полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

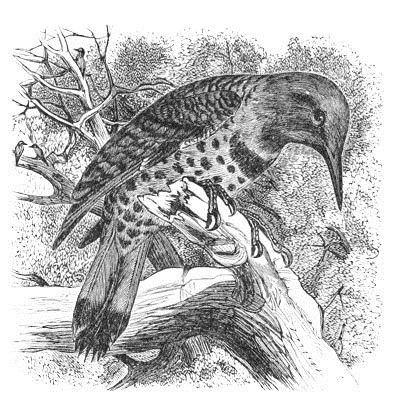

Sp. Char. Shafts and under surfaces of wing and tail feathers orange-red. Male with a red patch on each side the cheek; nape without red crescent; sometimes very faint indications laterally. Throat and stripe beneath the eye bluish-ash. Back glossed with purplish-brown. Female without the red cheek-patch. Length, about 13.00; wing, over 6.50.

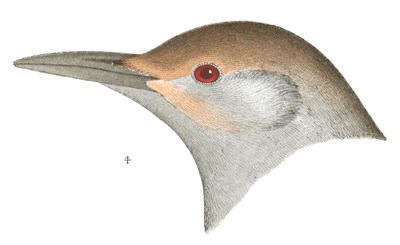

Colaptes mexicanus.

Additional Characters. Spots on the belly, a crescent on the breast, and interrupted transverse bands on the back, black.

Hab. Western North America from Pacific to the Black Hills; north to Sitka on the coast. Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. P. Z. S. 1858, 305); Vera Cruz, alpine regions (Sumichrast, Mem. Bost. Soc. I, 1869. 562); San Antonio, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865. 470); W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 56).

The female is similar in every way, perhaps a little smaller, but lacks the red mustache. This is, however, indicated by a brown tinge over an area corresponding with that of the red of the male.

In the present specimen (1,886) there is a slight indication of an interrupted nuchal red band, as in the common Flicker, in some crimson fibres to some of the feathers about as far behind the eye as this is from the bill. A large proportion of males before us exhibit the same characteristic, some more, some less, although it generally requires careful examination for its detection. It may possibly be a characteristic of the not fully mature bird, although it occurs in two out of three male specimens.

There is a little variation in the size of the pectoral crescent and spots; the latter are sometimes rounded or oblong cordate, instead of circular. The bill varies as much as three or four tenths of an inch. The rump, usually immaculate, sometimes has a few black streaks. The extent of the red whisker varies a little. In skins from Oregon and Washington the color of the back is as described; in those from California and New Mexico it is of a grayer cast. There is little, if any, variation in the shade of red in the whiskers and quill-feathers. The head is washed on the forehead with rufous, passing into ashy on the nape.

There is not only some difference in the size of this species, in the same locality, but, as a general rule, the more southern specimens are smaller.

This species is distinct from the C. mexicanoides of Lafresnaye, though somewhat resembling it. It is, however, a smaller bird; the red of the cheeks is deeper; the whole upper part of the head and neck uniform reddish-cinnamon without any ash, in marked contrast to that on the sides of the head. The back is strongly glossed with reddish-brown, and the black transverse bars are much more distinct, closer and broader, three or four on each feather, instead of two only. The rump and upper tail-coverts are closely barred, the centre of the former only clearer white, but even here each feather has a cordate spot of white. The spots on the flanks posteriorly exhibit a tendency to become transverse bars.

Specimens from Mount Orizaba, Mexico, are very similar to those from Oregon in color, presenting no appreciable difference. The size is, however, much less, a male measuring 10.50, wing 6.00, tail 4.60 inches, instead of 12.75, 6.75, and 5.25 respectively. While, however, the feet are smaller (tarsus 1.00 instead of 1.15), the bill is fully as large, or even larger.

Most young birds of this species have a tinge of red on top of the head, and frequently a decided nuchal crescent of red; but these are only embryonic features, and disappear with maturity.

Habits. This species, the counterpart in so many respects of the Golden-winged Woodpecker, appears to take the place of that species from the slopes of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific, throughout western North America. Dr. Woodhouse speaks of finding it abundant along the banks of the Rio Grande. And in the fine collection belonging to the Smithsonian Institution are specimens from the Straits of Fuca, Fort Steilacoom, and Fort Vancouver, in Washington Territory, from the Columbia River, from various points in California, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Kansas, Nebraska, Texas, Mexico, etc. Dr. Gambel, in his Paper on the birds of California, first met with the Red-shafted Woodpecker soon after leaving New Mexico, and it continued to California, where he found it very abundant. He describes it as a remarkably shy bird, and adds that he always saw it on the margins of small creeks, where nothing grew larger than a willow-bush. Dr. Heermann also found it abundant in California. Dr. Newberry, in his Report on the zoölogy of Lieutenant Williamson’s expedition, speaks of the Red-shafted Flicker as rather a common bird in all parts of California and Oregon which his party visited. He describes many of its habits as identical with those of the Golden Flicker (C. auratus), but regards it as much the shyer bird. Dr. Cooper also mentions the fact of the great abundance of this bird along the western coast, equalling that of its closely allied cousin on the eastern side of the Mississippi. It also resembles, he adds, that bird so exactly in habits and notes that the description of one will apply with exactness to the other. It is a constant resident in Washington Territory, or at least west of the Cascade Mountains. He observed it already burrowing out holes for its nests in April, at the Straits of Fuca. About June 1 he found a nest containing seven young, nearly fledged, which already showed in the male the distinguishing red mustache. Dr. Suckley, in the same report, also says that it is extremely common in the timbered districts of Washington Territory, and adds that its habits, voice, calls, etc., are precisely similar to those of the Yellow-Hammer of the Eastern States. Mr. Nuttall, as quoted by Mr. Audubon, states that he first came upon this bird in the narrow belt of forest which borders Laramie’s Fork of the Platte, and adds that he scarcely lost sight of it from that time until he reached the shores of the Pacific. Its manners, in all respects, are so entirely similar to those of the common species that the same description applies to both. He also regards it as the shyer bird of the two, and less frequently seen on the ground. They burrow in the oak and pine trees, and lay white eggs, after the manner of the whole family, and these eggs are in no wise distinguishable from those of the Golden-wing.

Dr. Cooper, in his Report upon the birds of California, refers to this as a common species, and found in every part of the State except the bare plains. It even frequents the low bushes, where no trees are to be seen for miles. In the middle wooded districts, and towards the north, it is much more abundant than elsewhere.

Their nesting-holes are at all heights from the ground, and are usually about one foot in depth. In the southern part of the State their eggs are laid in April, but farther north, at the Columbia, in May.

Dr. Cooper attributes their shyness in certain localities to their being hunted so much by the Indians for their bright feathers. Generally he found them quite tame, so that their interesting habits may be watched without difficulty. He regards them as an exact counterpart of the eastern auratus, living largely on insects and ants, which they collect without much trouble, and do not depend upon hard work, like other Woodpeckers, for their food. During the season they also feed largely on berries. Their curved bill is not well adapted for hammering sound wood for insects, and they only dig into decayed trees in search of their food. Like the eastern species, the young of these birds, when their nest is approached, make a curious hissing noise. They may be seen chasing each other round the trunk of trees, as if in sport, uttering, at the same time, loud cries like whittoo, whittoo, whittoo. Dr. Kennerly found these birds from the Big Sandy to the Great Colorado, but they were so shy that he could not obtain a specimen. They were seen on the barren hills among the large cacti, in which they nest. Their extreme shyness was fully explained afterwards by finding how closely they are hunted by the Indians for the sake of their feathers, of which head-dresses are made.

Mr. Dresser states that this bird is found as far east as San Antonio, where, however, it is of uncommon occurrence. In December he noticed several near the Nueces River, and in February and March obtained others near Piedras Negras.

Dr. Coues gives it as abundant and resident in Arizona, where it is found in all situations. Its tongue, he states, is capable of protrusion to an extent far beyond that of any other North American Woodpecker.

This bird, in some parts of California, is known as the Yellow-Hammer, a name given in some parts of New England to the Colaptes auratus. Mr. C. W. Plass, of Napa City, writes me that this Woodpecker “makes himself too much at home with us to be agreeable. He drills large holes though the weather-boards of the house, and shelters himself at night between them and the inner wall. He does, not nest there, but simply makes of such situations his winter home. We have had to shoot them, for we find it is of no use to shut up one hole, as they will at once make another by its side.”

Mr. J. A. Allen mentions finding this species, in the absence of suitable trees on the Plains, making excavations in sand-banks.

According to Mr. Ridgway, the Red-shafted Flicker does not differ from the Yellow-shafted species of the east in the slightest particular, as regards habits, manners, and notes. It is, however, more shy than the eastern species, probably from the fact that it is pursued by the Indians, who prize its quill and tail-feathers as ornaments with which to adorn their dress.

Their eggs are hardly distinguishable from those of the auratus, but range of a very slightly superior size. They average 1.12 inches in length by .89 of an inch in breadth. Their greatest length is 1.15 inches, their least 1.10, and their breadth ranges from .87 to .90.

Colaptes hybridus, BairdHYBRID FLICKERColaptes ayresii, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, 348, pl. ccccxciv. Colaptes hybridus, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 122. Colaptes mexicanus, Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 422 (mixed with mexicanus). Picas hybridus aurato-mexicanus, Sundevall, Consp. Pic. 1866, 721.

Sp. Char. Yellow shafts or feathers on wing and tail combined with red, or red spotted cheek-patches. Orange-red shafts combined with a well-defined nuchal red crescent, and pinkish throat. Ash-colored throat combined with black cheek-patch or yellow shafts. Shafts and feathers intermediate between gamboge-yellow and dark orange-red.

Hab. Upper Missouri and Yellowstone; Black Hills.

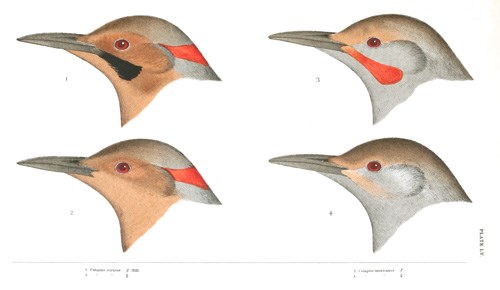

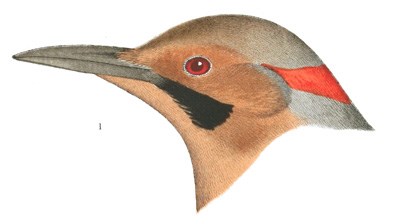

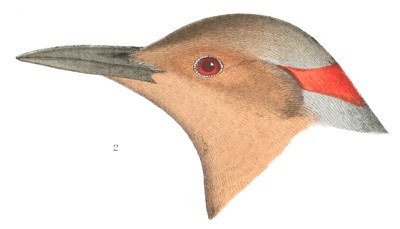

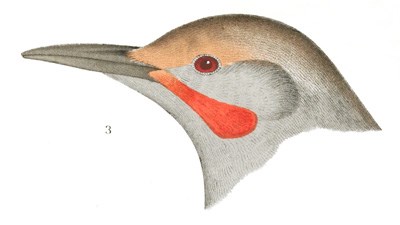

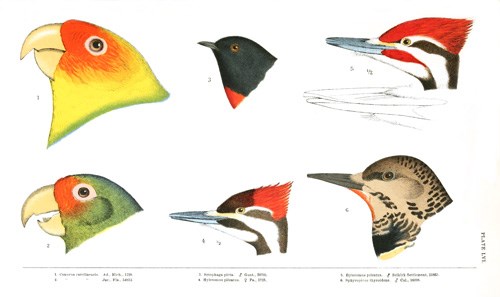

PLATE LV.

1. Colaptes auratus. ♂ 2122.

2. Colaptes auratus. ♀.

3. Colaptes mexicanus. ♂.

4. Colaptes mexicanus. ♀.

The general distribution of Colaptes mexicanus, as already indicated, is from the Pacific coast of the United States, eastward to the Black Hills and the Upper Missouri and Yellowstone; that of the C. auratus from the Atlantic Coast to about the eastern limits of mexicanus. But little variation is seen in the two species up to the region mentioned; slight differences in shade of color, size, and frequency of spots, etc., being all. Where they come together, however, or overlap, a most remarkable race is seen, in which no two specimens, nay, scarcely the two sides of the same bird, are alike, the characters of the two species becoming mixed up in the most extraordinary manner. Thus, the shafts show every shade from orange-red to pure yellow; yellow shafts combine with red cheek-patch (as in C. ayresii of Audubon); a red nape, with orange-red shafts; cheek-patches red with black feathers intermixed, or vice versa; perhaps the feathers red at base and black at tip, or black at base and red at tip, etc. As the subject has been presented in sufficient detail in the Birds of North America, as quoted above, it need not be repeated here, except to say that collections received since 1858 only substantiate what has there been stated.

To the race thus noted, the name hybridus was given, not as of a variety, since it is not entitled to this rank, but as of a heterogeneous mixture, caused by the breeding together of two different species, and requiring some appellation. Whether the presumed hybrids are fertile, and breed with each other or with full-blooded parents, has not yet been ascertained; perhaps not, since the area in which they occur is limited, and it is only occasionally that individuals of the kind referred to have been found beyond the bounds mentioned. It is very rarely, however, that pure breeds occur in the district of hybridus, a taint being generally appreciable in all.

The conditions in the present instance appear different from those adverted to under the head of Picus villosus, where the question is not one of hybridism between two strongly marked and distinct species, but of the gradual change, between the Atlantic and the Pacific, from one pattern of coloration to another.

Colaptes chrysoides, MalhTHE CAPE FLICKERGeopicus chrysoides, Malh. Rev. et Mag. Zoöl. IV, 1852, 553.—Ib. Mon. Pic. II, 261, tab. 109. Colaptes chrysoides, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 125.—Elliot, Ill. Birds N. Am. VI, plate.—Cooper, Pr. Cal. Ac. 1861, 122 (Fort Mohave).—Coues, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1866, 56 (Arizona).—Scl. Cat. 1862, 344.—Elliot, Illust. Am. B. I, pl. xxvi.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 410. Picus chrysoides, Sundevall, Consp. 72.

Sp. Char. Markings generally as in other species. Top of head rufous-brown; chin, throat, and sides of head ash-gray. Shafts of quills and tail-feathers, with their under surfaces in great part, gamboge-yellow; no nuchal red. Malar patch of male red; wanting in the female. Length, 11.50; wing, 5.75; tail, 4.50.

Hab. Colorado and Gila River, north to Fort Mohave, south to Cape St. Lucas. Localities: Fort Mohave (Cooper, Pr. Cal. Ac. 1861, 122); W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 56).

This interesting species is intermediate between auratus and mexicanus in having the yellow shafts and quills of the former; a red malar patch, an ashy throat, and no nuchal crescent, as in the latter. To mexicanoides the relationship is still closer, since both have the rufous-brown head above. A hybrid between this last species and auratus would in some varieties come very near chrysoides, but as it does not belong to the region of chrysoides, and there is no transition from one species to the other in any specimens, as in hybridus, there is no occasion to take this view of the species.

Cape St. Lucas specimens, where the species is exceedingly abundant, are considerably smaller than those from Arizona, and appear to be more strongly marked with black above and below; otherwise there seems to be no difference of special importance.

As neither C. auratus nor mexicanus has the top of the head rufous-brown, (though slightly indicated anteriorly in the latter), this character has not been noted in the hybrids between the two (hybridus), and its presence in chrysoides will serve to distinguish it from hybridus.

Habits. This comparatively new form of Woodpecker was first described in 1852 by Malherbe, from a California specimen in the Paris Museum, which had been at first supposed to be a female or immature ayresii. What Dr. Cooper thinks may have been this species was met with by Dr. Heermann among the mountains bordering upon the Cosumnes River, in California, where it was rare, and only two specimens were taken. In February, 1861, other specimens of this bird were taken at Fort Mohave by Dr. Cooper. They were feeding on larvæ and insects among the poplar-trees, and were very shy and wary. The bird is supposed to winter in the Colorado Valley, and wherever found has been met with in valleys, and not on mountains. It is an abundant and characteristic member of the Cape St. Lucas fauna.

According to Dr. Cooper these birds were already mated at Fort Mohave after February 20. They had the same habits, flight, and cries as the C. mexicanus. They appeared to be migratory, having come from the south.

Mr. Xantus, in his brief notes on the birds of Cape St. Lucas, makes mention of finding this bird breeding, May 19, in a dead Cereus giganteus. The nest was a large cavity about fifteen feet from the ground, and contained only one egg. The parent bird was also secured. In another instance two eggs were found in a Cereus giganteus, at the distance of forty feet from the ground. The eggs were not noticeably different from those of the common Colaptes mexicanus.

Family PSITTACIDÆ.—The Parrots

Char. Bill greatly hooked; the maxilla movable and with a cere at the base. Nostrils in the base of the bill. Feet scansorial, covered with granulated scales.

The above diagnosis characterizes briefly a family of the Zygodactyli having representatives throughout the greater part of the world, except Europe, and embracing about three hundred and fifty species, according to the late enumeration of Finsch,136 of which one hundred and forty-two, or nearly one half, are American (seventy Brazilian alone). The subfamilies are as follows:—

I. Stringopinæ. Appearance owl-like; face somewhat veiled or with a facial disk, as in the Owls.

II. Plyctolophinæ. Head with an erectile crest, of variable shape.

III. Sittacinæ. Head plain. Tail long, or lengthened, wedge-shaped or graduated.

IV. Psittacinæ. Head plain. Tail short or moderate, straight or rounded.

V. Trichoglossinæ. Tip of tongue papillose. Bill compressed; tip of maxilla internally smooth, not crenate; gonys obliquely ascending.

Of these, Nos. III and IV alone are represented in the New World, and only the Sittacinæ occur in the United States, with one species.

Subfamily SITTACINÆ

The lengthened cuneate tail, as already stated, distinguishes this group from the American Psittacinæ with short, square, or rounded tail. The genera are distinguished as follows:—

Sittace. Culmen flattened. Face naked, except in S. pachyrhyncha. Tail as long as or longer than wings.

Conurus. Culmen rounded. Face entirely feathered, except a curve around the eye. Tail shorter than wings.

Of the genus Sittace, which embraces eighteen species, two come sufficiently near to the southern borders of the United States to render it not impossible that they may yet be found to cross the border. Of one of these, indeed, (S. pachyrhyncha,) there is a specimen in the Museum of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, presented by J. W. Audubon as shot on the Rio Grande of Texas; and another (S. militaris) is common at Mazatlan, and perhaps even at Guaymas. There is considerable reason for doubt as to the authenticity of the alleged locality of the S. pachyrhyncha, but for the purpose of identification, should either species present itself, we give diagnoses in the accompanying foot-note.137

Genus CONURUS, KuhlConurus, Kuhl, Consp. Psittac. 4, 1830.—Ib. Nova Acta K. L. C. Acad. X, 1830.

Gen. Char. Tail long, conical, and pointed; bill stout; cheeks feathered, but in some species leaving a naked ring round the eye; cere feathered to the base of the bill.

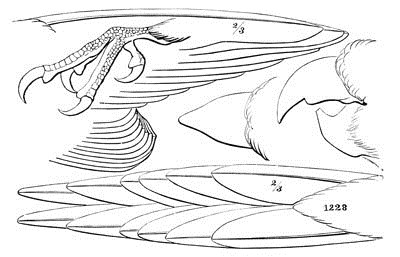

Conurus carolinensis.

1228

The preceding diagnosis, though not very full, will serve to indicate the essential characteristics of the genus among the Middle American forms with long pointed tails, the most prominent feature consisting in the densely feathered, not naked, cheeks. But one species belongs to the United States, though three others are found in Mexico, and many more in South and Central America. A few species occur in the West Indies.

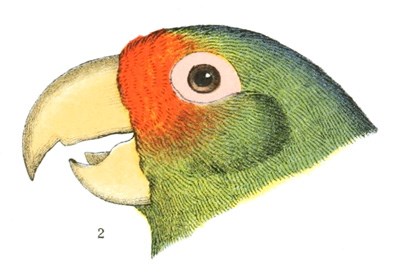

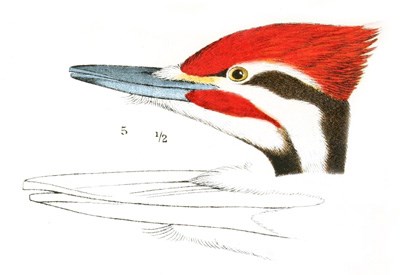

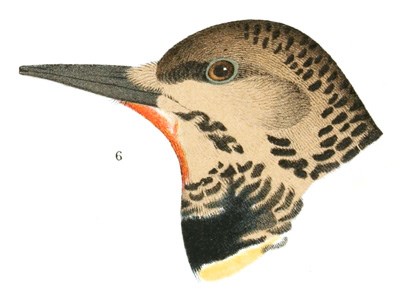

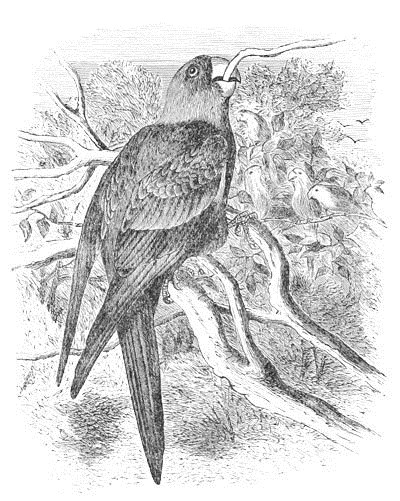

PLATE LVI.

1. Conurus carolinensis. Ad., Mich., 1228.

2. Conurus carolinensis. Juv., Fla., 54812.

3. Setophaga picta. ♂ Guat., 30705.

4. Hylotomus pileatus. ♀ Pa., 1723.

5. Hylotomus pileatus. ♂ Selkirk Settlement, 51863.

6. Sphyropicus thyroideus. ♂ Cal., 16098.

Conurus carolinensis, KuhlPARAKEET; CAROLINA PARROT; ILLINOIS PARROT

Psittaca carolinensis, Brisson, Ornith. II, 1762, 138. Psittacus carolinensis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1758, 97; 1766, 141 (nec Scopoli).—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 89, pl. xxvi, fig. 1.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 135, pl. xxvi. Conurus carolinensis, Kuhl, Nova Acta K. L. C. 1830.—Bon. List, 1838.—Pr. Max. Cabanis Journ. für Orn. V, March, 1857, 97.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 57.—Finsch, Papagei. I, 1857, 478.—Scl. Cat. 1862, 347.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 308. Centurus carolinensis, Aud. Syn. 1839, 189.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 306, pl. cclxxviii. Psittacus ludovicianus, Gm. Syst. I, 1788, 347. Psittacus thalassinus, Vieill. Ency. Meth. 1377. Conurus ludovicianus, Gray. Catal. Br. Mus. Psittac. 1859, 36 (makes distinct species from carolinensis). Carolina parrot, Catesby, Car. I, tab. xi.—Latham, Syn. I, 227.—Pennant, II, 242. Orange-headed parrot, Latham, Syn. I, 304.

Conurus carolinensis.

Sp. Char. Head and neck all round gamboge-yellow; the forehead, from above the eyes, with the sides of the head, pale brick-red. Body generally with tail green, with a yellowish tinge beneath. Outer webs of primaries bluish-green, yellow at the base; secondary coverts edged with yellowish. Edge of wing yellow, tinged with red; tibiæ yellow. Bill white. Legs flesh-color. Length, about 13.00; wing, 7.50; tail, 7.10. Young with head and neck green. Female with head and neck green; the forehead, lores, and suffusion round the eyes, dark red, and without the yellow of tibiæ and edge of wing. Size considerably less.

Hab. Southern and Southwestern States and Mississippi Valley; north to the Great Lakes and Wisconsin.

This species was once very abundant in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, being known throughout the Southern States, and the entire valley of the Mississippi, north to the Great Lakes. Stragglers even penetrated to Pennsylvania, and one case of their reaching Albany, N. Y., is on record. Now, however, they are greatly restricted. In Florida they are yet abundant, but, according to Dr. Coues, they are scarcely entitled to a place in the fauna of South Carolina. In Western Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory, they are still found in considerable numbers, straggling over the adjacent States, but now seldom go north of the mouth of the Ohio. We have seen no note of their occurrence south of the United States, and in view of their very limited area and rapid diminution in numbers, there is little doubt but that their total extinction is only a matter of years, perhaps to be consummated within the lifetime of persons now living. It is a question whether both sexes are similarly colored, as in most American Parrots, or whether the female, as just stated, lacks the yellow of the head. Several female birds killed in Florida in March agree in the characters indicated above for that sex; but the material at our command is not sufficient to decide whether all females are similarly marked, or whether the plumage described is that of the bird of the second year generally. There is no trace whatever of yellow on the head.