полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

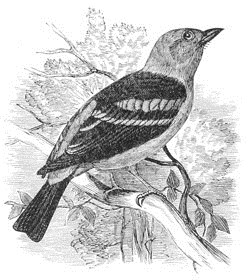

Sp. Char. Bill shorter than the head. Second quill longest; first and third a little shorter. Tail moderately forked. Male. Whole head and body continuous, pure, intense scarlet, the feathers white beneath the surface, and grayish at the roots. Wings and tail, with the scapulars, uniform intense black; the middle-coverts sometimes partly red, forming an interrupted band. Lining of wing white. A blackish tinge along sides of the rump, concealed by wings. Bill pea-green; iris brown; tarsi and toes dull blue. Female. Olive-green above, yellowish beneath. Wing and tail feathers brown, edged with olivaceous. Length, 7.40; wing, 4.00; tail, 3.00.

Hab. Eastern Province North America, north to Winnepeg (west to El Paso? Heermann). In winter, south to Ecuador (Rio Napo, Scl.). Bogota (Scl.) Cuba (Scl. & Gundl.); Jamaica (Scl. & Gosse); Panama (Lawr.); Costa Rica (Lawr.); Vera Cruz (winter, Sumichrast).

Pyranga ludoviciana.

At least three years seem to be required for the assumption of the perfect plumage of the male. In the first year the young male is like the female, but has black wings and tail; in the fall red feathers begin to make their appearance, and the following spring the red predominates in patches.

Habits. The Scarlet Tanager is one of the most conspicuous and brilliant of all our summer visitants. Elegant in its attire, retiring and modest in manners, sweet in song, and useful in its destruction of hurtful insects, it well merits a cordial welcome. This Tanager is distributed over a wide extent of territory, from Texas to Maine, and from South Carolina to the northern shores of Lake Huron, in all which localities it breeds. A few are found once in a while as far east as Calais, in the spring, and they are rather occasional than common in Eastern Massachusetts, but are more plentiful in the western part of the State, becoming quite common about Springfield, arriving May 15, and remaining about four months, breeding in high open woods and old orchards. In South Carolina it is abundant as a migrant, though a few remain and breed in the higher lands. Mr. Audubon states, also, that a few breed in the higher portions of Louisiana, and Dr. Heermann found them breeding at El Paso, in New Mexico. They are far more abundant, however, in the States of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Virginia, and throughout the Mississippi Valley, arriving early in May, and leaving in October. Though occasionally found in the more sparsely settled portions of the country, in orchards and retired gardens, they are, as a rule, inhabitants of the edges of forests.

Their more common notes are simple and brief, resembling, according to Wilson, the sounds chip-charr. Mr. Ridgway represents them by chip-a-ra´-ree. This song it repeats at brief intervals and in a pensive tone, and with a singular faculty of causing it to seem to come from a greater than the real distance. Besides this it also has a more varied and musical chant resembling the mellow notes of the Baltimore Oriole. The female also utters similar notes when her nest is approached, and in their mating-season, as they move together through the branches, they both utter a low whispering warble in a tone of great sweetness and tenderness. As a whole, this bird may be regarded as a musical performer of very respectable merits.

The food of this species is chiefly gleaned among the upper branches, and consists of various coleopterous and other insects and their larvæ. Later in the season they consume various kinds of wild berries.

When their nest is approached, the male bird usually keeps at a cautious distance, as if fearful of being seen, but his much less gaudy mate hovers about the intruder in the greatest distress. Wilson relates quite a touching instance of the devotion of the parent of this species to its young. Having taken a young bird from the nest, and carried it to his friend, Mr. Bartram, it was placed in a cage, and suspended near a nest containing young Orioles, in hopes the parents of the latter would feed it, which they did not do. Its cries, however, attracted its own parent, who assiduously attended it and supplied it with food for several days, became more and more solicitous for its liberation, and constantly uttered cries of entreaty to its offspring to come out of its prison. At last this was more than Mr. Bartram could endure, and he mounted to the cage, took out the prisoner, and restored it to its parent, who accompanied it in its flight to the woods with notes of great exultation.

Early in August the male begins to moult, and in the course of a few days, dressed in the greenish livery of the female, he is not distinguishable from her or his young family. In this humble garb they leave us, and do not resume their summer plumage until just as they are re-entering our southern borders, when they may be seen in various stages of transformation.

This species is extremely susceptible to cold, and in late and unusually chilly seasons large numbers often perish in their more northern haunts, as Massachusetts and Northern New York.

The nests of the Scarlet Tanager are built late in May, or early in June, on the horizontal branch of a forest tree, usually on the edge of a wood, but occasionally in an orchard. They are usually very nearly flat, five or six inches in diameter, and about two in height, with a depression of only about half an inch. They are of somewhat irregular shape, or not quite symmetrically circular. Their base is somewhat loosely constructed of coarse stems of vegetables, strips of bark, and the rootlets of wooded plants. Upon this is wrought, with more compactness and neatness, a framework, within which is the lining, of long slender fibrous roots, interspersed with which are slender stems of plants and a few strips of fine inner bark.

Mr. Nuttall describes a nest examined by him as composed of rigid stalks of weeds and slender fir-twigs tied together with narrow strips of Apocynum and pea-vine runners, and lined with slender wiry stalks of the Helianthemum, the whole so thinly plaited as readily to admit the light through the interstices.

The eggs, four or five in number, vary in length from an inch to .90, and have an average breadth of .65. Their ground-color varies from a well-marked shade of greenish-blue, to a dull white with hardly the least tinge of blue. The spots vary in size, are more or less confluent, and are chiefly of a reddish or rufous brown, intermingled with a few spots of a brownish and obscure purple.

Pyranga ludoviciana, BonapLOUISIANA TANAGERTanagra ludoviciana, Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 27, pl. xx, f. 1.—Bon. Obs. 1826, 95.—Aud. Orn. Biog. IV, 1838, 385; V, 1839, 90, pl. cccliv, cccc. Tanagra (Pyranga) ludoviciana, Bonap. Syn. 1828, 105.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1832, 471. Pyranga ludoviciana, Rich. List, 1837.—Bonap. List, 1838.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 137.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 211, pl. ccx.—Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1856, 125.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 145. Pyranga erythropis, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict. XXVIII, 1819, 291. (“Tanagra columbiana, Jard. ed. Wilson, I, 317,” according to Sclater, but I cannot find such name.)

Sp. Char. Bill shorter than the head. Tail slightly forked; first three quills nearly equal. Male. Yellow; the middle of the back, the wings, and the tail black. Head and neck all round strongly tinged with red; least so on the sides. A band of yellow across the middle coverts, and of yellowish-white across the greater ones; the tertials more or less edged with whitish. Female. Olive-green above, yellowish beneath; the feathers of the interscapular region dusky, margined with olive. The wings and tail rather dark brown, the former with the same marks as the male. Length, 7.25; wing, 3.60; tail, 2.85.

Hab. Western portions of United States, from the Missouri Plains to the Pacific; north to Fort Liard, south to Cape St. Lucas. Oaxaca (Scl.); Guatemala (Scl.); Orizaba (Scl.); Vera Cruz (winter, Sumichrast).

Habits. This bird is one of the many instances in which Wilson has been unfortunate in bestowing upon his new species a geographical name not appropriate at the present time. We have no evidence that this bird, called the Louisiana Tanager, is ever found within the modern limits of that State, although it occurs from the Great Plains to the Pacific, and from Fort Liard, in the northern Rocky Mountains, to Mexico.

It was first met with by Lewis and Clark’s party, on the Upper Missouri, a region then known as Louisiana Territory. They were said to inhabit the extensive plains in what was then called Missouri Territory, building their nests in low bushes, and even among the grass, and delighting in the various kinds of berries with which those fertile prairies were said to abound.

Mr. Nuttall, who met with these birds in his Western excursions, describes them as continually flitting over those vast downs, occasionally alighting on the stems of some tall weed, or the bushes bordering the streams. Their habits are very terrestrial, and from this he infers that they derive their food from the insects they find near the ground, as well as from the seeds of the herbage in which they chiefly dwell. He found them a common and numerous species, remaining in the country west of the Mississippi until the approach of October. In his first observations of them he states that though he had seen many of these birds, yet he had no recollection of hearing them utter any modulated or musical sounds. They appeared to him shy, flitting, and almost silent.

He first observed these birds in a thick belt of wood near Laramie’s Fork of the Platte, at a considerable distance east of the Black Hills. He afterwards found them very abundant, in the spring, in the forests of the Columbia, below Fort Vancouver. In these latter observations he modified his views as to their song, and states that he could frequently trace them by their notes, which are a loud, short, and slow, but pleasing warble, not very unlike that of the common Robin, delivered from the tops of lofty fir-trees. Their music continues, at short intervals, during the forenoon, and while they are busily engaged in searching for larvæ and coleopterous insects, on the small branches of the trees.

Dr. Suckley found this Tanager quite abundant at certain seasons in the vicinity of Fort Steilacoom. In one year a very limited number were seen; in another they were very abundant. From frequent opportunities to examine and to study their habits, he was inclined to discredit the statement of Nuttall that they descend to low bushes, the reverse being the rule. He found it very difficult to meet with any sufficiently low down in the trees for him to kill them with fine shot. Their favorite abode, in the localities where he observed them, was among the upper branches of the tall Abies douglassii. They prefer the edge of the forests, rarely retiring to the depths. In early summer, at Fort Steilacoom, they could be seen during the middle of the day, sunning themselves in the firs, or darting from one of those trees to another, or to some of the neighboring white oaks on the prairie. Later in the season they were to be seen flying very actively about in quest of insect food for their young. On the 10th of July he saw one carrying a worm in its mouth, showing that its young were then hatched out. During the breeding-season they are much less shy, the males frequently sitting on some low limb, rendering the neighborhood joyous with their delightful melody.

Their stomachs were found filled with insects, chiefly coleoptera; among these were many fragments of the large green Buprestis, found on the Douglass fir-trees.

Dr. Cooper adds to this account, that this bird arrives at Puget Sound about May 15, and becomes a common summer resident in Washington Territory, especially near the river-banks and among the prairies, on which are found deciduous trees. He compares its song to that of its black-winged relative (P. rubra), being of a few notes only, whistled in the manner of the Robin, and sounding as if the bird were quite distant, when in reality it is very near. He met with these birds east of the Rocky Mountains and up to the 49th parallel.

In California the same observer noticed their arrival near San Diego, in small parties, about the 24th of April. The males come in advance of their mates, and are more bold and conspicuous, the females being rarely seen. He saw none of them in the Coast Range toward Santa Cruz, or at Santa Barbara, in summer. He also found them in September, 1860, in the higher Rocky Mountains, near the sources of the Columbia, in latitude 47°. In the fall the young and the old associate in families, all in the same dull-greenish plumage, feeding on the berries of the elder, and other shrubs, without the timidity they manifest in spring.

Mr. J. K. Lord states that he did not once meet with this species west of the Cascade Mountains. He found them on the Spokan Plains and at Colville, where they arrive in June. Male birds were the first to be seen. On their arrival they perch on the tops of the highest pine-trees, and continually utter a low piercing chirp. They soon after pair, and disappear in the forest. Where they breed, Mr. Lord was not able to discover, though he sought high and low for their nests. As he never succeeded in finding them, he conjectured that they must breed on the tops of the loftiest pine-trees. They all leave in September, but do not assemble in flocks.

These Tanagers breed at least as far to the south as Arizona, Dr. Coues having found them a summer resident near Fort Whipple, though rare. They arrive there in the middle of April, and leave late in September.

Mr. Salvin states that this Tanager was found between the volcanoes of Agua and Fuego, at an elevation of about five thousand feet. Specimens were also received from the Vera Paz.

Specimens of this species were taken near Oaxaca, Mexico, by Mr. Boucard, where they are winter residents.

Mr. Ridgway writes that he first met with these Tanagers in July, among the pines of the Sierra Nevada. There its sweet song first attracted his attention, it being almost exactly similar to that of its eastern relative (P. rubra). Afterwards he continually met with it in wooded portions, whether among the willows and cotton wood of the river-valleys, or the cedars and piñons of the mountains. In May, 1868, among the willows and buffalo-berry thickets of the Truckee Valley, near Pyramid Lake, it was very abundant, in company with Grosbeaks and Orioles, feeding upon the buds of the grease-wood (Obione), and later in the summer among the cedars and nut-pines of East Humboldt Mountains, where the peculiar notes of the young arrested his attention, resembling the complaining notes of the Bluebird, but louder and more distinct. In September he noticed them feeding, among the thickets bordering the streams, upon the pulpy fruit of the thorn-apple (Cratægus) that grew plentifully in the thickets. To the eastward it was continually met with, in all wooded portions, as far as they explored.

In manners, it is very similar to the P. rubra. The songs of both birds are very nearly alike, being equally fine, but that of this species is more silvery in tone, and uttered more falteringly. Its usual note of plit-it is quite different from the chip-a-ra´-ree of the P. rubra.

He met with their nest and eggs at Parley’s Park, Utah, June 9, 1869. The nest was on the extreme end of a horizontal branch of a pine, in a grove, flat, and with only a very slight depression, having a diameter of four and a half inches, with a height of only an inch. It was composed externally of only a few twigs and dry wiry stems, and lined almost entirely with fine vegetable rootlets.

The eggs, usually three in number, measure .95 by .66 of an inch. In form they are a rounded-oval. Their ground-color is a light bluish-green, sparingly speckled, chiefly at the larger end, with marking of umber, intermingled with a few dots of lilac.

Pyranga hepatica, SwainsonPyranga hepatica, Swainson, Phil. Mag. I, 1827, 124.—Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1856, 124.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 302, pl. xxxi.—Kennerly, 131.—Ridgway, Pr. A. N. S. 1869, 132.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 144. Phœicosoma hepatica, Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 25. Pyranga azaræ, Woodhouse, Sitgreave’s Expl. Zuñi, 1853, 82 (not of other authors).

Sp. Char. “Length, 8.00”; wing, 4.12; tail, 3.36; culmen, .68; tarsus, .84. Second quill longest, first intermediate between fourth and fifth. Bill somewhat shorter than that of æstiva, but broader and higher at the base, becoming compressed toward the end; a distinct prominent tooth on commissure; its color plumbeous-black, paler, or more bluish plumbeous on lower mandible. Male. Head above brownish-red, purer anteriorly; rest of upper parts and sides brownish-ashy, tinged with reddish; edges of primaries, upper tail-coverts and tail, more reddish. Beneath, medially, fine light scarlet, most intense on the throat, growing gradually paler posteriorly. Lores and orbital region grayish-white; eyelids pale-red; ear-coverts ashy-red.

Female. Above ashy-greenish-olivaceous, brightest on forehead; edges of wing-feathers, upper tail-coverts, and tail more ashy on the back; beneath nearly uniform olivaceous-yellow, purer medially; lores ashy; a superciliary stripe of olivaceous-yellow. Young male similar to the female, but forehead and crown olivaceous-orange, brightest anteriorly; superciliary stripe bright orange, whole throat, abdomen, and breast medially rich yellow, most intense, and tinged with orange-chrome on throat.

Hab. Mountain regions of Mexico and southern Rocky Mountains of United States. Oaxaca (Oct., Sclater); Xalapa (Scl.); Guatemala (Sclater); Vera Cruz (not to alpine regions, Sumichrast).

This species differs from all the others in the great restriction of the red; this being confined principally to the head above, and median lower surface, the lateral and upper parts being quite different reddish-ashy. The shade of red is also peculiar among the North American species, being very fine and light, of a red-lead cast, and most intense anteriorly.

Habits. A single female specimen in full plumage of this beautiful bird was obtained by Dr. Woodhouse in the San Francisco Mountains of New Mexico. It was an adult female, and so far is the only one known to have been found within the limits of the United States. It is not rare in the highlands of Mexico, whence it probably extends into the mountainous portions of the United States.

Specimens have also been procured from Guatemala, and Mr. Boucard met with it at Choapam, a mountainous district in the State of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Nothing is known of its habits.

Pyranga æstiva, var. æstiva VieillSUMMER REDBIRDMuscicapa rubra, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 326. Tanagra æstiva, Gmelin, I, 1788, 889.—Wilson, I, 1810, 95, pl. vi, f. 3.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 232; V, 1839, 518, pl. xliv. Pyranga æstiva, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. XXVIII, 1819, 291.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850.—Aud. Syn. 1839, 136.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 222, pl. ccviii.—Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1855, 156.—Ib. 1856, 123.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 301.—Heermann, P. R. R. X, p. 17.—Ridgway, Pr. A. N. S. 1869, 130.—Maynard, Birds E. Mass. 1870, 109. Phœnisoma æstiva, Sw. Birds, II, 1837, 284. Phœnisoma æstiva, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 25. ? Loxia virginica, Gmelin, I, 1788, 849. (Male changing.) ? Tanagra mississippiensis, Gmelin, I, 1788, 889. Pyranga mississippiensis, Max. Cab. Jour. VI, 1858, 272. Tanagra variegata, Lath. Ind. Orn. I, 1790, 422. (Male changing.) Tangare du Mississippi, Buffon, Ois. V, 63, pl. enl. 741.

Sp. Char. Bill nearly as long as the head, without any median tooth. Tail nearly even, or slightly rounded. Male. Vermilion-red; a little darker above, and brightest on the head. Quills brown, the outer webs like the back. Shafts only of the tail-feathers brown. Bill light horn-color, more yellowish at the edges. Female. Olive above, yellow beneath, with a tinge of reddish. Length, 7.20; wing, 3.75; tail, 3.00; culmen, .70, tarsus, .68.

Hab. Eastern Province United States, north to about 40°, though occasionally straying as far as Nova Scotia; west to borders of the plains. In winter, south through the whole of Middle America (except the Pacific coast) as far as Ecuador and Peru. Cuba; Jamaica.

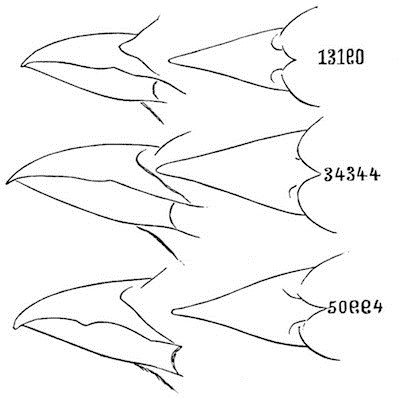

In the accompanying cut we give outline of the bill of the two varieties of Pyranga æstiva as compared with a near ally, P. saira, of South America. (13,190, P. æstiva; 34,344, P. æstiva var. Cooperi; 50,994, P. saira.)

13190

34344

50994

This species is one of wide distribution; its habitat in the United States including the “Eastern Province,” north to Nova Scotia, and west toward the Rocky Mountains, along the streams watering the plains, through Texas, into Eastern Mexico, Central America, and the northern part of South America, as well as some of the West India islands.

In the different regions of its habitat the species undergoes considerable variations as regards shades of color and proportions. Specimens from Texas and Eastern Mexico exhibit a decided tendency to longer bills and more slender forms than those of the Eastern United States; the tails longer, and colors rather purer. In Central America and New Granada the species acquires the greatest perfection in the intensity and purity of the red tints, all specimens being in this respect noticeably different from those of any other region.107

Specimens in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, from Peru (39,849 ♂, 39,849 ♂, and 39,850 ♀, head-waters Huallaga River), are undistinguishable from those killed in the eastern United States.

The young male exhibits a variegated plumage, the red appearing in patches upon the other colors of the female; in its changing plumage, the red generally predominates on the head, and often individuals may be seen with none anywhere else. In this condition there appears to be a great resemblance to the P. erythrocephala (see synoptical table), judging from the description, but which appears to be considerably smaller, and perhaps has the red of the head more continuous and sharply defined.

The young male in first summer resembles the female, but has the yellow tints deeper, the lower tail-coverts approaching orange.

Habits. The Summer Redbird is found chiefly in the Southern States, as far north as Southern New Jersey and Illinois. Mr. Audubon speaks of their occurring in Massachusetts, but Mr. Lawrence has never known of their having been found farther north than the Magnolia Swamps near Atlantic City, N. J. One or two recent instances of the capture of these birds in Massachusetts, as also in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, have occurred, but these must be regarded as purely accidental.

This species is said by Mr. Salvin to enjoy an almost universal range throughout Guatemala. It occurred in December at the mouth of the Rio Dulce, in the pine ridges near Quisigua, and along the whole road from Isabel to Guatemala, a distance of eighty leagues.

Mr. C. W. Wyatt met with these birds also, in all varieties of plumage, throughout Colombia, South America, at Herradura, Cocuta Valley, and Canta. Mr. Boucard obtained them at Plaza Vicente, Mexico. Dr. Woodhouse observed this species throughout the Indian Territory, Texas, and New Mexico, where it seemed solitary in its habits, frequenting the thick scrubby timber. It has been known to breed at various points in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Texas. To the northward it breeds more or less abundantly, as far as Washington, D. C., on the east, and Southern Illinois and Kansas on the west, being much more common in the Mississippi Valley than in the States on the Atlantic in the same parallel of latitude.

Mr. Dresser found it quite common about San Antonio, Texas, during the summer season, arriving there about the middle of April, which is just about the period at which the three specimens were taken near Boston. It is comparatively rare in Pennsylvania, though abundant in the southern counties of New Jersey, and in Delaware, Eastern Maryland, and Virginia. It is also abundant in the Carolinas, in Georgia, Florida, and the Gulf States.