полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

b. Four middle tail-feathers, only, wholly black. North America.

Sides heavily barred with black, but crissum without bars, except beneath the surface. Three outer tail-feathers without black bars, except sometimes on the basal portion of the inner webs. Wing, 4.40 to 5.10; tail, 3.40 to 3.70; culmen, 1.10 to 1.25.

Back transversely spotted or barred with white. Hab. Hudson’s Bay region; south in winter to northern border of Eastern United States … var. americanus.

Back longitudinally striped with white at all seasons. Hab. Rocky Mountains; north to Alaska … var. dorsalis.

Picoides arcticus, GrayTHE BLACK-BACKED THREE-TOED WOODPECKERPicus (Apternus) arcticus, Sw. F. Bor. Am. II, 1831, 313. Apternus arcticus, Bp. List, 1838.—Ib. Consp. 1850, 139.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Oreg. Route, 91, Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VI, 1857. Picus arcticus, Aud. Syn. 1839, 182.—Ib. Birds Amer. VI, 1842, 266, pl. cclxviii.—Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 691.—Sundevall, Consp. I, 1866, 15. Picus tridactylus, Bon. Am. Orn. II, 1828, 14, pl. xiv, f. 2.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 198, pl. cxxxii. Tridactylia arctica, Cab. & Hein. Picoides arcticus, Gray, Gen.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 98.—Lord, Pr. R. Art. Inst. Woolwich, IV, 1864, 112 (Cascade Mountains).—Cooper, Pr. Cal. Ac. Sc. 1868 (Lake Tahoe and Sierra Nevada).—Samuels, 94.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 384.

Picoides arcticus.

Sp. Char. Above entirely uniform glossy bluish-black; a square patch on the middle of the crown saffron-yellow, and a few white spots on the outer edges of both webs of the primary and secondary quills. Beneath white, on the sides of whole body, axillars, and inner wing-coverts banded transversely with black. Crissum white, with a few spots anteriorly. A narrow concealed white line from the eye a short distance backwards, and a white stripe from the extreme forehead (meeting anteriorly) under the eye, and down the sides of the neck, bordered below by a narrow stripe of black. Bristly feathers of the base of the bill brown; sometimes a few gray intermixed. Exposed portion of two outer tail-feathers (first and second) white; the third obliquely white at end, tipped with black. Sometimes these feathers with a narrow black tip.

Hab. Northern North America; south to northern borders of United States in winter. Massachusetts (Maynard, B. E. Mass., 1870, 129). Sierra Nevada, south to 39°. Lake Tahoe (Cooper); Carson City (Ridgway).

This species differs from the other American three-toed Woodpeckers chiefly in having the back entirely black. The white line from the eye is usually almost imperceptible, if not wanting entirely. Specimens vary very little; one from Slave Lake has a longer bill than usual, and the top of head more orange. The size of the vertex patch varies; sometimes the frontal whitish is inappreciable. None of the females before me have any white spots in the black of head, as in that of americanus.

The variations in this species are very slight, being chiefly in the shade of the yellow patch on the crown, which varies from a sulphur tint to a rich orange. Sometimes there is the faintest trace of a whitish post-ocular streak, but usually this is wholly absent. Western and Eastern examples appear to be identical.

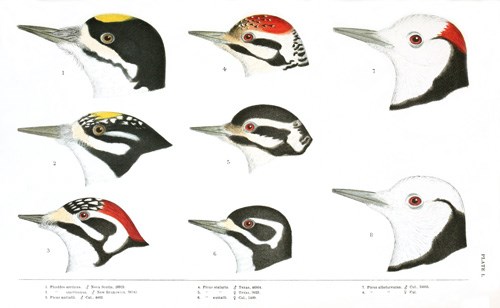

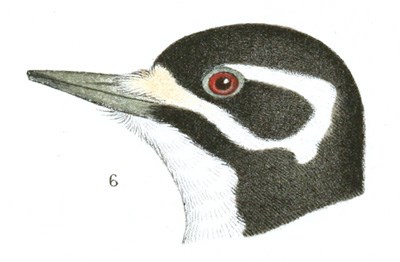

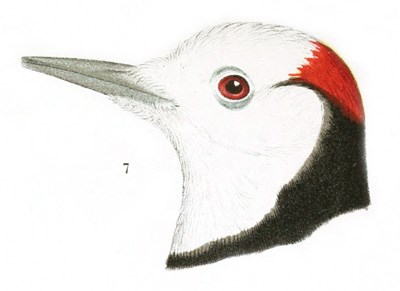

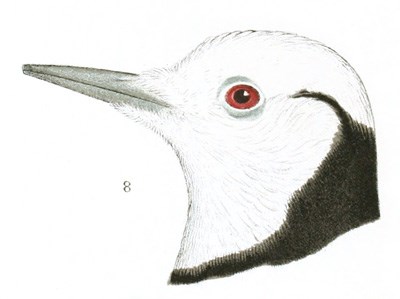

PLATE L.

1. Picoides arcticus. ♂ Nova Scotia, 26923.

2. Picoides americanus. ♂ New Brunswick, 39143.

3. Picus nuttalli. ♂ Cal., 4482.

4. Picus scalaris. ♂ Texas, 46804.

5. Picus scalaris. ♀ Texas, 9933.

6. Picus nuttalli. ♀ Cal., 5400.

7. Picus albolarvatus. ♂ Cal., 16066.

8. Picus albolarvatus ♀ Cal.

Habits. This species has a well-defined and extended distribution, from the Pacific to the Atlantic, and from the northern portions of the United States to the extreme Arctic regions. In the United States it has been found as far south as Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio, but rarely; and, so far as I am aware, it is a winter visitant only to any but the extreme northern portions of the Union, except along the line of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada. Audubon says it occurs in Northern Massachusetts, and in all portions of Maine that are covered by forests of tall trees, where it constantly resides. He saw a few in the Great Pine Forest of Pennsylvania, and Dr. Bachman noticed several in the neighborhood of Niagara Falls, and was of the opinion that it breeds in the northern part of New York. The same writer describes the nesting-place of the Arctic Woodpecker as generally bored in the body of a sound tree, near its first large branches. He observed no particular choice as to the timber, having seen it in oaks, pines, etc. The nest, like that of most of this family, is worked out by both sexes, and requires fully a week for its completion. Its usual depth is from twenty to twenty-four inches. It is smooth and broad at the bottom, although so narrow at its entrance as to appear scarcely sufficient to enable one of the birds to enter it. The eggs are from four to six, rather rounded and pure white. Only one brood is raised in the season. The young follow their parents until the autumn. In the southern districts where these Woodpeckers are found, their numbers are greatly increased in the winter by accessions from the North.

Dr. Cooper found this species quite numerous, in September, in the vicinity of Lake Tahoe and the summits of the Sierra Nevada, above an altitude of six thousand feet. From thence this bird has a northern range chiefly on the east side of these mountains and of the Cascade Range. None were seen near the Lower Columbia. At the lake they were quite fearless, coming close to the hotel, and industriously rapping the trees in the evening and in the early morning. Farther north Dr. Cooper found them very wild, owing probably to their having been hunted by the Indians for their skins, which they consider very valuable. He noticed their burrows in low pine-trees near the lake, where he had no doubt they also raise their young. Dr. Cooper has always found them very silent birds, though in the spring they probably have more variety of calls. The only note he heard was a shrill, harsh, rattling cry, quite distinct from that of any other Woodpecker.

The flight of this Woodpecker is described as rapid, gliding, and greatly undulated. Occasionally it will fly to quite a distance before it alights, uttering, from time to time, a loud shrill note.

Professor Verrill says this bird is very common in Western Maine, in the spring, fall, and winter, or from the middle of October to the middle or end of March. It is not known to occur there in the summer. Near Calais a few are seen, and it is supposed to breed, but is not common. In Massachusetts it is only a rare and accidental visitant, occurring usually late in winter or in March. Two were taken near Salem in November. It is also a rare winter visitant near Hamilton in Canada.

Mr. Ridgway met with but a single individual of this species during his Western explorations. This was shot in February, near Carson City, Nevada; it was busily engaged in pecking upon the trunk of a large pine, and was perfectly silent.

Mr. John K. Lord obtained a single specimen of this bird on the summit of the Cascade Mountains. It was late in September, and getting cold; the bird was flying restlessly from tree to tree, but not searching for insects. Both when on the wing and when clinging to a tree, it was continually uttering a shrill, plaintive cry. Its favorite tree is the Pinus contorta, which grows at great altitudes. It is found chiefly on hill-tops, while in the valleys and lower plains it is replaced by the Picoides hirsutus.

Eggs of this species were obtained by Professor Agassiz on the northern shore of Lake Superior. They were slightly ovate, nearly spherical, rounded at one end and abruptly pointed at the other, of a crystal whiteness, and measured .91 of an inch in length by .70 in breadth.

An egg received from Mr. Krieghoff is small in proportion to the size of the bird, nearly spherical in form, and of a uniform dull-white color. It measures .92 of an inch in length by .76 in breadth.

Picoides tridactylus, var. americanus, BrehmTHE WHITE-BACKED THREE-TOED WOODPECKERPicus hirsutus, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 68, pl. cxxiv (European specimen).—Wagler, Syst. Av. 1827, No. 27 (mixed with undulatus).—Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 184, pl. ccccxvii.—Ib. Birds Amer. IV, 1842, pl. cclxix.—Nuttall, Man. I, (2d ed.,) 1840, 622. Apternus hirsutus, Bon. List, Picoides hirsutus, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 98.—Samuels, 95. ? Picus undulatus, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 69 (based on Pl. enl. 553, fictitious species?) Picus undatus, Temm. Picus undosus, Cuv. R. A. 1829, 451 (all based on same figure). Tridactylia undulata, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 28. Picus tridactylus, Sw. F. Bor. Am. 1831, 311, pl. lvi. Picoides americanus, Brehm, Vögel Deutschlands, 1831, 195.—Malherbe, Mon. Picidæ, I, 176, pl. xvii, 36.—Sclater, Catal.—Gray, Cat. Br. Mus. III, 3, 4, 1868, 30. Apternus americanus, Swainson, Class. II, 1837, 306. Picus americanus, Sundevall, Consp. Av. Picin. 1866, 15. Picoides dorsalis, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 100, pl. lxxxv, f. 1.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870 (under P. americanus). Tridactylia dorsalis, Cab. & Hein. Picus dorsalis, Sundevall, Consp. 1866, 14.

Sp. Char. Black above. The back markings of white, transverse in summer, and longitudinal in winter; these extend to the rump, which is sometimes almost wholly white. A white line from behind the eye, widening on the nape, and a broader one under the eye from the loral region, but not extending on the forehead; occiput and sides of head uniform black. Quills, but not coverts, spotted on both webs with white, seen on inner webs of inner secondaries. Under parts, including crissum, white; the sides, including axillars and lining of wing, banded transversely with black. Exposed portion of outer three tail-feathers white; that of third much less, and sometimes with a narrow tip of black. Upper tail-coverts sometimes tipped with white, and occasionally, but very rarely, banded with the same. Top of the head spotted, streaked, or suffused with white; the crown of the male with a yellow patch. Nasal bristles black, mixed with gray. Female with the whole top of head usually spotted with white, very rarely entirely black.

Hab. Arctic regions of North America; southward in the Rocky Mountains to Fort Buchanan; northern border of the Eastern United States, in winter (Massachusetts, Maynard).

This species varies considerably in its markings, especially in the amount of white above. The head is sometimes more coarsely spotted with white than in the average; very rarely are the white spots wanting, leaving merely the broad malar and interrupted post-ocular stripe. The rictal black stripe is sometimes much obscured by white. In typical specimens from the Hudson Bay and Labrador Provinces, which seem to be darkest, the feathers of the centre of the back have three transverse bars of white (one of them terminal), rather narrower than the intermediate black bars; the basal white ones disappearing both anteriorly and posteriorly, leaving but two. In specimens from the Mackenzie River district there is a greater development of white; the white bands being broader than the black, and sometimes extending along the shafts so as to reduce the black bars to pairs of spots. The next step is the disappearance of these spots on one side or the other, or on both, leaving the end of the feathers entirely white, especially anteriorly, where the back may have a longitudinal stripe of white, as in Picus villosus. Usually, however, in this extreme, the upper tail-coverts remain banded transversely. In all the specimens from the Rocky Mountains of the United States, especially Laramie Peak, this white back, unbarred except on the rump, is a constant character, and added to it we have a broad nuchal patch of white running into that of the back and connected with the white post-ocular stripe. The bands, too, on the sides of the body, are less distinct. It was to this state of plumage that the name of P. dorsalis was applied, in 1858, and although in view of the connecting links it may not be entitled to consideration as a distinct race, this tendency to a permanence of the longitudinal direction of the white markings above seems to be especially characteristic of the Rocky Mountain region, appearing only in winter birds from elsewhere. This same character prevails in all the Rocky Mountain specimens from more northern regions, including those from Fort Liard, and in only one not found in that region, namely, No. 49,905, collected at Nulato by Mr. Dall. Here the middle of the back is very white, although the nuchal band is less distinct. Other specimens from that locality and the Yukon River generally, as also from Kodiak, distinctly show the transverse bars.

In one specimen (29,126) from the Mackenzie River, all the upper tail-coverts are banded decidedly with white, and the wing-coverts spotted with the same. Even the central tail-feathers show white scallops. The back is, however, banded transversely very distinctly, not longitudinally.

P. americanus in all stages of color is distinguished from arcticus by the white along the middle of the back, the absence of distinct frontal white and black bands, more numerous spots of white on the head, etc. The inner webs of inner secondaries are banded with white, not uniform black. The maxillary black stripe is rather larger than the rictal white one, not smaller. The size is decidedly smaller. Females almost always have the top of head spotted with white instead of uniform black, which is the rule in arcticus.

It is probable that the difference in the amount of white on the upper parts of this species is to some extent due to age and season, the winter specimens and the young showing it to the greatest degree. Still, however, there is a decided geographical relationship, as already indicated.

This race of P. tridactylus can be easily distinguished from the European form of Northern and Alpine Europe by the tail-feathers; of these, the outer three are white (the rest black) as far as exposed, without any bands; the tip of the third being white only at the end. The supra-ocular white stripe is very narrow and scarcely appreciable; the crissum white and unbanded. The back is banded transversely in one variety, striped longitudinally in the other. In P. tridactylus the outer two feathers on each side are white, banded with black; the outer with the bands regular and equal from base; the second black, except one or two terminal bands. The crissum is well banded with black; the back striped longitudinally with white; the supra-ocular white stripe almost as broad as the infra-ocular. P. crisoleucus, of Siberia, is similar to the last, but differs in white crissum, and from both species in the almost entire absence of dark bands on the sides, showing the Arctic maximum of white.

We follow Sundevall in using the specific name americanus, Brehm, for this species, as being the first legitimately belonging to it. P. hirsutus of Vieillot, usually adopted, is based on a European bird, and agrees with it, though referred by the author to the American. The name of undulatus, Vieillot, selected by Cabanis, is based on Buffon’s figure (Pl. enl. 553) of a bird said to be from Cayenne, with four toes; the whole top of the head red from base of bill to end of occiput, with the edges of the dorsal feathers narrowly white, and with the three lateral tail-feathers regularly banded with black, tipped with red; the fourth, banded white and black on outer web, tipped with black. None of those features belong to the bird of Arctic America, and the markings answer, if to either, better to the European.

Habits. This rare and interesting species, so far as has been ascertained, is nowhere a common or well-known bird. It is probably exclusively of Arctic residence, and only occasionally or very rarely is found so far south as Massachusetts. In the winter of 1836 I found a specimen exposed for sale in the Boston market, which was sent in alcohol to Mr. Audubon. Two specimens have been taken in Lynn, by Mr. Welch, in 1868. They occur, also, in Southern Wisconsin in the winter, where Mr. Kumlien has several times, in successive winters, obtained single individuals.

Sir John Richardson states that this bird is to be met with in all the forests of spruce and fir lying between Lake Superior and the Arctic Sea, and that it is the most common Woodpecker north of Great Slave Lake, whence it has frequently been sent to the Smithsonian Institution. It is said to greatly resemble P. villosus in habits, except that it seeks its food principally upon decaying trees of the pine tribe, in which it frequently makes holes large enough to bury itself. It is not migratory.

Genus SPHYROPICUS, BairdPilumnus, Bon. Consp. Zygod. Ateneo Italiano, May, 1854. (Type P. thyroideus) preoccupied in crustaceans.

Sphyropicus, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 101. (Type, Picus varius,) Linn., Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 52 (anatomy).

Cladoscopus, Cab. & Hein. Mus. Hein. IV, 2, 1863, 80. (Type, P. varius.)

Sphyropicus nuchalis.

20511 ♀

Gen. Char. Bill as in Picus, but the lateral ridge, which is very prominent, running out distinctly to the commissure at about its middle, beyond which the bill is rounded without any angles at all. The culmen and gonys are very nearly straight, but slightly convex, the bill tapering rapidly to a point; the lateral outline concave to very near the slightly bevelled tip. Outer pair of toes longest; the hinder exterior rather longest; the inner posterior toe very short, less than the inner anterior without its claw. Wings long and pointed; the third, excluding the spurious, longest. Tail-feathers very broad, abruptly acuminate, with a very long linear tip. Tongue scarcely extensible.

The genus Sphyropicus, instituted in 1858, proves to be so strongly marked in its characters that Dr. Coues proposes to make it the type of a distinct subfamily, Sphyropicinæ (Pr. Phil. Acad. 1866, 52). In addition to the peculiarities already indicated, there is a remarkable feature in the tongue, which, according to Dr. Coues, Dr. Hoy, Dr. Bryant, and others, is incapable of protrusion much beyond the tip of the bill, or not more than the third of an inch. Dr. Coues states that the apo-hyal and cerato-hyal elements of the hyoid bone do not reach back much beyond the tympano-maxillary articulation, instead of extending round, as in Picus, over the occiput to the top of the cranium, or even curving into an osseous groove around the orbit. The basihyals supporting the tongue are shorter and differently shaped. The tongue itself is short and flattened, with a superior longitudinal median groove and a corresponding inferior ridge; the tip is broad and flattened and obtusely rounded, and with numerous long and soft bristly hairs. This is, of course, very different from the long, extensile, acutely pointed tongue of other Woodpeckers, with its tip armed with a few strong, sharp, short, recurved barbs.

Dr. Hoy and Dr. Coues maintain that the food of these Woodpeckers consists mainly of the cambium or soft inner bark of trees, which is cut out in patches sometimes of several inches in extent, and usually producing square holes in the bark, not rounded ones. As may be supposed, such proceedings are very injurious to the trees, and justly call down the vengeance of their proprietors. This diet is varied with insects and fruits, when they can be had, but it is believed that cambium is their principal sustenance.

This strongly marked genus appears to be composed of two sections and three well-defined species; the first being characterized by having the back variegated with whitish, and the jugulum with a sharply defined crescentic patch of black, though the latter is sometimes concealed by red, when the whole head and neck are of the latter color, and the sharply defined striped pattern of the cephalic regions, seen in the normal plumage, obliterated. Comparing the extreme conditions of plumage to be seen in this type, as in the females of varius and of ruber, the differences appear wide indeed, and few would entertain for a moment a suspicion of their specific identity; yet upon carefully examining a sufficiently large series of specimens, we find these extremes to be connected by an unbroken transition, and are thus led to view these different conditions as manifestations of a peculiar law principally affecting a certain color, which leads us irresistibly to the conclusion that the group which at first seemed to compose a section of the genus is in reality only an association of forms of specific identity. Beginning with the birds of the Atlantic region (S. varius), we find in this series the minimum amount of red; indeed, many adult females occur which lack this color entirely, having not only the whole throat white, but the entire pileum glossy-black; usually, however, the latter is crimson. In adult males from this region the front and crown are always crimson, sharply defined, and bordered laterally and posteriorly with glossy-black; and below the black occipital band is another of dirty white; the crimson of the throat is wholly confined between the continuous broad, black malar stripes, and there is no tinge of red on the auriculars; there is a broad, sharply defined stripe of white beginning with the nasal tufts, passing beneath the black loral and auricular stripe, and continuing downward into the yellowish of the abdomen, giving the large, glossy-black pectoral area a sharply defined outline; the dirty whitish nuchal band is continued forward beneath the black occipital crescent to above the middle of the eye. The pattern just described will be found in ninety-nine out of a hundred specimens from the Eastern Province of North America (also the West Indies and whole of Mexico); but a single adult male, from Carlisle, Penn. (No. 12,071, W. M. Baird), has the whitish nuchal band distinctly tinged with red, though differing in this respect only, while an adult female, from Washington, D. C. (No. 12,260, C. Drexler), has the lower part of the throat much mixed with red.

Taking next the specimens from the Rocky Mountains and Middle Province of the United States (S. nuchalis), we find that all the specimens possess both these additional amounts of the red, there being always a red, instead of dirty-white, nuchal crescent, while in the female the lower part of the throat is always more or less red; in addition, the male has the red of the throat reaching laterally to the white stripe, thus interrupting the black malar one, which is always unbroken in the eastern form; and in addition, the auriculars are frequently mixed with red. Proceeding towards the Columbia River, we find the red increasing, or escaping the limits to which it is confined in the normal pattern, staining the white and black areas in different places, and tingeing the whitish which borders the black pectoral area.