полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

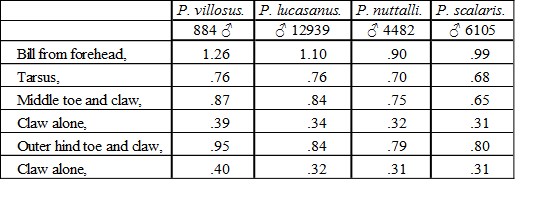

The following measurements taken from the largest specimens before us of Dyctiopicus, and one of P. villosus, will illustrate what has been said of the size of bill and feet of P. lucasanus.

Habits. Nothing distinctive is known of the habits of this race.

Picus nuttalli, GambelNUTTALL’S WOODPECKERPicus nuttalli, Gambel, Pr. A. N. Sc. I, April, 1843, 259 (Los Angeles, Cal.).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 93.—Sundevall, Consp. Pic. 19.—Malh. Mon. Pic. I, 100.—Cassin, P. A. N. S. 1863, 195.—Gray, Cat. 1868, 50.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 378. Picus scalaris, (Wagler) Gambel, J. A. N. Sc. Ph. 2d ser. I, Dec. 1847, 55, pl. ix, f. 2, 3 (not of Wagler). Picus wilsoni, Malherbe, Rev. Zoöl. 1849, 529.—Bonap. Consp. 1850, 138. Picus (Trichopicus) wilsoni, Bonap. Consp. Zyg. Aten. Ital. 1854, 8.

Sp. Char. Back black, banded transversely with white, but not on upper tail-coverts, nor as far forward as the neck. Greater and middle coverts and quills with spots or bands of white. Crown black, with white spots, sometimes wanting. On the nape a patch of white, behind this unbanded black. Occiput and nape crimson in the male. Tufts of feathers at the base of the bill white. Sides of the head black, with two white stripes, one above the eye and passing down on the side of the neck, the other below and cut off behind by black. Under parts smoky yellowish-white, spotted on the sides of the breast, and banded on flank and crissum with black. Predominant character of the outer tail-feather white, with two or three interrupted bands towards end; none at base. Length, about 7.00; wing, 4.50. Female with the top of the head uniform black, or sometimes spotted with white.

Hab. Coast region of California.

Third, fourth, and fifth quills nearly equal and longest; second intermediate between the seventh and eighth. General color above black, barred transversely with white on the back, rump, and flanks; the upper surface of tail and tail-coverts, and a broad patch on the upper part of the back about half an inch long, pure black. The white bands measure about .12 of an inch, the black about twice as much. The top of the head is black, each feather with a short streak of white; on the extreme occiput and the nape is a transverse patch of crimson, each feather having a white spot just below the crimson. The crimson patch is usually as far from the base of the bill above as this is from its point. The sides of the head may be described as black; a white stripe commences on the upper edge of the eye, and, passing backwards, margins the crimson, and extends on down the side of the neck to a patch of white, apparently connected with its fellow on the opposite side by white spots. Another narrow white stripe commences at the nostrils, (the bristles of which are whitish,) and passes as far as the occiput, where it ceases in the middle of the black of the cheeks. There are thus two white streaks on the side of the head bordering a black one passing through the eye. The under parts generally are white, with a dirty yellow tinge. The sides of the breast and body are faintly streaked with black; the flanks barred with the same. The under coverts are barred with black.

The three outer tail-feathers are yellowish-white, with two or three interrupted bars of black on the posterior or terminal fourth, and a concealed patch of black on the inner web near the end. Only the terminal band is continuous across, sometimes the others; always interrupted along the shaft, and even reduced to rounded spots of black on one or both webs. No distinct bands are visible on raising the crissum. The black patch on inner web of outer tail-feather near the base increases on the second and third, on the latter leaving the end only with an oblique white patch. The bands on the under surface have a tendency to a transversely cordate and interrupted, rather than a continuous, linear arrangement.

Young birds have the whole top of head red, as in P. scalaris, with or without white at the base of the red. The white nasal tufts and other characters will, however, distinguish them.

This bird, though widely different in appearance from scalaris, may nevertheless, without any violence, be regarded as but one extreme of a species of which the lighter examples of scalaris (bairdi) are the other, the transition towards nuttalli being through var. scalaris, var. graysoni, and var. lucasanus, each in that succession showing a nearer approach to the distinctive features of nuttalli. We have not seen any intermediate specimens, however. The pure white instead of smoky-brown nasal tufts, and their greater development, are the only characters which show a marked difference from the varieties of scalaris; but the other differences are nothing more than an extension of the black markings and restriction of the red in the male, the result of a melanistic tendency in the Pacific region.

Habits. This species was first discovered by Dr. Gambel near Los Angeles, Cal., and described by him in the Proceedings of the Philadelphia Academy. Afterwards, in his paper on the birds of California, published in the Academy’s Journal, mistaking it for the P. scalaris of Wagler, he furnished a fuller description of the bird and its habits, and gave with it illustrations of both sexes. So far as now known, it appears to be confined to the regions in California and Oregon west of the Coast Range, extending as far south as San Diego, representing, in its distribution on the Pacific, the P. borealis of the Atlantic States. One specimen in the Smithsonian collections was obtained on Umpqua River, in Oregon Territory; the others at Santa Clara, San Francisco, Petaluma, Bodega, and Yreka, in California. Dr. Woodhouse says, in his Report on the birds of the Zuñi and Colorado expedition, that he has only seen this bird in California, from which region he has examined numerous specimens. Dr. Heermann, in his Report on the birds of Lieutenant Williamson’s expedition, states that this Woodpecker is occasionally found in the mountains of Northern California, but that it is much more abundant in the valleys. Dr. Gambel found it abundant in California at all seasons. He describes it as having the usual habits of Woodpeckers, familiarly examining the fence-rails and orchard-trees for its insect-fare. He found it breeding at Santa Barbara, and on the 1st of May discovered a nest containing young in the dead stump of an oak, about fifteen feet from the ground. The hole for entrance was remarkably small, but inside appeared large and deep. The parents were constantly bringing insects and larvæ.

Dr. Cooper states that this Woodpecker is quite abundant towards the coast of California, and among the foothills west of the Sierra Nevada. It frequents the oaks and the smaller trees almost exclusively, avoiding the coniferous forests. It is very industrious, and not easily frightened, when engaged in hammering on the bark of trees allowing a very near approach. At other times, when pursued, it becomes more wary and suspicious. April 20, 1862, Dr. Cooper discovered a nest of this bird near San Diego. It was in a rotten stump, and was only about four feet from the ground. He captured the female on her nest, which contained five eggs of a pure pearly whiteness.

These birds are said to remain throughout the year in the valleys, and to migrate very little, if at all. Dr. Cooper has not observed it west of the Coast Range, except near Santa Barbara, nor has he seen any around gardens or orchards. None have been observed north or east of the State. East of the mountains it is replaced by the scalaris.

Mr. Xantus mentions finding a nest containing two eggs in a hole in the Cereus giganteus, about fifteen feet from the ground. The excavation made by the bird was about a foot and a half deep and six inches wide.

This Woodpecker Mr. Ridgway saw only in the Sacramento Valley, where, in June, it appeared to be a common species among the oaks of the plains. He did not learn anything of its habits, but describes its notes as very peculiar, the usual one being a prolonged querulous rattling call, unlike that of any other bird known to him.

Subgenus PHRENOPICUS, BonapPhrenopicus, Bonap. Consp. Vol. Zygod. Ateneo Ital. 1854. (Type, Picus borealis, Vieill.)

Phrenopipo, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. 1863, 70. Same type.

This subgenus is closely related in external form to the preceding, differing in rather longer and more pointed wings and tail, the latter especially, and a very small, short bill. The first quill (excluding the spurious one) is considerably longer than the sixth, not shorter. The tail-feathers are much attenuated at end. The most marked differences in coloration of the type species, P. borealis, consists in the absence of the post-ocular black patch, leaving the whole auricular region white, and in the restriction of the red to a very narrow line on each side, usually concealed.

Some authors place Picus stricklandi of Mexico (Phrenopipo or Xylocopus stricklandi, Cab. and Hein.) in this section, to which it may indeed belong as far as the wing is concerned, but the markings are entirely different.

Picus borealis, VieillRED-COCKADED WOODPECKERPicus borealis, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 66, pl. cxxii.—Stephens, in Shaw’s Gen. Zoöl. IX, 1817, 174.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 96.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863, 201.—Gray, Catal. 1868, 50.—Allen, B. E. Fla. 305.—Sundevall, Consp. 1866, 21. Threnopipo borealis, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 70. Picus querulus, Wilson, Am. Orn. II, 1810, 103, pl. xv, f. 1.—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 21.—Ib. Isis, 1829, 510.—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 12, pl. ccclxxxix.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 254, pl. cclxiv.—Bp. Consp. 1850, 137.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. S. 1863 (southernmost race). Picus (Phrenopicus) querulus, Bp. Consp. Zyg. Aten. Ital. 1854, 8. Picus leucotis, Illiger (fide Lichtenstein in letter to Wagler; perhaps only a catalogue name).—Licht. Verzeich. 1823, 12, No. 81. Picus vieilloti, Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 20.

Sp. Char. Fourth quill (not counting the spurious) longest. First nearer tip of fifth than of sixth, intermediate between the two. Upper parts, with top and sides of the head, black. Back, rump, and scapulars banded transversely with white; quills spotted with white on both webs; middle and greater coverts spotted. Bristles of bill, under parts generally, and a silky patch on the side of the head, white. Sides of breast and body streaked with black. First and second outer tail-feathers white, barred with black on inner web. Outer web of the third mostly white. A short, very inconspicuous narrow streak of silky scarlet on the side of the head a short distance behind the eye, along the junction of the white and black (this is wanting in the female); a narrow short line of white just above the eye. Length, about 7.25; wing, 4.50; tail, 3.25.

Hab. Southern States, becoming very rare north to Pennsylvania.

This species differs from the other banded Woodpeckers, as stated in the diagnosis, in having a large patch of white behind the eye, including the ears and sides of head, and not traversed by a black post-ocular stripe. The bands of the back, as in P. nuttalli, do not reach the nape, nor extend over the upper tail-covert. The white patch occupies almost exactly the same area as the black one in nuttalli; the white space covered by the supra-orbital and malar stripes, and the white patch on side of nape, of the latter species being here black.

According to Mr. Cassin, southern specimens which he distinguishes as P. querulus from P. borealis of Pennsylvania, differ in smaller number of transverse bars on the back, and shorter quills, and in fewer white spots on the wing-coverts and outer primaries. The black band on the back of neck is wider. This therefore exhibits the same tendency to melanism, in more southern specimens, that has been already indicated for P. villosus, scalaris, etc.

Habits. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker has a restricted distribution to the Southeastern Atlantic States, being rarely met with so far north as Pennsylvania. Georgia and Florida are the only localities represented in the Smithsonian collection, though other Southern States not named have furnished specimens. It has been met with as far to the west as Eastern Texas and the Indian Territory, where Dr. Woodhouse speaks of having found them common. (Report of an Expedition down the Zuñi and Colorado Rivers, Zoölogy, p. 89.) Wilson only met with it in the pine woods of North Carolina, Georgia, and South Carolina, and does not appear to have been acquainted with its habits. Audubon speaks of it as being found abundantly from Texas to New Jersey, and as far inland as Tennessee, and as nowhere more numerous than in the pine barrens of Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. He found these birds mated in Florida as early as January, and engaged in preparing a breeding-place in February. The nest, he states, is not unfrequently bored in a decayed stump about thirty feet high. The eggs he describes as smooth and pure white, and as usually four in number, though he has found as many as six in a nest. The young crawl out of their holes before they are able to fly, and wait on the branches to receive the food brought by their parents until they are able to shift for themselves. During the breeding-season the call of these birds is more than usually lively and petulant, and is reiterated through the pine woods where it is chiefly found.

Wilson compares the common call-notes of these birds to the querulous cries of young birds. His attention was first directed to them by this peculiarity. He characterizes the species as restless, active, and clamorous.

Though almost exclusively a Southern species, and principally found south of North Carolina, individuals have been known to wander much farther north. Mr. G. N. Lawrence obtained a specimen of this bird in Hoboken, N. J., opposite New York City.

In quickness of motion this Woodpecker is said to be equalled by very few of the family. Mr. Audubon states that it glides upwards and sideways, along the trunks and branches, on the lower as well as the upper sides of the latter, moving with great celerity, and occasionally uttering a short, shrill, clear cry, that can be heard at a considerable distance. Mr. Audubon kept a wounded one several days. It soon cut its way out of a cage, and ascended the wall of the room as it would a tree, seizing such spiders and insects as it was able to find. Other than this it would take no food, and was set at liberty.

In the stomach of one dissected were found small ants and a few minute coleopterous insects. In Florida it mates in January and nests in February. In the winter it seeks shelter in holes, as also in stormy weather. Mr. Audubon states that it occasionally feeds on grain and on small fruits. Some go to the ground to search for those that have fallen from trees. They are always found in pairs, and during the breeding-season are very pugnacious.

An egg of this species obtained near Wilmington, N. C., by Mr. N. Giles, measures .95 by .70 of an inch. It is pure white, appeared less glossy than the eggs of most Woodpeckers, and was of a more elliptical shape. Another egg of this bird sent to me by Mr. Samuel Pasco of Monticello, Fla., measures .98 by .70 of an inch, being even more oblong in shape, and corresponds also in the absence of that brilliant polish so common in most Woodpeckers.

Subgenus XENOPICUS, BairdXenopicus, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 83. (Type, Leuconerpes albolarvatus, Cass.)

Xenocraugus, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 74. (Same type.)

This section of Picus is not appreciably different in form from Picus villosus, which may be taken as the American type of the genus Picus. The plumage appears softer, however, and the uniformly black body with white head and white patch at base of primaries will readily distinguish it from any allied group.

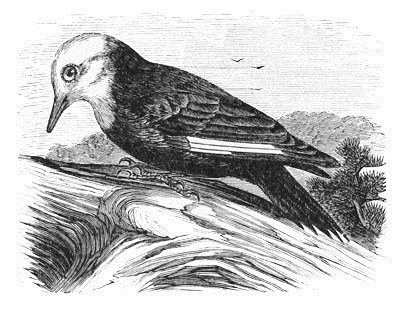

Picus albolarvatus, BairdWHITE-HEADED WOODPECKERLeuconerpes albolarvatus, Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. V, Oct. 1850, 106 (California). Bonap. Consp. Zyg. At. Ital. 1854, 10. Melanerpes albolarvatus, Cassin, J. A. N. Sc. 2d series, II, Jan. 1853, 257, pl. xxii.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Oreg. Route, 9, Rep. P. R. R. VI, 1857. Picus (Xenopicus) albolarvatus, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 96.—Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1863, 202.—Lord, Pr. R. Art. Ins. IV, 1864, 112 (Ft. Colville; nesting).—Cooper & Suckley, 160.—Elliot, Birds N. Am. IX, plate. Picus albolarvatus, Sundevall, Consp. Pic. 29.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 382. Xenocraugus albolarvatus, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 74. Xenopicus albolarvatus, Elliot, Illust. Birds Am. I, pl. xxix.

Picus albolarvatus.

Sp. Char. Fourth and fifth quills equal and longest; tip of first equidistant between sixth and seventh. Entirely bluish-black, excepting the head and neck, and the outer edges of the primaries (except outermost), and the concealed bases of all the quills, which are white. Length, about 9.00; wing, 5.25. Male with a narrow crescent of red on the occiput.

Hab. Cascade Mountains of Oregon and southward into California. Sierra Nevada.

Habits. This very plainly marked Woodpecker, formerly considered very rare, is now known to be abundant in the mountains of Northern California and Nevada, as also in the mountain-ranges of Washington Territory and Oregon. Dr. Cooper found it quite common near the summits of the Sierra Nevada, latitude 39°, in September, 1863, and procured three specimens. Three years previously he had met with it at Fort Dalles, Columbia River. He thinks that its chief range of distribution will be found to be between those two points. He also found it as far north as Fort Colville, in the northern part of Washington Territory, latitude 49°. He characterizes it as a rather silent bird.

Dr. Newberry only met with this bird among the Cascade Mountains, in Oregon, where he did not find it common.

Mr. J. G. Bell, who first discovered this species, in the vicinity of Sutter’s Mills, in California, on the American River, represents it as frequenting the higher branches of the pines, keeping almost out of gunshot range. Active and restless in its movements, it uttered at rare intervals a sharp and clear note, while busily pursuing its search for food.

Mr. John K. Lord states that the only place in which he saw this very rare bird was in the open timbered country about the Colville Valley and Spokan River. He has observed that this Woodpecker almost invariably haunts woods of the Pinus ponderosa, and never retires into the thick damp forest. It arrives in small numbers at Colville, in April, and disappears again in October and November, or as soon as the snow begins to fall. Although he did not succeed in obtaining its eggs, he saw a pair nesting in the month of May in a hole bored in the branch of a very tall pine-tree. It seldom flies far, but darts from tree to tree with a short jerking flight, and always, while flying, utters a sharp, clear, chirping cry. Mr. Ridgway found it to be common in the pine forests of the Sierra Nevada, in the region of the Donner Lake Pass. It was first observed in July, at an altitude of about five thousand feet, on the western slope of that range, where it was seen playing about the tops of the tallest dead pines. On various occasions, at all seasons, it was afterwards found to be quite plentiful on the eastern slope, in the neighborhood of Carson City, Nevada. Its habits and manners are described as much like those of the P. harrisi, but it is of a livelier and more restless disposition. Its notes have some resemblance to those of that species, but are of a more rattling character. It is easily recognized, when seen, by its strikingly peculiar plumage.

Genus PICOIDES, LacepPicoides, Lacep. Mem. Inst. 1799. (Type, Picus tridactylus.)

Tridactylia, Steph. Shaw, Gen. Zoöl. 1815.

Apternus, Sw. F. B. A. II, 1831, 311.

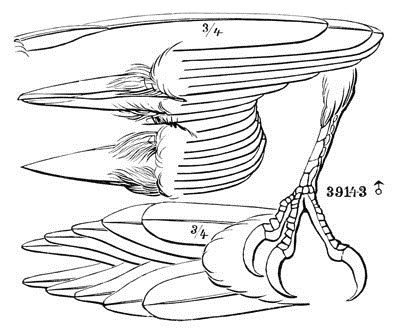

Picoides arcticus.

39143 ♂

Gen. Char. Bill about as long as the head, very much depressed at the base; the outlines nearly straight; the lateral ridge at its base much nearer the commissure than the culmen, so as to bring the large, rather linear nostrils close to the edge of the commissure. The gonys very long, equal to the distance from the nostrils to the tip of the bill. Feet with only three toes, the first or inner hinder one being wanting; the outer lateral a little longer than the inner, but slightly exceeded by the hind toe, which is about equal to the tarsus. Wings very long, reaching beyond the middle of the tail, the tip of the first quill between those of sixth and seventh. Color black above, with a broad patch of yellow on the crown; white beneath, transversely banded on the sides. Quills, but not wing-coverts, with round spots. Lateral tail-feathers white, without bands on exposed portion, except in European specimens.

The peculiarities of this genus consist in the absence of the inner hind toe and the great depression of the bill. The figure above fails to represent the median ridge of the bill as viewed from above.

Common Characters. The American species of Picoides agree in being black above and white beneath; the crown with a square yellow patch in the male; a white stripe behind the eye, and another from the loral region beneath the eye; the quills (but not the coverts) spotted with white; the sides banded transversely with black. The diagnostic characters (including the European species) are as follows:—

Species and VarietiesP. arcticus. Dorsal region without white markings; no supraloral white stripe or streak, nor nuchal band of white. Four middle tail-feathers wholly black; the next pair with the basal half black; the outer two pairs almost wholly white, without any dark bars. Entire sides heavily banded with black; crissum immaculate; sides of the breast continuously black. ♂. Crown with a patch of yellow, varying from lemon, through gamboge, to orange, and not surrounded by any whitish markings or suffusion. ♀. Crown lustrous black, without any yellow, and destitute of white streaks or other markings. Wing, 4.85 to 5.25; tail, 3.60; culmen, 1.40 to 1.55. Hab. Northern parts of North America. In winter just within the northern border of the United States, but farther south on high mountain-ranges.

P. tridactylus. Dorsal region with white markings, of various amount and direction; a more or less distinct supraloral white streak or stripe, and a more or less apparent nuchal band of the same. Four to six middle tail-feathers entirely black; when six, the remainder are white, with distinct black bars to their ends; when four, they are white without any black bars, except occasionally a few toward the base. Sides always with black streaks or markings, but they are sometimes very sparse; crissum banded with black, or immaculate; sides of the breast not continuously black. ♂. Crown with a patch of gamboge, amber, or sulphur-yellow, surrounded by a whitish suffusion or markings. ♀. Crown without any yellow, but distinctly streaked, speckled, or suffused with whitish (very seldom plain black).

a. Six middle tail-feathers wholly black. Europe and Asia.

Sides and crissum heavily barred with black (black bars about as wide as the white ones).

Back usually transversely spotted with white; occasionally longitudinally striped with the same in Scandinavian examples. Wing, 4.80 to 5.10; tail, 3.80 to 4.00; culmen, 1.20 to 1.35. Hab. Europe … var. tridactylus.127

Sides and crissum almost free from black bars; black bars on the outer tail-feathers very much narrower than the white.

Back always (?) striped longitudinally with white. Wing, 4.70 to 4.75; tail, 3.65 to 3.90; culmen, 1.20 to 1.35. Hab. Siberia and Northern Russia … var. crissoleucus.128