полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Inner webs of middle tail-feathers unvariegated black. Lower parts dirty ashy-whitish, abdomen dilute gamboge-yellow. Wing, 5.20; tail, 3.60; bill, 1.50. Hab. Eastern Mexico, north to the Rio Grande … var. aurifrons.

Inner webs of middle tail-feathers spotted with white. Lower parts smoky-olive, belly bright orange-yellow. Wing, 4.70; tail, 2.80; bill, 1.16. Hab. Costa Rica … var. hoffmanni.130

C. uropygialis. Middle of the belly yellowish. Nape and forehead soft smoky grayish-brown. Female without red or yellow on head. White of rump and upper tail-coverts with transverse dusky bars. Inner webs of middle tail-feathers spotted with white. Wing, 5.30; tail, 3.70; bill, 1.35. Hab. Western Mexico, north into Colorado, region of Middle Province of United States.

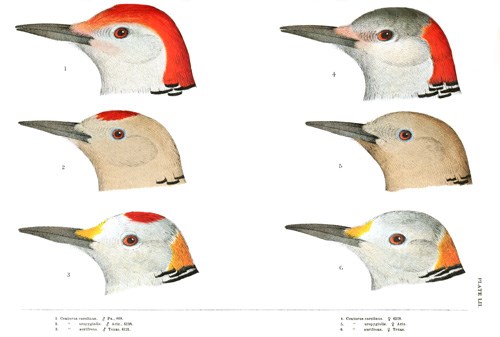

PLATE LII.

1. Centurus carolinus. ♂ Pa., 868.

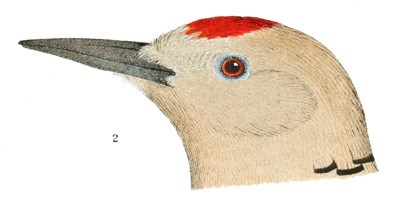

2. Centurus uropygialis. ♂ Ariz., 6128.

3. Centurus aurifrons. ♂ Texas, 6121.

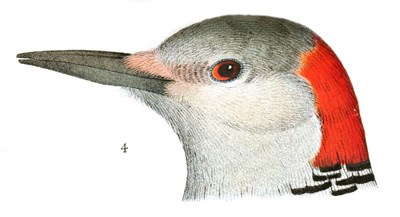

4. Centurus carolinus. ♀ 6118.

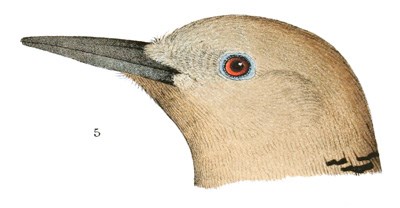

5. Centurus uropygialis. ♀ Ariz.

6. Centurus aurifrons. ♀ Texas.

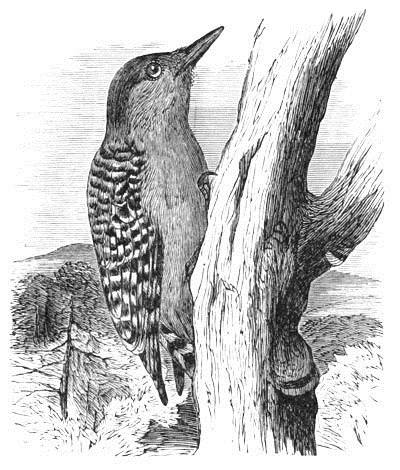

Centurus carolinus, BonapRED-BELLIED WOODPECKER

Picus carolinus, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 174.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, 1808, 113, pl. vii, f. 2.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 169, pl. ccccxv.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 270, pl. cclxx.—Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 418.—Sundevall, Consp. 53. Centurus carolinus, Sw. Bp. List, 1838.—Ib. Conspectus, Av. 1850, 119.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 109.—Cab. Jour. 1862, 324.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 469 (resident in Texas).—Scl. Cat. 1862, 342.—Gray, Cat. 99.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 306. Centurus carolinensis, Sw. Birds, II, 1837, 310 (error). Picus griseus, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 52, pl. cxvi. ? Picus erythrauchen, Wagler, Syst. Avium, 1827. Picus zebra, Boddært, Tabl. pl. enl. (Gray, genera).

Sp. Char. Third, fourth, and fifth quills nearly equal, and longest; second, or outermost, and seventh about equal. Top of the head and nape crimson-red. Forehead whitish, strongly tinged with light red, a shade of which is also seen on the cheek, still stronger on the middle of the belly. Under parts brownish-white, with a faint wash of yellowish on the belly. Back, rump, and wing-coverts banded black and white; upper tail-covert white, with occasional blotches. Tail-feathers black; first transversely banded with white; second less so; all the rest with whitish tips. Inner feathers banded with white on the inner web; the outer web with a stripe of white along the middle. Length, 9.75; wing, about 5.00. Female with the crown ashy; forehead pale red; nape bright red.

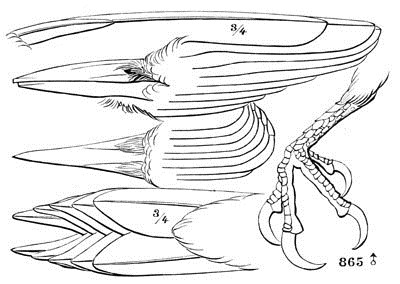

Centurus carolinus.

865 ♂

Hab. North America, from Atlantic coast to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Localities: Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 469, resident).

Specimens vary considerably in size (with latitude), and in the tinge of reddish on chin, breast, etc. The width of the dorsal bands differs in different specimens. The rump is banded; upper tail-coverts are generally immaculate, but are sometimes dashed with black. Specimens from the Mississippi Valley are generally more brightly colored than those from the Atlantic States, the lower parts more strongly tinged with red. Florida examples are smaller than northern ones, the black bars broader, the lower parts deeper ashy and strongly tinged with red, but of a more purplish shade than in western ones.

Centurus carolinus.

Habits. The Red-bellied Woodpecker is distributed throughout North America, from the Atlantic Coast to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. It is, however, much more abundant in the more southern and western portions. In the collections of the Smithsonian Institution none are recorded from farther north than Pennsylvania on the east and Nebraska Territory on the west, while others were obtained as far south as Florida. Nor am I aware that it is found, except very rarely, north of Pennsylvania on the Atlantic coast. I have never met with it in Eastern Massachusetts, although Mr. Audubon speaks of it as breeding from Maryland to Nova Scotia. Dr. Woodhouse found it common in the Indian Territory and in Texas. Wilson speaks of having found it abundant in Upper Canada, and in the northern parts of the State of New York. He also refers to its inhabiting the whole Atlantic States as far as Georgia and the southern extremity of Florida. Its absence in Eastern Massachusetts was noticed by Mr. Nuttall. It is not given by Thompson or Paine as one of the birds of Vermont, nor does Lieutenant Bland mention it as one of the birds of Nova Scotia, and it is not included by Sir John Richardson in the Fauna Boreali-Americana.

Mr. Audubon speaks of it as generally more confined to the interior of forests than the Hairy Woodpecker, especially during the breeding-season. He further states that he never met with its nest in Louisiana or South Carolina, but that it was not rare in Kentucky, and that, from the State of Maryland to Nova Scotia, it breeds in all convenient places, usually more in the woods than out of them. He also states that he has found the nests in orchards in Pennsylvania, generally not far from the junction of a branch with the trunk. He describes the hole as bored in the ordinary manner. The eggs are seldom more than four in number, and measure 1.06 inches in length and .75 of an inch in breadth. They are of an elliptical form, smooth, pure white, and translucent. They are not known to raise more than one brood in a season.

Wilson speaks of this species as more shy and less domestic than the Red-headed or any of the other spotted Woodpeckers, and also as more solitary. He adds that it prefers the largest high-timbered woods and the tallest decayed trees of the forest, seldom appearing near the ground, on the fences, or in orchards or open fields. In regard to their nesting, he says that the pair, in conjunction, dig out a circular cavity for the nest in the lower side of some lofty branch that makes a considerable angle with the horizon. Sometimes they excavate this in the solid wood, but more generally in a hollow limb, some fifteen inches above where it becomes solid. This is usually done early in April. The female lays five eggs, of a pure white, or almost semi-transparent. The young generally make their appearance towards the latter part of May. Wilson was of the opinion that they produced two broods in a season.

Mr. Dresser found this bird resident and abundant in Texas. It is also equally abundant in Louisiana and in Florida, and Mr. Ridgway considers it very common in Southern Illinois. Neither Mr. Boardman nor Mr. Verrill have found it in Maine. Mr. McIlwraith has, however, taken three specimens at Hamilton, Canada West, May 3, near Chatham. Mr. Allen gives it as a summer visitant in Western Massachusetts, having seen one on the 13th of May, 1863. It has also been taken several times in Connecticut, by Professor Emmons, who met with it, during the breeding-season, in the extreme western part of the State. Mr. Lawrence has found it near New York City, and Mr. Turnbull in Eastern Pennsylvania.

The eggs vary from an oblong to a somewhat rounded oval shape, are of a bright crystalline whiteness, and their measurements average 1.02 inches in length by .88 of an inch in breadth.

Centurus aurifrons, GrayYELLOW-BELLIED WOODPECKERPicus aurifrons, Wagler, Isis, 1829, 512.—Sundevall, Consp. Pic. 53. Centurus aurifrons, Gray, Genera.—Cabanis, Jour. 1862, 323.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 399. Centurus flaviventris, Swainson, Anim. in Menag. 1838 (2½ centenaries), 354.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 110, pl. xlii.—Heermann, P. R. Rep. X, c, 18.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 469 (resident in Texas).—Ib. Rep. Mex. Bound. II, 5, pl. iv. Centurus elegans, Lawrence, Ann. N. Y. Lyc. V, May, 1851, 116. Centurus santacruzi, Lawrence, Ann. N. Y. Lyc. V, 1851, 123 (not ofBonap.). Picus ornatus, Less. Rev. Zoöl. 1839, 102.

Sp. Char. Fourth and fifth quills nearly equal; third a little shorter; longer than the fourth. Back banded transversely with black and white; rump and upper tail-coverts pure white. Crown with a subquadrate spot of crimson, about half an inch wide and long; and separated from the gamboge-yellow at the base of the bill by dirty white, from the orbit and occiput by brownish-ash. Nape half-way round the neck orange-yellow. Under part generally, and sides of head, dirty white. Middle of belly gamboge-yellow. Tail-feathers all entirely black, except the outer, which has some obscure bars of white. Length about 9.50; wing, 5.00. Female without the red of the crown.

Hab. Rio Grande region of the United States, south into Mexico. Probably Arizona. Localities: Orizaba (Scl. P. Z. S. 1860, 252); Texas, south of San Antonio (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 469, resident).

Young birds are not different from adults, except in showing indication of dark shaft-lines beneath, becoming broader behind on the sides. The yellow of the nape extends over the whole side of the head.

Habits. This beautiful Woodpecker is abundant throughout the valley of the Rio Grande, from Eagle Pass to its mouth; how far to the west within our boundaries it occurs, I am not able to state. It is common throughout Mexico, and was found in the Guatemalan collection of Van Patten, though not mentioned by Sclater and Salvin. Dr. Woodhouse, in his Report on the zoölogy of Captain Sitgreaves’s expedition, speaks of finding it quite abundant in the neighborhood of San Antonio, Texas. He adds that west of the Rio San Pedro he did not meet with it. He speaks of it as having a loud, sharp cry, which it utters as it flies from tree to tree. He observed it mostly on the trunks of the mesquite (Algarobia), diligently searching in the usual manner of Woodpeckers. In the Report upon the birds of the Mexican Boundary Survey, it is mentioned by Mr. Clark as abundant on the Lower Rio Grande, as very shy, and as keeping chiefly about the mesquite. Lieutenant Couch speaks of it as very common throughout Tamaulipas.

Mr. Dresser found the Yellow-bellied Woodpecker plentiful from the Rio Grande to San Antonio, and as far north and east as the Guadaloupe, after which he lost sight of it. Wherever the mesquite-trees were large, there it was sure to be found, and very sparingly elsewhere. Near San Antonio it is quite common, but not so much so as the C. carolinus. At Eagle Pass, however, it was the more abundant of the two. He found it breeding near San Antonio, boring for its nest-hole into a mesquite-tree. Mr. Dresser was informed by Dr. Heermann, who has seen many of their nests, that he never found them in any other tree.

These birds were found breeding by Dr. Berlandier, and his collection. contained quite a number of their eggs. Nothing was found among his papers in relation to their habits or their manner of breeding. Their eggs, procured by him, are of an oblong-oval shape, and measure 1.05 inches in length by .85 of an inch in breadth.

Centurus uropygialis, BairdGILA WOODPECKERCenturus uropygialis, Baird, Pr. A. N. Sc. Ph. VII, June, 1854, 120 (Bill Williams River, N. M.)—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, III, pl. xxxvi.—Cab. Jour. 1862, 330.—Sundevall, Consp. 54.—Kennerly, P. R. R. X, b pl. xxxvi.—Heermann, X, c, 17. Coues, Pr. Avi. 1866, 54 (S. Arizona).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 399. Centurus hypopolius, (Bp.) Pucheran, Rev. et Mag. 1853, 163 (not Picus (Centurus) hypopolius, Wagler). Zebrapicus kaupii, Malherbe, 1855.—Gray, Catal. Br. Mex. Centurus sulfureiventer, Reichenbach, Handbuch, Picinæ, Oct. 1854, 410, figs. 4411, 4412.

Sp. Char. Third, fourth, and fifth quills longest, and about equal. Back, rump, and upper tail-coverts transversely barred with black and white, purest on the two latter. Head and neck all round pale dirty-brown, or brownish-ash, darkest above. A small subquadrate patch of red on the middle of the crown, separated from the bill by dirty white. Middle of the abdomen gamboge-yellow; under tail-coverts and anal region strongly barred with black. First and second outer tail-feathers banded black and white, as is also the inner web of the inner tail-feather; the outer web of the latter with a white stripe. Length, about 9.00; wing, 5.00. Female with the head uniform brownish-ash, without any red or yellow.

Hab. Lower Colorado River of the West, to Cape St. Lucas. South to Mazatlan. Localities: W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 54).

Habits. This species was first discovered by Dr. Kennerly in his route along the 35th parallel, and described by Professor Baird, in 1854. The Doctor encountered it almost continually during the entire march along the Big Sandy, Bill Williams Fork, and the Great Colorado; but it was so very shy that he had great difficulty in procuring specimens. Seated in the top of the tree, it was ever on guard; and, upon the approach of danger, flew away, accompanying its flight with the utterance of very peculiar notes. Its flight was in an undulating line, like that of other birds of this class.

Dr. Heermann found this Woodpecker abundant on the banks of the Gila River among the mesquite-trees. The giant cactus, often forty feet high, which grows abundantly on the arid hillsides throughout that whole section of country, was frequently found filled with holes bored out by this bird. The pith of the plant is extracted until a chamber of suitable size is obtained, when the juice exuding from the wounded surface hardens, and forms a smooth dry coating to the cavity, thus making a convenient place for the purposes of incubation. At Tucson, in Arizona, he found it frequenting the cornfields, where it might be seen alighting on the old hedge-posts in search of insects. Its note, he adds, resembles very much that of the Red-headed Woodpecker. He afterwards met with this bird in California, in considerable numbers, on the Colorado. Besides its ordinary notes, resembling those of the Melanerpes erythrocephalus, it varies them with a soft plaintive cry, as if hurt or wounded. He found their stomachs filled with the white gelatinous berry of a parasitic plant which grows abundantly on the mesquite-trees, and the fruit of which forms the principal food of many species of birds during the fall.

Dr. Coues gives this bird as rare and probably accidental in the immediate vicinity of Fort Whipple, but as a common bird in the valleys of the Gila and of the Lower Colorado, where it has the local name of Suwarrow, or Saguaro, on account of its partiality for the large cactuses, with the juice of which plant its plumage is often found stained.

Dr. Cooper found this Woodpecker abundant in winter at Fort Mohave, when they feed chiefly on the berries of the mistletoe, and are very shy. He rarely saw them pecking at the trees, but they seemed to depend for a living on insects, which were numerous on the foliage during the spring. They have a loud note of alarm, strikingly similar to that of the Phainopepla nitens, which associated with them in the mistletoe-boughs.

About the 25th of March he found them preparing their nests in burrows near the dead tops of trees, none of them, so far as he saw, being accessible. By the last of May they had entirely deserted the mistletoe, and were probably feeding their young on insects.

Genus MELANERPES, SwainsonMelanerpes, Swainson, F. B. A. II, 1831. (Type, Picus erythrocephalus.)

Melampicus (Section 3), Malherbe, Mém. Ac. Metz, 1849, 365.

Asyndesmus, Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 55. (Type, Picus torquatus.)

Gen. Char. Bill about equal to the head; broader than high at the base, but becoming compressed immediately anterior to the commencement of the gonys. Culmen and gonys with a moderately decided angular ridge; both decidedly curved from the very base. A rather prominent acute ridge commences at the base of the mandible, a little below the ridge of the culmen, and proceeds but a short distance anterior to the nostrils (about one third of the way), when it sinks down, and the bill is then smooth. The lateral outlines are gently concave from the basal two thirds; then gently convex to the tip, which does not exhibit any abrupt bevelling. Nostrils open, broadly oval; not concealed by the feathers, nor entirely basal. Fork of chin less than half lower jaw. The outer pair of toes equal. Wings long, broad; lengthened. Tail-feathers broad, with lengthened points.

The species all have the back black, without any spots or streaks anywhere.

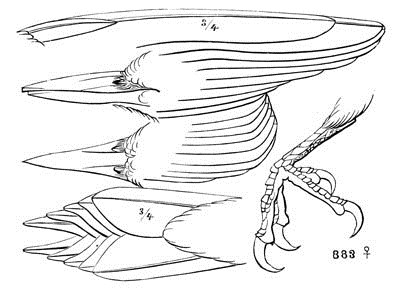

Melanerpes erythrocephalus.

883 ♀

Dr. Coues places M. torquatus in a new genus, Asyndesmus, characterized by a peculiar texture of the under part and nuchal collar, in which the fibres are disconnected on their terminal portion, enlarged and stiffened, almost bristle-like; otherwise the characters are much as in Melanerpes. It should, however, be noted, that the feathers of the red portion of the head in the other species have the same texture.

Species and VarietiesA. Sexes similar. Young very different from the adult.

M. torquatus. Feathers of the lower parts, as well as of frontal, lateral, and under portions of the head, with the fibres bristle-like. (Asyndesmus, Coues.) Upper parts wholly uniform, continuous, very metallic blackish-green. Adult. Forehead, lores, cheeks, and chin deep crimson, of a burnt-carmine tint; jugulum, breast, and a ring entirely around the nape, grayish-white; abdomen light carmine. Back glossed with purplish-bronze. Young without the red of the head, and lacking the grayish nuchal collar; abdomen only tinged with red, no purple or bronze tints above. Wing, 6.70; tail, 4.50. Hab. Western Province of the United States, from the Black Hills to the Pacific.

M. erythrocephalus. Feathers generally soft, blended; those of the whole head and neck with stiffened and bristle-like fibres in the adult. Secondaries, rump, and upper tail-coverts, with whole lower parts from the neck, continuous pure white. Two lateral tail-feathers tipped with white. Adult. Whole head and neck bright venous-crimson or blood-red, with a black convex posterior border across the jugulum; back, wings, and tail glossy blue-black. Young. Head and neck grayish, streaked with dusky; back and scapulars grayish, spotted with black; secondaries with two or three black bands; breast tinged with grayish, and with sparse dusky streaks. Wing, 5.90; tail, 3.90. Hab. Eastern Province of the United States, west to the Rocky Mountains.

B. Sexes dissimilar; young like the adult.

M. formicivorus. Forehead and a broad crescent across the middle of the throat (the two areas connected by a narrow strip across the lore), white, more or less tinged with sulphur-yellow. Rump, upper tail-coverts, abdomen, sides, and crissum, with patch on base of primaries, pure white, the sides and breast with black streaks. Other portions glossy blue-black.

♂. Whole crown and nape carmine. ♀ with the occiput and nape alone red.

More than the anterior half of the pectoral band immaculate♀ with the white frontal, black coronal, and red occipital bands of about equal width. Forehead and throat only slightly tinged with sulphur-yellow. Wing, 5.80; tail, 3.90; bill, 1.27. Hab. Pacific Province of United States, and Northern and Western Mexico … var. formicivorus.

♀ with the white frontal band only about half as wide as the black coronal, which is only about half as wide as the red occipital, band or patch. Forehead and throat bright sulphur-yellow. Wing, 5.40; tail, 3.65; bill, 1.23. Hab. Lower California … var. angustifrons.

Nearly the whole of the black pectoral band variegated with white streaksRelative width of the white, black, and red areas on the crown as in formicivorus. Wing, 5.50; tail, 3.75; bill, 1.22. Hab. Middle America, south of Orizaba and Mirador … var. striatipectus.131

♂. Nape, only, red (as in females of preceding races); ♀ without any red.

Whole breast streaked, the black and white being in about equal amount. Wing, 5.70; tail, 3.90; bill, 1.20. Hab. New Granada … var. flavigula.132

Melanerpes torquatus, BonapLEWIS’S WOODPECKERPicus torquatus, Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 31, pl. xx.—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 82.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 176, pl. ccccxvi.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 280, pl. cclxxii.—Sundevall, Consp. 51. Melanerpes torquatus, Bp. Consp. 1850, 115.—Heermann, J. A. N. Sc. Phil. 2d ser. II, 1853, 270.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. & Or. Route, 90, in P. R. R. Surv. VI, 1857.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 115.—Cooper & Suckley, 161.—Cassin. Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 327.—Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 1864, 112 (nesting).—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 406. Picus montanus, Ord. in Guthrie’s Geog. 2d Am. ed. II, 1815, 316. Picus lewisii, Drapiez. (Gray.) Asyndesmus torquatus, Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 55.

Sp. Char. Feathers on the under parts bristle-like. Fourth quill longest; then third and fifth. Above dark glossy-green. Breast, lower part of the neck, and a narrow collar all round, hoary grayish-white. Around the base of the bill and sides of the head to behind the eyes, dark crimson. Belly blood-red, streaked finely with hoary whitish. Wings and tail entirely uniform dark glossy-green. Female similar. Length about 10.50; wing, 6.50. Young without the nuchal collar, and the red of head replaced by black.

Hab. Western America from Black Hills to Pacific.

The peculiarities in the feathers of the under parts have already been adverted to. This structure appears to be essentially connected with the red feathers, since these have the same texture in the other species of the genus, wherever the color occurs. The remark may perhaps apply generally to the red feathers of most, if not all, Woodpeckers, and may be connected with some chemical or physical condition yet to be determined.

Habits. Lewis’s Woodpecker would seem to have a distribution throughout the Pacific Coast, from the sea-shore to the mountains, and from Puget Sound to the Gulf of California, and extending to the eastern border of the Great Plains, within the limits of the United States. They were first observed by Messrs. Lewis and Clarke, in their memorable journey to the Pacific. Subsequently Mr. Nuttall met with them in his westward journey, in the central chain of the Rocky Mountains. This was in the month of July. Among the cedar and pine woods of Bear River, on the edge of Upper California, he found them inhabiting the decayed trunks of the pine-trees, and already feeding their young. Afterwards, at the close of August, he met them in flocks on the plains, sixty miles up the Wahlamet. He describes them as very unlike Woodpeckers in their habits, perching in dense flocks, like Starlings, neither climbing branches nor tapping in the manner of their tribe, but darting after insects and devouring berries, like Thrushes. He saw them but seldom, either in the dense forests of the Columbia or in any settled part of California.

Townsend speaks of their arriving about the first of May on Bear River and the Columbia. Both sexes incubate, according to his observations.