полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Hab. South Atlantic (and Gulf?) States.

The young bird is quite different from the adult, differing as does that of excubitoroides, but the colors are all darker than in the corresponding age of that species.

Habits. This species, if we regard it as distinct from the excubitoroides, has apparently a very restricted distribution, being confined to the South Atlantic and Gulf States. I am not aware that it has been found farther north than North Carolina. It is not common, according to Audubon, either in Louisiana or Mississippi, and probably only occurs there in the winter. I have had its eggs from South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Dresser speaks of this Shrike as common in Texas in summer, and Dr. Woodhouse states that he found it very abundant in Texas and the Indian Territory. These observations may probably apply to the kindred race, excubitoroides, and not to this form.

It is said to be exclusively a bird of the lowlands, and never to be met with in the mountainous parts, even of its restricted habitat.

Dr. Coues found this species very common in the neighborhood of Columbia, S. C., frequenting the wooded streets and waste fields of that city. On one occasion he observed a Loggerhead busily foraging for insects in the grounds of the Capitol. From the top of a tall bush it would occasionally sally out, capture a large grasshopper, and carry it to a tree near by, full of sharp twigs. It would then proceed to impale the insect on one of these points, remain awhile watching the result of its performance, and then resume its post on the bush, watching for more grasshoppers, some of which, one by one, it caught and impaled in like manner, others it ate on the spot.

This curious habit of impaling insects, more or less common to the entire family of Shrikes, seems to admit of no satisfactory explanation. In this case the bird thus secured them when apparently hungry, eating some and impaling others. Yet, so far as I know, it never makes any use of those it thus impales.

Mr. Audubon states that in South Carolina it is quite common along the fences and hedges about the rice plantations at all seasons, and that it renders good service to the planters in the destruction of field-mice, as well as of many of the larger insects. He speaks of its song as consisting only of shrill, clear, creaking, prolonged notes, resembling the grating of a rusty hinge. His account differs, in many respects, from the more minute and exact descriptions of Rev. Dr. Bachman. In pursuing its prey, he states that it invariably strikes it with its bill before seizing it with its claws.

In reference to its song, Dr. Bachman states that it has other notes besides the grating sound mentioned by Audubon. During the breeding-season, and nearly all the summer, the male bird posts itself at the top of some tree and makes an effort at a song, which he compares to the first attempts of a young Brown Thrush. This is a labored effort, and at times the notes are not unpleasing, but very irregular.

Dr. Bachman also claims that the male evinces marked evidences of attachment to his mate, carrying to her, every now and then, a grasshopper or a cricket, and driving away hawk or crow as they approach the nest.

He also states that he has usually found the nest on the outer limbs of trees, often from fifteen to thirty feet from the ground, and only once on a bush so low as ten feet from the ground. He has occasionally seen these birds feeding on mice, and also on birds that had been apparently wounded by the sportsman. It will sometimes catch young birds and devour them, but its food consists chiefly of grasshoppers, crickets, coleopterous and other insects, including butterflies and moths, which it will pursue and capture on the wing. Dr. Bachman has observed its habit of pinning insects on thorns. In one instance he saw it occupy itself for hours in sticking up, in this way, small fishes thrown on the shore, but he has never known them to devour anything thus impaled.

This Shrike is partially migratory in South Carolina, as a few may be found all winter, but only one tenth of those seen in summer. It is also very fond of the little changeable green lizard, which it pursues with great skill and activity, but not always with success.

It is said also to breed twice in a season. Dr. Bachman describes their eggs as white, and Mr. Audubon speaks of them as greenish-white. Neither make any reference to their spots.

All the nests that I have ever seen of this species, in the simplicity of their structure and in their lack of elaboration, are in remarkable contrast with the nests of both the borealis and the excubitoroides. They are flat, shallow structures, with a height of about two inches and a diameter of five. They are made externally of long soft strips of the inner bark of the basswood, strengthened on the sides with a few dry twigs, stems, and roots. Within, it is lined with fine grasses and stems of herbaceous plants.

The eggs, often six in number, are in length from 1.02 to 1.08 inches, and from .72 to .78 of an inch in breadth; their ground-color is a yellowish or clayey-white, blotched and marbled with dashes, more or less confluent, of obscure purple, light brown, and a purplish-gray. The spots are usually larger and more scattered than in the eggs of C. borealis, and the ground-color is a yellowish and not a bluish white, as in the eggs of C. excubitoroides.

Collurio ludovicianus, var. robustus, BairdWHITE-WINGED SHRIKE?? Lanius elegans, Sw. F. B. A. II, 1831, 122.—Nuttall, Man. I, 1840, 287.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1857, 213.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 327. Collyrio elegans, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 328. Collurio elegans, Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1864, 444.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 140. (According to Dresser & Sharpe, P. Z. S. 1870, 595, who have examined the type, the L. elegans of Swainson is the same as L. lahtora, Sykes, of Siberia.)

Hab. California?

The description already given is taken from a specimen in the collection of the Philadelphia Academy, labelled as having been collected in California by Dr. Gambel, and is very decidedly different from any of the recognized North American species. Of nearly the size of C. excubitoroides and ludovicianus, it has a bill even more powerful than that of C. borealis. In its unwaved under parts and uniform color of the entire upper surface, except scapulars, it differs from borealis and excubitoroides, and resembles ludovicianus. In the extension of white over the inner webs of the secondaries, it closely resembles C. excubitor. The great restriction of white at the base of the tail—the four central feathers being entirely black, and the bases of the others grayish-ashy—is quite peculiar to the species.

The specimen in the Philadelphia Academy we originally referred to the L. elegans of Swainson, alleged to have come from the fur countries, as although some appreciable differences presented themselves, especially in the coloration of the tail, these were considered as resulting from an imperfect description. Messrs. Sharpe and Dresser, however, as quoted above, show that Swainson’s type really belongs to L. lahtora, an Old World species. We therefore find it expedient to give a new name to the variety, having no reason to discredit the alleged locality of the specimen.

Collurio ludovicianus, var. excubitoroides, BairdWESTERN LOGGERHEAD; WHITE-RUMPED SHRIKELanius excubitoroides, Swainson, F. B. A. II, 1831, 115 (Saskatchewan).—Gambel, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1847, 200 (Cala.).—Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1857, 213.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1864, 173 (City of Mexico). Collyrio excubitoroides, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 327. Collurio excub. Baird, Rev. Am. B. 1864, 445.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 138. ? Lanius mexicanus, Brehm, Cab. Jour. II, 1854, 145.—Sclater, Catal. 1861, 46 (Mexico). Lanius ludovicianus, Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 191 (Upper Missouri).—Dresser & Sharpe, P. Z. S. 1870, 595.

Hab. Western Province of North America, as far north as Oregon; Middle North America, to the Saskatchewan, and east to Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois; south to Orizaba and Oaxaca, and City of Mexico; Cape St. Lucas.

The precise boundaries between this species and C. ludovicianus are difficult of definition, as the transition is almost insensible.

The young bird is pale fulvous-ash above, everywhere with transverse crescentic bars of dusky. Two bands of mottled pale fulvous across wings, on tips of middle and greater coverts. Tail tipped with ochraceous, the white feathers tinged with the same. Breast and sides with obsolete bars of dusky. Black band on side of head rather obsolete.

In its extreme stage of coloration it differs from ludovicianus in paler and purer color; the ash of back lighter; the under parts brilliant white, not decidedly plumbeous on the sides as in the other, and without so great a tendency to the usual obsolete waved lines (noticed distinctly only in winter or immature birds); the axillars bluish-white, not plumbeous. The white of wings and tail is more extended; the hoary of forehead and whitish of scapulars more distinct. The bristles at base of bill somewhat involving the feathers are black, forming a narrow frontal line, not seen in the other. The most striking difference is in the rump and upper tail-coverts, which are always appreciably and abruptly lighter than the back, sometimes white or only faintly glossed with plumbeous; while in typical specimens of ludovicianus these feathers are scarcely lighter at all, and generally more or less varied with blackish spots at the end. The legs and tail are apparently longer, the latter less graduated. These differences are, however, most appreciable in specimens from the Middle and Western Provinces. Those from the Western States, east of the Missouri River, as far north as Wisconsin, are more intermediate between the two, although still nearest to the Rocky Mountain bird as described; the back darker, the rump and axillars more plumbeous, the sides more bluish. There is little doubt that the examination of series from the States along the Mississippi will show a still closer resemblance to typical C. ludovicianus, and that the gradation between the two extremes will be found to be continuous and unbroken. It therefore seems reasonable to consider them all as one species, varying with longitude and region according to the usual law,—the more western the lighter, with longer tail. The only alternative is to suppose that two species, originally distinct, have hybridized along the line of junction of their respective provinces, as is certainly sometimes the case. The approximation in many respects of coloration of the Shrikes of the Pacific coast to those of the South Atlantic States is not without its importance in the discussion of the subject. However it may be, it is necessary to retain the name of excubitoroides, as representing, whether as species or variety, a peculiar regional form, which must be kept distinctly in mind. The comparatively greater size of the bill in the Cape St. Lucas specimens is seen in other species from this locality (No. 26,438 of adjacent figure).

26438

13600

The intensity of the black front in this species varies considerably, being sometimes very distinct, and again entirely wanting. This may probably be a character of the breeding-season, the dulness of black anterior to the eye and the lighter color of the bill having a close relationship here, as in other species, to maturity, sex, and season.

Habits. This variety was first described from specimens obtained in the territory of the Hudson’s Bay Co. Richardson states that it was not found farther north than the fifty-fourth degree, and there only in the warm and sandy plain of the Saskatchewan. Its manners, he says, are precisely similar to those of the borealis, feeding chiefly on the grasshoppers, which were very numerous on the plains. Mr. Drummond found its nest in the beginning of June, in a bush of willows. It was built of the twigs of the Artemisia and dry grass, and lined with feathers. The eggs were six in number, of a pale yellowish-gray color, with many irregular and confluent spots of oil-green, mixed with a few of smoke-gray.

Mr. Ridgway met with it, in his Western explorations, in all localities, but most frequently among the Artemisia and in the meadow-tracts of the river valleys. It is also seen on all parts of the mountains, among the cedar groves, localities in which the ludovicianus is said never to be found.

Dr. Cooper describes this bird as abundant in all the plains-region of California, but not as far as the Columbia River. South of latitude 38°, they reside all the year. They were abundant about Fort Mohave all winter, and nested as early as the 19th of March in a thorn-bush. They had young early in April. At San Diego they nested later, about April 20. He speaks of their singing as an attempt at a song, the notes being harsh, like those of a Jay, but not imitative. They catch birds, but do so very rarely, depending upon grasshoppers and other insects.

The nests of the excubitoroides, so far as I have had any opportunity to examine them, always exhibit a very marked contrast, in the elaborateness of their structure, to any of the ludovicianus that have fallen under my notice. They resemble those of the borealis in their size and the felted nature of their walls, but are more coarsely and rudely put together. They have an external diameter of about eight inches, and a height of four. The cavity is also large and deep. These nests are always constructed with much artistic skill and pains. The base is usually a closely impacted mass of fine grasses, lichens, mosses, and leaves, intermingled with stout dry twigs. Upon this is wrought a strong fabric of fine wood-mosses, flaxen fibres of plants, leaves, grasses, fur of quadrupeds, and other substances. Intertwined with these are a sufficient number of slender twigs and stems of plants to give to the whole a remarkable strength and firmness. This is often still further strengthened by an external protection woven of stouter twigs and small ends of branches, stems, etc. The whole is then thoroughly and warmly lined with a soft matting of the fur of several kinds of small animals, vegetable down, and a few feathers.

The eggs, five or six in number, measure 1.00 by .73 of an inch, and strongly resemble those of both the borealis and the ludovicianus. Their ground-color is pale greenish-white, over which are marks and blotches, more or less confluent, of lilac, purplish-brown, and light umber.

Mr. Ridgway, who is familiar with this bird in Southern Illinois, informs me that in that section it is a resident species, being abundant during the summer and by no means rare in the winter. It is there, strangely enough, often called the Mocking-Bird, its similar appearance and fondness for the same locality leading some persons to confound these very different birds. In districts where the true Mimus is not common, young birds of this species are frequently taken from their nests and innocently sold to unsuspecting admirers of that highly appreciated songster.

This bird inhabits, almost exclusively, open situations, being particularly fond of waste fields where young honey-locusts (Gleditschia triacanthos) have grown up. Among their thorny branches its nests are almost utterly inaccessible, if beyond the reach of poles. In such localities this bird may often be seen perched in an upright position upon some thorn-bush, or a fence-stake, quietly watching for its prey, remaining nearly an hour at a time motionless except for an occasional movement of the head.

The flight of this bird, Mr. Ridgway adds, is quite peculiar, utterly unlike that of any other bird except the Oreoscoptes montanus, which it only slightly resembles. In leaving its perch it sinks nearly to the ground, describing a curve as it descends, and, passing but a few feet above the surface, ascends in the same manner to the object upon which it is next to light. The flight is performed in an undulating manner, the bird sustaining itself a short time by a rapid fluttering of the wings, and sinking as this motion is suspended. As it flies, the white patch on the wing, with the general appearance of its gray and white plumage, increases its resemblance to the Mocking-Bird.

Though very partial to thorn-trees (honey-locust), other trees having a thick foliage—as those canopied by a tangled mass of wild grapevines—are frequently occupied as nesting-places; while a pair frequently make their home in an apple-orchard, selecting the old untrimmed trees. The situation of the nest varies according to the character of the tree; if in a thorn-bush, it is placed next the trunk, encased within protecting bunches of thorns; but if in an apple-tree, it is situated, generally, near the extremity of a horizontal branch. The number of eggs is generally six, but Mr. Ridgway has several times found seven in one nest. No bird is more intrepid in the defence of its nest than the present one; at such times it loses, apparently, all fear, and becomes almost frenzied with anger, alighting so near that one might grasp it, were he quick enough, and with open mouth and spread wings and tail threatening the intruder, its attacks accompanied by a peculiar crackling noise, interrupted by a harsh, grating qua, qua, qua, slowly repeated, but emphatically uttered.

The habit peculiar to the Shrikes of impaling their victims Mr. Ridgway has observed frequently in this species; for this purpose the long and extremely sharp thorns of the honey-locust serve it admirably; and “spitted” upon them he has found shrews, mice, grasshoppers, spiders, and even a Chimney-Swallow (Chætura pelagica); and, in another instance, but upon the upright broken-off twig of a dead weed in a field, a large spider. He has also known this bird to dart at the cage of a Canary-Bird, and frighten the poor inmate so that it thrust its head between the wires, when it was immediately torn off by the powerful beak of the Butcher-Bird.

The young of this species becomes a very pleasing and extremely docile pet. Mr. Ridgway has known one which, though fully grown, with power of flight uninjured, and in possession of unrestrained freedom, came to its possessor at his call, and accompanied him through the fields, its attachment being rewarded by frequent “doses” of grasshoppers, caught for it. It had been fully feathered before taken from the nest. Unfortunately the vocal capabilities of this Shrike are not sufficient to allow its becoming a general favorite as a pet; for, although possessing considerable talent for mimicry, it imitates only the rudest sounds, while its own notes, consisting of a grating, sonorous qua and a peculiar creaking sound, each with several variations, are anything but delightful.

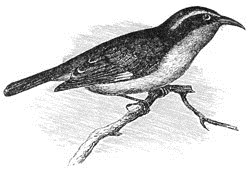

Family CÆREBIDÆ.—The Creepers

As already stated on page 177, there is little to distinguish the Cærebidæ from the Sylvicolidæ, except by the longer and more protracted tongue, and by the narrower gape in some of the forms. The genera Certhiola, Cæreba, Diglossa, etc., have peculiarities by which they are easily recognized; but when we come to such members as Dacnis, Conirostrum, etc., it becomes very difficult to separate them from the slender-billed Tanagers, the Wood Warblers, and the Helminthophagas.

Although the family is one widely distributed, in numerous genera, over Middle and South America, but one, Certhiola, belongs to North America, this being represented by a species, or rather a race, abundant in the Bahamas, and occasionally met with in the Florida Keys. We shall therefore give only the diagnosis of this family.

Genus CERTHIOLA, SundevallCerthiola, Sundevall, Vet. Akad. Handl. Stockholm, 1835, 99. (Type, Certhia flaveola, Linn.)

Certhiola flaveola, Sund.

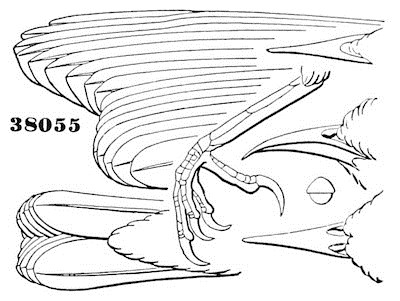

38055

Gen. Char. Bill nearly as long as the head; as high as broad at base, elongated, conical, very acute, and gently decurved from base to tip. Culmen uniformly convex; gonys concave. No bristles at base of bill. Tail rounded, rather shorter than the wings. Tarsi longer than the middle toe. Iris brown? Nest pensile and arched. Eggs with yellowish ground dotted thickly with rufous spots.

This genus is one of those especially characterizing the West Indies, almost every island as far as known having its peculiar species, differing, it is true, in very slight characters, but always constant to the normal type. Cuba alone has so far furnished no representative of this genus, its place being supplied apparently by Cæreba cyanea. The specimens from St. Thomas I cannot distinguish from those of Porto Rico, but this is, so far as the series before me indicates, the only case where one species occurs on two islands. All the West Indian species, nine or ten in number, agree in having the whole upper part nearly uniformly dusky or blackish; the head and back being concolored, while of the three or four South American all but one (C. luteola) have the back more olivaceous, the head much darker. Again, the West Indian species, with a single exception (C. bananivora), have both webs of lateral tail-feathers broadly and about equally tipped with white; while in all the South American this white is more restricted on the inner web, and on the outer reduced to a narrow border. C. caboti from Cozumel, near the eastern coast of Yucatan, exhibits the Continental impress in possessing the character last mentioned.

Certhiola flaveola.

In all the species from the Greater Antilles and the portion of Continental America west and directly south of this group, there is a distinct external white patch at base of quills; while this disappears in the species of the Lesser Antilles and eastern South America, or is only faintly traceable. Again, in the species of the Lesser Antilles, with the disappearance of the white wing-patch, the greater and middle wing-coverts show a faint edging of lighter, by which, as well as by the darker back, they are distinguished from their South American allies.

The shape of the white patch at base of the quills on the outer web furnishes, in combination with the color of the throat, excellent and permanent specific characters. This in the Jamaican, Haytien, and Bahaman forms is elongated, extending gradually and uniformly behind to the outer edge of the quill, while in those of Porto Rico, St. Thomas, Cozumel, and the South American species, where it exists, the posterior outline is nearly transverse, and only running out a little along outer web.

As a general rule South American species have shorter tails than the West Indian.

It is a nice question what are really species in this genus, and what merely races or varieties; but it would probably be not far from correct to assume that the various forms described are simply modifications of one primitive species, produced by geographical distribution and external physical conditions. In the following diagnosis I shall treat all the varieties as occupying the same rank, without attempting any discrimination. Although but one of these belongs to the United States, and that as a straggler from the Bahamas, I give the table of the whole, to show the interesting relationship between them.

Common Characters. Above dusky-olive or blackish; the rump olivaceous or yellowish; the head and cheeks always black, and sometimes darker than back. Chin and throat ashy or black. Rest of under part yellow, duller behind. A broad white stripe from bill above eye to nape. A white patch at base of primaries; generally visible externally, sometimes concealed. Lateral tail-feathers tipped with white. Bill black; legs dusky.