полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Wilson, in describing the nest and eggs of this species, has evidently confounded them and some of their habits with those of the Blue Grosbeak. Their eggs are not light-blue, nor are the nests, so far as I know, as described by him. Audubon and Nuttall copy substantially his errors.

The food of this species during the spring and early summer is chiefly various kinds of large coleopterous insects, bees, wasps, and others. Later in the season, when whortleberries are ripe, they feed chiefly on these and other small fruit. In taking its food it rarely alights on the ground, but prefers to capture its insects while on the wing.

The usual note of this bird, which Mr. Audubon pronounces unmusical, resembles the sounds “chicky-chucky-chuck.” The same writer states that during the spring this bird sings pleasantly for nearly half an hour in succession, that its song resembles that of the Red-eyed Vireo, and that its notes are sweeter and more varied and nearly equal to those of the Orchard Oriole.

The late Dr. Gerhardt of Varnell’s Station, in Northern Georgia, informed me that these birds are quite common in that section of country. The nest is usually built on one of the lower limbs of a post-oak, or in a pine sapling, at a height of from six to twenty feet. They are usually constructed toward the extremity of the limb, and so far from the trunk as to be very difficult of access. They are generally built from the middle to the end of May. The eggs are four in number.

In Southern Illinois, according to Mr. Ridgway, the Summer Redbird arrives about the 20th of April, staying until the last of September. It is more abundant than the Scarlet Tanager, and much less retiring in its habits, frequenting the open groves instead of the deeper woods and the forests of the bottom-lands, being especially attached to the parks and groves within the towns. From its similarity in appearance, manners, and notes to the Scarlet Tanager, it is seldom distinguished by the common people from that bird, and those who notice the difference in color between the two generally consider this the younger stage of plumage of the black-winged species. Its song is said to be somewhat after the style of the Robin, but in a firmer tone and more continued. It differs from the song of the P. rubra in being more vigorous, and delivered in a manner less faltering. Its ordinary note of anxiety when the nest is approached is a peculiar pa-chip´it-tūt-tūt-tūt, very different from the weaker chip´-al, rā-rēē of the P. rubra. The nest is placed on a low horizontal or drooping branch, near its extremity, the tree being generally an oak, or sometimes a hickory, and situated near the roadside or at the edge of a grove. In its construction it is described as very thin, though by no means frail, permitting the eggs to be seen through the interstices from below. Mr. Ridgway never found more than three eggs in one nest.

A nest of this species (Smith. Coll., 589) from Prairie Mer Rouge, Louisiana, has a diameter of four inches and a height of two. Like all the nests of this family, the cavity is very shallow, its deepest depression being hardly half an inch. So far from corresponding with the descriptions generally given of it, this nest is well and even strongly put together, although a portion of the base and some of the external parts are somewhat openly interwoven, as if for ventilation. These materials are fragments of plants, catkins, leaves, stems, and grasses. These seem to constitute a distinct part of the nest, and are of unequal thicknesses in different parts of the structure. Within this external frame is a much more artistic and elaborately interwoven basket, composed entirely of fine, slender, and dry grasses, homogeneous in character, and evidently gathered just at the time its seed was ripening. It is of a bright straw-yellow, and forms the whole internal portion of the nest.

The eggs vary somewhat in size and shape, from an oblong to a rounded oval. Their length is from .80 of an inch to an inch, and their breadth averages .68. Their color is a bright light shade of emerald-green, spotted, marbled, dotted, and blotched with various shades of lilac, brownish-purple, and dark-brown. These are generally well diffused equally over the entire egg.

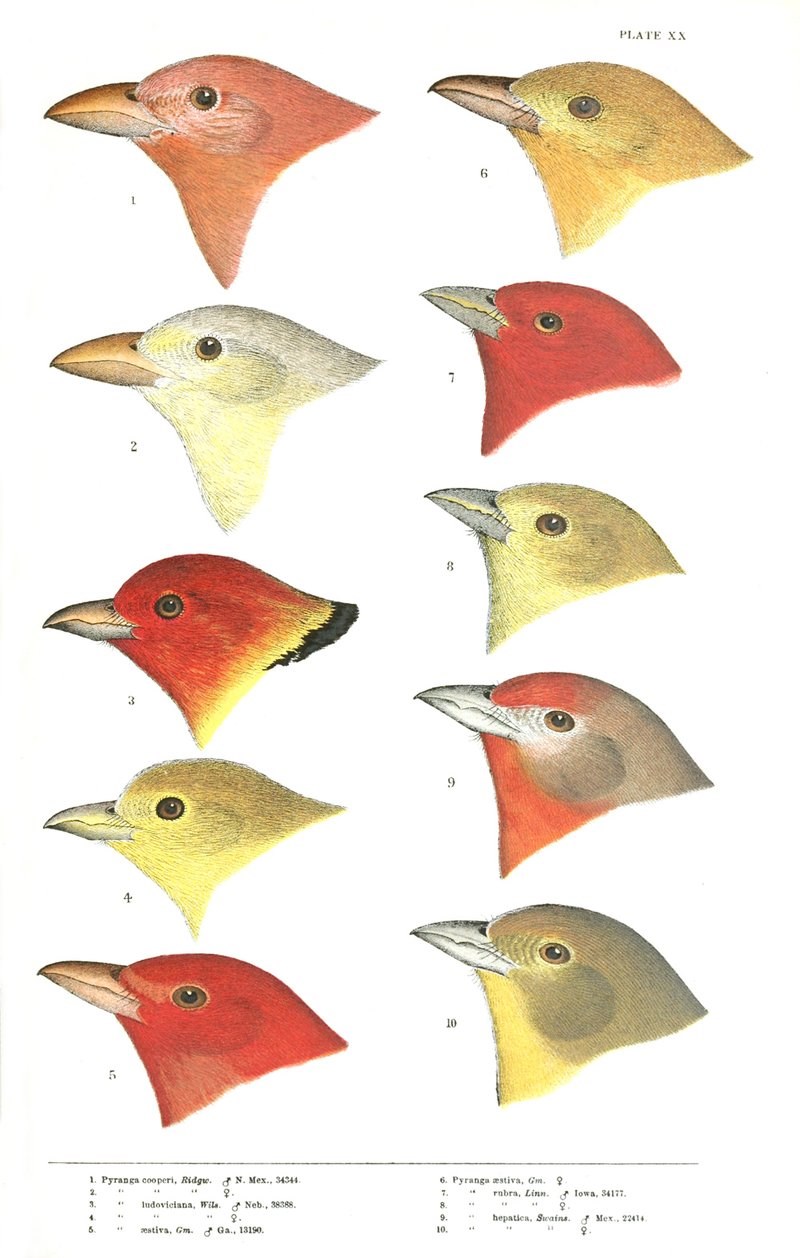

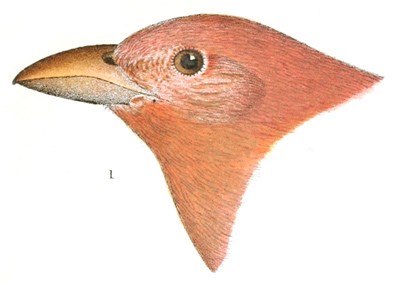

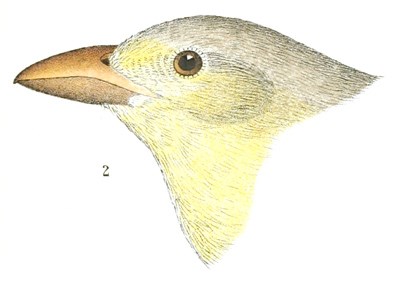

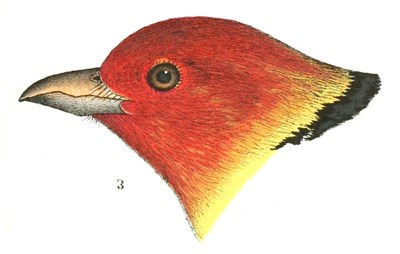

PLATE XX.

1. Pyranga cooperi, Ridgw. ♂ N. Mex., 34344.

2. Pyranga cooperi, Ridgw. ♀.

3. Pyranga ludoviciana, Wils. Neb., 38388.

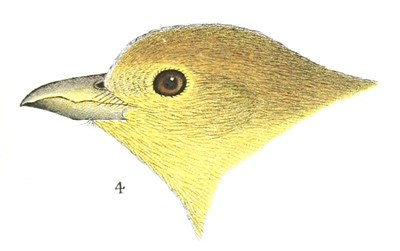

4. Pyranga ludoviciana, Wils. ♀.

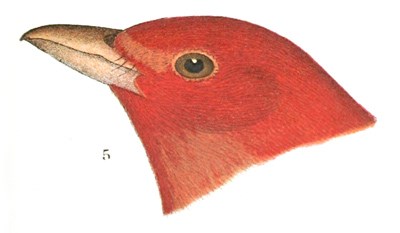

5. Pyranga æstiva, Gm. ♂ Ga., 13190.

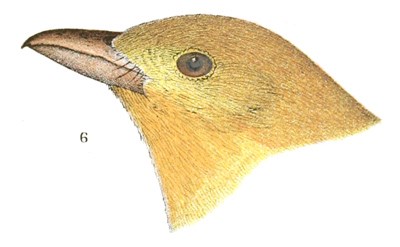

6. Pyranga æstiva, Gm. ♀.

7. Pyranga rubra, Linn. ♂ Iowa, 34177.

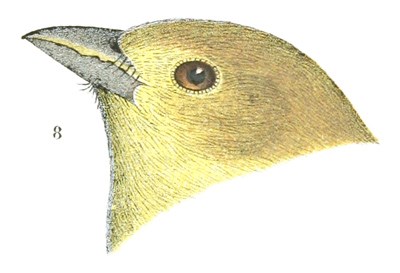

8. Pyranga rubra, Linn. ♀.

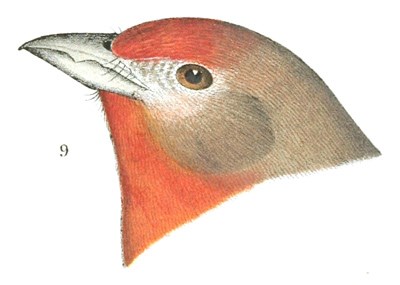

9. Pyranga hepatica, Swains. ♂ Mex., 22414.

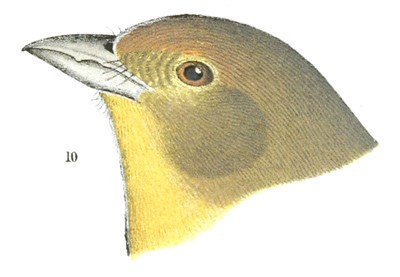

10. Pyranga hepatica, Swains. ♀.

Pyranga æstiva, var. cooperi, Ridgway

Pyranga cooperi, Ridgway, Pr. Ac. Nat. Sc. Philad. June, 1869, p. 130, fig. .—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 142.

Sp. Char. Length, 8.60 (fresh specimen); extent, 13.50; wing, 4.24; tail, 3.68; culmen, .84; tarsus, .80. Male. Generally rich pure vermilion, similar to that of æstiva, but lighter, brighter than in eastern examples, and less rosaceous than in Central American specimens. Upper surface scarcely darker than lower, the head above being hardly different from the throat, and abruptly lighter than the back, which, with the wings and tail, is of a much lighter dusky-red than in æstiva; exposed tips of primaries pure slaty-umber, primaries faintly margined terminally with paler (in the type, this character is not apparent, owing to the feathers being somewhat worn; in other specimens, however, it is quite a noticeable feature, although possibly not to be entirely relied on). Female. Above orange-olivaceous, beneath more light yellowish, purest medially; crissum richer yellow than other lower parts, being in some individuals (young males?) intense Indian-yellow, with the inner webs of the tail-feathers margined with the same; quite distinct line of orange-yellow over the lores.

Hab. Upper Rio Grande and Colorado region of Southern Middle Province; south, in winter, along Pacific coast of Mexico as far as Colima.

This bird, quite different from Eastern æstiva, is, however, probably only a representative form of the same species in the Colorado and Upper Rio Grande region, migrating south in winter, through Western Mexico to Colima, as specimens from Texas and Middle Mexico appear to be quite intermediate, at least in form.

Habits. This is a new form, whose claim to distinctness was first made known by Mr. Ridgway, in 1869. In appearance, it most resembles the P. æstiva, but is larger. It has been found in the Middle Province of the United States, from Fort Mohave at the north, to Colima and Mazatlan in Mexico.

Dr. Cooper found this bird quite common near Fort Mohave, after April 25, in the Colorado Valley, latitude 35°. They chiefly frequented the tall cottonwood, feeding on insects, and occasionally flew down to the Larrea bushes after a kind of bee found on them. He states also that they have a call-note sounding like the words ke-dik, which, in the language of the Mojave Indians, signifies “come here.” They sing in a loud, clear tone, and in a style much like that of the Robin, but with a power of ventriloquism which makes the sound appear much more distant than it really is. The only specimens of this species known to have been obtained in the United States were taken at Los Pinos, New Mexico, by Dr. Coues, and at Fort Mohave by Dr. Cooper. Other specimens have been procured from Western Mexico.

Family FRINGILLIDÆ.—The Finches

Char. Primaries nine. Bill very short, abruptly conical, and robust. Commissure strongly angulated at base of bill. Tarsi scutellate anteriorly, but the sides with two undivided plates meeting behind along the median line, as a sharp posterior ridge. Eyes hazel or brown, except in Pipilo, where they are reddish or yellowish. Nest and eggs very variable as to character and situation.

I still labor under the inability expressed in Birds of North America (p. 406), in 1858, to satisfactorily define and limit the subfamilies and genera of the Fringillidæ of North America, and can only hope that by the aid of the figures of the present work no material difficulty will be experienced in determining the species. The distinctions from the allied families are also difficult to draw with precision. This is especially the case with the Tanagridæ, where we have much the same external anatomy, including the bill, nearly all the varying peculiarities of this member in the one being repeated in the other.—S. F. B.

All the United States species may be provisionally divided into four subfamilies (the European House-Sparrow forming a fifth), briefly characterizable as follows:—

Coccothraustinæ. Bill variable, from enormously large to quite small; the base of the upper mandible almost always provided with a close-pressed fringe of bristly feathers (more or less conspicuous) concealing the nostrils. Wings very long and pointed, usually one half to one third longer than the forked or emarginate tail. Tarsi short.

Pyrgitinæ. Bill robust, swollen, arched above without distinct ridge. Lower mandible at base narrower than upper. Nostrils covered; side of maxilla with stiff appressed bristles. Tarsi short, not longer than middle toe. Tail shorter than the somewhat pointed wings. Back streaked; under parts not streaked.

Spizellinæ. Embracing all the plain-colored sparrow-like species marked with longitudinal stripes. Bill conical, always rather small; both mandibles about equal. Tarsi lengthened. Wings and tail variable. Lateral claws never reaching beyond the base of the middle claw.

Passerellinæ. Sparrow-like species, with triangular spots beneath. Legs, toes, and claws very stout; the lateral claws reaching nearly to the end of the middle ones.

Spizinæ. Brightly colored species, usually without streaks. Bill usually very large and much curved; lower mandible wider than the upper. Wings moderately long. Tail variable.

Subfamily COCCOTHRAUSTINÆ.—The true Finches

Char. Wings very long and much pointed; generally one third longer than the more or less forked tail; first quill usually nearly as long as or longer than the second. Tertiaries but little longer, or equal to the secondaries, and always much exceeded by the primaries. Bill very variable in shape and size, the upper mandible, however, as broad as the lower; nostrils rather more lateral than usual; and always more or less concealed by a series of small bristly feathers applied along the base of the upper mandible; no bristles at the base of the bill. Feet short and rather weak. Hind claw usually considerably longer than the middle anterior one; sometimes nearly the same size.

In the preceding diagnosis I have combined a number of forms, all agreeing in the length and acuteness of the wing, the bristly feathers along the base of the bill, the absence of conspicuous bristles on the sides of the mouth, and the shortness of the feet. They are all strongly marked and brightly colored birds, and usually belong to the more northern regions.

The bill is very variable, even in the same genus, and its shape is to a considerable extent of specific rather than of generic importance. The fringe of short bristles along the base of the bill, concealing the nostrils, is not appreciable in Plectrophanes (except in P. nivalis), but the other characteristics given above are all present.

GeneraA. Bill enormously large and stout; the lateral outline as long as that of the skull. Culmen gently curved.

Colors green, yellow, and blackHesperiphona. First quill equal to the second. Wings one half longer than the tail. Lateral claws equal, reaching to the base of the middle claw. Claws much curved, obtuse; hinder one but little longer than the middle.

B. Bill smaller, with the culmen more or less curved; the lateral outline not so long as the skull. Wings about one third longer than the tail, or a little more; first quill shorter than the second. Claws considerably curved and thickened; hinder most so, and almost inappreciably longer or even shorter than the middle anterior one. Tarsus shorter than the middle toes. Lateral toes unequal.

a. Colors red, gray, and black, never streakedPyrrhula. Bill excessively swollen; as broad and as high as long, not half length of head; upper outline much curved. Tail-coverts covering two thirds the tail, which is nearly even, middle and hinder claws about equal.

b. Colors red and gray, or streaked brown and whitePinicola. Bill moderately swollen; longer than high or broad, upper outlines much curved; the tip hooked. Tail-coverts reaching over basal half of tail, which is nearly even. Middle claw longer than hind; outer lateral claw extending beyond base of middle (reaching to it in Pyrrhula and Carpodacus). ♀ and juv. not streaked.

Carpodacus. Bill variable, always more or less curved and swollen; longer than high or broad; the tip not hooked. Tail-coverts reaching over two thirds the tail, which is decidedly forked. Middle and hind claw about equal. ♀ and juv. streaked.

c. Colors black and yellowChrysomitris. Bill nearly straight. Hind claw stouter and more curved, but scarcely longer than the middle anterior one. Outer lateral toe reaching a little beyond the base of the middle claw; shorter than the hind toe. Wings longer and more pointed. Tail quite deeply forked.

C. Hind claw considerably longer than the middle anterior one, with about the same curvature; claws attenuated towards the point, and acute. Lateral toes about equal. Wings usually almost one half longer than the tail, which is deeply forked. Tarsus shorter than middle toe.

a. Points of mandibles overlappingCurvirostra. Tarsus shorter than middle toe. Bill much compressed, elongate falcate, with the points crossing like the blades of scissors. Claws very large; lateral extending beyond the base of the middle. Colors red or gray. Streaked in juv.

b. Points of mandibles not overlappingÆgiothus. Tarsus equal to the middle toe. Bill very acutely conical; outlines and commissure perfectly straight. Lateral toes reaching beyond the base of the middle one. No ridge on the side of the lower mandible. Streaked; a crimson pileum (except in one species).

Leucosticte. Culmen slightly decurved; commissure a little concave. Bill obtusely conical; not sharp-pointed. A conspicuous ridge on the side of the lower mandible. Claws large; the lateral not reaching beyond the base of the middle one. Colors red and brown.

D. Hind claw much the largest; decidedly less curved than the middle anterior one. Tarsus longer than the middle toe. Lateral toes equal; reaching about to the base of the middle claw. Hind toe as long or longer than the middle one. Bill very variable; always more or less curved and blunted. Palate somewhat tuberculate; margins of lower jaw much inflexed. Tail slightly emarginate or even. Wings one half longer than the tail. First quill as long as the second.

Plectrophanes. Colors black and white. With or without rufous nape or elbows. Much white on tail.

Genus HESPERIPHONA, BonapHesperiphona, Bonap. Comptes Rendus, XXXI, Sept. 1850, 424. (Type, Fringilla vespertina.)

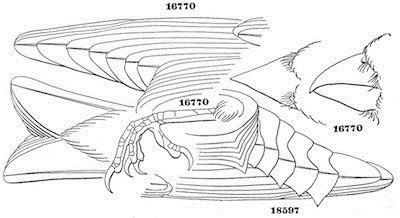

16770, Hesperiphona vespertina.

18597, Coccothraustes vulgaris.

Gen. Char. Bill largest and stoutest of all the United States fringilline birds. Upper mandible much vaulted; culmen nearly straight, but arched towards the tip; commissure concave. Lower jaw very large, but not broader than the upper, nor extending back, as in Guiraca; considerably lower than the upper jaw. Gonys unusually long. Feet short; tarsus less than the middle toe; lateral toes nearly equal, and reaching to the base of the middle claw. Claws much curved, stout, and compressed. Wings very long and pointed, reaching beyond the middle of the tail. Primaries much longer than the nearly equal secondaries and tertials; outer two quills longest; the others rapidly graduated. Tail slightly forked; scarcely more than two thirds the length of the wings, its coverts covering nearly three fourths of its extent. Nest and eggs unknown.

This genus is allied to the European Coccothraustes, but differs in wanting the curious expansion of the inner secondaries, as shown in Fig. 18,597. Species are said to occur in Asia, but we have only two in America,—one peculiar to Mexico (H. abeillii), the other H. vespertina.

The American species may be thus distinguished:—

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Wings and tail black, the tertials with more or less whitish; body concolored, with more or less of a yellowish tinge. ♂. Body yellowish, more olivaceous above; no white at base of primaries. ♀. Body grayish, merely tinged with yellow; a white spot at base of primaries. Nest and eggs unknown.

1. H. vespertina. ♂. Head olivaceous-sepia, with a yellow frontal crescent and a black occipital patch. ♀. Crown plumbeous-brown; a dusky “bridle” down side of the throat; upper tail-coverts tipped with a white spot.

Yellow frontal crescent broad, as wide as the black behind it; inner webs of tertials partially black; secondaries and inner webs of tail-feathers tipped with white. Hab. Northern mountain regions of United States and interior of British America … var. vespertina.

Yellow frontal crescent narrow, less than half as wide as the black behind it; inner webs of the tertials without any black; secondaries and inner webs of tail-feathers without white tips. Hab. Southern Rocky Mountains of United States, and mountains of Mexico. … var. montana.

2. H. abeillii.108 ♂. Head entirely black, sharply defined. ♀. Crown (only) black; no dusky “bridle” on side of throat; upper tail-coverts without white tips. Hab. Mountains of Guatemala and Southern Mexico.

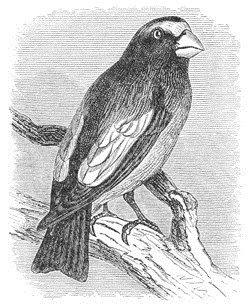

Hesperiphona vespertina, BonapEVENING GROSBEAKFringilla vespertina, Cooper, Annals New York Lyceum, N. H. I, ii, 1825, 220 (Sault St. Marie).—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 515; V, 235, pl. ccclxxiii, ccccxxiv. Fringilla (Coccothraustes) vespertina, Bon. Syn. 1828, 113.—Ib. Am. Orn. II, pl. xv. Coccothraustes vespertina, Sw. F. Bor. Am. II, 1831, 269.—Aud. Birds Am. III, 1841, 217, pl. ccvii. Hesperiphona vespertina, Bon. Comptes Rendus, XXXI, Sept. 1850, 424.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 409.—Cooper & Suckley, 195.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 174. Coccothraustes bonapartii, Lesson, Illust. de Zoöl. 1834, pl. xxxiv. ♀ (Melville Island). Loxia bonapartii, Less. Bull. Sc. tab. xxv. Hesperiphona vespertina, var. vespertina, Ridgway (new variety from Mexico and the southern Rocky Mountains).

Sp. Char. Bill yellowish-green, dusky at the base. Anterior half of the body dusky yellowish-olive, shading into yellow to the rump above, and the under tail-coverts below. Outer scapulars, a broad frontal band continued on each side over the eye, axillaries, and middle of under wing-coverts yellow. Feathers along the extreme base of the bill, the crown, tibiæ, wings, upper tail-coverts, and tail black; inner greater wing-coverts and tertiaries white. Length, 7.30; wing, 4.30; tail, 2.75.

The female differs in having the head of a dull olivaceous-brown, which color also glosses the back. The yellow of the rump and other parts is replaced by a yellowish-ash. The upper tail-coverts are spotted with white. The white of the wing is much restricted. There is an obscure blackish line on each side of the chin.

Hab. (var. vespertina.) Pacific coast to Rocky Mountains; Northern America east to Lake Superior. (var. montana.) Southern Rocky Mountains of United States into Mexico; Orizaba! (Sclater, 1860, 251); Vera Cruz (alpine regions, breeding) Sumichrast, Pr. Bost. Soc. I, 550; Guatemala, Salvin.

Hesperiphona vespertina.

The variety with broad frontal band and increased amount of white appears to characterize Northern specimens, while that with narrow frontlet and the greatest amount of black is found in Guatemala, Mexico, and the southern Rocky Mountains, and may be called montana.

In size it is also a little smaller. Specimens from Mirador (where breeding) and those from New Mexico are nearly identical in size, proportions, and colors.

Habits. This remarkable Grosbeak was first described by Mr. William Cooper, from specimens obtained by Mr. Schoolcraft in April, 1823, near the Sault Sainte Marie, in Michigan. Sir John Richardson soon after found it to be a common inhabitant of the maple groves on the plains of the Saskatchewan, where it is called by the Indians the “Sugar-Bird.” He states that it frequents the borders of Lake Superior also, and the eastern declivity of the Rocky Mountains, in latitude 56°.

Captain Blakiston did not find this Grosbeak on the Saskatchewan during the summer, but only noticed it there during the winter. He saw none after the 22d of April, and not again until the middle of November. They were seen in company with the Pine Grosbeak, feeding on the keys of the ash-leaved maple. He adds that it has a sharp clear note in winter, and is an active bird.

Dr. Cooper, in his Notes on the Zoölogy of Washington Territory, states that this species is a common resident in its forests, but adds that as it frequents the summits of the tallest trees, its habits have been but little observed. In January, 1854, during a snow-storm, a flock descended to some low bushes at Vancouver, and began to eat the seeds. Since then he had only seen them flying high among the tops of the poplars, upon the seeds of which they feed. They were uttering their loud, shrill call-notes as they flew.

The same writer, in his Report on the birds of California, makes mention of the occurrence of this Grosbeak at Michigan Bluffs, in Placer County, in about latitude 39°. Specimens were obtained by Mr. F. Gruber, and were probably the variety designated as montana. The same form doubtless occurs along the summits of the Sierra Nevada, and they have been traced among the Rocky Mountains to Fort Thorn in New Mexico.