полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Hab. Middle Province of United States, north to beyond 40° (resident).

Poospiza belli var. belli

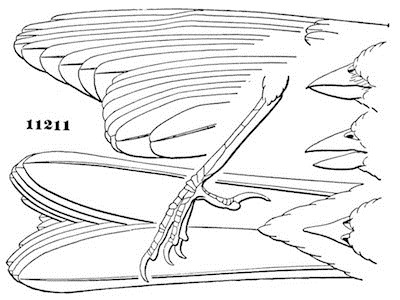

11211

The difference in size between the race of the Great Basin and that of the southern Pacific Province, of this species, is quite remarkable, being much greater than in any other instance within our knowledge. This may, perhaps, be explained by the fact that the former is not migratory, but resident even in the most northern part of its range; while the California one is also resident, and an inhabitant of only the southern portion of the coast region, not reaching nearly so far north as the race of the interior.

The coloration of the two races is quite identical, though in all specimens of var. belli the dorsal streaks are obsolete, sometimes even apparently wanting, while in the var. nevadensis they are always conspicuous. The former appears to be more brownish above than the latter.

Habits. These birds, Mr. Ridgway states, have a very general distribution, extending as far west as the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada. At Carson City, February 27, he heard for the first time their sweet sad chant. A week later he found the sage-brush full of these birds, the males being in full song and answering one another from all directions. In walking through the sage-brush these Sparrows were seen on every side, some running upon the ground with their tails elevated, uttering a chipping twitter, as they sought to conceal themselves behind the shrubs. Some were seen to alight upon the tops of dead stalks, where they sit with their tails expanded almost precisely after the manner of the Kingbird. The song of this bird is feeble, but is unsurpassed for sweetness and sadness of tone. While its effect is very like the song of a Meadow Lark singing afar off, there is, besides its peculiar sadness, something quite unique in its modulation and delivery. It is a chant, in style somewhat like the spring warbling of the Shore Lark.

On the 24th of March, at Carson City, he found these Sparrows very abundant and everywhere the predominating species, as it was also the most unsuspicious and familiar. It was even difficult to keep them from under the feet. A pair would often run before him for a distance of several rods with their unexpanded tails elevated, and when too nearly approached would only dodge in among the bushes instead of flying off.

On the 9th of April, walking among the sage-brush near Carson City, Mr. Ridgway found several nests of this Sparrow, the female parent in each instance betraying the position of her nest by running out, as he approached, from the bush beneath which it was concealed. With elevated tail, running rapidly and silently away, they disappeared among the shrubbery. In such cases a careful examination of the spot was sure to result in finding an artfully concealed nest, either embedded in the ground or a few inches above it in the lower branches of the bush. He did not find this species east of the northern end of Great Salt Lake, nor was it seen in the neighborhood of Salt Lake City, where the other species was so abundant.

The eggs of this species differ very essentially from those of the P. bilineata. They are oblong in shape, have a light greenish ground, marked all over the egg with very fine dots of a reddish-brown, and around the larger end with a ring of confluent blotches of dark purple and lines of a darker brown, almost black. They measure .80 by .60 of an inch. They resemble very closely a not uncommon variety of the eggs of the Spizella pusilla.

1

We are indebted to Professor Theodore N. Gill for the present account of the characteristics of the class of Birds as distinguished from other vertebrates, pages XI-XV.

2

Dr. Coues, in his “Key to North American Birds,” gives an able and extended article on the general characteristics of birds, and on their internal and external anatomy, to which we refer our readers. A paper by Professor E. S. Morse in the “Annals of the New York Lyceum of Natural History” (X, 1869), “On the Carpus and Tarsus of Birds,” is of much scientific value.

3

Carus and Gerstaecker (Handbuch der Zoologie, 1868, 191) present the following definition of birds as a class:—

Aves. Skin covered wholly or in part with feathers. Anterior pair of limbs, converted into wings, generally used in flight; sometimes rudimentary. Occiput with a single condyle. Jaws encased in horny sheaths, which form a bill; lower jaw of several elements and articulated behind with a distinct quadrate bone attached to the skull. Heart with double auricle and double ventricle. Air-spaces connected to a greater or less extent with the lungs; the skeleton more or less pneumatic. Diaphragm incomplete. Pelvis generally open. Reproduction by eggs, fertilized within the body, and hatched externally, either by incubation or by solar heat; the shells calcareous and hard.

4

Methodi naturalis avium disponendarum tentamen. Stockholm, 1872-73.

5

This group is insusceptible of definition. The wading birds, as usually allocated, do not possess in common one single character not also to be found in other groups, nor is the collocation of their characters peculiar.

6

Corresponding closely with the Linnæan and earlier Sundevallian acceptation of the term. Equivalent to the later Oscines of Sundevall.

7

As remarked by Sundevall, exceptions to the diagnostic pertinence of these two characters of hind claw and wing-coverts taken together are scarcely found. For, in those non-passerine birds, as Raptores and some Herodiones, in which the claw is enlarged, the wing-coverts are otherwise disposed; and similarly when, as in many Pici and elsewhere, the coverts are of a passerine character, the feet are highly diverse.

8

Laminiplantares of Sundevall plus Alaudidæ.

9

Scutelliplantares of Sundevall minus Alaudidæ.

10

Nearly equivalent to the Linnæan Picæ. Equal to the late (1873) Volucres of Sundevall.

11

A polymorphic group, perfectly distinguished from Passeres by the above characters in which, for the most part, it approximates to one or another of the following lower groups, from which, severally, it is distinguished by the inapplicability of the characters noted beyond. My divisions of Picariæ correspond respectively to the Cypselomorphæ, Coccygomorphæ, and Celeomorphæ of Huxley, from whom many of the characters are borrowed.

12

Groups G., H., and I. are respectively equal to the Charadriomorphæ, Pelargomorphæ, and Geranomorphæ of Huxley.

13

In the true conirostral or fringilliform genera the under mandible has high strong tomia, bent at an angle near the base; the corresponding portion of the upper mandible is deep, so that the nostrils are nearer the culmen than the tomia. The whole bill is more or less bent in its axis from the axis of the cranial base, so that the palate curves down, or is excavated or, as it were, is broken into two planes meeting at an angle,—one plane the anterior hard imperforate roof of the mouth, the other the back palate where the internal nares are situate (Sundevall). The single North American genus of Tanagridæ (Pyranga) is here conventionally ranged on account of its high nostrils and conic bill, although it does not show angulation of the tomia. The Icteridæ, with obviously angulated tomia, shade into the Fringillidæ in shortness and thickness of bill, and into other families in its length and slenderness.

14

These two genera, Psilorhinus and Gymnokitta, of the family Corvidæ, have naked nostrils, as under dd, but otherwise show the characters of Corvidæ.

15

With the Paridæ the authors of this work include the Nuthatches as a subfamily Sittinæ, which I prefer to dissociate and place as a group of equal grade next to Certhiidæ.

16

In the genus Ampelis and part of the Vireonidæ it is so extremely short as to appear absent, and is displaced, lying concealed outside the second (apparently first) primary, like one of the primary coverts; however, it may always be detected on close examination, differing from the coverts with which it is associated in some points of size and shape, if not also of color.

17

In Ampelis there is tendency to subdivision of the lateral plates; in Myiadestes the anterior scutella are obsolete.

18

Excepting Picoides, in which the true hind toe (hallux) is wanting; the outer or fourth toe being, however, reversed as usual, and taking the place of the hind toe.

19

Excepting Sphyrapicus, in which the tongue is not more protrusible than in ordinary birds.

20

Our species falls rather in a restricted family Aridæ, as distinguished from Psittacidæ proper.

21

In a perfectly fresh specimen of Turdus mustelinus, the basal half of the first phalanx of the inner toe is connected with the first joint of the middle toe by a membrane which stretches across to within two fifths of the end of the latter; there appears, however, to be no ligamentous adhesion. The basal joint of the outer toe is entirely adherent, and a membrane extends from nearly the basal half of the second joint to the distal end of the first joint of the middle toe. When this connecting membrane becomes dried the division of the toes appears considerably greater.

When the toes are all extended in line with the tarsus, the hind claw stretches a little beyond the lateral and scarcely reaches the base of the middle claw.

The plates at the upper surface of the basal joints of the toes are quadrangular and opposite each other.

22

See Baird, Review American Birds, I, 1864, 7, 8.

23

Harporhynchus ocellatus, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1862, p. 18, pl. iii.

24

C. ardesiacus, Salvin, Ibis, N. S. III, 121, pl. ii.

25

C. pallasi, Temm. Man. d’Orn. I, p. 177.—Salvin, Ibis, III, 1867, 119. (Sturnus cinclus, var. Pallas, Zoögr. R.-As. I, 426.)

26

S. azurea, Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1864, 62. (S. azurea, Swainson.)

27

Parus meridionalis, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1856, 293.—Baird, Rev. 81.

28

Parus sibiricus, Gmel. S. N. 1788, p. 1013.

29

This remark applies to the Mexican race.

30

N. rufa, Baird. (Alauda rufa, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 798.)

31

P. bogotensis, Baird. (Anthus bogotensis, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1855, 109, pl. ci.)

32

Anthus (Notiocorys) rufus, Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1864, 156 (Alauda rufa, Gm.). Hab. Isthmus of Panama.

33

Anthus (Pediocorys) bogotensis, Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1864, 157 (Anthus bogotensis, Sclater). Hab. Ecuador, Colombia.

34

Sylvia pitiayumi, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. II, 1816, 276. Parula pit. Sclat. Catal. 26, no. 165.—Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, I, 1865, 170.

35

Parula insularis, Lawr. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. X, Feb. 1871.

36

Parula inornata, Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, I, 1865, 171.

37

Or if with white markings, the prevailing color yellow, as in D. pinus, in which only the adult ♂ has the wing-bands ashy-white.

38

The wing-formula, though varying among individuals, is nevertheless in a measure characteristic. An average specimen is in each case chosen.

39

D. gundlachi, Baird, Review Am. B. I , 1865, 197.

40

Dendroica petechia, Baird, Review, 199. (Motacilla petechia, Linn. 1766.)

A specimen from Port au Prince is smaller, measuring, wing, 2.50; tail, 2.10; bill, .31; tarsus, .74. It is perhaps lighter green above than Jamaican specimens. These features may only be characteristic of the particular individual.

41

D. ruficapilla, Baird, Rev. 201.

A single specimen from Porto Rico differs in some respects from the average of a series from the other islands named. The chief differences are, less thickly streaked throat, and distinct shaft-streaks of dark chestnut on the back. However, one or two specimens of true ruficapilla from St. Thomas have the upper part of the throat streaked, and one of them has the streaks on the back. In all probability other specimens from Porto Rico would be more like typical species of this race as seen in the majority of those from St. Thomas and St. Bartholomew.

42

D. aureola, Baird, Rev. 194. (Sylvicola a. Gould, Voyage Beagle, 1841, 86.)

43

D. capitalis, Lawr. Pr. Phila. Acad. 1868, 359. Barbadoes. Dendroica, Baird, Rev. 201.

44

D. vieilloti, Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. May, 1860, 192. (Panama, Carthagena.)—Baird, Rev. 203.

45

D. rufigula, Baird, Rev. p. 204. The habitat as Martinique, W. I., was there queried, but without any reason for so doing other than that this was the locality of Vieillot’s species, with which the type described in Review nearly agreed. Should Vieillot’s species be really from Martinique, in all probability the present bird will be found to be different, and therefore not entitled to the name here given. Provided such is the case, the name “ruficeps,” Cabanis, cannot with propriety be used, as under that head he includes specimens from Carthagena (true vieilloti), Costa Rica, and Mexico (the latter bryanti).

46

D. vieilloti, var. bryanti, Ridgway.

47

Sylvicola eoa, Gosse, Birds of Jamaica, 1847, 158; Illustrations Birds Jam. Dendroica eoa, Baird, Rev. 195. The true position of this species is very uncertain, owing to the imperfect description, or rather the incomplete plumage, of the types. There is no doubt, however, that it is entirely different from any other, and in its having, as expressly stated, the inner webs yellow, thus bringing it into close relation with the “Golden Warblers.”

48

D. pharetra, Baird, Rev. 192. (Sylvicola pharetra, Gosse, Birds Jam. 1847, 163.)

49

D. adelaidæ, Baird, Rev. April, 1865, 212.

50

D. pityophila, Baird, Rev. 208. (Sylvicola p. Gundl. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. Oct. 1855, 160.)

51

Dendroica adelaidæ, Baird, Rev. 1865, 212. Hab. Porto Rico.

52

Geothlypis rostratus, Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. N. H. March, 1867, 67, Inagua.

53

Geothlypis melanops, Baird, Review Am. Birds, I, April, 1865, p. 222.

54

Geothlypis æquinoctialis (Cabanis), Baird, Rev. I, p. 224. (Motacilla æq. Gmelin, S. N. I, 1788, 972.)

55

Geothlypis velata (Cabanis), Baird, Rev. I, 223. (Sylvia vel. Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 22, pl. lxxiv.)

56

Geothlypis poliocephala, Baird, Review Am. Birds, I, April, 1865, p. 225.

57

Geothlypis poliocephala, var. caninucha, Ridgway.

The G. speciosa, Scl. (P. Z. 1858, 447; and Baird, Rev. 1864, p. 223), from Mexico, and G. semiflavus, Scl. (P. Z. S. 1860, 273, 291.—Baird, Rev. I, 1864, 223), from Ecuador, are species allied to G. trichas, and possibly referable to it. The original descriptions afford no tangible distinctive characters. It is barely possible, however, that they are distinct.

58

Granatellus, Dubus. Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1865, 230. (Type, G. venustus, Dubus.)

59

Genera Myioborus, Euthlypis, Myiothlypis, Basileuterus, Idiotes, and Ergaticus. All Middle and South America.

60

Setophaga picta (Swainson), Baird, Rev. 1865, 256. Muscicapa leucomus, Giraud, Texas Birds. Hab. Mexico and Guatemala.

61

Setophaga miniata (Swainson), Baird, Rev. 1865, 256. Muscicapa derhami, Giraud, Texas Birds. Hab. Mexico.

62

Hirundo (Callichelidon) cyaneoviridis (Bryant), Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1865, 303. Bahamas. This species may yet be detected on the Florida coast.

63

Progne subis, var. concolor. Hirundo concolor, Gould, P. Z. S. 1837, 22 (James I., Galapagos). Progne c. Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 278. Progne modesta, Gould, Birds Beagle, 39, pl. v. (Same specimen.)

64

Progne subis, var. furcata. Progne furcata, Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 278. (Chile.)

65

Progne subis, var. elegans. Progne elegans, Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 275. (Vermejo River. ? Progne purpurea, Darwin, B. Beagle 38 (Montevideo, November), Bahia Blanca, Buenos Ayres, September.)

66

Progne (subis var?) dominicensis. Hirundo dominicensis, Gm. S. N. I, 1788, 1025. Progne d. March, P. A. N. S. 1863, 295; Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 279.

67

Progne (subis var?) domestica. Progne domestica (Vieill.) Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 282. (Paraguay and Bolivia.) (Hirundo domestica, Vieill. Nouv. Dict, xiv, 1817, 521.)

68

Progne, (subis var?) leucogaster. Progne leucogaster, Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1865, 280. (Southern Mexico to Carthagena.) Progne dominicensis and P. chalybea, Auch. (nec Gmel.).

From a careful examination of specimens of the above forms, the opinion that they are all local differentiations of one primitive type at once presents itself. The differences from the typical subis are not great, except in the white-bellied group (dominicensis and its allies), while an approach to the white belly of these is plainly to be seen in P. cryptoleuca; again, some specimens of dominicensis have the crissum mixed with blackish, while others have it wholly snowy-white. While the male of cryptoleuca is scarcely distinguishable, at first sight, from that of subis, the female is entirely different, but, on the other hand, scarcely to be distinguished from that of dominicensis and leucogaster. Adult males of the latter species are much like adult females of dominicensis, while Floridan (resident) specimens of subis approach very decidedly to the rather unique characters of elegans. It is therefore extremely probable that all are merely local modifications of one species.

69

C. cyaneoviridis, Bryant; Baird, Rev. 303 (Bahamas).

70

Vireosylvia calidris, Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1865, 329. (Motacilla calidris, L. Syst. Nat. 10th ed. 1758, 184.)

71

V. calidris var. barbadense, Ridgway.

72

V. olivacea var. chivi. Vireosylvia chivi, Baird, Rev. 327. (Sylvia chivi, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. XI, 1817, 174.)

73

V. flavoviridis var. agilis. Vireosylvia agilis, Baird, Rev. 338. (Lanius agilis, Licht. Verz. Doubl., 1823, No. 526.)

74

V. magister, Baird.

75

V. gilva var. josephæ. Vireosylvia josephæ, Baird, Rev. 1865, 344 (Vireo josephæ, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1859, 137, pl. cliv). Comparing typical examples of this “species” with those of gilvus from North America, they appear very widely different indeed, so far as coloration is concerned, though nearly identical in form. But a specimen from an intermediate locality (54,262, Orizaba, Mexico, F. Sumichrast) combines so perfectly all the characters of the two, that it would be impossible to refer it to one or the other as distinct species. It therefore becomes necessary to assume that the V. josephæ is a permanently resident tropical race of a species of which V. gilvus is the northern representative; which theory is strengthened by the fact that of the latter there are no specimens found south of the United States, indicating that in winter it does not pass beyond their limit, or at least not far to the southward.

76

The Jamaican bird is V. calidris, not barbatulus. In all probability, however, they do not differ in habits and notes.—R. R.

77

Vireosylvia propinqua, Baird, Rev. 1865, p. 348. This appears to be merely a permanent resident race of solitarius, which itself visits Guatemala only in winter. Closely resembling the latter, it differs essentially in the respects pointed out above. The difference in coloration is produced by a shifting, as it were, toward the head of the yellow and olive, leaving the upper tail-coverts clear ash, and the lower pure white, and encroaching upon the ash anteriorly to the crown and ear-coverts, and the white alongside of the throat. In the V. plumbeus these tints are simply almost entirely removed, leaving clear ash and pure white, with a tinge, however, of olive on the rump and of yellow on the sides. In V. cassini the tints are darkened and browned by the peculiar influence of the region where found, there being neither clear ash, nor olive-green, nor pure yellow or white, in the plumage.

78

Vireo carmioli, Baird, Review Am. B. I , 1865, p. 356. Hab. Costa Rica.

79

Bombycilla phœnicopterum, Temm. Pl. Col. II, 1838; pl. 450. The A. phœnicopterum is stated by Temminck to have the nasal setæ so short as to leave the nostrils exposed, and to lack the sealing-wax appendages; the latter condition may, however, result from the immaturity of the specimen, as it is very common to find the same thing in individuals of the other species.

80

Myiadestes obscurus (Lafres.), Baird, Rev. Am. Birds, 1866, 430. Hab. Mountains of Mexico to Guatemala and Tres Marias Islands.