полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Dr. Gambel first observed this Woodpecker in a belt of oak timber near the Mission of St. Gabriel, in California, and states that it was abundant. He also describes its habits as peculiar, and unlike the generality of Woodpeckers. Dr. Heermann, too, speaks of finding it in all the parts of California which he visited. Dr. Newberry, in his Notes on the zoölogy of Lieutenant Williamson’s expedition, refers to it as most unlike the California Woodpecker in the region it occupies and in its retiring habits. He describes it as seeming to choose, for its favorite haunts, the evergreen forests upon the rocky declivities of the Cascade and Rocky Mountains. He first observed it in Northern California, but subsequently noticed it in the mountains all the way to the Columbia. Though often seen in low elevations, it was evidently alpine in its preferences, and was found most frequently near the line of perpetual snow; and when crossing the snow lines, in the mountain-passes, it was often observed flying far above the party. He describes it as being always shy, and difficult to shoot.

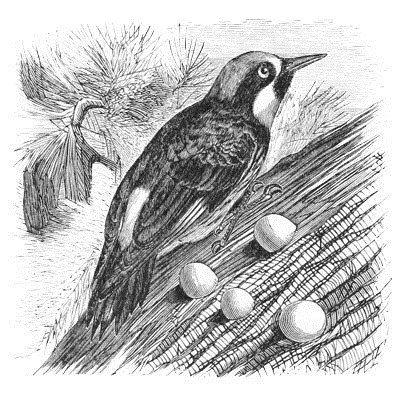

Dr. S. W. Woodhouse describes this species as being common in the Indian Territory and in New Mexico; while Dr. Cooper, in his Report on the zoölogy of Washington Territory, speaks of it as being common, during summer, in all the interior districts, but seldom or never approaching the coast. It arrives at Puget Sound early in May, and some even remain, during mild winters, in the Territory. According to his account, it burrows holes for its nests at all heights from the ground, but commonly in dead trees. The eggs are described as pure white, and, when fresh, translucent, like those of all the Woodpecker tribe, and hardly distinguishable in size and general appearance from those of the Golden-winged Woodpecker (Colaptes auratus). Its harsh call is rarely uttered in summer, when it seems to seek concealment for itself and nest. The flocks of young, which in fall associate together to the number of eight or ten, are more noisy. Dr. Suckley, in the same Report (page 162), speaks of this Woodpecker as being very abundant throughout the more open portions of the timbered region of the northwest coast, preferring oak openings and groves. At Fort Dalles, on the Columbia, they are extremely numerous, not only breeding there during summer, but also found as winter residents. Their breeding-places are generally holes in oak and other trees, which, from the appearance of all he examined, seemed to have been excavated for the purpose. At Puget Sound this species was found less frequently than at Fort Dalles, on the Columbia. At the latter place they were constant winter residents. Dr. Suckley also speaks of them as being semi-gregarious in their habits.

Mr. Lord thinks that this Woodpecker is not to be met with west of the Cascade Mountains, but says it is very often found between the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains, where it frequents the open timber. The habits and modes of flight of this bird, he states, are not the least like a Woodpecker’s. It flies with a heavy flapping motion, much like a Jay, feeds a good deal on the ground, and chases insects on the wing like a Shrike or a Kingbird. Whilst mating they assemble in large numbers, and keep up a continual, loud, chattering noise. They arrive at Colville in April, begin nesting in May, and leave again in October. The nest is in a hole in a dead pine-tree, usually at a considerable height from the ground.

Dr. Coues says this bird is very common at Fort Whipple, in Arizona, where it remained in moult until November.

Mr. J. A. Allen found this the most numerous of the Picidæ in Colorado Territory. He also states that it differs considerably in its habits from all the other Woodpeckers. He frequently noticed it rising high into the air almost vertically, and to a great height, apparently in pursuit of insects, and descending again as abruptly, to repeat the same manœuvre. It was met with by Mr. Ridgway in the Sacramento Valley, along the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada, and in the East Humboldt Mountains. In the first-mentioned locality it was the most abundant Woodpecker, and inhabited the scattered oaks of the plains. In the second region it was very abundant—perhaps more so than any other species—among the scattered pines along the very base of the eastern slope; and in the last-mentioned place was observed on a few occasions among the tall aspens bordering the streams in the lower portions of the cañons. In its habits it is described as approaching most closely to our common Red-headed Woodpecker (M. erythrocephalus), but possessing many very distinctive peculiarities. In the character of its notes it quite closely approximates to our common Redhead, but they are weaker and of a more twittering character; and in its lively playful disposition it even exceeds it. It has a very peculiar and characteristic habit of ascending high into the air, and taking a strange, floating flight, seemingly laborious, as if struggling against the wind, and then descending in broad circles to the trees.

The eggs are more spherical than are usually those of the Colaptes auratus, are of a beautiful crystalline whiteness, and measure 1.10 inches in length and .92 of an inch in breadth.

Melanerpes erythrocephalus, SwainsonRED-HEADED WOODPECKERPicus erythrocephalus, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 174.—Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 60, pl. cxii, cxiii.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, 1810, 142, pl. ix, fig. 1.—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 14.—Ib. Isis, 1829, 518 (young).—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 141; V, 536, pl. xxvii.—Ib. Birds America, IV, 1842, 274, pl. cclxxi.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 419. Melanerpes erythrocephalus, Sw. F. B. A. II, 1831, 316.—Bon. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, 1850, 115.—Gambel, J. Ac. Nat. Sc. Ph. 2d ser. I, 1847, 55.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 113.—Scl. Cat. 1862, 340.—Samuels, 102.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 402.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 307. Picus obscurus, Gm. I, 1788, 429 (young).—Red-headed Woodpecker, Pennant, Kalm, Latham. White-rumped Woodpecker, Latham.

Sp. Char. Head and neck all round crimson-red, margined by a narrow crescent of black on the upper part of the breast. Back, primary quills, and tail bluish-black. Under parts generally, a broad band across the middle of the wing, and the rump, white. The female is not different. Length, about 9.75; wing, 5.50. Bill bluish-white, darker terminally; iris chestnut; feet olive-gray. Young without any red, the head and neck being grayish streaked with dusky; breast with an ashy tinge, and streaked sparsely with dusky; secondaries with two or three bands of black; dorsal region clouded with grayish.

Hab. Eastern Province of United States to base of Rocky Mountains, sometimes straggling westward to coast of California (Gambel). Salt Lake City, Utah (Ridgway). Other localities: Nueces to Brazos, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 469, breeds).

Western specimens frequently have the abdomen strongly tinged with salmon-red, or orange-red, and are generally more deeply colored than eastern.

Habits. The Red-headed Woodpecker is one of the most familiar birds of this family, and ranges over a wide extent of territory. Excepting where it has been exterminated by the persecutions of indiscriminate destroyers, it is everywhere a very abundant species. Once common, it is now rarely met with in the neighborhood of Boston, though in the western part of Massachusetts it is still to be found. In the collections of the Smithsonian Institution are specimens from Pennsylvania, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Louisiana, the Indian Territory, etc. Sir John Richardson speaks of it as ranging in summer as far north as the northern shores of Lake Huron. He also remarks that in the Hudson Bay Museum there is a specimen from the banks of the Columbia River. Dr. Gambel, in his paper on the birds of California, states that he saw many of them in a belt of oak timber near the Mission of St. Gabriel. As, however, Dr. Heermann did not meet with it in California, and as no other collector has obtained specimens in that State, this is probably a mistake. With the exception of Dr. Woodhouse, who speaks of having found this species in the Indian Territory and in Texas, it is not mentioned by any of the government exploring parties. It may therefore be assigned a range extending, in summer, as far north as Labrador, and westward to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. Throughout the year it is a permanent resident only of the more southern States, where it is, however, much less abundant in summer than it is in Pennsylvania.

Wilson, at the time of his writing (1808), speaks of finding several of the nests of this Woodpecker within the boundaries of the then city of Philadelphia, two of them being in buttonwood-trees and one in the decayed limb of an elm. The parent birds made regular excursions to the woods beyond the Schuylkill, and preserved a silence and circumspection in visiting their nest entirely unlike their habits in their wilder places of residence. The species is altogether migratory, visiting the Middle and Northern States early in May and leaving in October. It begins the construction of its nest almost immediately after its first appearance, as with other members of its family, by excavations made in the trunk or larger limbs of trees, depositing six white eggs on the bare wood. The cavities for their nests are made almost exclusively in dead wood, rarely, if ever, in the living portion of the tree. In Texas, Louisiana, Kentucky, and the Carolinas, they have two broods in a season, but farther north than this they rarely raise more than one. Their eggs are usually six in number, and, like all the eggs of this family, are pure white and translucent when fresh. They vary a little in their shape, but are usually slightly more oval and less spherical than those of several other species. Mr. Nuttall speaks of the eggs of this bird as being said to be marked at the larger end with reddish spots. I have never met with any thus marked, and as Mr. Nuttall does not give it as from his own observations I have no doubt that it is a mistake. Mr. Paine, of Randolph, Vt., writes that he has only seen a single specimen of this Woodpecker in that part of Vermont, while on the western side of the Green Mountains they are said to be very common. He adds that it is a tradition among his older neighbors that these Woodpeckers were formerly everywhere known throughout all portions of the State.

Mr. Ridgway saw a single individual of this species in the outskirts of Salt Lake City, in July, 1869.

Their eggs vary both in size and in shape, from a spherical to an oblong-oval, the latter being the more usual. Their length varies from 1.10 to 1.15 inches, and their breadth from .80 to .90 of an inch.

Melanerpes formicivorus, var. formicivorus, BonapCALIFORNIA WOODPECKERPicus formicivorus, Swainson, Birds Mex. in Philos. Mag. I, 1827, 439 (Mexico).—Vigors, Zoöl. Blossom, 1839, 23 (Monterey).—Nuttall, Man. I, 2d ed. 1840. Melanerpes formicivorus, Bp. Conspectus, 1850, 115.—Heermann, J. A. N. Sc. Phil. 2d series, II, 1853, 270.—Cassin, Illust. II, 1853, 11, pl. ii.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Oregon Route, 90, P. R. R. Surv. VI, 1857.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1868, 114.—Sumichrast, Mem. Bost. Soc. I, 1865, 562 (correcting an error of Saussure).—Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 63, 328.—Heermann, P. R. R. X, 58 (nesting).—Baird, Rep. M. Bound. II, Birds, 6.—Sclater, Pr. Z. S. 1858, 305 (Oaxaca).—Ib. Ibis, 137 (Honduras).—Cab. Jour. 1862, 322 (Costa Rica).—Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 55.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 403. Picus melanopogon, Temminck, Pl. Color. IV, (1829? pl. ccccli.—Wagler, Isis, 1829, v, 515.—Sundevall, Consp. 51.

Melanerpes formicivorus.

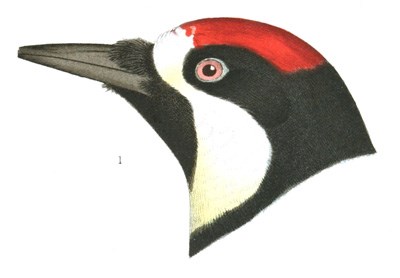

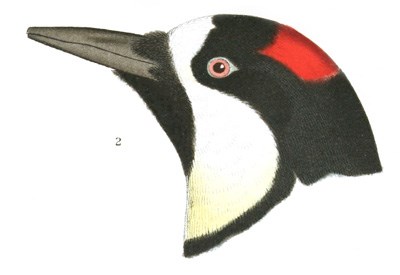

Sp. Char. Fourth quill longest, third a little shorter. Above and on the anterior half of the body, glossy bluish or greenish black; the top of the head and a short occipital crest red. A white patch on the forehead, connecting with a broad crescentic collar on the upper part of the neck by a narrow isthmus, white tinged with sulphur-yellow. Belly, rump, bases of primaries, and inner edges of the outer quills, white. Tail-feathers uniform black. Female with the red confined to the occipital crest, the rest replaced by greenish-black; the three patches white, black, and red, very sharply defined, and about equal. Length about 9.50; wing, 6.00; tail, 3.75.

Hab. Pacific Coast region of the United States and south; in Northern Mexico, eastward almost to the Gulf of Mexico; also on the Upper Rio Grande; south to Costa Rica. Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. P. Z. S. 1858, 305); Cordova (Scl. 1856, 307); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 137); Honduras (Scl. Cat. 341); Costa Rica (Cab. J. 1862, 322); W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 55).

In most specimens one or two red feathers may be detected in the black of the breast just behind the sulphur-yellow crescent. The white of the breast is streaked with black; the posterior portion of the black of the breast and anterior belly streaked with white. The white of the wing only shows externally as a patch at the base of the primaries.

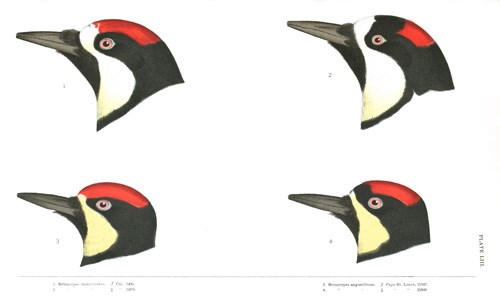

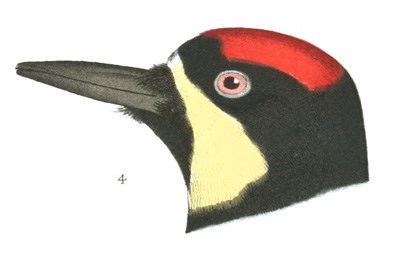

PLATE LIII.

1. Melanerpes formicivorus. ♂ Cal., 5495.

2. Melanerpes formicivorus. ♀ Cal., 25035.

3. Melanerpes angustifrons. ♂ Cape St. Lucas, 25947.

4. Melanerpes angustifrons. ♀ Cape St. Lucas, 25949.

Dr. Coues calls attention to extraordinary differences in the color of the iris, which varies from white to red, blue, yellow, ochraceous, or brown. A mixture of blue, he thinks, indicates immaturity, and a reddish tinge the full spring coloration.

The male of this species has a white forehead extending a little backwards of the anterior edge of the eye, the rest of the top of head to the nape being red. The female has the white forehead, and a quadrate occipito-nuchal red patch, a black band about as broad as the white one separating the latter from the occipital red. The length of the two anterior bands together is decidedly greater than that of the posterior red. In both sexes the jugulum is entirely and continuously black. Anteriorly (generally with a red spot in its anterior edge) and on the feathers of its posterior border only are these elongated white spots, on each side the shaft, the feathers of the breast being streaked centrally with black. The inner webs of the secondaries have an elongated continuous patch of white along their internal edge, with a very slight, almost inappreciable, border of black; this white only very rarely converted partly or entirely into quadrate spots, and that never on the innermost quills marked with white. Specimens from California are very similar to those from the Rocky Mountains and the Rio Grande Valley, except, perhaps, in being larger, with longer and straighter bill.

In M. flavigula from Bogota, the male has the head marked with the red, black, and white (the red much less in extent, however) of the female M. formicivorus, while the female has no red whatever. All, or nearly all, the feathers of the jugulum have the two white spots, and (as pointed out by Reichenbach) the white of the inner webs of the inner quills is entirely converted into a series of non-confluent quadrate spots. The black streaks on the sides and behind appear to be of greater magnitude, and more uniformly distributed. In both species all the tail-feathers are perfectly black.

A Guatemalan bird, received from Mr. Salvin as M. formicivorus,—and indeed all specimens from Orizaba and Mirador to Costa Rica,—agrees in the main with the northern bird, except that all the black feathers of the jugulum have white spots, as in M. flavigula. The outermost tail-feather of Mr. Salvin’s specimen has two narrow transverse whitish bands, and a spot indicating a third, as well as a light tip. The white markings on the inner quills are more like the northern bird, though on the outermost ones there is the same tendency to form spots as in a few northern specimens (as 6,149 from Los Nogales, &c.). The bill is very different from either in being shorter, broader, much stouter, and the culmen more decurved.

These peculiarities, which are constant, appear to indicate a decided or strongly marked variety, as a series of almost a hundred specimens of the northern bird from many localities exhibit none of the characters mentioned, while all of an equally large series from Central America agree in possessing them.

A series of Jalapan specimens from the cabinet of Mr. Lawrence show a close relationship to skins from the Rio Grande, and do not approach the Guatemalan bird in the peculiar characters just referred to, except in the shortness and curvature of the bill. In one specimen there is an approach to the Bogotan in a moderate degree of barring on the white inner edgings of the tertials; in the rest, however, they are continuously white.

Habits. This handsome Woodpecker, distinguished both by the remarkable beauty of its plumage and the peculiarity of its provident habits, has a widely extended area of distribution, covering the Pacific Coast, from Oregon throughout Mexico. In Central America it is replaced by the variety striatipectus, and in New Grenada by the var. flavigula, while at Cape St. Lucas we find another local form, M. angustifrons. So far as we have the means of ascertaining their habits, we find no mention of any essential differences in this respect among these races.

Suckley and Cooper did not meet with this bird in Washington Territory, and Mr. Lord met with it in abundance on his journey from Yreka to the boundary line of British Columbia. Mr. Dresser did not observe it at San Antonio. Mr. Clark met with it at the Coppermines, in New Mexico, in great numbers, and feeding principally among the oaks. Lieutenant Couch found it in the recesses of the Sierra Madre quite common and very tame, resorting to high trees in search of its food. He did not meet with it east of the Sierra Madre. Dr. Kennerly first observed it in the vicinity of Santa Cruz, where it was very frequent on the mountain-slopes, always preferring the tallest trees, but very shy, and it was with difficulty that a specimen could be procured. Mr. Nuttall, who first added this bird to our fauna, speaks of it as very plentiful in the forests around Santa Barbara. Between that region and the Pueblo de los Angeles, Dr. Gambel met with it in great abundance, although neither writer makes mention of any peculiarities of habit. Mr. Emanuel Samuels met with it in and around Petaluma, where he obtained the eggs.

Dr. Newberry, in his Report on the zoölogy of Lieutenant Williamson’s route (P. R. R. Reports, VI), states that the range of this species extends to the Columbia, and perhaps above, to the westward of the Cascade Range, though more common in California than in Oregon. It was not found in the Des Chutes Basin, nor in the Cascade Mountains.

In the list of the birds of Guatemala given by Mr. Salvin in the Ibis, this Woodpecker is mentioned (I, p. 137) as being found in the Central Region, at Calderas, on the Volcan de Fuego, in forests of evergreen oaks, where it feeds on acorns.

Dr. Heermann describes it as among the noisiest as well as the most abundant of the Woodpeckers of California. He speaks of it as catching insects on the wing, after the manner of a Flycatcher, and mentions its very extraordinary habit of digging small holes in the bark of the pine and the oak, in which it stores acorns for its food in winter. He adds that one of these acorns is placed in each hole, and is so tightly fitted or driven in that it is with difficulty extracted. Thus, the bark of a large pine forty or fifty feet high will present the appearance of being closely studded with brass nails, the heads only being visible. These acorns are thus stored in large quantities, and serve not only the Woodpecker, but trespassers as well. Dr. Heermann speaks of the nest as being excavated in the body of the tree to a depth varying from six inches to two feet, the eggs being four or five in number, and pure white.

These very remarkable and, for a Woodpecker, somewhat anomalous habits, first mentioned among American writers by Dr. Heermann, have given rise to various conflicting statements and theories in regard to the design of these collections of acorns. Some have even ventured to discredit the facts, but these are too well authenticated to be questioned. Too many naturalists whose accuracy cannot be doubted have been eyewitnesses to these performances. Among these is Mr. J. K. Lord, who, however, was constrained to confess his utter inability to explain why the birds did so. He was never able to find an acorn that seemed to have been eaten, nor a trace of vegetable matter in their stomachs, and at the close of his investigations he frankly admitted this storing of acorns to be a mystery for which he could offer no satisfactory explanation.

M. H. de Saussure, the Swiss naturalist, in an interesting paper published in 1858 in the Bibliothèque Universelle of Geneva, furnishes some very interesting observations on the habits of a Woodpecker, which he supposed to be the Colaptes mexicanoides of Mexico, of storing collections of acorns in the hollow stems of the maguay plants. Sumichrast, who accompanied Saussure in his excursion, while recognizing the entire truth of the interesting facts he narrates, is confident that the credit of all this instinctive forethought belongs not to the Colaptes, but to the Mexican race of this species. Saussure’s article being too long to quote in full, we give an abstract.

The slopes of a volcanic mountain, Pizarro, near Perote, in Mexico, are covered with immense beds of the maguay (Agave americana), with larger growths of yuccas, but without any other large shrubs or trees. Saussure was surprised to find this silent and dismal wilderness swarming with Woodpeckers. A circumstance so unusual as this large congregation of birds, by nature so solitary, in a spot so unattractive, prompted him to investigate the mystery. The birds were seen to fly first to the stalks of the maguay, to attack them with their beaks, and then to pass to the yuccas, and there repeat their labors. These stalks, upon examination, were all found to be riddled with holes, placed irregularly one above another, and communicating with the hollow cavity within. On cutting open one of these stalks, he found it filled with acorns.

As is well known, this plant, after flowering, dies, its stalk remains, its outer covering hardens into a flinty texture, and its centre becomes hollow. This convenient cavity is used by the Woodpecker as a storehouse for provisions that are unusual food for the tribe. The central cavity of the stalk is only large enough to receive one acorn at a time. They are packed in, one above the other, until the cavity is full. How did these Woodpeckers first learn to thus use these storehouses, by nature closed against them? The intelligent instinct that enabled this bird to solve this problem Saussure regarded as not the least surprising feature. With its beak it pierces a small round hole through the lower portion into the central cavity, and thrusts in acorns until the hollow is filled to the level of the hole. It then makes a second opening higher up, and fills the space below in a like manner, and so proceeds until the entire stalk is full. Sometimes the space is too small to receive the acorns, and they have to be forced in by blows from its beak. In other stalks there are no cavities, and then the Woodpecker creates one for each acorn, forcing it into the centre of the pith.

The labor necessary to enable the bird to accomplish all this is very considerable, and great industry is required to collect its stores; but, once collected, the storehouse is a very safe and convenient one. Mount Pizarro is in the midst of a barren desert of sand and volcanic débris. There are no oak-trees nearer than the Cordilleras, thirty miles distant, and therefore the collecting and storing of each acorn required a flight of sixty miles.