in full plumage is readily distinguishable from the eastern species by the purer white of the belly; the more sharply defined outline of the black of the head passes directly across the upper part of the breast, and is even convex in its posterior outline, without extending down the side of the breast, with its posterior outline strongly concave, as in hyemalis. The absence of black or ashy-brown under the wings, with the rufous tinge, are highly characteristic of oregonus. The head and neck are considerably blacker; the rufous of the back and wings does not exist in the other. The wings and quills are more pointed; the second quill usually longest, instead of the third, etc. The dusky of the throat reaches in J. oregonus only to the upper part of the breast; to its middle region in hyemalis.

Sometimes, in adult males, the middle and greater wing-coverts are faintly tipped with white, indicating two inconspicuous bands.

In a large series of Juncos collected at Fort Whipple, Arizona, by Dr. Coues, are several specimens so decidedly intermediate between J. oregonus and J. caniceps as to suggest the probability of their being hybrids; others, from Fort Burgwyn and Fort Bridger, are exactly like them. With the ashy head and jugulum, and black lores, as well as bright rufous back, of the latter, the sides are pinkish as in the former; while, as in this too, the posterior outline of the ash on jugulum is convex, not concave, and the rufous of the back has a tendency to tinge the wings, instead of being confined to the interscapulars. (See foot-note to synoptical table, p. 579.)

Habits. Dr. Suckley found this bird extremely abundant in Oregon and Washington Territory, where it holds about the same position that the hyemalis does in the Eastern States. Dr. Cooper states it to be a very common bird in Washington Territory, especially in the winter, when it comes about the houses and farms with precisely the same habits as the common Atlantic species. In the summer it is seen about Puget Sound, in which neighborhood it breeds. He met with young fledglings as early as May 24. At that season they were not gregarious, and were found principally about the edges of woods.

Mr. Ridgway also regards the western Snowbird as, in all appreciable respects, an exact counterpart of the eastern hyemalis. In summer he found it inhabiting the pine woods of the mountains, but in winter descending to the lowlands, and entering the towns and gardens in the same manner with the eastern species.

Dr. Cooper states this species to be numerous in winter in nearly every part of California. In the summer it resides among the mountains down to the 32d parallel. On the coast he has not determined its residence farther south than Monterey. The coolness of that locality, and its extensive forests of pines extending to the coast, favor the residence of such birds during the summer. At San Diego he observed them until the first of April, when they retired to the neighboring mountains. A few also were found in the Colorado Valley in the winter. On the Coast Mountains south of Santa Clara he found them breeding in large numbers in May, 1864. One nest contained young, just ready to fly, as early as May 13. This was built in a cavity among the roots of a large tree on a steep bank. It was made of leaves, grasses, and fine root-fibres. On the outside it was covered with an abundant coating of green moss, raised above the surface of the ground. The old birds betrayed the presence of the nest by their extreme anxiety. On the 20th he found another nest on the very summit of the mountains, supposed to be a second laying, as it contained but three eggs. It was slightly sunk in the ground under a fern, and formed like the other, but with less moss around its edge. It was lined with cows’ and horses’ hair. The eggs were bluish-white, with blackish-brown spots of various sizes thickly sprinkled around the larger end, and measuring .74 by .60 of an inch.

The only song Dr. Cooper noticed, of this species, was a faint trill much like that of the Spizella socialis, delivered from the top of some low tree in March and April. At other times they have only a sharp call-note, by which they are distinguishable from other Sparrows. While some migrate far to the south in winter, others remain as far north as the Columbia River, frequenting, in large numbers, the vicinity of barns and houses, especially when the snow is on the ground. They raise two broods in a season.

Dr. Coues found this species a very common winter resident in Arizona, arriving at Fort Whipple about October 10, soon becoming very abundant, and continuing so until the second week in April. Stragglers were seen until May 10.

Dr. Woodhouse also observed numbers of the western Snowbird on the San Francisco Mountains, in the month of October, where they were very abundant. Many specimens were obtained in Sitka by Mr. Bischoff. None have so far been recorded from the Aleutian Islands.

Dr. Kennerly frequently saw these birds near the Pueblo of Zuñi in New Mexico; in the months of October and November they were very abundant among the cedars to the westward of that settlement as far as the Little Colorado. Dr. Heermann also met with them near Fort Yuma in December, having previously noticed them during the fall, migrating in large flocks.

Mr. Aiken frequently found this species throughout the winter in Colorado. It was very common during March and the first of April. By May only a few straggling females were seen, and then they all disappeared.

The nests of this species have a general resemblance in structure to those of the common hyemalis. They are well constructed and remarkably symmetrical, made externally of mosses and other coarse materials, within which is very nicely woven an inner nest of fine, bent stems of grasses, lined with hair. The eggs, four or five in number, resemble those of the hyemalis, but are lighter. They have a ground-color of greenish-white, marked about the larger end with fine dots of reddish-brown. Their measurement is .75 by .60 of an inch.

Junco caniceps, BairdRED-BACKED SNOWBIRDStruthus caniceps, Woodhouse, Pr. A. N. Sc. Phila. VI, Dec. 1852, 202 (New Mexico and Texas).—Ib. Sitgreaves’s Report Zuñi & Colorado, 1853, 83, pl. iii. Junco caniceps, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 468, pl. lxxii, f. 1.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 201.

Sp. Char. Bill yellowish; black at the tip. Above ashy (of the same shade before and behind); the head and neck all round of this color, which extends (paling a little) along the sides, leaving the middle of the belly and crissum quite abruptly white. Lores conspicuously but not very abruptly darker. Interscapular region abruptly reddish chestnut-brown, which does not extend on the wings, and makes a triangular patch. Two outer tail-feathers entirely white; third with a long white terminal stripe on the inner web. Young streaked with blackish above and below, except along middle of belly and behind. Length, 6.00; wing, 3.23; tail, 3.04.