полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

This, reasons Saussure, is obviously an instinctive preparation, on the part of these birds, to provide the means of supporting life during the arid winter months, when no rain falls and everything is parched. His observations were made in April, the last of the winter months; and he found the Woodpeckers withdrawing food from their depositories, and satisfied himself that the birds were eating the acorn itself, and not the diminutive maggots a few of them contained.

The ingenuity with which the bird managed to get at the contents of each acorn was also quite striking. Its feet being unfit for grasping the acorn, it digs a hole into the dry bark of the yuccas, just large enough to receive the small end of the acorn, which it inserts, making use of its bill to split it open, as with a wedge. The trunks of the yuccas were all found riddled with these holes.

There are several remarkable features to be noticed in the facts observed by Saussure,—the provident instinct which prompts this bird to lay by stores of provisions for the winter; the great distance traversed to collect a kind of food so unusual for its race; and its seeking, in a spot so remote from its natural abode, a storehouse so remarkable. Can instinct alone teach, or have experience and reason taught, these birds, that, better far than the bark of trees, or cracks in rocks, or cavities dug in the earth, or any other known hiding-place, are these hidden cavities within the hollow stems of distant plants? What first taught them how to break through the flinty coverings of these retreats? By what revelation could these birds have been informed that within these dry and closed stalks they could, by searching, find suitable places, protected from moisture, for preserving their stores in a state most favorable for their long preservation, safe from gnawing rats, and from those acorn-eating birds whose bills are not strong or sharp enough to cut through their tough enclosures? M. Sumichrast, who afterwards enjoyed unusual opportunities for observing the habits of these Woodpeckers in the State of Vera Cruz, states that they dwell exclusively in oak woods, and that near Potrero, as well as in the alpine regions, trunks of oak-trees are found pierced with small holes in circular lines around their circumference. Into each of these holes these birds drive the acorns by repeated blows of their beaks, so as to fix them firmly. At other times they make their collection of acorns in openings between the raised bark of dry trees and the trunks. This writer states that he has sought in vain to explain such performances satisfactorily. The localities in which these birds reside, in Mexico, teem at all seasons with insects; and it seems absurd, therefore, to suppose that they can be in quest of the small, almost microscopic, larvæ contained in the acorns.

Dr. C. T. Jackson sought to account for these interesting performances on the ingenious hypothesis that the acorns thus stored are always infested with larvæ, and never sound ones; that they are driven into the tree cup-end foremost, so as to securely imprison the maggot and prevent its escape, and thus enable the Woodpecker to devour it at its leisure. This would argue a wonderful degree of intelligence and forethought, on the part of the Woodpecker, and more than it is entitled to; for the facts do not sustain this hypothesis. The acorns are not put into the tree with the cup-end in, but invariably the reverse, so far as we have noticed; and the acorns, so far from being wormy, are, in nine cases out of ten, sound ones. Besides, this theory affords no explanation of the large collections of loose acorns made by these birds in hollow trees, or in the stalks of the maguay plants. Nor can we understand why, if so intelligent, they make so little use of these acorns, as seems to be the almost universal testimony of California naturalists. And, as still further demonstrating the incorrectness of this hypothesis, we have recently been informed by Dr. Canfield of Monterey, Cal., that occasionally these Woodpeckers, following an instinct so blind that they do not distinguish between an acorn and a pebble, are known to fill up the holes they have drilled with so much labor, not only with acorns, but occasionally with stones. In time the bark and the wood grow over these, and after a few years they are left a long way from the surface. These trees are usually the sugar-pine of California, a wood much used for lumber. Occasionally one of these trees is cut, the log taken to mill without its being known that it is thus charged with rounded pieces of flint or agate, and the saws that come in contact with them are broken.

Without venturing to present an explanation of facts that have appeared so contradictory and unsatisfactory to other naturalists, such as we can claim to be either comprehensive or entirely satisfactory, we cannot discredit the positive averments of such observers as Saussure and Salvin. We believe that these Woodpeckers do eat the acorns, when they can do no better. And when we are confronted with the fact, which we do not feel at liberty to altogether disregard, that in very large regions this bird seems to labor in vain, and makes no use of the treasures it has thus heaped together, we can only attempt an explanation. This Woodpecker is found over an immense area. It everywhere has the same instinctive promptings to provide, not “for a rainy day,” but for the exact opposite,—for a long interval during which no rain falls, for nearly two hundred days at a time, in all the low and hot lands of Mexico and Central America. There these accumulations become a necessity, there we are informed they do eat the acorns, and, more than this, many other birds and beasts derive the means of self-preservation in times of famine from the provident labors of this bird. That in Oregon, in California, and in the mountains of Mexico and elsewhere, where better and more natural food offers throughout the year, it is rarely known to eat the acorns it has thus labored to save, only seems to prove that it acts under the influences of an undiscriminating instinct that prompts it to gather in its stores whether it needs them or not.

It may be, too, that writers have too hastily inferred that these birds never eat the acorns, because they have been unable to obtain complete evidence of the fact. We have recently received from C. W. Plass, Esq., some interesting facts, which, if they do not prove that these birds in the winter visit their stores and eat their acorns, render it highly probable. Mr. Plass resides near Napa City, Cal., near which city, and on the edge of the pine forests, he has recently constructed a house. The gable-ends of this dwelling the California Woodpeckers have found a very convenient storehouse for their acorns, and Mr. Plass has very considerately permitted them to do so unmolested. The window in the gable slides up upon pullies its whole length, to admit of a passage to the upper verandah, and the open space in the wall admits of the nuts falling down into the upper hall, and this frequently happens when the birds attempt to extricate them from the outside. Nearly all these nuts are found to be sound, and contain no worm, while those that fall outside are empty shells. Empty shells have also been noticed by Mr. Plass under the trees, indicating that the acorns have been eaten.

The Smithsonian Institution has received specimens of the American race of this Woodpecker, collected at Belize by Dr. Berendt, and accompanied by illustrations of their work in the way of implantation of acorns in the bark of trees.

The eggs of this Woodpecker, obtained by Mr. Emanuel Samuels near Petaluma, Cal., and now in the collection of the Boston Society of Natural History, are undistinguishable from the eggs of other Woodpeckers in form or color, except that they are somewhat oblong, and measure 1.12 inches in length by .90 of an inch in breadth.

Melanerpes formicivorus, var. angustifrons, BairdTHE NARROW-FRONTED WOODPECKERMelanerpes formicivorus, var. angustifrons, Baird, Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 405.

Sp. Char. Compared with M. formicivorus, the size is smaller. The light frontal bar is much narrower; in the female scarcely more than half the black one behind it, and not reaching anything like as far back as the anterior border of the eye, instead of exceeding this limit. The light frontal and the black bars together are only about two thirds the length of the occipital red, instead of exceeding it in length; the red patch reaches forward nearly or quite to the posterior border of the eye, instead of falling a considerable distance behind it, and being much broader posteriorly. The frontal band too is gamboge-yellow, much like the throat, and not white; the connection with the yellow throat-patch much broader. The white upper tail-coverts show a tendency to a black edge. Length, 8.00; wing, 5.20; tail, 3.20.

Hab. Cape St. Lucas.

As the differences mentioned are constant, we consider the Cape St. Lucas bird as forming at least a permanent variety, and indicate it as above. A single specimen from the Sierra Madre, of Colima, is very similar.

Habits. We have no information as to the habits of this singular race of the M. formicivorus, found at Cape St. Lucas by Mr. John Xantus. It will be an interesting matter for investigation to ascertain to what extent the totally different character of the region in which this bird is met with from those in which the M. formicivorus is found, may have modified its habits and its manner of life.

Section COLAPTEÆThis section, formerly embracing but one genus additional to Colaptes, has recently had three more added to it by Bonaparte. The only United States representative, however, is Colaptes.

Genus COLAPTES, SwainsonColaptes, Swainson, Zoöl. Jour. III, Dec. 1827, 353. (Type, Cuculus auratus, Linn.)

Geopicos, Malherbe, Mém. Acad. Metz, 1849, 358. (G. campestris.)

Gen. Char. Bill slender, depressed at the base, then compressed. Culmen much curved, gonys straight; both with acute ridges, and coming to quite a sharp point with the commissure at the end; the bill, consequently, not truncate at the end. No ridges on the bill. Nostrils basal, median, oval, and exposed. Gonys very short; about half the culmen. Feet large; the anterior outer toe considerably longer than the posterior. Tail long, exceeding the secondaries; the feathers suddenly acuminate, with elongated points.

Colaptes auratus.

1341 ♂

There are four well-marked representatives of the typical genus Colaptes belonging to Middle and North America, three of them found within the limits of the United States, in addition to what has been called a hybrid between two of them. The common and distinctive characters of these four are as follows:—

Species and VarietiesCommon Characters. Head and neck ashy or brown, unvaried except by a black or red malar patch in the male. Back and wings brown, banded transversely with black; rump and upper tail-coverts white. Beneath whitish, with circular black spots, and bands on crissum; a black pectoral crescent. Shafts and under surfaces of quills and tail-feathers either yellow or red.

A. Mustache red; throat ash; no red nuchal crescent.

a. Under surface and shafts of wings and tail red.

1. C. mexicanoides.133 Hood bright cinnamon-rufous; feathers of mustache black below surface. Upper parts barred with black and whitish-brown, the two colors of about equal width. Shafts, etc., dull brick-red. Rump spotted with black; black terminal zone of under surface of tail narrow, badly defined. Wing, 6.15; tail, 4.90; bill, 1.77. Hab. Southern Mexico and Guatemala.

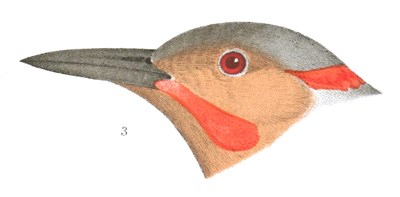

2. C. mexicanus.134 Hood ashy-olivaceous, more rufescent anteriorly, light cinnamon on lores and around eyes; feathers of mustache light ash below surface. Upper parts umber-brown, barred with black, the black only about one fourth as wide as the brown. Shafts, etc., fine salmon-red, or pinkish orange-red. Rump unspotted; black terminal zone of tail broad, sharply defined. Wing, 6.70; tail, 5.00; bill, 1.60. Hab. Middle and Western Province of United States, south into Eastern Mexico to Mirador and Orizaba, and Jalapa.

b. Under surface and shafts of wings and tail gamboge-yellow.

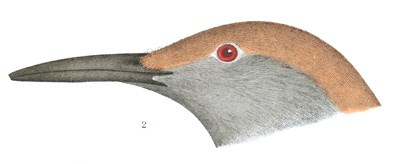

3. C. chrysoides. Hood uniform light cinnamon; upper parts raw umber with sparse, very narrow and distant, bars of black. Rump immaculate; black terminal zone of tail occupying nearly the terminal half, and very sharply defined. Wing, 5.90; tail, 5.70; bill, 1.80. Hab. Colorado and Cape St. Lucas region of Southern Middle Province of United States.

B. Mustache black; a red nuchal crescent. Throat pinkish, hood ashy.

4. C. auratus. Shafts, etc., gamboge-yellow; upper parts olivaceous-brown, with narrow bars of black, about half as wide as the brown.

Rump immaculate; black terminal zone of under surface of tail broad, more than half an inch wide on outer feather. Edges of tail-feathers narrowly edged, but not indented, with whitish. Outer web of lateral feathers without spots of dusky. Wing, 6.10; tail, 4.80; bill, 1.58. Hab. Eastern Province of North America … var. auratus.

Rump spotted with black; black terminal zone of tail narrow, consisting on outer feather of an irregular spot less than a quarter of an inch wide. Edges of all the tail-feathers indented with whitish bars; outer web of lateral feathers with quadrate spots of dusky along the edge. Wing, 5.75; tail, 4.75; bill, 1.60. Hab. Cuba … var. chrysocaulosus.135

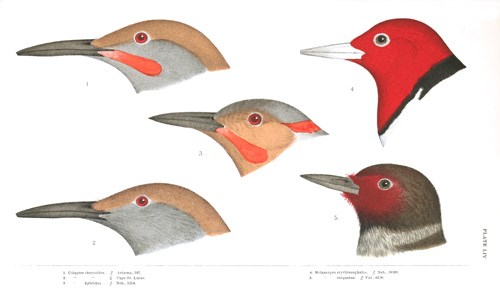

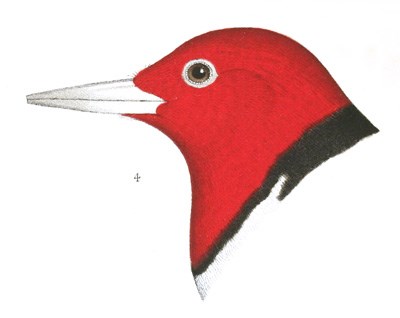

PLATE LIV.

1. Colaptes chrysoides. ♂ Arizona, 107.

2. Colaptes chrysoides. ♀ Cape St. Lucas.

3. Colaptes hybridus. ♂ Neb., 5214.

4. Melanerpes erythrocephalus. ♂ Neb., 38303.

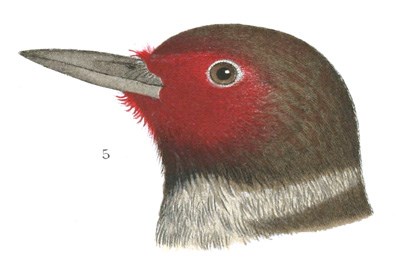

5. Melanerpes torquatus. ♂ Cal., 6138.

Colaptes auratus, SwainsonFLICKER; YELLOW-SHAFTED WOODPECKER; HIGH-HOLDER

Cuculus auratus, Linn. Syst. Nat., I, (ed. 10,) 1758, 112. Picus auratus, Linn. Syst. Nat. 1, (ed. 12,) 1766, 174.—Forster, Phil. Trans. LXII, 1772, 383.—Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 66, pl. cxxiii.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, 1810, 45, pl. iii, f. 1.—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 84.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 191; V, 540, pl. xxxvii.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 282, pl. cclxxiii.—Sundevall, Consp. 71. Colaptes auratus, Sw. Zoöl. Jour. III, 1827, 353.—Ib. F. Bor. Am. II, 1831, 314.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 113.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 118.—Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 420.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 470 (San Antonio, one specimen only seen).—Scl. Cat. 1862, 344.—Gray, Cat. 1868, 120.—Fowler, Am. Nat. III, 1869, 422.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chicago Ac. I, 1869, 275 (Alaska).—Samuels, 105.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 307.

Sp. Char. Shafts and under surfaces of wing and tail feathers gamboge-yellow. Male with a black patch on each side of the cheek. A red crescent on the nape. Throat and stripe beneath the eye pale lilac-brown. Back glossed with olivaceous-green. Female without the black cheek-patch.

Additional Characters. A crescentic patch on the breast and rounded spots on the belly black. Back and wing-coverts with interrupted transverse bands of black. Neck above and on the sides ashy. Beneath pale pinkish-brown, tinged with yellow on the abdomen, each feather with a heart-shaped spot of black near the end. Rump white. Length, 12.50; wing, 6.00.

Hab. All of eastern North America to the eastern slopes of Rocky Mountains; farther north, extending across along the Yukon as far at least as Nulato, perhaps to the Pacific. Greenland (Reinhardt). Localities: San Antonio, Texas, only one specimen (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 470).

Specimens vary considerably in size and proportions; the more northern ones are much the larger. The spots vary in number and in size; they may be circular, or transversely or longitudinally oval. Western specimens appear paler. In a Selkirk Settlement specimen the belly is tinged with pale sulphur-yellow, the back with olivaceous-green.

This species, in general pattern of coloration, resembles the C. mexicanus, although the colors are very different. Thus the shafts of the quills, with their under surfaces, are gamboge-yellow, instead of orange-red. There is a conspicuous nuchal crescent of crimson wanting, or but slightly indicated, in mexicanus. The cheek-patch is pure black, widening and abruptly truncate behind, instead of bright crimson, pointed or rounded behind. The shade of the upper parts is olivaceous-green, instead of purplish-brown. The top of the head and the nape are more ashy. The chin, throat, neck, and sides of the head, are pale purplish or lilac brown, instead of bluish-ash; the space above, below, and around the eye of the same color, instead of having reddish-brown above and ashy below.

The young of this species is sufficiently like the adult to be readily recognizable. Sometimes the entire crown is faintly tipped with red, as characteristic of young Woodpeckers.

Habits. The Golden-winged Woodpecker is altogether the most common and the most widely distributed of the North American representatives of the genus. According to Sir John Richardson, it visits the fur countries in the summer, extending its migrations as far to the north as the Great Slave Lake, and resorting in great numbers to the plains of the Saskatchewan. It was found by Dr. Woodhouse very abundant in Texas and the Indian Territory, and it is given by Reinhardt as occurring in Greenland. Mr. McFarlane found it breeding at Fort Anderson; Mr. Ross at Fort Rae, Fort Resolution, and Fort Simpson; and Mr. Kennicott at Fort Yukon. All this testimony demonstrates a distribution throughout the entire eastern portion of North America, from the Gulf of Mexico almost to the Arctic Ocean, and from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains.

In the more northern portions of the continent this bird is only a summer visitant, but in the Southern and Middle, and to some extent in the New England States, it is a permanent resident. Wilson speaks of seeing them exposed for sale in the markets of Philadelphia during each month of a very rigorous winter. Wilson’s observations of their habits during breeding, made in Pennsylvania, were that early in April they begin to prepare their nest. This is built in the hollow body or branch of a tree, sometimes, though not always, at a considerable height from the ground. He adds that he has frequently known them to fix on the trunk of an old apple-tree, at a height not more than six feet from the root. He also mentions as quite surprising the sagacity of this bird in discovering, under a sound bark, a hollow limb or trunk of a tree, and its perseverance in perforating it for purposes of incubation. The male and female alternately relieve and encourage each other by mutual caresses, renewing their labors for several days, till the object is attained, and the place rendered sufficiently capacious, convenient, and secure. They are often so extremely intent upon their work as to be heard at their labor till a very late hour in the night. Wilson mentions one instance where he knew a pair to dig first five inches straight forward, and then downward more than twice that distance, into a solid black-oak. They carry in no materials for their nest, the soft chips and dust of the wood serving for this purpose. The female lays six white eggs, almost transparent, very thick at the greater end, and tapering suddenly to the other. The young soon leave the nest, climbing to the higher branches, where they are fed by their parents.

According to Mr. Audubon this Woodpecker rears two broods in a season, the usual number of eggs being six. In one instance, however, Mr. MacCulloch, quoted by Audubon, speaks of having found a nest in a rotten stump, which contained no less than eighteen young birds, of various ages, and at least two eggs not quite hatched. It is not improbable that, in cases where the number of eggs exceeds seven or eight, more females than one have contributed to the number. In one instance, upon sawing off the decayed top of an old tree, in which these birds had a nest, twelve eggs were found. These were not molested, but, on visiting the place a few days after, I found the excavation to have been deepened from eighteen to twenty-four inches.

Mr. C. S. Paine, of Randolph, Vt., writing in October, 1860, furnishes some interesting observations made in regard to these birds in the central part of that State. He says, “This Woodpecker is very common, and makes its appearance about the 20th of April. Between the 1st and the 15th of May it usually commences boring a hole for the nest, and deposits its eggs the last of May or the first of June.” He found three nests that year, all of which were in old stumps on the banks of a small stream. Each nest contained seven eggs. The boy who took them out was able to do so without any cutting, and found them at the depth of his elbow. In another nest there were but three eggs when first discovered. The limb was cut down nearly to a level with the eggs, which were taken. The next day the nest had been deepened a whole foot and another egg deposited. Mr. Paine has never known them go into thick woods to breed, but they seem rather to prefer the edges of woods. He has never known one to breed in an old cavity, but in one instance a pair selected a partially decayed stump for their operations. When they are disturbed, they sometimes fly around their nests, uttering shrill, squeaking notes, occasionally intermixing with them guttural or gurgling tones.

It is probably true that they usually excavate their own burrow, but this is not an invariable rule. In the fall of 1870 a pair of these Woodpeckers took shelter in my barn, remaining there during the winter. Although there were abundant means of entrance and of egress, they wrought for themselves other passages out and in through the most solid part of the sides of the building. Early in the spring they took possession of a large cavity in an old apple-tree, directly on the path between the barn and the house, where they reared their family. They were very shy, and rarely permitted themselves to be seen. The nest contained six young, each of which had been hatched at successive intervals, leaving the nest one after the other. The youngest was nearly a fortnight later to depart than the first. Just before leaving the nest, the oldest bird climbed to the opening of the cavity, filling the whole space, and uttering a loud hissing sound whenever the nest was approached. As soon as they could use their wings, even partially, they were removed, one by one, to a more retired part of the grounds, where they were fed by their parents.

Throughout Massachusetts, this bird, generally known as the Pigeon Woodpecker, is one of the most common and familiar birds. They abound in old orchards and groves, and manifest more apparent confidence in man than the treatment they receive at his hands seems to justify. Their nests are usually constructed at the distance of only a few feet from the ground, and though Wilson, Audubon, and Nuttall agree upon six as the average of their eggs, they frequently exceed this number. Mr. Audubon gives as the measurement of the eggs of this species 1.08 inches in length and .88 of an inch in breadth. Their length varies from 1.05 to 1.15 inches, and their breadth from .91 to .85 of an inch. Their average measurement is 1.09 by .88 of an inch.

Colaptes mexicanus, SwainsonRED-SHAFTED FLICKERColaptes mexicanus, Sw. Syn. Mex. Birds, in Philos. Mag. I, 1827, 440.—Ib. F. Bor. Am. II, 1831, 315.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route, 91; P. R. R. Rep. VI, 1857.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 120.—Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 420, mixed with hybridus.—Lord, Proc. R. Art. Inst. I, IV, 112.—Cooper & Suckley, 163.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1858, 309 (Oaxaca).—Ib. Cat. 1862, 344.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 470 (San Antonio, rare).—Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 56.—Sumichrast, Mem. Bost. Soc. I, 1869, 562 (alpine district, Vera Cruz).—Gray, Cat. 1868, 121.—Dall & Bannister, Pr. Chicago Ac. I, 1869, 275 (Alaska).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 408. Picus mexicanus, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 174, pl. ccccxvi.—Ib. Birds America, IV, 1842, 295, pl. cclxxiv.—Sundevall, Consp. 72. Colaptes collaris, Vigors, Zoöl. Jour. IV, Jan. 1829, 353.—Ib. Zoöl. Beechey’s Voy. 1839, 24, pl. ix. Picus rubricatus, Wagler, Isis, 1829, V, May, 516. (“Lichtenstein Mus. Berol.”) Colaptes rubricatus, Bon. Pr. Zoöl. Soc. V, 1837, 108.—Ib. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 114. ? Picus cafer, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 431.—Lath. Index Ornith. II, 1790, 242. ? Picus lathami, Wagler, Syst. 1827, No. 85 (Cape of Good Hope?).