полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

These birds do not come down near the sea-coast even at the mouth of the Columbia, and in California have not been met with in the Coast Range. They are said to feed chiefly on the seeds of the pine, spruce, and cottonwood trees, occasionally seeking other seeds near the ground. They are silent when feeding, but utter a loud call-note as they fly from place to place. In spring, Dr. Cooper states, they have a short but melodious song, resembling that of the Robin or Black-headed Grosbeak. He afterwards met with a flock in the winter near Santa Cruz, where they remained until the end of April. Their favorite resort was a small grove of alders and willows, close to the town, where their loud call-notes could be heard at all times of the day, though he never heard them sing. In the early spring their favorite food was the young leaves of various wild plants that grew under the trees. They also fed on the buds of the Negundo, and frequented the large pear-trees in the old mission garden. They were very tame, and allowed an approach to within a few yards, when feeding. Mr. Townsend, in 1836, found this Grosbeak abundant about the Columbia River. Late in May they were quite numerous in the pine woods. They were very unsuspicious and tame. Under the impression that these birds were only musical towards night, they have been styled the Evening Grosbeak. But this, according to Mr. Townsend, is a misnomer. He also contraverts several other statements made in reference to their habits. He found them remarkably noisy from morning until night, when they quietly retire like other birds, and are not heard from until the next day-dawn. They go in large flocks, and are rarely met with singly. As they feed upon the seeds of the pine and other trees, they proceed by a succession of hops to the extremities of the branches. They also feed largely on the larvæ of the large black ant, for which object they frequent the tops of the low oaks on the edges of the forests. Their ordinary voice is said to be a single screaming note, uttered while feeding. At times, about midday, the male attempts a song, which Mr. Townsend describes as a miserable failure. It is a single note, a warbling call like the first note of the Robin, but not so sweet, and suddenly checked, as if the performer were out of breath.

Mr. Sumichrast met with the variety of this species designated as montana, May, 1857, in the pine woods of Monte Alto, about twelve leagues from Mexico; and although he has never found it in the alpine region of Vera Cruz, he thinks it probable it will be found to be a resident of that district.

Lake Superior has been stated to be its most eastern point of occurrence, but, though this may be true as a general rule, several instances of the accidental appearance of this nomadic species much farther to the east are known. On February 14, 1871, Mr. Kumlien, while out in the woods with his son, saw a small flock of these birds in Dane County, Wisconsin. There were six of them, but, having no gun, he did not procure any. Later in the season he again met with and secured specimens. In the following March, Dr. Hoy of Racine also obtained several near that city. He also informs me that during the winter of 1870-71 there were large flocks of these birds near Freeport, Ill. One person procured twenty-four specimens. One season he noticed them as late as May. They frequent the maple woods, and feed on the seeds fallen on the ground. They also eat the buds of the wild cherry. Their visits are made at irregular intervals. In some years not a single individual can be seen, while in others they make their appearance in December and continue through the whole winter.

Specimens have also been obtained near Cleveland, Ohio, and at Hamilton, Canada; and Mr. Thomas McIlwraith states that Mr. T. J. Cottle of Woodstock, Ontario, shot several of these birds in his orchard in the month of May. They were quite numerous, and remained about the place several days.

Genus PINICOLA, VieillPinicola, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. I, 1807, 4, pl. i, f. 13.

“ Strobilophaga, Vieillot, Analyse, 1816.”

“ Corythus, Cuvier, R. An. 1817.”

Char. Bill short, nearly as high as long; upper outline much curved from the base; the margins of the mandibles rounded; the commissure gently concave, and abruptly deflexed at the tip; base of the upper mandible much concealed by the bristly feathers covering the basal third. Tarsus rather shorter than the middle toe; lateral toes short, but their long claws reach the base of the middle one, which is longer than the hind claw. Wings moderate; the first quill rather shorter than the second, third, and fourth. Tail rather shorter than the wings; nearly even.

Of this genus one species is found in northern America, and is now considered as identical with that belonging to the northern regions of the Old World.

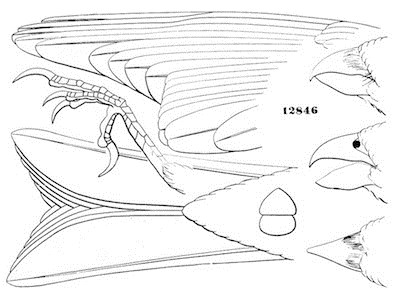

PLATE XXI.

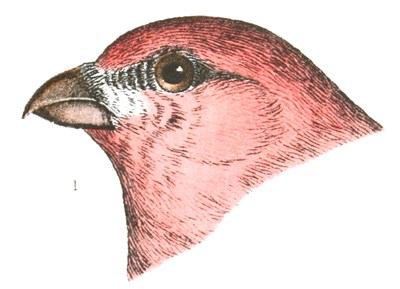

1. Pinicola enucleator. ♂ N. Y., 12846.

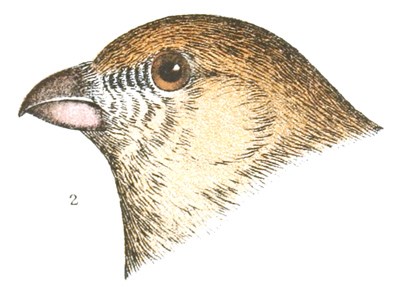

2. Pinicola enucleator. ♀.

3. Carpodacus frontalis., var. frontalis. ♂ Cal., 10223.

4. Carpodacus cassini. ♂ Rocky Mts., 53471.

5. Carpodacus cassini. ♀ Cal., 18027.

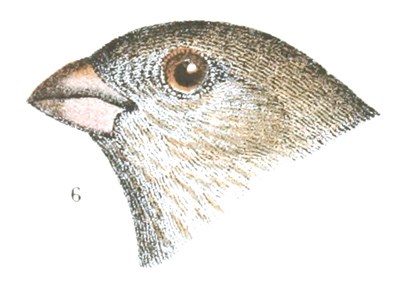

6. Carpodacus frontalis, var. frontalis. ♀ Cal., 6429.

7. Carpodacus purpureus. ♂ Pa., 796.

8. Carpodacus purpureus. ♀ Pa., 2139.

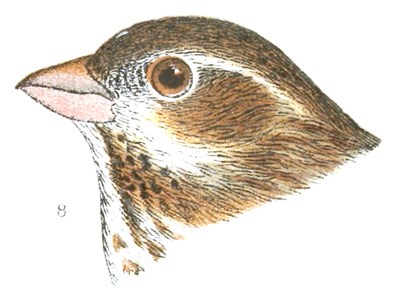

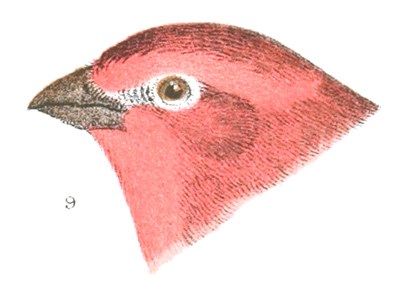

9. Carpodacus frontalis, var. rhodocolpus. ♂ Cal.

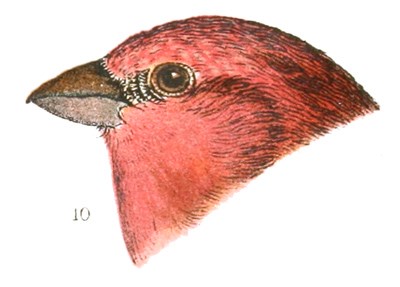

10. Carpodacus var. californicus. ♂ Cal., 10230.

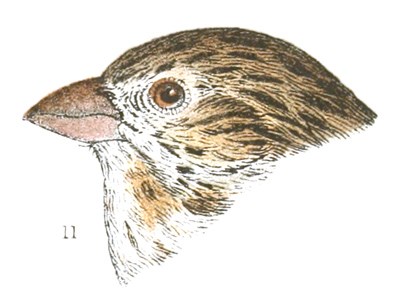

11. Carpodacus var. californicus. ♀ Cal., 10231.

12. Carpodacus frontalis, var. hæmorrhous. ♂ Mex.

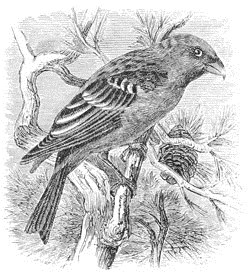

Pinicola enucleator, CabanisTHE PINE GROSBEAK

Coccothraustes canadensis, Brisson, Orn. III, 1760, 250, pl. xii, f. 3. “Corythus canadensis, Brehm, Vögel Deutschlands” (1831?). Pinicola canadensis, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 167.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 410.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chic. Ac. Sc. I, 1869, 281 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 151.—Samuels, Birds N. Eng. 283. Pinicola americana (Cab. MSS.), Bp. Consp. 1850, 528. Loxia enucleator, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 299.—Forst. Phil. Trans. LXII, 1772, 383.—Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1808, 80, pl. v. Pyrrhula enucleator, Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 414, pl. ccclviii. Corythus enucleator, Bonap. List. 1838.—Aud. Syn. 127.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 179, pl. cxcix.—Bon. & Schlegel, Mon. des Loxiens, 1850, 9, pl. ix, xi, xii.—Degland & Gerbe, Orn. Europ. I, 258. Pinicola enucleator, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. I, 1851, 167.

Pinicola enucleator.

12846

Sp. Char. Bill and legs black. Male. General color light carmine-red or rose, not continuous above, however, except on the head; the feathers showing brownish centres on the back, where, too, the red is darker. Loral region, base of lower jaw all round, sides (under the wing), abdomen, and posterior part of the body, with under tail-coverts, ashy, whitest behind. Wing with two white bands across the tips of the greater and middle coverts; the outer edges of the quills also white, broadest on the tertiaries, on secondaries tinged with red. Female ashy, brownish above, tinged with greenish-yellow beneath; top of head, rump, and upper tail-coverts brownish gamboge-yellow. Wings much as in the male. Length about 8.50; wing, 4.50; tail, 4.00. Young like female, but more ashy.

Hab. Arctic America, south to United States in severe winters.

A careful comparison of American with European specimens of the Pine Grosbeak does not present any tangible point of distinction, and it appears inexpedient to preserve the name of canadensis for the bird of the New World. There is considerable difference in the size, the proportions of the bill, and the color of different specimens, but none of appreciable geographical value.

Pinicola enucleator.

A considerable number of specimens from Kodiak (perhaps to be found in other localities on the northwest coast) compared with eastern have conspicuously larger bills, almost equal to cardinalis in this respect. In No. 54,465 the length from forehead is .80; from nostril, .50; from gape, .66; gonys, .40; greatest depth, .51. In a Brooklyn skin (12,846) the same measurements are from forehead, .60; from nostril, .44; from gape, .60; gonys, .34; greatest depth, .40. A Saskatchewan skin is intermediate. A European specimen has the bill as long as that from Kodiak, but less swollen. A Himalayan species (C. subhimachalus) is much smaller, and differently colored.

These Kodiak specimens approach the European bird more nearly in form of the bill, in which there is a tendency to a more abruptly hooked upper mandible than in the birds from the eastern portions of British America. As a general thing, the red tint is brighter in American than in European birds.

Habits. The Pine Grosbeak is, to a large extent, a resident of the portions of North America north of the United States. In the northern parts of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, as well as in western America, it is found throughout the year in the dark evergreen forests. In the winter it is an irregular visitant as far south as Philadelphia, being in some seasons very abundant, and again for several winters quite rare.

Mr. Boardman mentions it as abundant, in the winter, about Calais, and Mr. Verrill gives it as quite common in the vicinity of Norway. It is found every winter more or less frequently in Eastern Massachusetts, though Mr. Allen regards it as rare in the vicinity of Springfield. It is not cited by Dr. Cooper as a bird of Washington Territory, but he mentions it as not uncommon near the summits of the Sierra Nevada, latitude 39°, in September. It probably breeds there, as he found two birds in that region in the young plumage. They were feeding on spruce seeds when he first saw them, and lingered even after their companions had been shot, and allowed him to approach within a few feet of them.

Mr. R. Brown (Ibis, 1868) states that during the winter of 1866, while snow was lying on the ground, two pairs of this species were shot at Fort Rupert, Vancouver Island.

Wilson met with occasional specimens of these birds in the vicinity of Philadelphia, generally in immature plumage, and kept one several months, to note any change in its plumage. In the summer it lost all its red colors and became of a greenish-yellow. In May and June, its song, though not so loud as that of some birds, was extremely clear, mellow, and sweet. This song it warbled out for the whole morning, and also imitated the notes of a Cardinal, that hung near it. It became exceedingly tame and familiar, and when in want of food or water, uttered a continual melancholy and anxious note.

In the winter of 1835, and for several following seasons, these birds were exceedingly abundant in the vicinity of Boston. They appeared early in December, and remained until quite late in March, feeding chiefly on the berries of the red cedar. They were so unsuspecting and familiar that it was often possible to capture them alive in butterfly-nets, and to knock them down with poles. Large numbers were destroyed and brought to market, and many were taken alive and caged. They were tame, but unhappy in confinement, uttering mournful cries as the warm weather approached. In the winter of 1869-70 they again made their appearance in extraordinary numbers, in a few localities on the sea-coast of Massachusetts, where they did considerable damage to the fruit-buds of the apple and pear.

Sir John Richardson states that this bird was not observed by his expedition higher than the 60th parallel. It lives, for the most part, a very retired life, in the deepest recesses of the pine forests, where it passes the entire year, having been found by Mr. Drage, near York Fort, on the 25th of January, 1747. Richardson adds that it builds its nest on the lower branches of trees, and feeds chiefly on the seeds of the white spruce.

Dr. Coues speaks of it as not at all rare along the coast of Labrador, where he obtained several specimens. It was confined entirely to the thick woods and patches of scrubby juniper. A female remained unconcernedly on a twig after he had shot her mate, uttering continually a low soft shep, like that of the Fox-colored Sparrow. Another note was a prolonged whirring chirrup, uttered in a rather low tone, apparently a note of recognition.

A lady resident in Newfoundland informed Mr. Audubon that she had kept several of these Grosbeaks in confinement, that they soon became very familiar, would sing during the night, feeding, during the summer, on all kinds of fruit and berries, and in the winter on different seeds. Mr. Audubon also often observed that, when firing at one of their number, the others, instead of flying away, would move towards him, often to within a few feet, and remain on the lower branches of the trees, gazing at him in curiosity, entirely unmingled with any sense of their own danger. Mr. Audubon quotes from Mr. McCulloch, of Pictou, an interesting account of the habits of one of these birds, kept in confinement. The winter had been very severe, the storms violent, and, in consequence of the depth of snow, many birds had perished from hunger and cold. The Grosbeaks, driven from the woods, sought food around the barns and outhouses, and crowded the streets of Pictou. One of these, taken in a starving condition, soon became so tame as to feed from his hand, lived at large in his chamber, and would awaken him early in the morning to receive his allowance of seed. As spring approached, he began to whistle in the morning, and his notes were exceedingly rich and full. As the time came when his mates were moving north, his familiarity entirely disappeared, and he sought constantly, by day and by night, to escape by dashing against the window-panes, and during the day filled the house with his piteous wailing cries, refusing his food, so that in pity he was let out. But no sooner was he thus released than he seemed indifferent to the privilege, and kept about the door so persistently that he had at last to be driven away, lest some accident should befall him.

The Pine Grosbeaks were found by Bischoff at Sitka and at Kodiak, and are said by Mr. Dall to be extremely common near Nulato, and wherever there are trees throughout the Yukon Territory. They frequent groves of willow and poplar, near open places, and especially the water-side in winter, and in summer seek more retired places for breeding. Their crops, when opened, were always found to contain the hearts of the buds of poplars, with the external coverings carefully rejected, and were never found to include anything else. Mr. Dall noticed no song, only a twitter and a long chirp. He found them excellent as an article of food. European eggs of this bird, taken by Mr. Wolley in Finland in 1858, are of an oblong-oval shape, and have a light slate-colored ground with a marked tinge of greenish, broadly marked and plashed with faint, subdued cloudy patches of brownish-purple, and sparingly spotted, chiefly at the larger end, with blackish-brown and dark purple. They measure 1.02 inches in length by .70 in breadth.

No positively identified eggs of the American Pine Grosbeak are as yet known in collections, but Mr. Boardman has found a nest, near Calais, about which there can be little doubt, although the parent was not seen. This was placed in an alder-bush in a wet meadow, and was about four feet from the ground. It was composed entirely of coarse green mosses. The eggs were two, and were not distinguishable from those of the European enucleator.

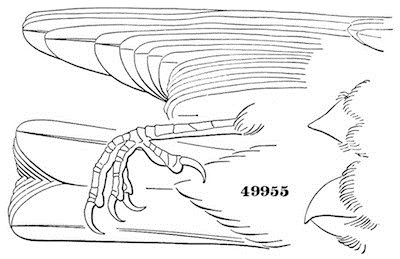

Genus PYRRHULA, PallasPyrrhula, “Brisson, Orn. 1760.” Pallas.

Gen. Char. Bill very short and thick, higher than long, swollen. Lower jaw broader at base than upper jaw, and broader than length of gonys. Nostrils and base of mandible concealed by a thick tuft of rather soft feathers. Tail nearly even, shorter than the pointed wings; upper coverts reaching over nearly two thirds the tail. Middle and hind claws about equal.

This genus is closely related to Pinicola, but has a more swollen and much shorter bill, the lower jaw disproportionately larger, and wider than long along gonys, instead of being about equal. The nasal tuft is thicker and more feathery and less bristly than in Pinicola. The upper tail-coverts are much longer, the tail less emarginate. Other differences exist in the grooves and ridges of the palate, which need not be here referred to. The middle claw is about equal to hind claw; not longer, as in Pinicola.

Pyrrhula cassini.

49955

The genus Pyrrhula is an Old World one; extending across from the Atlantic to the Pacific, six or eight species or varieties being recognized by naturalists. All have the back ash-colored; the wings and tail, with top of head, lustrous black; the under parts ash, generally with vermilion on the cheeks and chin, sometimes extending over the whole under surface; the rump and crissum white: the females similar, but lacking the vermilion. Its introduction into the North American fauna rests on the collecting by the naturalists of the Russian Telegraph Expedition in Alaska of a specimen which—if a full-plumaged male, as stated—differs from all of its congeners in the entire absence of any vermilion tint.

Pyrrhula cassini, BairdCASSIN’S BULLFINCHP. coccinea, var. cassini, Baird, Trans. Chicago, Ac. Sc. I, 1869, ii, p. 316.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chic. Ac. I, 1869, 281 (Alaska). P. cassini, Tristram, Ibis, 1871, 231.—Finsch, Ornith. N. W. Amerikas, 1872, 54.

Pyrrhula cassini.

Sp. Char. Description of specimen No. 49,955: Upper parts clear ash-gray, as are the alula, and the lesser and middle secondary and the primary wing-coverts. Under parts and the sides of head cinnamon-gray; the inside of wings and axillars, anal region, tibia, crissum, and rump white; wings and tail, including upper tail-coverts, the entire top of head (to level of eyes), the base of bill all round, and the chin, lustrous violet-black. Greater wing-coverts black, with a broad band of ashy-white across the ends; outer primaries, externally, with a narrow border of grayish-white near the ends; inner edges suffused with the same. Outer tail-feathers with an elongated patch of white in the terminal half, along the shaft, but not reaching the tip. Bill black; feet dusky.

Dimensions (prepared specimen): Total length, 6.50; wing, 3.55; tail, 3.25. Exposed portion of first primary, 2.65. Bill: Length from forehead, .44; from nostril, .34. Legs: Tarsus, .75; claw alone, .26; hind toe and claw, .45; claw alone, .25.

No. 49,955, adult male. Nulato, Yukon River, Alaska. January 10, 1867. W. H. Dall (No. 553).

The specimen referred to above is the first record of the occurrence in America of a genus heretofore considered as belonging exclusively to the Old World.

This bird was described in 1869 as a possible variety of P. coccinea of Europe. On submitting the typical specimens to Mr. H. B. Tristram of England, it was decided to be a well-marked and distinct species, as explained in the following extract from a letter received from him.

“The coloration of the back is the same as in males of P. coccinea and P. rubicilla, and differs from the coloration of the ♀ in all three species. In all the ♀ has the back brown instead of slate-colored. Your bird, however, differs from P. coccinea in having the under parts of the same color as the ♂ of P. griseiventris with a slightly redder hue on the flanks, while P. coccinea is a brilliant blazing red. In this your bird is like P. murina of the Azores, but that has no white on the rump.

“Nor can it be ♂ juv. of P. coccinea, because it has the black head, and the young assumes the black head and red breast simultaneously, or rather the red begins first. It differs from P. nipalensis in having a black head and broad white rump, as well as in size.”

Dr. O. Finsch, of Bremen, agrees with Mr. Tristram in considering it as specifically distinct, and says that the long white shaft-streak on the outermost tail-feather is to be considered as one of the peculiar characters, and that in general it resembles the female of P. griseiventris, Lafr., but differs in having the back beautiful ash-gray.

Habits. This new species of Bullfinch, having a close resemblance to the P. coccinea of Europe, was obtained by Mr. Dall, near Nulato, Alaska, January 10, 1867. An Indian brought it in alive, but badly wounded, having shot it from a small tree near the fort. He had never seen anything like it before, nor had any of the Russians. Captain Everett Smith had, however, met with several flocks of the same species near Ulukuk. This specimen was a male, with black eyes, feet, and bill, and was the only bird of the kind met with by Mr. Dall.

In size it is about equal to P. coccinea, which is now quite generally considered to be simply a large race of the common Bullfinch (P. vulgaris), and the habits of the American bird are doubtless similar to those of its congeners. The European races inhabit the mountainous regions of Northern and Central Europe, appearing in large flocks in December and January in the more southern regions. In their return in spring to their summer quarters, they move in smaller numbers. They nest in the mountain forests, on trees or bushes. Their nest is usually but a few feet from the ground, is beautifully wrought in a cup shape, made externally of small twigs, blades of grass, and rootlets, lined with coarse hair. They lay five eggs, the ground-color of which shades from a light blue to a bluish or a greenish white, with brown and violet-colored spots, that usually form a ring around the larger end. Their food is grain and small seeds, and, in spring, the buds of certain trees.

The Bullfinch is a favorite cage-bird, soon reconciled to confinement, and capable of being taught to whistle whole airs of opera music with wonderful exactness and beauty.

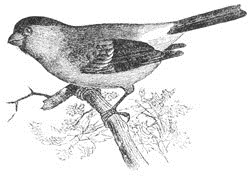

Genus CARPODACUS, KaupCarpodacus, Kaup, “Entw. Europ. Thierw. 1829.” (Type, Loxia erythrina, Pall.)