полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

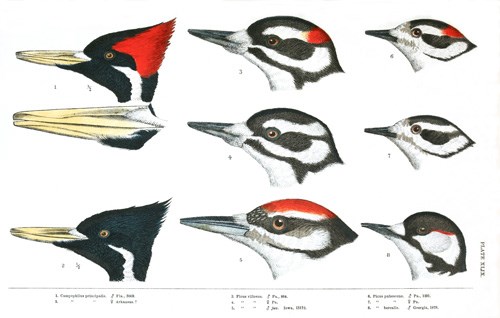

2. C. imperialis. No white stripe on the sides of the neck. More white on the wings. Bristly feathers at the base of the bill black. Hab. South Mexico; Guatemala.

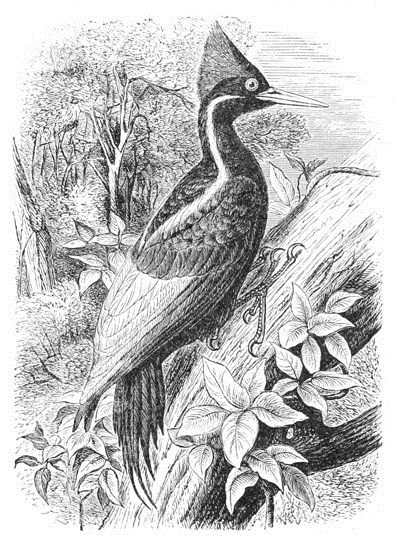

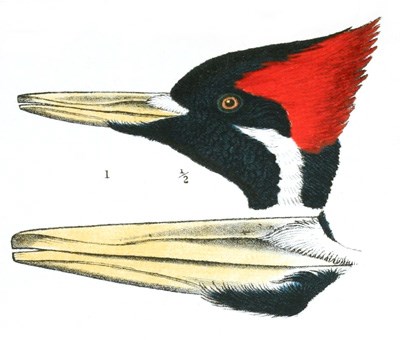

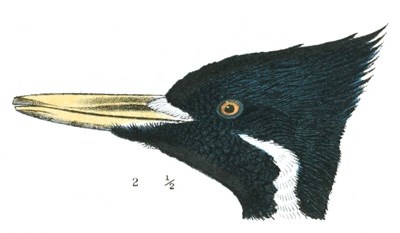

Campephilus principalis, GrayIVORY-BILLED WOODPECKERPicus principalis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 173.—Wilson, Am. Orn. IV, 1811, 20, pl. xxxix, f. 6.—Wagler, Syst. Avium, 1827, No. 1.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 341; V, 525, pl. lxvi.—Ib. Birds America, IV, 1842, 214, pl. cclvi.—Sundevall, Consp. Pic. 4. Dendrocopus principalis, Bon. List, 1838. Campephilus principalis, Gray, List Genera, 1840.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 83.—Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, II, 100.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 468 (breeds in Brazos and Trinity, Texas).—Gray, Cat. 53.—Allen, Birds E. Florida, 301. Dryotomus (Megapicus) principalis, Bon. Con. Zyg. Aten. Ital. 1854, 7. Dryocopus principalis, Bon. Consp. 1850, 132. White-billed Woodpecker, Catesby, Car. I, 16.—Pennant, Latham.

Sp. Char. Fourth and fifth quills equal; third a little shorter. Bill horn-white. Body entirely of a glossy blue-black (glossed with green below); a white stripe beginning half an inch posterior to the commissure, and passing down the sides of the neck, and extending down each side of the back. Under wing-coverts, and the entire exposed portion of the secondary quills, with ends of the inner primaries, bristles, and a short stripe at the base of the bill, white. Crest scarlet, upper surface black. Length, 21.00; wing, 10.00. Female similar, without any red on the head, and with two spots of white on the end of the outer tail-feather.

Hab. Southern Atlantic and Gulf States. North to North Carolina and mouth of the Ohio; west to Arkansas and Eastern Texas. Localities: Brazos and Trinity Rivers, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 468, breeds).

In the male the entire crown (with its elongated feathers) is black. The scarlet commences just above the middle of the eye, and, passing backwards a short distance, widens behind and bends down as far as the level of the under edge of the lower jaw. The feathers which spring from the back of the head are much elongated above; considerably longer than those of the crown. In the specimen before us the black feathers of the crest do not reach as far back as the scarlet.

Reference has already been made to the Cuban variety of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker named C. bairdi by Mr. Cassin, and differing in smaller size; extension of the white cheek-stripe to the very base of the bill, and the excess in length of the upper black feathers of the crest over the scarlet. These features appear to be constant, and characteristic of a local race.

For the reasons already adduced, we drop C. imperialis from the list of North American birds, although given as such by Audubon.

Campephilus principalis.

Habits. So far as we have information in regard to the geographical distribution of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, it is chiefly restricted in its range to the extreme Southern States, and especially to those bordering on the Gulf of Mexico. Wilson states that very few, if any, are ever found north of Virginia, and not many even in that State. His first specimen was obtained near Wilmington, N. C. It is not migratory, but is a resident where found.

Mr. Audubon, who is more full than any other writer in his account of this bird, assigns to it a more extended distribution. He states that in descending the Ohio River he met with it near the confluence of that river with the Mississippi, and adds that it is frequently met with in following the windings of the latter river either downwards towards the sea, or upwards in the direction of the Missouri. On the Atlantic he was inclined to make North Carolina the limit of its northern distribution, though now and then individuals of the species have been accidentally met with as far north as Maryland. To the westward of the Mississippi he states that it is found in all the dense forests bordering the streams which empty into it, from the very declivities of the Rocky Mountains. The lower parts of the Carolinas, Georgia, North Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, are, however, its favorite resorts, and in those States it constantly resides.

It was observed by Dr. Woodhouse in the timber on the Arkansas River, and in Eastern Texas, but quite rarely in both places. It was not, however, met with in any other of the government expeditions, either to the Pacific, in the survey of the railroad routes, or in that for the survey of the Mexican boundary line. It is given as a bird of Cuba by De la Sagra, in his catalogue of the birds of that island, as observed by him, October, 1850, and by Dr. John Gundlach, in his list of the birds that breed in Cuba. It is not mentioned by Gosse among the birds of Jamaica, nor by the Newtons as found in St. Croix. As it is not a migratory bird, it may be regarded as breeding in all its localities, except where it is obviously an accidental visitant.

Wilson, who never met with the nest of this Woodpecker, states, on the authority of reliable informants, that it breeds in the large-timbered cypress swamps of the Carolinas. In the trunks of these trees at a considerable height from the ground, both parents working alternately, these birds dig out a large and capacious cavity for their eggs and young. Trees thus dug out have frequently been cut down with both the eggs and the young in them. The hole was described to Wilson as generally a little winding, to keep out the rain, and sometimes five feet deep. The eggs were said to be generally four, sometimes five in number, as large as pullets’, pure white, and equally thick at both ends. The young make their appearance about the middle or end of June.

Mr. Audubon, whose account of the breeding-habits of the Ivory-bill is given from his own immediate observations, supplies a more minute and detailed history of its nesting. He states that it breeds earlier in spring than any other species of its tribe, and that he has observed it boring a hole for that purpose as early as the beginning of March. This hole he believed to be always made in the trunk of a live tree, generally an ash or a hackberry, and at a great height. It pays great regard to the particular situation of the tree and the inclination of the trunk, both with a view to retirement and to secure the aperture against rains. To prevent the latter injury, the hole is generally dug immediately under the protection of a large branch. It is first bored horizontally a few inches, then directly downward, and not in a spiral direction, as Wilson was informed. This cavity is sometimes not more than ten inches in depth, while at other times it reaches nearly three feet downward into the heart of the tree. The older the bird, the deeper its hole, in the opinion of Mr. Audubon. The average diameter of the different nests which Mr. Audubon examined was about seven inches in the inner parts, although the entrance is only just large enough to admit the bird. Both birds work most assiduously in making these excavations. Mr. Audubon states that in two instances where the Woodpeckers saw him watching them at their labors, while they were digging their nests, they abandoned them. For the first brood, he states, there are generally six eggs. These are deposited on a few chips at the bottom of the hole, and are of a pure white color. The young may be seen creeping out of their holes about a fortnight before they venture to fly to any other tree. The second brood makes its appearance about the 15th of August. In Kentucky and Indiana the Ivory-bill seldom raises more than one brood in a season. Its flight is described by Audubon as graceful in the extreme, though seldom prolonged to more than a few hundred yards at a time, except when it has occasion to cross a large river. It then flies in deep undulations, opening its wings at first to their full extent, and nearly closing them to renew their impulse. The transit from tree to tree is performed by a single sweep, as if the bird had been swung in a curved line from the one to the other.

Except during the love-season it never utters a sound when on the wing. On alighting, or when, in ascending a tree, it leaps against the upper parts of the trunk, its remarkable voice may be constantly heard in a clear, loud, and rather plaintive tone, sometimes to the distance of half a mile, and resembling the false high note of a clarionet. This may be represented by the monosyllable pait thrice repeated.

The food of this Woodpecker consists principally of beetles, larvæ, and large grubs. They are also especially fond of ripe wild grapes, which they eat with great avidity, hanging by their claws to the vines, often in the position of a Titmouse. They also eat ripe persimmons, hackberries, and other fruit, but are not known to disturb standing corn nor the fruits of the orchard.

These birds attack decaying trees so energetically as often to cause them to fall. So great is their strength, that Audubon has known one of them to detach, at a single blow, a strip of bark eight inches long, and, by beginning at the top branch of a dead tree, tear off the bark to the extent of thirty feet in the course of a few hours, all the while sounding its loud notes.

Mr. Audubon further states that this species generally moves in pairs, that the female is the least shy and the most clamorous, and that, except when digging a hole for the reception of their eggs, they are not known to excavate living trees, but only those attacked by worms. When wounded, they seek the nearest tree, and ascend with great rapidity by successive hops. When taken by the hand, they strike with great violence, and inflict severe wounds with their bills and claws.

Mr. Dresser states that these birds were found on the Brazos River, and also on the Trinity, where they were by no means rare.

Wilson dwells at some length and with great force upon the great value of these birds to our forests. They never injure sound trees, only those diseased and infested with insects. The pine timber of the Southern States is often destroyed, thousands of acres in a season, by the larvæ of certain insects. In Wilson’s day this was noticeable in the vicinity of Georgetown, S. C., and was attributed by him to the blind destruction of this and other insect-eating birds.

An egg of this species (Smith. Coll., No. 16,196) taken near Wilmington, N. C., by Mr. N. Giles, measures 1.35 inches in length by .95 of an inch in breadth. It is of a highly polished porcelain whiteness, and is much more oblong in shape and more pointed than are the eggs of Hylotomus pileatus.

Genus PICUS, LinnæusPicus, Linn. Syst. Nat. 1748. (Type, Picus martius, L.)

Picus villosus.

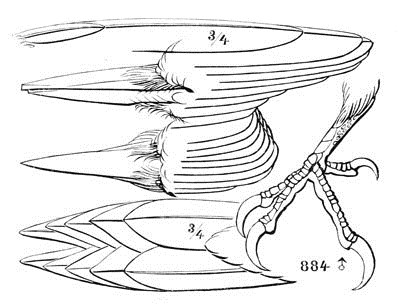

884 ♂

Gen. Char. Bill equal to the head, or a little longer; the lateral ridges conspicuous, starting about the middle of the base of the bill; the basal elongated oval nostrils nearest the commissure; the ridges of the culmen and gonys acute, and very nearly straight, or slightly convex towards the tip; the bill but little broader than high at the base, becoming compressed considerably before the middle. Feet much as in Campephilus; the outer posterior toe longest; the outer anterior about intermediate between it and the inner anterior; the inner posterior reaching to the base of the claw of the inner anterior. Tarsus about equal to the inner anterior toe; shorter than the two other long toes. Wings rather long, reaching to the middle of the tail, rather rounded; the fourth and fifth quills longest; the quills rather broad and rounded.

In the genus Picus, as characterized above, are contained several subdivisions more or less entitled to distinct rank, and corresponding with peculiar patterns of coloration. Thus, taking the P. villosus as the type, P. borealis has proportionally much longer primaries; the spurious primary smaller; the bill is considerably more attenuated, and even concave in its lateral outlines. The wings are still longer in P. albolarvatus. The species may be arranged as follows:—

A. Black above, and white beneath. Wings spotted with white; a black maxillary stripe.

a. Two white stripes on the side of the head, one above, and the other below, the ear-coverts, which are mostly black. First quill shorter than sixth. Tail-feathers broad and obtuse at ends, the narrowed tips of middle feathers very short.

DRYOBATES, Boie. Middle of back streaked longitudinally and continuously with white. Maxillary and auricular black stripes not confluent; the latter running into the black of the nape. Beneath white without spots. Red of head confined to a narrow nuchal band.

1. P. villosus. Outer tail-feathers immaculate white, great variation in size with latitude. Length, 7.00 to 10.00.

All the quills, with middle and greater wing-coverts, with large white spots. Hab. Eastern North America … var. villosus.

Innermost quills and some of the coverts entirely black, or unspotted with white. Remaining spots reduced in size. (Var. jardini similar, but much smaller, 7.00, and lower parts smoky-brown.) Hab. Middle and western North America, and south to Costa Rica … var. harrisi.

2. P. pubescens. Outer tail-feather white, with transverse black bands; length about 6.25.

All the quills, with middle and greater wing-coverts, with large white spots. Hab. Eastern North America … var. pubescens.

Innermost quills and some of the coverts entirely black; remaining white spots reduced in size. Hab. Western North America … var. gairdneri.

DYCTIOPICUS, Bon. Whole back banded transversely with black and white. Beneath white, with black spots on sides. Maxillary and auricular black stripes confluent at their posterior ends, the latter not running into the nape. In the males at least half of top of head red. Length, about 6.50.

3. P. scalaris. Anterior portion of the back banded with white; lores and nasal tufts smoky brown. Black stripes on sides of the head very much narrower than the white ones, and not connected with the black of the shoulders. Male with the whole crown red.

Outer web of lateral tail-feathers barred with black to the base. White bands on back exceeding the black ones in width; red of the crown very continuous, on the forehead predominating over the black and white. (Sometimes the black at base of inner web of lateral tail-feather divided by white bars.) Hab. Southern and Eastern Mexico, and Rio Grande region of United States … var. scalaris.

Outer web of lateral tail-feather barred with black only toward end. Red of crown much broken anteriorly, and in less amount than the black and white mixed with it. White bands of the back not wider, generally much narrower than the black ones.

Bill, .90; tarsus, .70. Red of crown extending almost to the bill. Hab. Western Mexico, up to Western Arizona … var. graysoni.

Bill, 1.10; tarsus, .75. Red of crown disappearing about on a line above the eye. Hab. Cape St. Lucas … var. lucasanus.

4. P. nuttalli. Anterior portion of back not banded with white; lores and nasal tufts white. Black stripes on side of the head very much broader than the white ones, and connected by a narrow strip with the black of the shoulders. Male with only the nape and occiput red. Hab. California (only).

b. One white stripe, only, on side of head, and this occupying whole auricular region. Tail-feathers narrowed at ends, the points of the middle ones much elongated. First quill longer than sixth. Bill very small, much shorter than head.

PHRENOPICUS, Bonap. Back and wings transversely banded with black and white, and sides spotted with black, as in Dyctiopicus.

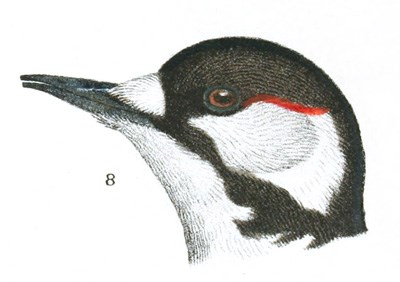

5. P. borealis. Red of male restricted to a concealed narrow line on each side of the occiput, at the junction of the white and black. Maxillary black stripe very broad and conspicuous, running back to the series of black spots on sides of breast. Three outer tail-feathers more or less white, with a few bars of black near their ends, principally on inner webs. Hab. South Atlantic States.

B. Body entirely continuous black; head all round immaculate white. First quill shorter than sixth.

XENOPICUS, Baird. Tail and primaries as in “A,” but much more lengthened. Bill as in Dryobates, but more slender.

6. P. albolarvatus. Red of male a narrow transverse occipital crescent, between the white and the black. Basal half, or more, of primaries variegated with white, this continuous nearly to the end of outer webs; inner webs of secondaries with large white spots toward their base. Hab. Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges, Pacific Province, United States.

Subgenus DRYOBATES, BoieDryobates, Boie, 1826. (Type, Picus pubescens, fide Cabanis, Mus. Hein.)

Trichopicus, Bonap. 1854.

Trichopipo, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. 1863, 62.

According to Cabanis, as above cited, Dryobates, as established by Boie in 1826, had the Picus pubescens as type, although extended in 1828 to cover a much wider ground. As a subgeneric name, therefore, it must take preference of Trichopicus of Bonaparte, which, like all the allied names of this author, Cabanis rejects at any rate as hybrid and inadmissible.

The synopsis under the head of Picus will serve to distinguish the species in brief.

Picus harrisi.

The small black and white Woodpeckers of North America exhibit great variations in size and markings, and it is extremely difficult to say what is a distinct species and what a mere geographical race. In none of our birds is the difference in size between specimens from a high and a low latitude so great, and numerous nominal species have been established on this ground alone. There is also much variation with locality in the amount of white spotting on the wings, as well as the comparative width of the white and black bars in the banded species. The under parts, too, vary from pure white to smoky-brown. To these variations in what may be considered as good species is to be added the further perplexities caused by hybridism, which seems to prevail to an unusual extent among some Woodpeckers, where the area of distribution of one species is overlapped by a close ally. This, which can be most satisfactorily demonstrated in the Colaptes, is also probably the case in the black and white species, and renders the final settlement of the questions involved very difficult.

After a careful consideration of the subject, we are not inclined to admit any species or permanent varieties of the group of four-toed small white and black Woodpeckers as North or Middle American, other than those mentioned in the preceding synopsis.

PLATE XLIX.

1. Campephilus principalis. ♂ Fla., 3869.

2. Campephilus principalis. ♀ Arkansas.?

3. Picus villosus. ♂ Pa., 884.

4. Picus villosus. ♀ Pa.

5. Picus villosus. ♂ juv. Iowa, 13172.

6. Picus pubescens. ♂ Pa., 1291.

7. Picus pubescens. ♀ Pa.

8. Picus borealis. ♂ Georgia, 1878.

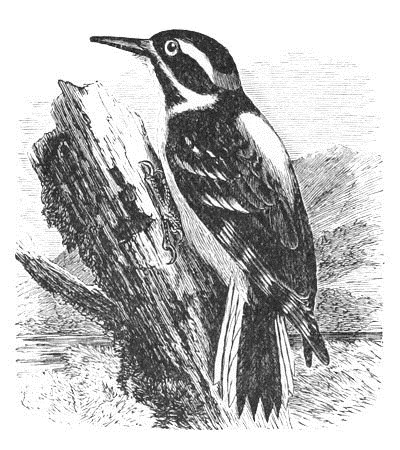

Picus villosus, LinnæusHAIRY WOODPECKER; LARGER SAPSUCKERVar. canadensis.—Northern and Western regions

? Picus leucomelas, Boddært, Tabl. Pl. Enl. 1783 (No. 345, f. 1, Gray).—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 199. Dryobates leucomelas, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 67. ? Picus canadensis, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 437.—? Latham, Ind. Orn. I, 1790, 231.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 188, pl. ccccxvii.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 177.—Ib. Birds America, IV, 1842, 235, pl. cclviii.—Bonap. Consp. 1850, 137.—Ib. Aten. Ital. 1854, 8. Picus villosus, Forster, Philos. Trans. LXII, 1772, 383.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 84.—Cassin, P. A. N. S. 1863, 199.—Gray, Catal. 1868, 45.—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chicago Ac. Sc. I, 1869, 274 (Alaska).—Finsch, Abh. Nat. III, 1872, 60 (Alaska).—Samuels, 87. Picus (Dendrocopus) villosus, Sw. F.-Bor. Am. II, 1831, 305. Picus phillipsi, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 186, pl. ccccxvii.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 177.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 238, pl. cclix (immature, with yellow crown).—Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 686.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 199. Picus martinæ, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 181, pl. ccccxvii.—Ib. Syn. 1839, 178.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 240, pl. cclx (young male, with red feathers on crown).—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 199. Picus rubricapillus, Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 685 (same as preceding). Picus septentrionalis, Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 684.

Var. villosus.—Middle StatesPicus villosus, Linnæus, Syst. Nat. I, 1758, 175.—Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 64, pl. cxx.—Wilson, Am. Orn. I, 1808, 150, pl. ix.—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 22.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 164, pl. ccccxvi.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 244, pl. cclxii.—Bonap. Conspectus, 1850, 137.—Sundevall, Mon. Pic. 17.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 84. Picus leucomelanus, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 18 (young male in summer). Hairy Woodpecker, Pennant, Latham. Dryobates villosus, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 66.

Var. auduboni.—Southern StatesPicus auduboni, Swainson, F. B. A. 1831, 306.—Trudeau, J. A. N. Sc. Ph. VII, 1837, 404 (very young male, with crown spotted with yellow).—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 194, pl. ccccxvii.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, 259, pl. cclxv.—Nutt. Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 684.—Cass. P. A. N. S. 1863, 199. Picus villosus, Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1859 (Bahamas, winter).—Allen, B. E. Fla. 302.

Sp. Char. Above black, with a white band down the middle of the back. All the middle and larger wing-coverts and all the quills with conspicuous spots of white. Two white stripes on each side of the head; the upper scarcely confluent behind, the lower not at all so; two black stripes confluent with the black of the nape. Beneath white. Three outer tail-feathers with the exposed portions white. Length, 8.00 to 11.00; wing, 4.00 to 5.00; bill, 1.00 to 1.25. Male, with a nuchal scarlet crescent (wanting in the female) covering the white, generally continuous, but often interrupted in the middle. Immature bird of either sex with more or less of the whole crown spotted with red or yellow, or both, sometimes the red almost continuous.

Hab. North America, to the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains, and (var. canadensis) along the 49th parallel to British Columbia; Sitka; accidental in England.

In the infinite variation shown by a large number of specimens in the markings of the wings, so relied on by authors to distinguish the species of the black and white spotted North American Woodpeckers having a longitudinal band of white down the back, it will be perhaps our best plan to cut them rigorously down to two, the old-fashioned and time-honored P. villosus and pubescens; since the larger and more perfect the series, the more difficult it is to draw the line between them and their more western representatives. The size varies very greatly, and no two are alike in regard to the extent and number of the white spots. Beginning at one end of the chain, we find the white to predominate in the more eastern specimens. Thus in one (20,601) from Canada, and generally from the north, every wing-covert (except the smallest) and every quill shows externally conspicuous spots or bands of white; the middle coverts a terminal band and central spot; the greater coverts two bands on the outer web, and one more basal on the inner; and every quill is marked with a succession of spots in pairs throughout its length,—the outer web as bands reaching nearly to the shaft; the inner as more circular, larger spots. The alula alone is unspotted. This is the typical marking of the P. leucomelas or canadensis of authors. The white markings are all larger respectively than in other forms.