полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

The females are quite similar, but lack the white patch of the tail, have more numerous rufous spots on quills, and are perhaps more fulvous in general appearance. Young birds, however, would hardly be recognized as the same, except when taken with adults, owing to the predominance of a pale cinnamon shade above, and a decided tinge of the same on all the white and gray markings. Nearly all the primaries have a border of this color.

The variety acutipennis of South America (see synopsis) is very similar, differing merely in smaller dimensions.

Habits. The Texan Night-Hawk occurs in the valley of the Rio Grande from Texas on the east, through New Mexico, Arizona, Southern California, and Cape San Lucas. It is found in the northern provinces of Mexico during the summer months, and thence southward to Central America. It was found at Dueñas, in Guatemala, by Mr. Salvin, and also at Coban. Mr. Xantus found it breeding at Cape San Lucas in May.

This species was first added to our fauna by Mr. Lawrence, in 1851, as a bird of Texas, supposed to be C. brasilianus, and in 1856 described by the same writer as a new species.

According to Dr. Cooper, it makes its first appearance at Fort Mohave by the 17th of April, and soon after becomes quite numerous, hunting in companies after sunset, and hiding during the day on the ground under low bushes. By the 25th of May they had all paired, but continued nearly silent, making only a low croaking when approached. They flew in the manner of the common species, but seemed to sail in rather smaller circles. Dr. Cooper found them as far west as the Coast Mountains.

Dr. Coues states that this species is common in the Colorado Valley, even farther north than the latitude of Fort Whipple. It was not, however, met with by him at that port, nor indeed for some fifty miles to the south of it, and then only in the summer. He adds that it extends from the Rio Grande Valley westward to the Pacific. It was found abundant at Cape St. Lucas by Dr. Xantus.

Mr. Dresser found it very common at Matamoras during the summer season, and thence to San Antonio and to the eastward of that place. At San Antonio, in the spring, he first noticed them on the 2d of May, when he saw seven or eight flying about at noonday. A few days later they had become very numerous. They remained about San Antonio until the end of September, and soon after disappeared. He noticed none later than the first week in October.

Mr. J. H. Clark met with this species at Ringgold Barracks, Texas, in June. They were to be seen sitting about in the heat of the day, at which time they could be easily approached. During the hottest days they did not sally forth in quest of food until late in the evening. On one occasion, near El Paso, Mr. Clark saw these birds congregated in such quantities over a mud-hole from which were issuing myriads of insects, that he felt that the discharge among them of mustard-seed shot would involve a wanton destruction. This species is not known, according to his account, to make a swoop in the manner of the common species. It does not utter the same hoarse sounds, nor does it ever fly so high.

Among the notes of the late Dr. Berlandier, of Matamoras, we find references to this species, to which he gives the common name of Pauraque, and in his collection of eggs are many that unquestionably are those of this bird, and which are, in all respects but size, in close affinity to the eggs of the common Night-Hawk. These eggs measure 1.18 inches in length by .87 of an inch in breadth. Their ground-color, seen through a magnifying glass, is of clear crystal whiteness, but is so closely covered by overlaying markings as not to be discernible to the eye. They are marked over the entire surface with small irregular confluent spots and blotches, which are a blending of black, umber, and purplish-gray markings. These combinations give to the egg the appearance of a piece of polished marble of a dark gray color. They are both smaller and of a lighter color than those of the common eastern bird.

Genus ANTROSTOMUS, GouldAntrostomus, Gould, Icones Avium, 1838. (Type, Caprimulgus carolinensis, Gm.)

Antrostomus nuttalli.

Gen. Char. Bill very small, with tubular nostrils, and the gape with long, stiff, sometimes pectinated bristles projecting beyond the end of the bill. Tarsi moderate, partly feathered above. Tail broad, rounded; wings broad and rounded; first quill shorter than third; plumage soft and lax. Habit nocturnal.

In what the genus Antrostomus really differs from Caprimulgus proper, we are quite unable to say, as in the many variations of form of both New and Old World species of these two divisions respectively, it is said to be not difficult to find species in each, almost identical in form. In the want of suitable material for comparison, we shall follow Sclater in using Antrostomus for the New World species.

Species and Varieties. 105A. Bristles of gape with lateral filaments. Light tail-spaces confined to inner web of feathers.

Dark markings on crown longitudinal. Ochraceous or white gular collar in form of a narrow band across jugulumA. carolinensis. Throat ochraceous, with sparse, narrow, transverse bars of black; jugular collar more whitish, with broader but more distant black bars. Crissum barred, and inner webs of primaries with black prevailing. Wing, 8.90; tail, 6.30. Hab. Louisianian region of the Eastern Province of United States (Florida and the Carolinas to Arkansas). Costa Rica.

B. Bristles of gape without lateral filaments; light tail-spaces covering both webs.

a. Throat black, with sparse, narrow, transverse bars of pale brown. Crissum barred, and inner webs of primaries with black greatly predominating.

A. macromystax. Crown pale brown and whitish very coarsely mottled with dusky; lower parts clouded with whitish, in conspicuous contrast with the ground color. Light tail patch restricted to less than terminal third, and decreasing in breadth toward the middle feathers. Bristles of gape enormously long and stout; bill compressed, nostrils large.

White patch on end of tail confined to three outer feathers, and decreasing very rapidly in extent to the inner. Wing, 6.60; tail, 5.30; rictal bristles, 1.40. Hab. Mexico (Mirador, La Parada) … var. macromystax.106

White patch on end of tail, on four outer feathers, and just appreciably decreasing in extent toward the inner. Wing, 7.00; tail, 5.50; rictal bristles, 2.00. Hab. Cuba … var. cubanensis.107

A. vociferus. Crown ash, finely mottled or minutely sprinkled with dusky; lower parts without whitish cloudings. White tail-patch covering more than terminal half, and decreasing in breadth toward the outer feather. Bristles of gape moderate, slender; bill weaker, less compressed, and nostrils smaller. Wing, 6.40; tail, 5.10; rictal bristles, 1.50 or less. Hab. Eastern Province of North America, south to Guatemala.

Dark markings of crown transverse. Gular collar pure white, covering nearly whole throatb. Throat pure white, without any markings. Crissum immaculate; inner webs of primaries with ochraceous very largely predominating.

A. nuttalli. White space of tail occupying about the terminal fourth, or less, on three feathers, and gradually decreasing inwardly. Wing, 5.75; tail, 3.90; rictal bristles less than 1.00. Hab. Western Province of United States, from the Plains to the Pacific.

Antrostomus carolinensis, GouldCHUCK-WILL’S WIDOWCaprimulgus carolinensis, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 1028.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 273, pl. lii; V, 1839, 401.—Ib. Birds Am. I, 1840, 151, pl. xli.—Warthausen, Cab. J. 1868, 368 (nesting). Antrostomus carolinensis, Gould, Icones Avium, 1838?—Cassin, Illust. N. Am. Birds, I, 1855, 236.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 147.—Allen, B. Fla. 300. Caprimulgus rufus, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. I, 1807, 57, pl. xxv (♀). Caprimulgus brachypterus, Stephens, Shaw’s Zoöl. X, I, 1825? 150. Short-winged Goatsucker, Pennant, Arctic Zoöl. II, 1785, 434.

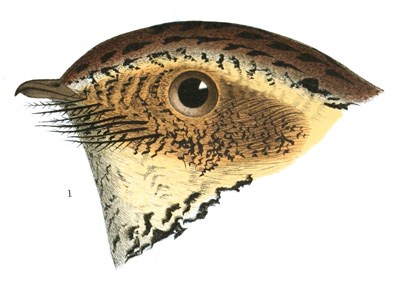

Antrostomus carolinensis.

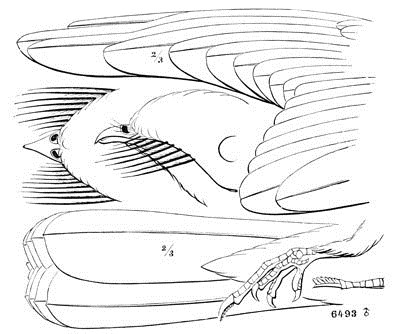

6493 ♂

Sp. Char. Bristles of the bill with lateral filaments. Wing nearly nine inches long. Top of the head finely mottled reddish-brown, longitudinally streaked with black. The prevailing shade above and below pale rufous. Terminal two-thirds of the tail-feathers (except the four central) rufous white; outer webs of all mottled, however, nearly to the tips. Female without the white patch on the tail. Length, 12.00; wing, 8.50.

Hab. South Atlantic and Gulf States to Veragua; Cuba in winter. Cuba (Caban. J. IV, 6, winter); San Antonio, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 70, breeds); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 120); Veragua (Salvin, P. Z. S. 1870, 303).

This, according to Sclater, is the largest of the Antrostomi and the only species with lateral filaments to the bristles of the mouth.

The extent of the white spaces on the inner webs of tail-feathers varies with the individual, but in none does it occupy less than the terminal half.

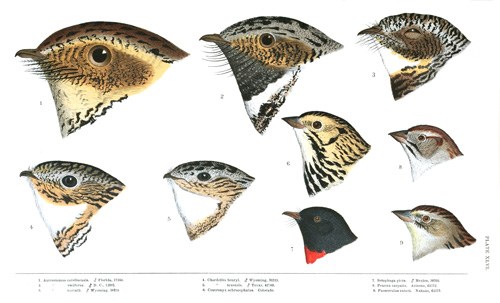

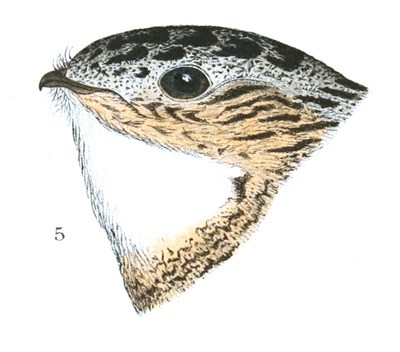

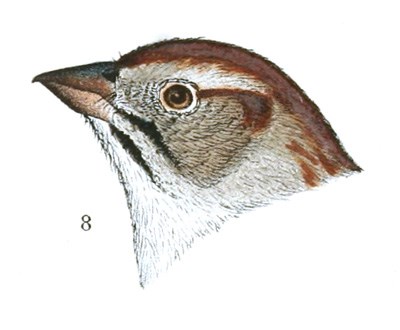

PLATE XLVI.

1. Antrostomus carolinensis. ♂ Florida, 17160.

2. Antrostomus vociferus. ♂ D. C., 12085.

3. Antrostomus nuttalli. ♂ Wyoming, 38324.

4. Chordeiles henryi. ♂ Wyoming, 38323.

5. Chordeiles texensis. ♂ Texas, 42189.

6. Centronyx ochrocephalus. Colorado.

7. Setophaga picta. ♂ Mexico, 30705.

8. Peucæa carpalis. Arizona, 62372.

9. Passerculus caboti. Nahant, 62373.

The A. rufus (Caprimulgus rufus, Bodd. et Gmel. ex Pl. Enl. 735 (?); Antrostomus r. Sclater, P. Z. S. 1866, 136; A. rutilus, Burm. Syst. Ueb. II, 385) and A. ornatus (Scl. P. Z. S. 1866, 586, pl. xlv), of South America, appear to be the nearest relatives of this species, agreeing very closely in coloration; but both have the rictal bristles simple, without lateral filaments, and would thus seem to be distinct species. In the latter, the white spaces of the tail are found only on the second and third feathers, instead of on the outer three, while the former is said to have no such markings at all.

Habits. The exact extent of the geographical range of this species is not very clearly defined. Rarely anywhere a very abundant species, it is more common throughout Florida than in any other State. It is also found, more or less frequently, in the States of Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Dr. Woodhouse mentions finding it common in the Creek and Cherokee countries of the Indian Territory, and also extending into Texas and New Mexico. Mr. Dresser noticed several of this species on the Medina River, in Texas, April 28, and afterwards in May. On the 18th of the same month he again found it very numerous at New Braunfels, and also, on the 20th, at Bastrop. Dr. Heermann states that these birds visit the neighborhood of San Antonio in the spring, and remain there to raise their young.

James River, Virginia, has been assigned as the extreme northern limit of its migrations, but I can find no evidence of its occurring so far north, except as an accidental visitant. Wilson, indeed, claims to have met with it between Richmond and Petersburg, and also on the Cumberland River. Dr. Bachman states that it is not a common bird even in the neighborhood of Charleston. Mr. Audubon, who claimed to be a very close and careful observer of the habits of this species, states that it is seldom to be met with beyond the then southern limits of the Choctaw nation, in Mississippi, or the Carolinas on the Atlantic coast.

I have been informed by Dr. Kollock that these birds are rather common at Cheraw, in the northern part of South Carolina. Dr. Bryant found them quite abundant near Indian River, in Florida, though he makes no mention of them in his paper on the birds of that State. Mr. Cassin informed me that Colonel McCall met with this bird in New Mexico. Lembeye includes it among the birds of Cuba, but in reality refers to cubanensis.

These birds, according to Mr. Audubon, are not residents, but make their appearance within the United States about the middle of March. They are nocturnal in their habits, remaining silent and keeping within the shady recesses of the forests during the daytime. As soon as the sun has disappeared and the night insects are in motion, this species issues forth from its retreat, and begins to give utterance to the peculiar cries from which it receives its trivial name, and which are said to resemble the syllables chuck-wills-wi-dow. These sounds are said to be repeated with great rapidity, yet with clearness and power, six or seven times in as many seconds. They are only uttered for a brief period in the early evening.

Mr. Audubon states that deep ravines, shady swamps, and extensive pine groves, are resorted to by this species for safety during the day, and for food during the night. Their notes are seldom heard in cloudy weather, and never during rain. They roost in hollow trees, standing as well as prostrate, which they never leave by day except during incubation. He adds that whenever he has surprised them in such situations they never attempt to make their escape by flying out, but draw back to the farthest corner, ruffle their feathers, open their mouths to the fullest extent, and utter a hissing sound. When taken to the light, they open and close their eyes in rapid succession, snap their bills in the manner of a Flycatcher, and attempt to shuffle off. When given their liberty, they fly straight forward until quite out of sight, readily passing between the trees in their course.

The flight of this bird is light, like that of the Whippoorwill, and even more elevated and graceful. It is performed by easy flapping of the wings, with occasional sailings and curving sweeps. It sweeps, at night, over the open fields, ascending, descending, or sailing with graceful motions in pursuit of night beetles, moths, and other insects, repeatedly passing and repassing over the same area, and occasionally alighting on the ground to capture its prey. Occasionally it pauses to alight on a stake or a tall plant, and again utters its peculiar refrain, and then resumes its search for insects. And thus it passes pleasant summer nights.

Like all the birds of this family, the Chuck-will’s Widow makes no nest, but deposits her eggs on the ground, often among a collection of dry deciduous leaves, in the forest. These are two in number, and the spot chosen for them are thickets, and the darker and more solitary portions of woods. Dr. Bryant, who took several of their eggs in Florida, informed me that they were in each instance found deposited on beds of dry leaves, but with no attempt at any nest, and always in thick woods.

Sometimes, Mr. Audubon thinks, the parent bird scratches a small space on the ground, among the leaves, before she deposits her eggs. If either their eggs or their young are meddled with, these birds are sure to take the alarm and transport them to some distant part of the forest. In this both parents take part. After this removal Mr. Audubon found it impossible, even with the aid of a dog, to find them again. On one occasion he actually witnessed the act of removal of the eggs, and presumed that they also treat the young in the same manner when they are quite small. The eggs were carried off in the capacious mouths of these birds, each parent taking one and flying off, skimming closely to the ground until lost to sight among the branches and the trees. To what distance they were carried he was unable to ascertain.

During the period of incubation they are silent, and do not repeat their peculiar cries until just before they are preparing to depart on their southern migrations, in August.

The food of these birds consists chiefly, if not altogether, of the larger nocturnal insects, for swallowing which their mouths are admirably adapted, opening with a prodigious expansion, and assisted by numerous long bristles, which prevent the escape of an insect once within their enclosure. In a single instance the remains of a small bird are said to have been found within the stomach of one of this species.

The inner side of each middle claw of the Chuck-will’s Widow is deeply pectinated. The apparent use of this appendage, as in the other species in which it is found, appears to be as an aid in adjusting the plumage, and perhaps to assist in removing vermin.

The eggs of this bird are never more than two in number. They are oval in shape, large for the size of the bird, and alike at either end. Their ground-color is a clear crystal white. They are more or less spotted, and marked over their entire surface with blotches of varying size, of a dark purplish-brown, and cloudings of a grayish-lavender color, with smaller occasional markings of a light raw-umber brown. In shape and markings they very closely resemble those of the Whippoorwill, differing chiefly in their much larger size. They measure 1.44 inches in length by 1.06 in breadth.

Antrostomus vociferus, BonapWHIPPOORWILLCaprimulgus vociferus, Wilson, Am. Orn. V, 1812, 71, pl. xli, f. 1, 2, 3.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 443; V, 405, pl. lxxxv.—Ib. Birds Am. I, 1840, 155, pl. xlii.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 98. Antrostomus vociferus, Bonap. List, 1838.—Cassin, J. A. N. Sc. II, 1852, 122.—Ib. Ill. I, 1855, 236.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 148.—Samuels, 119.—Allen, B. Fla. 300. Caprimulgus virginianus, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, 1807, 55, pl. xxv. “Caprimulgus clamator, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict. X, 1817, 234” (Cassin). Caprimulgus vociferans, Warthausen, Cab. J. 1868, 369 (nesting).

Sp. Char. Bristles without lateral filaments. Wing about 6.50 inches long. Top of the head ashy-brown, longitudinally streaked with black. Terminal half of the tail-feathers (except the four central) dirty white on both outer and inner webs. Length, 10.00; wing, 6.50. Female without white on the tail.

Hab. Eastern United States to the Plains; south to Guatemala (Tehuantepec, Orizaba, Guatemala). Coban (Salv. Ibis, II, 275).

In this species the bristles at the base of the bill, though stiff and long, are without the lateral filaments of the Chuck-will’s Widow. The wings are rather short; the second quill longest; the first intermediate between the third and fourth. The tail is rounded; the outer feathers about half an inch shorter than the middle ones.

The colors of this species are very difficult to describe, although there is quite a similarity to those of A. carolinensis, from which its greatly inferior size will at once distinguish it. The top of the head is an ashy gray, finely mottled, with a broad median stripe of black; all the feathers with a narrow stripe of the same along their centres. The back and rump are somewhat similar, though of a different shade. There is a collar of white on the under side of the neck, posterior to which the upper part of the breast is finely mottled, somewhat as on the top of the head. The belly is dirty white, with indistinct transverse bands and mottlings of brown. The wings are brown; each quill with a series of round rufous spots on both webs, quite conspicuous on the outer side of the primaries when the wings are folded. The terminal half of the outer three tail-feathers is of a dirty white.

The female is smaller; the collar on the throat is tinged with fulvous. The conspicuous white patch of the tail is wanting, the tips only of the outer three feathers being of a pale brownish-fulvous.

Mexican and Guatemalan specimens are identical with those from the United States.

Habits. The well-known Whippoorwill has an extended range throughout the eastern portion of North America, from the Atlantic to the valley of the Missouri, and from Southern Florida to about the 50th parallel of north latitude. Dr. Richardson observed this bird on the northern shores of Lake Huron, but did not meet with it at any point farther north. It is found throughout New England and in portions of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, but is rare in the latter places, and is not common in the vicinity of Calais. It breeds from Florida northward. It has not been found as far west as Texas. It was noticed by Mr. Say at Pembina. It is given by Dr. Hall, of Montreal, as common in that neighborhood, and by Mr. McIlwraith as an abundant summer resident around Hamilton, Canada. Dr. Lembeye names it as a resident Cuban species, and Dr. Gundlach informed me that he had taken its eggs within that island. I have also received its eggs from various portions of Florida.

The Whippoorwill is nowhere a resident species in any portion of the United States. They make their appearance in the Southern States early in March, and very gradually proceed northward, entering Pennsylvania early in April, but not being seen in New York or New England until the last of that month, and sometimes not until the 10th of May. Mr. Maynard mentions their first appearance in Massachusetts as from the 19th to the 24th of May, but I have repeatedly known them in full cry near Boston at least a fortnight earlier than this, and in the western part of the State Mr. Allen has noted their arrival by the 25th of April. They leave in the latter part of September. Mr. Allen also observed the abundant presence of these birds in Western Iowa, where he heard their notes as late as the 20th of September.

In its habits the Whippoorwill is very nearly the counterpart of the carolinensis. Like that bird, it is exclusively nocturnal, keeping, during the day, closely within the recesses of dark woods, and remaining perfectly silent, uttering no note even when disturbed in these retreats. In very cloudy weather, late in the day, these birds may be seen hunting for insects, but this is not usual, and they utter no sound until it is quite dark.

Like the preceding species, this bird receives its common name of Whippoorwill from its nocturnal cry, which has some slight resemblance to these three sounds; but the cry is so rapidly enunciated and so incessantly repeated that a fertile imagination may give various interpretations to the sounds. They are never uttered when the bird is in motion, but usually at short intervals, when resting on a fence, or bush, or any other object near the ground.

Their flight is noiseless to an incredible degree, and they rarely fly far at a time. They are usually very shy, and are easily startled if approached. At night, as soon as the twilight disappears, these birds issue from their retreats, and fly out into more open spaces in quest of their favorite food. As many of the nocturnal insects, moths, beetles, and others, are attracted about dwellings by lights, the Whippoorwill is frequently enticed, in pursuit, into the same vicinity. For several successive seasons these birds have appeared nearly every summer evening within my grounds, often within a few feet of the house. They never suffer a very near approach, but fly as soon as they notice any movement. Their pursuit of insects is somewhat different from that narrated of the preceding species, their flights being usually quite brief, without any perceptible sailing, and more in the manner of Flycatchers. Their song is given out at intervals throughout the night, until near the dawn.