полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

This Woodpecker has a single note or cry, sounding like chink, which it frequently repeats. When it flies, and often when it alights, this cry is more shrill and prolonged. They are very industrious, and are constantly employed in search of insects, chiefly in orchards and the more open groves. The orchard is its favorite resort, and it is particularly fond of boring the bark of apple-trees for insects. This fact, and the erroneous impression that it taps the trees for the sap, has given to these birds the common name of Sapsuckers, and has caused an unjust prejudice against them. So far from doing any injury to the trees, they are of great and unmixed benefit. Wilson, who was at great pains to investigate the matter, declares that he invariably found that those trees that were thus marked by the Woodpecker were uniformly the most thriving and the most productive. “Here, then,” adds Wilson, “is a whole species—I may say genus—of birds, which Providence seems to have formed for the protection of our fruit and forest trees from the ravages of vermin, which every day destroy millions of those noxious insects that would otherwise blast the hopes of the husbandman, and even promote the fertility of the tree, and in return are proscribed by those who ought to have been their protectors.”

The egg of this species is nearly spherical, pure white, and measures .83 by .72 of an inch.

Picus pubescens, var. gairdneri, AudGAIRDNER’S WOODPECKERPicus gairdneri, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 317.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 180.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 252 (not figured).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 91, pl. lxxxv, f. 2, 3.—Sundevall, Consp. 1866, 17.—Gray, Cat. 1868, 44.—Cooper & Suckley, 159.—Sclater, Catal. 1862, 334.—Malh. Monog. Picidæ, I, 123.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 201.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 377.—Lord, Pr. R. Art. Inst. IV, 1864, 111. Picus meridionalis, Nutt. Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 690 (not of Swainson).—Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. I, 1847, 55, 105. Picus turati, Malherbe, Mon. Pic. I, 125, tab. 29 (small race, 5.50, from Monterey, Cal., nearest pubescens). Dryobates turati, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 65. Dryobates homorus, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 65 (larger, more spotted style).

Sp. Char. Similar to pubescens in size and markings, but with less white on the wings. Varies from entire absence of exposed white spots on the middle and greater wing-coverts and innermost secondaries, with small spots on the quills, to spots on most of their feathers, but absent on some, and the spots generally larger.

Hab. Pacific coast of United States to Rocky Mountains. Darkest and with least white in Western Oregon and Washington.

In the preceding article we have given the comparative characters of this form, which we can only consider as a variety, and not very permanent or strongly marked at that.

As in pubescens, this race varies much in the color of the under parts, which are sometimes pure white, sometimes smoky-brown. It is suggested that this is partly due to a soiling derived from inhabiting charred trees. It is, at any rate, of no specific value.

Habits. Gairdner’s Woodpecker is the western representative and counterpart of the Downy Woodpecker of the east, resembling it in size and general habits, and only differing from it in certain exceptional characteristics already mentioned. It is found throughout western North America, probably from Mexico to the British Possessions, and from the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.

Dr. Cooper met with it in California, chiefly in the northern parts of the State, but did not observe any south of the Santa Clara Valley. Dr. Coues saw none in Arizona, or possibly a single specimen not positively ascertained.

Dr. Cooper found one of its nests near Santa Clara, on the 24th of May, containing young. It had been burrowed in a small and partly rotten tree, and was about five feet from the ground. From the fact that they were found breeding so far south he infers that among the mountains they probably occur much farther to the south, as do most other northern birds. He found them frequenting chiefly the smaller trees in the vicinity of the evergreen woods, where they were to be seen at all seasons industriously tapping the bark to obtain insects.

Dr. Newberry mentions finding them very common in Oregon, and also in Northern California. In Washington Territory, Dr. Suckley found them extremely common on the Lower Columbia, especially among the willow-trees lining its banks. They were resident throughout the winter, and in these situations were very abundant. In January, 1856, he found them so abundant among the willows growing on the islands in the delta of the Willamette, that he readily obtained eight specimens in the space of an hour. At that season they were very unwary, giving little heed to the presence of man, not even allowing the near discharge of a gun to interfere with their busy search for food.

Dr. Heermann speaks of it as neither common nor especially rare. He obtained several specimens among the mountains of Northern California.

Mr. Lord met with these Woodpeckers abundantly in the Northwestern Boundary Survey. They differed slightly in their habits from the P. harrisi, generally hunting for insects on the maples, alders, and stunted oaks, rather than on the pine-trees. Specimens were taken on Vancouver Island, Sumass Prairie, Colville, and the west slope of the Rocky Mountains at an altitude of seven thousand feet above the sea-level.

Mr. Ridgway found this Woodpecker to be unaccountably rare in the Sierra Nevada and all portions of the Great Basin, as well as in the Wahsatch and Uintah Mountains, even in places where the P. harrisi was at all times abundant. Indeed, he only met with it on two or three occasions, in the fall: first in the Upper Humboldt Valley, in September, where it was rare in the thickets along the streams; and again in the Wahsatch Mountains, where but a single brood of young was met with in August.

An egg of this species from Oregon, obtained by Mr. Ricksecker, is larger than that of the pubescens, but similar in shape, being very nearly spherical. It measures .96 of an inch in length by .85 in breadth.

Subgenus DYCTIOPICUS, BonapDyctiopicus, Bonap. Ateneo Ital. 1854, 8. (Type, Picus scalaris, Wagler.)

Dyctiopipo, Cabanis & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 74. (Same type.)

Char. Small species, banded above transversely with black or brown and white.

Of this group there are two sections,—one with the central tail-feathers entirely black, from Mexico and the United States (three species); the other with their feathers like the lateral black, banded or spotted with white (three species from southern South America). The northern section is characterized as follows:—

Common Characters. All the larger coverts and quills with white spots becoming transverse bands on innermost secondaries. Cheeks black with a supra-orbital and a malar stripe of white. Back banded alternately with black and white, but not on upper tail-coverts, nor four central tail-feathers. Beneath whitish, sides with elongated black spots; flanks and crissum transversely barred. Tail-feathers, except as mentioned, with spots or transverse bars of black. Head of male with red patch above (restricted in nuttalli), each feather with a white spot below the red. Female without red.

The characters of the species scalaris, with its varieties, and nuttalli, will be found under Picus.

Picus scalaris, WaglerLADDER-BACKED WOODPECKERPicus scalaris, Wagler, Isis, 1829, V, 511 (Mexico).—Bonap. Consp. 1850, 138.—Scl. P. Z. S. 1856, 307.—Sund. Consp. 18.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 94, pl. xli, f. 1.—Ib. Rep. Mex. Bound. II, 4, pl. iii.—Scl. Cat. 1862, 333.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 195.—Gray, Cat. 1868, 48.—Heerm. X, c, p. 18.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 379. Picus (Dyctiopicus) scalaris, Bon. Consp. Zygod. Aten. Ital. 1854, 8. Dyctiopipo scalaris, Cab. & Hein. Mus. 74. Picus gracilis, Less. Rev. Zoöl. 1839, 90 (Mexico). Picus parvus, Cabot, Boston Jour. N. H. V, 1845, 90 (Sisal, Yucatan). Picus orizabæ, Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 196 (Orizaba). Picus bogotus, Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 196; Jour. A. N. S. V, 1863, 460, pl. lii, f. 1 (Mex.). Picus bairdi (Scl. MSS.), Malherbe, Mon. Pic. I, 118, t. xxvii, f. 7, 8.—Scl. Cat. 333, (?) P. Z. S. 64, 177 (city of Mex.).—Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 76.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 196.—Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 52 (perhaps var. graysoni).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 468. Hab. Texas and New Mexico, to Arizona; south through Eastern Mexico to Yucatan. Picus scalaris, var. graysoni, Baird, MSS. Hab. Western Arizona; Western Mexico and Tres Marias.

Sp. Char. Back banded transversely with black and white from nape to rump (not upper tail-coverts). Quills and coverts with spots of white; forming bands on the secondaries. Two white stripes on sides of head. Top of head red, spotted with white. Nasal tufts brown. Beneath brownish-white, with black spots on sides, becoming bands behind. Outer tail-feathers more or less banded. Length, about 6.50; wing, 3.50 to 4.50; tail, about 2.50.

Hab. Guatemala, Mexico, and adjacent southern parts of United States. Localities: Xalapa (Scl. P. Z. S. 1859, 367); Cordova (Scl. 1856, 357); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 136); Orizaba (Scl. Cat. 333); S. E. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 468, breeds); W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 52); Yucatan (Lawr. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 205).

In the above diagnosis we have endeavored to express the average of characters belonging to a Woodpecker to which many names, based on trifling geographical variations, have been assigned, but which legitimately can be only considered as one species. This is among the smallest of the North American Woodpeckers, and in all its variations the wings are long, reaching as far as the short feathers of the tail. The upper parts generally are black, on the back, rump, and exposed feathers of the wings banded transversely with white, the black bands rather the narrower; the quills and larger coverts spotted with the same on both webs, becoming bands on the innermost secondaries. The upper tail-coverts and two inner tail-feathers on either side are black. The white bands of the back extend all the way up to the neck, without any interscapular interruption. The under parts are of a pale smoky brownish-white, almost with a lilac tinge; on the sides of the breast and belly are a few scattered small but elongated spots. The posterior parts of the sides under the wing and the under tail-coverts are obscurely banded transversely with black. The top of the head, extending from a narrow sooty frontlet at the base of the bill to a short, broad nuchal crest, is crimson in the male, each feather with a white spot between the crimson and the dark brown base of the feathers. The brown nasal tuft is scarcely different from the feathers of the forehead.

In a large series of specimens of this species, from a wide area of distribution, considerable differences are appreciable in size, but fewer in coloration than might be expected. Yucatan birds are the least (Picus parvus, Cabot; vagatus, Cassin), the wing measuring 3.30 inches. Those from Southern Mexico are but little larger (wing, 3.60). In Northern Mexico the wing is nearly 4 inches; in New Mexico it is 4.30. The markings vary but little. The black and white bands on the back are about of equal width, but sometimes one, sometimes the other, appears the larger; the more eastern have, perhaps, the most white. The pattern on the tail is quite constant. Thus, assuming the three outer feathers to be white, banded with black, the outermost may be said to have seven transverse bars of black, of which the terminal four (sometimes five) are distinct and perfect, the basal three (or two) confluent into one on the inner web (the extreme base of the feather white). The next feather has, perhaps, the same number of dark bands, but here only two (sometimes three) are continuous and complete; the innermost united together, the outer showing as scallops. The third feather has no continuous bands (or only one), all the inner portions being fused; the outer mere scallops, sometimes an oblique edging; generally, however, the interspaces of the dark bands are more or less distinctly traceable through their dusky suffusion, especially on the inner web of the outer feather. The number of free bands thus varies slightly, but the general pattern is the same. This condition prevails in nearly all the specimens before us from Yucatan and Mexico (in only one specimen from Arizona, and one or two from Texas), and is probably the typical scalaris of Wagler.

In specimens from the Rio Grande and across to Arizona the seven bands of the outer feather are frequently continuous and complete on both webs to the base, a slight suffusion only indicating the tendency to union in the inner web. The other feathers are much as described, except that the white interspaces of the black scallops penetrate deeper towards the shaft. This is perhaps the race to which the name of P. bairdi has been applied. We do not find, however, any decided reduction in the amount of red on the anterior portion of the head, as stated for this species (perhaps it is less continuous towards the front), except in immature birds; young females possibly losing the immature red of the crown, as with typical scalaris.

A third type of tail-marking is seen in specimens from the Pacific coast, and from the Tres Marias especially; also in some skins from Southwestern Arizona. Here the extreme forehead is black, with white spots; the red of the crown not so continuous anteriorly even as in the last-mentioned race. The general pattern of tail is as described, and the bars on the inner webs are also confluent towards the base, but we have only two or three transverse bars at the end of the outer feathers; the rest of outer web entirely white, this color also invading the inner. The second feather is similarly marked, sometimes with only one spot on outer web; the third has the black scallops restricted. This may be called var. graysoni, as most specimens in the Smithsonian collection were furnished by Colonel Grayson. The size is equal to the largest typical scalaris.

We next come to the Cape St. Lucas bird, described by Mr. Xantus as P. lucasanus. Here the bill and feet become disproportionally larger and more robust than in any described; the black bands of the back larger than the white, perhaps fewer in number. The continuous red of the head also appears restricted to a stripe above and behind the eye and on the occiput, although there are some scattered feathers as far forward as above the eyes. The specimens are, however, not in very good plumage, and this marking cannot be very well defined; the red may really be as continuous forward as in the last variety. The nasal tufts are brown, as in the typical scalaris. The outer three tail-feathers in most specimens show still more white, with one or two indistinct terminal bands only on the outer two; one or two additional spots, especially on inner web, and the sub-basal patch of inner web greatly reduced. Specimens vary here in this respect, as in other races of scalaris, but the average is as described.

Notwithstanding the decided difference between typical scalaris and lucasanus, the discovery of the variety graysoni makes it possible to consider both as extremes of one species. To nuttalli, however, it is but one step farther; a restriction of the red to the posterior half of the top of head, the white instead of brown nasal feathers, and the whiter under parts being the only positive characters. The markings of the tail are almost identical with those of lucasanus. The anterior portion of the back is, however, not banded, as in the several varieties described. For this reason it may therefore be questioned whether, if lucasanus and scalaris are one, nuttalli should not belong to the same series.

We thus find that the amount of black on the tail is greatest in Southern and Southeastern Mexican specimens, and farther north it begins to diminish; in Western Mexico it is still more reduced, while at Cape St. Lucas the white is as great in amount as in the Upper Californian P. nuttalli.

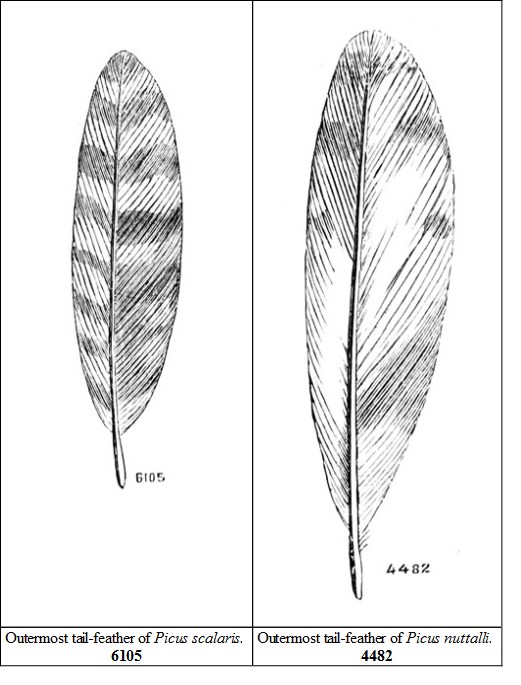

The characters given above for the different varieties or races of Picus scalaris, as far as they relate to the tail, may be expressed in the following table, illustrated by the accompanying diagram, showing the markings of outer tail-feather in scalaris and nuttalli.

Outer tail-feathers with seven distinct transverse black bands.

These bands confluent on inner web near the base … var. scalaris.

Bands distinct on inner web … var. bairdi.

Bands on outer tail-feather distinct on outer webs at end only, obsolete or wanting towards base (as in nuttalli).

Tarsus, .68. Bill and legs as in average … var. graysoni.

Tarsus, .78. Bill and legs very stout … var. lucasanus.

Habits. This species belongs to our southern and southwestern fauna, entering our borders from Mexico, occurring from the valley of the Rio Grande to Southeastern California, and the slopes of the Rocky Mountains south of the 35th parallel. It is found throughout Mexico to Yucatan and Guatemala.

Dr. Samuel Cabot obtained a single specimen of this bird at Yucatan, which he described under the name of P. parvus, in the Boston Journal of Natural History, V, p. 92. It was procured early in December, 1841, in the neighborhood of Ticul, Yucatan. Dr. Kennerly considered it a not uncommon species in the vicinity of Boca Grande; especially wherever there were large trees. The same naturalist, in his Report on the birds of Lieutenant Whipple’s expedition, states that he very often saw this bird near San Antonio, Texas, as well as during the march several hundred miles west of that place, but that, after leaving the Rio Grande, he did not meet with it until he reached the head-waters of Bill Williams Fork. From thence to the Great Colorado River he saw it frequently, wherever there was any timber; but it was very shy, alighting on the tops of the leafless cotton-wood trees, and keeping a vigilant lookout.

Dr. Heermann, in his Report on the birds of Lieutenant J. G. Parke’s expedition, states that he observed this Woodpecker in the southernmost portion of California, and found it more and more abundant as he advanced towards Texas, where it was quite common. The same naturalist, in his Report on the birds of Lieutenant Williamson’s expedition, remarks that he procured this bird first at Vallicita, but found it abounding in the woods about Fort Yuma. He considered the species as new to the California fauna, though frequently seen in Texas, several of the expeditions having collected it.

Dr. Woodhouse, in his Report on the birds of Sitgreaves’s expedition to the Zuñi and the Colorado speaks of finding this beautiful little Woodpecker abundant in Texas, east of the Pecos River. During his stay in San Antonio and its vicinity, he became quite familiar with it. It was to be seen, at all times, flying from tree to tree, and lighting on the trunk of the mesquites (Algarobia), closely searching for its insect-food. In its habits and notes, he states, it much resembles the common Hairy Woodpecker. Dr. Woodhouse elsewhere remarks that he did not meet with this bird west of the Rio San Pedro, in Texas. In regard to its breeding-habits, so far as I am aware, they are inferred rather than known. It is quite probable they are not unlike those of the Picus pubescens, which it so closely resembles. The eggs in the collection of the Smithsonian were obtained with the collections of the late Dr. Berlandier of Matamoras, in the province of Tamaulipas, Mexico.

Dr. Cooper states that this Woodpecker is abundant in the Colorado Valley, and that they are sometimes seen on the bushes covering the neighboring mountains. In habits he regards them the exact counterpart of P. nuttalli, to which they are allied.

Mr. Dresser found them resident and very common throughout all Texas and Northeastern Mexico. It breeds abundantly about San Antonio, boring into any tree it finds most suitable for its purposes.

Dr. Coues regards Fort Whipple as about the northern limit of this species in Arizona. It is not very common, is only a summer resident, and breeds sparingly there. Farther south, throughout the Territory, and in the Colorado Valley, he found it abundant. It does not cross the Colorado Desert into California, and is there replaced by P. nuttalli. It extends south into Central America. A bird shot by Dr. Coues, June 5, appeared to be incubating; young birds were taken just fledged July 10. The nest was in the top of a live-oak tree. Malherbe, who speaks of this Woodpecker as exclusively Mexican, states that he has been informed that it is abundant in that country, where it may be seen at all times, climbing over the trunks and branches of trees. It is said to be very familiar and unwary, living commonly in gardens and orchards through the greater part of the year, and many of them nesting there, though in regard to their manner of nesting he has no information.

The egg of this Woodpecker in shape is most similar to the P. villosus, being of an oblong-oval. It is larger than the pubescens, and not of so clear a white color. It measures exactly one inch in length by .75 of an inch in breadth.

Picus scalaris, var. lucasanus, XantusTHE CAPE WOODPECKERPicus lucasanus, Xantus, Pr. A. N. S. 1859, 298, 302.—Malherbe, Mon. Picidæ, I, 166.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 195.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 381.

Sp. Char. General appearance that of Picus nuttalli and scalaris. Bill stout, as long as or longer than the head. Above black, banded transversely with white on the back and scapulars to the nape, the white narrower band, the rump and inner tail-feathers entirely black; quills with a row of white spots on each web; the outer square, the inner rounded, these spots on the tertials becoming transversely quadrangular. Beneath brownish-white, with rounded black spots on the sides of the breast, passing behind on the flanks and under tail-coverts into transverse bars. Greater inner wing-coverts transversely barred. Outer two tail-feathers white, with one, sometimes two terminal bars, next to which are one or two bars on the inner web only; third feather black, the outer web mostly white, with traces of a terminal black bar; sometimes there is a greater predominance of black on the inner web. Two white stripes on side of head, one starting above, the other below the eye, with a tendency to meet behind and form a whitish collar on the nape. Male with the entire top of the head streaked with red, becoming more conspicuous behind; each red streak with a white spot at base. Feathers covering the nostrils smoky-brown. Length, 7.15; extent, 12.15; wing, 4.00; bill above, 1.00; middle toe and claw, .80; tarsus, .76.

Hab. Cape St. Lucas.

Of the distinctness of this bird as a species from P. nuttalli and scalaris I had at one time no doubt; but the discovery that the otherwise typical scalaris from Mazatlan and Western Mexico generally have the same markings on the tail has induced me to consider it as a kind of connecting link. I have, however, thought it best to give a detailed description for comparison. Of about the same size with nuttalli, the bill and feet are much larger. The legs, indeed, are nearly, if not quite, as large as those of male P. villosus from Pennsylvania; the bill, however, is somewhat less. The relations to P. scalaris are seen in the dorsal bands extending to the nape, the smoky-brown feathers of the nostrils, the red on the whole top of head (scattering anteriorly), the brownish shade beneath, the width of the white cheek-bands, etc. On the other hand, it has the black bands of the back rather wider than the white, as in nuttalli, and the white outer tail-feathers even less banded with black. The two outer are entirely white, with one terminal black bar; one or two spots on the outer web; and two or three bands on the inner, with a sub-basal patch on the inner web, even smaller than in nuttalli. It is rarely that even two continuous transverse bands can be seen to cross both webs of the tail. The bill and feet are much larger.