полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

In winter the red is softer and less sharply defined, and usually of a more purplish tint; the markings generally more blended.

Hab. Middle Province of the United States, from Rocky Mountains to the interior valleys of California.

Habits. This form of the House Finch appears to be a very common bird throughout the interior region of the United States, extending to New Mexico and Arizona on the south and southeast, and probably to Mexico. On the Pacific coast it is replaced by another and closely allied variety.

Dr. Woodhouse states that his attention was first called to this interesting little songster while at Sante Fé. It was there known to the American residents as the “Adobe Finch.” By the Mexicans they were called Buriones. He found them exceedingly tame, building about the dwellings, churches, and other buildings, in every nook and corner, and even entering the houses to pick up crumbs. They are never disturbed by the inhabitants. He adds that at the first dawn of the morning they commence a very sweet and clear warble, which he was quite unable to do justice to by any verbal description. He has often in the early morning listened with admiration and gratification to the song of this bird, which is deservedly a great favorite. He found it throughout New Mexico, and beyond. He did not distinguish it from the coast variety.

Dr. Coues also found this bird very abundant in Arizona, where it is a permanent resident, but most abundant in spring and fall. He describes it as eminently gregarious. He found it in all situations, but most common in the spring among the groves of willows and poplars, on the buds of which it feeds. He met with this species all the way from the Rio Grande through New Mexico and Arizona to California, and appears to have noted no differences between this form and the coast variety. He also mentions finding, during a few days’ stay in the New Mexican village of Los Pinos, near Alberquerque, on the Rio Grande, this pretty little Finch the most common and characteristic of the local birds. It was there breeding indifferently in the courtyards, sheds, under porticos or eaves, and also in the forks of trees in the streets. It had sharp conflicts with the Barn Swallows, whose nests it often took possession of, and was a lively and most agreeable feature in the dirty towns which it honored with its presence; and its songs were at once sweet, clear, and exquisitely melodious.

Dr. Cooper met with these birds among the barren and rocky hills near the Colorado.

Mr. Ridgway, who found these birds breeding in large numbers at Pyramid Lake, informs me that their nests were usually placed in clefts in rocks, or in a cave. Near Salt Lake City they were also very common, building their nests among the shrubs known as the wild mahogany, on the hills, but never frequenting the higher regions of the mountains.

The eggs of this bird, which are not distinguishable from those of the Pacific coast form, have a delicate pale-blue ground-color, which is very fugitive, and fades even in the drawers of a cabinet. They are sparingly marked, chiefly around the more obtuse end, with spots and lines of black and a dark brown. They are of oval shape, elongate and pointed at one end, and measure .80 of an inch in length by .60 in breadth.

Carpodacus frontalis, var. rhodocolpus, CabanCALIFORNIA HOUSE-FINCH; RED-HEADED LINNET; BURION? Pyrrhula cruentata, Lesson, Rev. Zoöl. 1839, 101. Carpodacus rhodocolpus, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 166.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1856, 304. Carpodacus frontalis, Bon. & Schleg. Mon. des Lox. 1850, tab. xvi, f. 1.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 533.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 415 (in part).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 156. House Finch, Grayson, Hesperian, II, 1859, 7, plate. Carpodacus familiaris, Heermann, X, 50 (nest).

Sp. Char. (♂ 12,973, Cape St. Lucas.) Head, neck, jugulum, breast, upper part of abdomen and sides, and rump, bright carmine-scarlet, dullest on the centre of the crown and auriculars; rest of the upper parts brownish-gray, glossed with red except on the wings, which have the feathers with distinctly lighter edges. Anal region, flanks, and crissum white, the feathers with shaft-streaks of brown. Wing, 3.00; tail, 2.60; culmen, .45; tarsus, .62; middle toe, .50.

Female and Juv. similar to var. frontalis, but colors darker.

Hab. Coast region of Pacific Province, and peninsula of Lower California.

The male described above represents about the average plumage of this form; an extreme example is No. 26,546, Cape St. Lucas, which is almost entirely of a wine-red color, this covering the whole lower parts, except the anal region, and obliterating the streaks; the wings even are tinged with red. Still, on the head the red (a wine-purple tint) is brightest within those limits to which it is confined in the normal plumage.

Habits. This variety of the House Finch is a very common bird throughout the Pacific coast, from Oregon to Mexico. Mr. Ridgway states that he found this species the most common and familiar of all the birds of the Sacramento Valley. It is a very common cage-bird, being highly prized for its song, which in power is hardly inferior to that of the Canary, while it far surpasses it in sweetness. Its beautiful plumage also renders it still more attractive. The peculiarly soft and musical tweet of this bird is also very similar to that of the Canary, and is very different from the common note of the Purple Finch. This bird breeds very numerously among the shade-trees in the streets of Sacramento, as well as among the oak groves on the outskirts of that city. The males are very shy, but the females, when their nest is disturbed, keep up a lively chirping in an adjoining tree. The nest is generally situated near the extremity of a horizontal branch of a small oak, usually in a grove, occasionally in an isolated tree. In one instance it made use of an abandoned nest of a Bullock’s Oriole, and in another of that of a Cliff Swallow.

Dr. Cooper speaks of this bird as being especially abundant in all the southern portions of California, and also, according to Dr. Newberry, throughout all the valleys northward into Oregon. It is a species that is everywhere peculiar to the valleys, while the others of this genus are equally confined to the wooded mountains. Dr. Cooper also met with this species in the plains near the coast, where there are no plants higher than the wild mustard, on the seeds of which they feed. They also frequent the groves and the open forests on the summits of the coast range, but in small numbers, in company with the C. californicus. They at times feed on buds of trees, and seeds of the cottonwood and other plants. It is most abundant among ranches and gardens where, Dr. Cooper states, it does much mischief by destroying seeds and young plants, fruit and buds. For these depredations even its cheerful and constant song is not regarded as an adequate compensation; and unlike the New-Mexicans in their treatment of its kindred race, the California cultivators wage an unrelenting war upon these birds.

At San Diego, Dr. Cooper found them building as early as the 15th of March, and even a little earlier. Both the situation and the materials of their nest vary. He has found them nesting in trees, on logs and rocks, on the top rail of a picket fence, inside a window-shutter, in the holes of walls, under tiles, on the thatch of a roof, in barns and haystacks, and even between the interstices in the sticks of which the nest of a Hawk had been made, and once in the old nest of an Oriole. About dwellings they always seek the protection of man, and seem to be quite unconscious of having deserved or incurred his enmity. The materials of their nests are usually coarse grasses and weeds, with a lining of hair and fine roots. They raise two, sometimes three, broods in a season, and in the autumn assemble in large flocks, but migrate very little, if any, to the south.

Dr. Cooper states that their songs are very different from those of the other species. They are very varied and very lively, and are heard throughout the year. They are easily kept as cage-birds, but soon lose the beauty of their plumage in confinement, their bright purple colors changing to a dirty yellow.

Nuttall did not observe any of this species in Oregon.

The eggs of this bird vary from four to six in number, and are of a pale blue which readily fades into a bluish-white, and are marked with spots and lines of a dark brown or black. They are of an elongate-oval shape, and measure from .82 to .75 of an inch in length, with an average breadth of .60.

Genus CHRYSOMITRIS, BoieChrysomitris, Boie, Isis, 1828, 322. (Type, Fringilla spinus, Linn.)

Astragalinus, Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 159. (Type, Fringilla tristis, Linn.)

Hypacanthus, Cab. Mus. Hein. 1851, 161. (Type, Carduelis spinoides.)

Chrysomitris tristis.

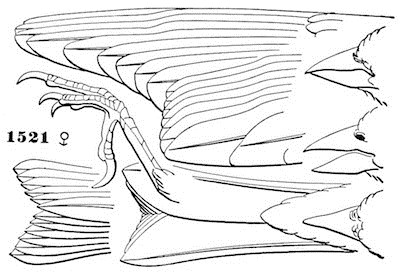

1521 ♀

Gen. Char. Bill rather acutely conic, the tip not very sharp; the culmen slightly convex at the tip; the commissure gently curved. Nostrils concealed. Obsolete ridges on the upper mandible. Tarsi shorter than the middle toe; outer toe rather the longer, reaching to the base of the middle one. Claw of hind toe shorter than the digital portion. Wings and tail as in Ægiothus.

The colors are generally yellow, with black on the crown, throat, back, wings, and tail, varied sometimes with white.

The females want the bright markings of the male.

This genus differs from Ægiothus in a less acute and more curved bill, a much less development of the bristly feathers at the base of the bill, the claw of the hind toe shorter than its digital portion, the claws shorter and less curved and attenuated, and the outer lateral toes not extending beyond the base of the middle claw.

The species exhibit many differences among themselves, especially in the size and shape of the bill, which have been made the basis of generic distinctions. They may be distinguished as follows:—

Species and VarietiesA. No streaks anywhere on plumage; base of tail-feathers black or white. Sexes dissimilar. (Chrysomitris.)

a. No yellow on the wings.

1. C. tristis. Inner webs of tail-feathers always whitish terminally (except in Juv.). ♂. Forehead and crown, wings and tail, deep black; rest of plumage, including the back, rich lemon-yellow; tail-coverts white. ♀. Body grayish above, dingy whitish beneath, stained with yellow; no black on head; wings and tail duller black. Juv. Fulvous-umber above, with markings of reddish-ochraceous on the wings; beneath, dilute-yellow washed with fulvous. Hab. Whole of temperate and warm North America.

2. C. psaltria. Inner webs of tail-feathers never whitish terminally. ♂. Beneath yellow, including the lower tail-coverts; above black, with or without olive-green on the back. ♀. Without any black, the yellow duller.

Tail with white on inner webs; tertials with large white spots.

♂. Auriculars, nape, back, and rump olive-green. Hab. Rocky Mountains of United States … var. psaltria.

♂. Auriculars black; nape, back, and rump green clouded with black. Hab. Arizona … var. arizonæ.

♂. Auriculars, nape, back, and rump entirely black. Hab. Middle America … var. mexicana.

Tail without any white on inner webs; tertials without white spots♂. Auriculars, nape, back, and rump wholly black. Hab. Panama and New Granada … var. columbiana.

b. Terminal half of outer webs of wing-coverts and secondaries yellow.

3. C. lawrencii. Prevailing color ashy, lighter beneath. ♂. A large patch on the breast, the rump, and most of the outer surface of the wing, yellow; forehead, crown, lores, all round base of bill, chin, wings (beneath the yellow), and tail black. ♀. Lacking the black, and with the yellow only indicated. Hab. California and Southwestern Arizona.

B. Whole body and head thickly streaked; bases of tail-feathers yellow. Sexes alike. (Astragalinus.)

4. C. pinus. Above brownish-gray, beneath white, with conspicuous dusky streaks everywhere; two light bands on the wing; bases of secondaries and primaries yellow. Hab. Whole of North America.

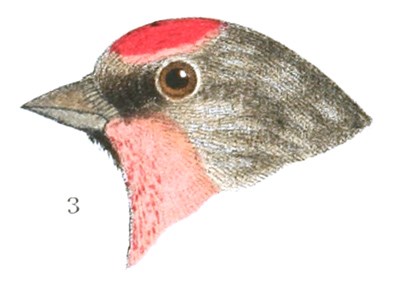

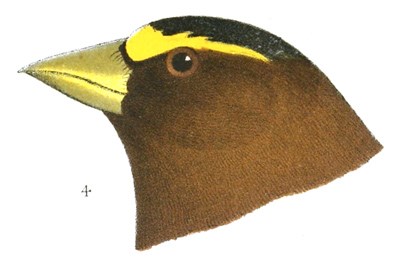

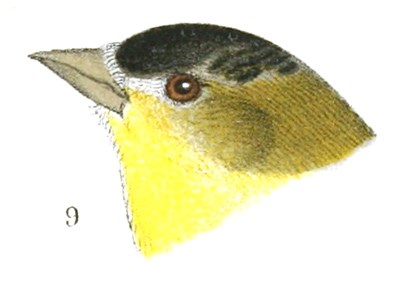

PLATE XXII.

1. Hesperiphona vespertina, var. vespertina. ♂ H. B. Ter., 16770.

2. Ægiothus canescens, var. exilipes. ♂ H. B. Ter., 19686.

3. Ægiothus linaria, var. fuscescens. ♂ Lab’r, 18098. Summer.

4. Hesperiphona vespertina, var. montana. Mex., 35150.

5. Ægiothus linaria, var. fuscescens. Pa., 900. Winter.

6. Ægiothus flavirostris, var. brewsteri. Autumn.

7. Chrysomitris tristis., ♂ Pa., 1531. Summer.

8. Chrysomitris tristis., ad., ♂ Pa., 2205. Winter.

9. Chrysomitris psaltria. ♂ Cal., 6401.

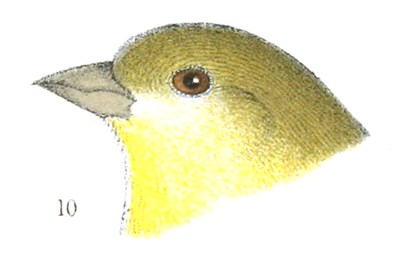

20. Chrysomitris psaltria. ♀ Cal., 3930.

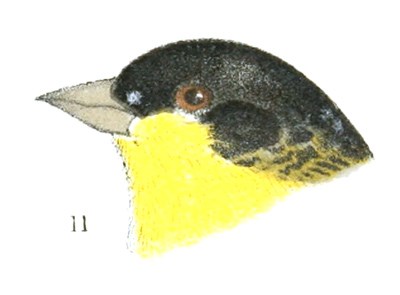

11. Chrysomitris mexicana, var. arizonæ. ♂ Ariz., 37091.

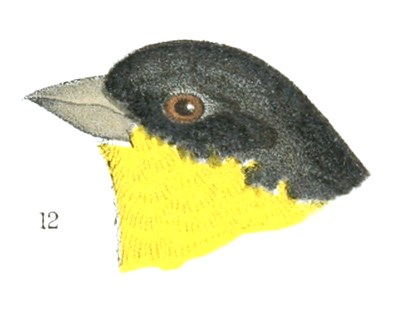

12. Chrysomitris mexicana, var. mexicana. Mex., 4078.

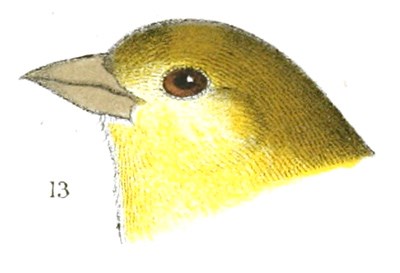

13. Chrysomitris psaltria, var. mexicana. ♀Mex., 22432.

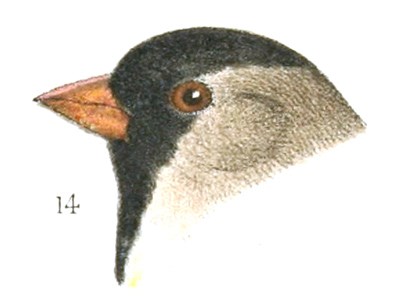

14. Chrysomitris lawrencii. ♂ Cal., 6405.

15. Chrysomitris lawrencii. ♀ Cal., 40836.

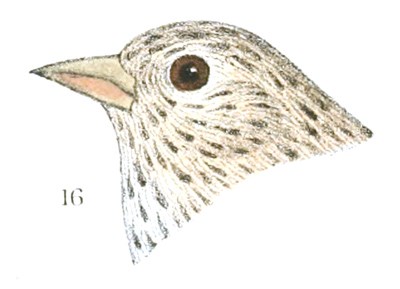

16. Chrysomitris pinus. ♂ Rocky Mts., 11095.

Three species of Chrysomitris, given by Mr. Audubon, are to be erased from the list: C. stanleyi, C. yarrelli, and C. magellanica. If, as he states, he killed specimens of the latter in Kentucky, they must have belonged to the C. notata of Dubus, a Mexican species, not since met with in our limits. The other two were given him as coming from California,—a statement we now know to be incorrect, both belonging to South America.

Chrysomitris tristis, BonYELLOW-BIRD; THISTLE-BIRDFringilla tristis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 320.—Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1808, 20, pl. i, f. 2.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 172; V,, 510, pl. xxxiii. Carduelis tristis, Bon. Obs. Wils. 1825, No. 96.—Aud. Birds Am. II, 1841, 129, pl. clxxxi.—Max. Cab. Journ. vi, 1858, 281. Chrysomitris tristis, Bon. List, 1838.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route; Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VII, IV, 1857, 87.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 421.—Cooper & Suckley, 197.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 167. Astragalinus tristis, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 159 (type). Carduelis americana, (Edwards,) Sw. & Rich. F. B. A. II, 1831, 268. Golden Finch, Pennant. American Goldfinch, Edwards. Chardonneret jaune; Chardonneret du Canada; Tarin de la Nouvelle Yorck, Buffon.—Ib. Pl. enl., pl. ccii, f. 2, pl. ccxcii, f. 1.—Samuels, Birds N. Eng. 288.

Sp. Char. Male. Bright gamboge-yellow; crown, wings, and tail black. Lesser wing-coverts, band across the end of greater ones, ends of secondaries and tertiaries, inner margins of tail-feathers, upper and under tail-coverts, and tibia white. Length, 5.25 inches; wing, 3.00. Female. Yellowish-gray above; greenish-yellow below. No black on forehead. Wing and tail much as in the male. Young. Reddish-olive above; fulvous-yellow below; two broad bands across coverts, and broad edges to last half of secondaries pale rufous.

Hab. North America generally.

In winter the yellow is replaced by a yellowish-brown; the black of the crown wanting, that of wings and tail browner. The throat is generally yellowish; the under parts ashy-brown, passing behind into white.

There are no observable differences between eastern and western specimens.

Chrysomitris tristis.

Habits. The common American Goldfinch is found throughout the greater portion of North America, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Sir John Richardson met with it in the fur regions, where it is one of the tardiest of the summer visitors, and whence it departs early in September. The specimen described by him was taken June 29. At the extreme South it is not uncommon, according to Dresser, around San Antonio, and Dr. Woodhouse found it abundant both in Texas and in the Indian Territory. Dr. Coues did not find it in Arizona, nor does Sumichrast give it as a bird of Vera Cruz. Dr. Newberry found this Finch quite common throughout his route to the Columbia, this sweet songster, he states, having been a constant source of pleasure in the interior both of California and Oregon, far from the haunts of men, where everything else was new and strange. But Dr. Suckley, though he looked carefully for this species about Puget Sound, in the most appropriate situations, was unable to find any, and did not believe that any existed there. Dr. Cooper states that it is, however, quite abundant on the Columbia and along the coast near its mouth.

The last-named writer states that this species is a constant resident in all the western parts of California, but he met with none on the Colorado. They become rare on the coast at the Columbia, but farther in the interior are found as far north as latitude 49°. They breed as far south as San Diego, but seem to avoid the hot interior valleys, as well as the mountains. Their favorite resorts are where thistles and other composite plants abound, and also groves of willow and cottonwood, upon the seeds of which they feed largely. In winter the seeds of the buttonwood supply their chief subsistence.

The common Goldfinch was seen in abundance by Mr. Ridgway only in the vicinity of Sacramento City, associated with the Carpodacus frontalis, and often nesting in the same tree. In the interior this species was rarely seen, and only one specimen was secured in the Truckee Valley in May, and not noticed afterwards. It was, however, found breeding in the Uintah Mountains, where its nest and eggs were obtained. The nests procured by Mr. Ridgway were all found about June 6, except one, ten days later, showing that these birds are four or five weeks earlier in their breeding on the Pacific than on the Atlantic coast. In the Uintah Mountains they were breeding, as at the East, in July.

The Goldfinch is to a large extent gregarious and nomadic in its habits, and only for a short portion of the year do these birds separate into pairs for the purposes of reproduction. During at least three fourths of the year they associate in small flocks, and wander about in an irregular and uncertain manner in quest of their food. They are resident throughout the year in New England, and also throughout the greater portion of the country, their presence or absence being regulated to a large extent by the abundance, scarcity, or absence of their favorite kinds of food. In the winter, the seeds of the taller weeds are their principal means of subsistence. In the summer, the seeds of the thistle and other plants and weeds are sought out by these interesting and busy gleaners. They are abundant in gardens, and as a general thing do very little harm, and a vast amount of benefit in the destruction of the seeds of troublesome weeds. As, however, they do not always discriminate between seeds that are troublesome and those that are desirable, the Goldfinches are unwelcome visitors to the farmers who seek to raise their own seeds of the lettuce, turnip, and other similar vegetables. They are also very fond of the seeds of the sunflower.

Owing possibly to the scarcity of proper food for their young in the early summer, the Goldfinches are quite late before they mate and raise their single brood. It is usually past the 10th of July before their nests are constructed, and often September before their broods are ready to fly.

The song of the Goldfinch—very different from their usual plaintive cry or call-note, uttered as they are flying or when they are feeding—is very sweet, brilliant, and pleasing; most so, indeed, when given as a solo, with no other of its kindred within hearing. I know of none of our common singers that excel it in either respect. Its notes are higher and more flute-like, and its song is more prolonged than that of the Purple Finch. Where large flocks are found in the spring or early summer, the males often join in a very curious and remarkable concert, in which the voices of the several performers do not always accord. In spite of this frequent want of harmony, these concerts are varied and pleasing, now ringing like the loud voices of the Canary, and now sinking into a low soft warble.

During the warm summer weather the Goldfinch is very fond of bathing, and the sandy shelving margins of brooks are always their favorite places of resort for this purpose. I do not think they ever raise more than a single brood in a season in New England, and are in this somewhat irregular, depositing their eggs from July 10 to September, as it may happen.

They usually select a small upright tree, such as a young elm, apple, or pear, or a tall shrub, for their nest, which they rarely place higher than ten feet from the ground. Than the nest of our Goldfinch we have no more beautiful specimen either of the basket in shape or the felted in structure. Symmetrical in form, delicately and beautifully woven, and ingeniously and firmly fastened around the forked twigs with which it is interlaced, it is an exquisite example of architectural beauty and finish. A beautiful specimen from Wisconsin may be taken as typical. It measures three inches in diameter and two in height. The cavity is one and a half inches wide at the rim, and the depth is the same. The base of this nest is a commingling of soft vegetable wool, very fine stems of dried grasses, and fine strips of bark, all being in very fine shreds. The sides, rim, and general exterior of the nest is made up, to a large extent, of fine slender vegetable fibres, interwrought with white and maroon-colored vegetable wool. These materials are closely and densely felted together. The inner nest is softly and thoroughly lined with a softer felting made of the plumose appendages or pappus of the seeds of composite plants.