полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

The nocturnal habits of this bird have prevented a general or accurate knowledge of its true character. Strange as it may seem, in many parts of the country the Night-Hawk and the Whippoorwill are supposed to be one and the same bird, even by those not ill informed in other respects. This was found to be the case in Pennsylvania by Wilson, and is equally true of many portions of New England, though disputed by Mr. Audubon.

Like the Chuck-will’s Widow, this species removes its eggs, and also its young, to a distant and safer locality, if they are visited and handled. Wilson once, in passing through a piece of wood, came accidentally upon a young bird of this species. The parent attempted to draw him away by well-feigned stratagems. Wilson stopped and sketched the bird, and, returning again, after a short absence, to the same place, in search of a pencil he had left behind, found that the bird had been spirited away by its vigilant parent.

When disturbed by an intrusive approach, the Whippoorwill resorts to various expedients to divert attention to herself from her offspring. She flutters about as if wounded and unable to fly, beats the ground with her wings as if not able to rise from it, and enacts these feints in a manner to deceive even the most wary, risking her own life to save her offspring.

The Whippoorwills construct no nest, but deposit their eggs in the thickest and most shady portions of the woods, among fallen leaves, in hollows slightly excavated for that purpose, or upon the leaves themselves. For this purpose elevated and dry places are always selected, often near some fallen log. There they deposit two eggs, elliptical in shape. Their young, when first hatched, are perfectly helpless, and their safety largely depends upon their great similarity to small pieces of mouldy earth. They grow rapidly, and are soon able to follow their mother and to partially care for themselves.

The egg of the Whippoorwill has a strong family resemblance to those of both species of European Caprimulgi, and is a complete miniature of that of A. carolinensis. In shape it is oblong and oval, equally obtuse at either end. Resembling the egg of the Chuck-will’s Widow, it is yet more noticeable for the purity of its colors and the beauty of their contrast. The ground-color is a clear and pure shade of cream-white. The whole egg is irregularly spotted and marbled with lines and patches of purplish-lavender, mingled with reddish-brown. The former are fainter, and as if partially obscured, the brown usually much more distinct. The eggs measure 1.25 inches in length by .88 of an inch in breadth. Wilson’s account of its egg is wholly inaccurate.

In the extreme Southern States these eggs are deposited in April, in Virginia and Pennsylvania about the middle of May, and farther north not until early in June. The young are hatched and able to care for themselves during July, but, with the female, rarely leave the woods. The notes of the male are once more occasionally heard in August. Mr. Allen has heard them late in September, but I have never happened to notice their cries later than August.

Mr. Nuttall states that the young of these birds, at an early age, run about with remarkable celerity, and that they utter, at short intervals a pé-ūgh, in a low mournful tone. Their food appears to consist of various kinds of nocturnal insects, besides ants, grasshoppers, and other kinds not nocturnal, frequenting decaying wood and shady thickets.

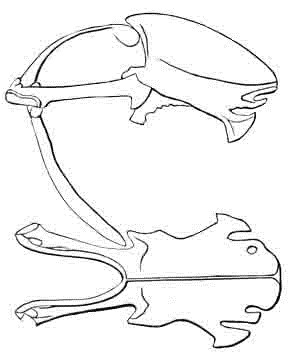

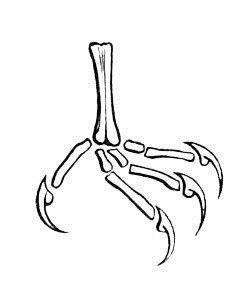

Left foot of Antrostomus vociferus.

Left foot of Nyctibius jamaicensis.

Antrostomus nuttalli, CassinNUTTALL’S WHIPPOORWILL; POOR-WILL

Caprimulgus nuttalli, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, pl. ccccxcv, Appendix. Antrostomus nuttalli, Cassin, J. A. N. Sc. Phila. 2d series, II, 1852, 123.—Ib. Ill. I, 1855, 237.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Oregon Route, 77; Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VI, IV.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 149.—Cooper & Suckley, 166.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. I, 1870, 341.

Sp. Char. Rictal bristles without any lateral filaments; wing, about 5.50; the top of the head hoary gray, with narrow and transverse, not longitudinal bands. Tail above, except the central feathers, nearly black on the terminal half, the extreme tip only (in the outer feather of each side) being white for nearly an inch, diminishing on the second and third. Length, 8.00; wing, 5.50. Female without the white tip of tail. Audubon describes the male as follows: “Bill, black; iris, dark hazel; feet, reddish-purple; scales and claws, darker; general color of upper parts dark brownish-gray, lighter on the head and medial tail-feathers, which extend half an inch beyond the others, all which are minutely streaked and sprinkled with brownish-black and ash-gray. Quills and coverts dull cinnamon color, spotted in bars with brownish-black; tips of former mottled with light and dark brown; three lateral tail-feathers barred with dark brown and cinnamon, and tipped with white. Throat brown, annulated with black; a band of white across foreneck; beneath the latter black, mixed with bars of light yellowish-gray and black lines. Under tail-coverts dull yellow. Length, 7.25; wing, 5.75; bill, edge, .19; second and third quills nearly equal. Tail to end of upper feathers, 3.50; tarsus, .63; middle toe, .63; claw, .25; strongly pectinated.”

Hab. High Central Plains to the Pacific coast. San Antonio, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 471, breeds); W. Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 58); Guanajuata, Mex. (Salvin, p. 1014).

Nuttall’s Whippoorwill is readily distinguished from the other North American species by the transverse, not longitudinal, lines on the top of head, the narrow white tip of tail on both webs, and the inferior size, as well as by numerous other points of difference.

Habits. This species was first described by Mr. Audubon from a specimen obtained near the Rocky Mountains, but with no information in regard to any peculiarities of habit. From Mr. Nuttall we learn that these birds were first observed by him on the 10th of June, amidst the naked granite hills of the sources of the Upper Platte River, called Sweet-Water. It was about twilight, and from the clefts of the rocks they were uttering at intervals a low wailing cry, in the manner of the Whippoorwill, and sounding like the cry of the young of that species, or pē-cū. Afterwards, on the 7th of August, when encamped on the high ravine of the insulated mountains so conspicuous from Lewis River, called the Three Buttes, this bird was again observed, as it flew from under a stone near the summit of the mountain. It flew about hawking for insects near their elevated camp, for two or three hours, but was now silent. On the 16th of June, near the banks of the Sandy River of the Colorado, Mr. Nuttall again heard its nocturnal cry, which he says sounded like pēvai.

Dr. Cooper did not meet with this bird in the Colorado Valley, but he heard their nocturnal call, which he says sounds like poor-will, on the barren mountains west of the valley, in May. He has never seen or heard any west of the Coast Range, nor in the Santa Clara Valley in the spring. They are, however, said to be common in the hot interior valleys, and remain near San Francisco as late as November, usually hiding on the ground, and flying at dusk in short, fitful courses in pursuit of insects. Dr. Cooper adds that they inhabit the almost bare and barren sage-plains east of the Sierra Nevada, where their rather sad whistle is heard all night during the spring, sounding like an echoing answer to the cry of the eastern species.

Dr. Suckley, in the Report on the Zoölogy of Washington Territory, speaks of this species as moderately abundant in the interior of that Territory, as well as of Oregon. East of the Cascade Mountains, at Fort Dalles, they can be heard on almost any fine night in spring or early summer. Their cries closely resemble those of the vociferus, but are more feeble, and not so incessantly kept up. Dr. Cooper, in the same report, also speaks of finding this bird common near the Yakima River, in 1853. Two specimens were killed in the daytime by a whip. Late in the evening he found them flying near the ground. Dr. Woodhouse, in passing down the Little Colorado River, in New Mexico, found this bird quite abundant, as also among the San Francisco Mountains.

Dr. Newberry met with this species in all the parts of California and Oregon visited by him. Near the shores of Rhett Lake he met with its nest containing two young nearly ready to fly. The old bird fluttered off as if disabled, and by her cries and strange movements induced one of the party to pursue her. The young resembled those of the eastern species, were of a gray-brown color, marbled with black, and had large, dark, and soft eyes. They were quite passive when caught.

This species was observed by Mr. J. H. Clark near Rio Mimbres, in New Mexico. From the manner in which it flew, it seemed so similar to the Woodcock that until a specimen was obtained it was supposed to belong to that family. He saw none east of the Rio Grande, but met with it as far west as Santa Cruz. It was nowhere abundant, and was generally solitary. It was found usually among the tall grass of the valleys, and occasionally on the plains. It was only once observed to alight upon a bush, but almost invariably, when started up, it flew down again among the grass at a short distance.

A single specimen of this bird was taken by Dr. Kennerly on the Great Colorado River. Dr. Heermann met with two specimens among the mountains bordering the Tejon Valley, and he was informed by Dr. Milhau that a small species of Whippoorwill was abundant round that fort in the spring and summer.

Dr. Heermann killed one of these birds on the Medina, in Texas; and during the summer, passing along Devil’s River, he heard their notes every evening, and judged that the birds were abundant. Mr. Dresser obtained a single specimen, shot near the town of San Antonio, where it was of uncommon occurrence. He received also another specimen from Fort Stockton. During his stay at Matamoras he did not notice this bird, but was informed that a kind resembling this species was very common at a rancho about twenty-five miles distant, on the Monterey road. Dr. Coues found this species particularly abundant throughout Arizona. At Fort Whipple it was a summer resident, arriving there late in April and remaining until October. So numerous was it in some localities, that around the campfires of the traveller a perfect chorus of their plaintive two-syllabled notes was continued incessantly through the night, some of the performers being so near that the sharp click of their mandibles was distinctly audible.

Mr. J. A. Allen found this species abundant on the lower parts of the mountains in Colorado, and heard the notes of scores of them near the mouth of Ogden Cañon on several occasions after nightfall. Though so numerous, all efforts to procure specimens were futile, as it did not usually manifest its presence till after it became too dark for it to be clearly distinguished. He saw it last, October 7, during a severe snow-storm on the mountains north of Ogden. It had been quite common during the greater part of September. He also met with this bird at an elevation of 7,000 feet. He had previously ascertained its presence throughout Kansas from Leavenworth to Fort Hays.

From these varied observations the range of this species may be given as from the valley of the Rio Grande and the more northern States of Mexico, throughout New Mexico, Arizona, and the Great Plains nearly to the Pacific, in California, Oregon, and Washington Territory.

The egg of this species (13,587) was obtained among the East Humboldt Mountains, by Mr. Robert Ridgway, July 20, 1868. Its measurement is 1.06 inches in length by .81 of an inch in breadth. It is of a regularly elliptical form, being equally rounded at either end. Its color is a clear dead-white, entirely unspotted. The egg was found deposited on the bare ground beneath a sage-bush, on a foot-slope of the mountains. The nest was nothing more than a bare spot, apparently worn by the body of the bird. When found, the male bird was sitting on the egg, and was shot as it flew from the spot.

Mr. Salvin (Ibis, III, p. 64) mentions taking, April 20, 1860, on the mountains of Santa Barbara, Central America, a species of Antrostomus, a female, with two eggs. This is spoken of as nearly allied to, perhaps identical with, A. vociferus. Its eggs are, however, spoken of as white, measuring 1.05 inches by .80 of an inch, almost exactly the size of the eggs of this species. Mr. Salvin adds: “I do not quite understand these eggs being white, except by supposing them to be accidentally so. In other respects, i. e. in form and texture, they agree with the eggs of other species of Caprimulgidæ. These eggs, two in number, were on the ground at the foot of a large pine-tree. There was no nest.”

In regard to the parentage of the eggs thus discovered, the coloration and size of which correspond so closely with those of the Poor-will, Mr. Salvin writes, in a letter dated March 10, 1872: “In respect to the Antrostomus which lays white eggs in Guatemala, I have carefully examined the skin of the female sent to me with the eggs in question, and represented as their parent. It certainly is not A. nuttalli, but appears to belong to the species described by Wagler as A. macromystax. This species is very closely allied to A. vociferus, but appears to be sufficiently distinct, inasmuch as the rictal bristles are very long, the throat is almost without white feathers, and the white on the tail is more limited in extent than in A. vociferus. The true A. vociferus is frequently found in winter in Guatemala, but is probably only a migrant. The other species would certainly appear to be a resident in South Mexico and Guatemala. With respect to A. nuttalli, I may add that I have recently acquired a skin from Guanajuata, in Mexico. This is the first instance of the occurrence of the species in Mexico at all, that I am aware of.”

Mr. Ridgway met with the Poor-will from the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada to the Wahsatch and Uintah Mountains. He describes its notes as much like those of the eastern A. vociferus, except that the first syllable is left off, the call sounding like simply poor-will, the accent on the last syllable. It frequents chiefly the dry mesa and foot-hills of the mountains, and lives almost entirely on the ground, where its two white unspotted eggs are deposited beneath some small scraggy sage-bush, without any sign of a nest whatever. Both sexes incubate.

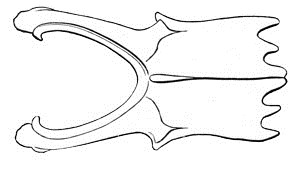

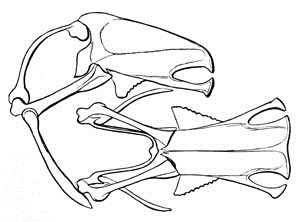

Sternum of Chordeiles virginianus.

Sternum of Nyctibius jamaicensis.

Sternum of Caprimulgus stictomus.

Family CYPSELIDÆ.—The Swifts

Char. Bill very small, without notch, triangular, much broader than high; the culmen not one sixth the gape. Anterior toes cleft to the base, each with three joints, (in the typical species,) and covered with skin or feathers; the middle claw without any serrations; the lateral toes nearly equal to the middle. Bill without bristles, but with minute feathers extending along the under margin of the nostrils. Tail-feathers ten. Nostrils elongated, superior, and very close together. Plumage compact. Primaries ten, elongated, falcate.

The Cypselidæ, or Swifts, are Swallow-like birds, generally of rather dull plumage and medium size. They were formerly associated with the true Swallows on account of their small, deeply cleft bill, wide gape, short feet, and long wings, but are very different in all the essentials of structure, belonging, indeed, to a different order or suborder. The bill is much smaller and shorter; the edges greatly inflected; the nostrils superior, instead of lateral, and without bristles. The wing is more falcate, with ten primaries instead of nine. The tail has ten feathers instead of twelve. The feet are weaker, without distinct scutellæ; the hind toe is more or less versatile, the anterior toes frequently lack the normal number of joints, and there are other features which clearly justify the wide separation here given, especially the difference in the vocal organs. Strange as the statement may be, their nearest relatives are the Trochilidæ, or Humming-Birds, notwithstanding the bills of the two are as opposite in shape as can readily be conceived. The sternum of the Cypselidæ is also very different from that of the Hirundinidæ, as will be shown by the accompanying figure. There are no emarginations or openings in the posterior edge, which is regularly curved. The keel rises high, for the attachment of the powerful pectoral muscles. The manubrium is almost entirely wanting.

Chætura pelagica.

Progne subis.

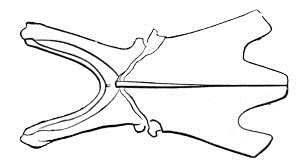

In this family, as in the Caprimulgidæ, we find deviations in certain forms from the normal number of phalanges to the toes, which serve to divide it into two sections. In one, the Chæturinæ, these are 2, 3, 4, and 5, as usual; but in the Cypselinæ they are 2, 3, 3, and 3, as shown in the accompanying cut borrowed from Dr. Sclater’s masterly memoir on the Cypselidæ, (Pr. Zoöl. Soc. London, 1865, 593), which also serves as the basis of the arrangement here presented.

Left foot of Chætura zonaris.

Left foot of Panyptila melanoleuca.

Cypselinæ. Tarsi feathered; phalanges of the middle and outer toes three each (instead of four and five). Hind toe directed either forward or to one side, not backward.

Tarsi feathered; toes bare; hind toe directed forward … Cypselus.

Both tarsi and toes feathered; hind toe lateral … Panyptila.

Chæturinæ. Tarsi bare; phalanges of toes normal (four in middle toe, five in outer). Hind toe directed backwards, though sometimes versatile.

Tarsi longer than middle toe.

Tail-feathers spinous.

Shafts of tail-feathers projecting beyond the plumage … Chætura.

Shafts not projecting, (Nephæcetes) … Cypseloides.

Tail-feathers not spinous … Collocallia.

Tarsi shorter than middle toe … Dendrochelidon.

The Swifts are cosmopolite, occurring throughout the globe. All the genera enumerated above are well represented in the New World, except the last two, which are exclusively East Indian and Polynesian. Species of Collocallia make the “edible bird’s-nests” which are so much sought after in China and Japan. These are constructed entirely out of the hardened saliva of the bird, although formerly supposed to be made of some kind of sea-weed. All the Cypselidæ have the salivary glands highly developed, and use the secretion to cement together the twigs or other substances of which the nest is constructed, as well as to attach this to its support. The eggs are always white.

There are many interesting peculiarities connected with the modification of the Cypselidæ, some of which may be briefly adverted to. Those of our common Chimney Swallow will be referred to in the proper place. Panyptila sancti-hieronymæ of Guatemala attaches a tube some feet in length to the under side of an overhanging rock, constructed of the pappus or seed-down of plants, caught flying in the air. Entrance to this is from below, and the eggs are laid on a kind of shelf near the top. Chætura poliura of Brazil again makes a very similar tube-nest (more contracted below) out of the seeds of Trixis divaricata, suspends it to a horizontal branch, and covers the outside with feathers of various colors. As there is no shelf to receive the eggs, it is believed that these are cemented against the sides of the tube, and brooded on by the bird while in an upright position. Dendrochelidon klecho, of Java, etc., builds a narrow flat platform on a horizontal branch, of feathers, moss, etc., cemented together, and lays in it a single egg. The nest is so small that the bird sits on the branch and covers the egg with the end of her belly.

Owing to the almost incredible rapidity in flight of the Swifts, and the great height in the air at which they usually keep themselves, the North American species are, of all our land birds, the most difficult to procure, only flying sufficiently near the surface of the ground to be reached by a gun in damp weather, and then requiring great skill to shoot them. Their nests, too, are generally situated in inaccessible places, usually high perpendicular or overhanging mountain-cliffs. Although our four species are sufficiently abundant, and are frequently seen in flocks of thousands, it is only the common Chimney Swift that is to be met with at all regularly in museums.

Subfamily CYPSELINÆ

The essential character of this subfamily, as stated already, is to be found in the feathered tarsus; the reduction of the normal number of phalanges in the middle toe from 4 to 3, and of the outer toe from 5 to 3, as well as in the anterior or lateral position of the hind toe, not posterior. Of the two genera assigned to it by Dr. Sclater, one, Cypselus, is enlarged by him so as to include the small West Indian Palm Swifts, Tachornis of Gosse.

Genus PANYPTILA, CabanisPanyptila, Cabanis, Wiegm. Archiv, 1847, I, 345.—Burmeister, Thiere Bras. Vögel, I, 1856, 368. (Type, Hirundo cayanensis, Gm.)

Pseudoprocne, Streubel, Isis, 1848, 357. (Same type.)

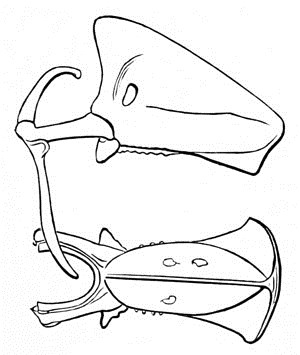

Panyptila melanoleuca.

6018 ♂

Gen. Char. Tail half as long as the wings, moderately forked; the feathers rather lanceolate, rounded at tip, the shafts stiffened, but not projecting. First primary shorter than the second. Tarsi, toes, and claws very thick and stout; the former shorter than the middle toe and claw, which is rather longer than the lateral one; middle claw longer than its digit. Hind toe very short; half versatile, or inserted on the side of the tarsus. Tarsi and toes feathered to the claws, except on the under surfaces.

Three species of this genus are described by authors, all of them black, with white throat, and a patch of the same on each side of rump, and otherwise varied with this color. The type P. cayanensis is much the smallest (4.70), and has the tail more deeply forked than P. melanoleuca.

Synopsis of SpeciesP. cayanensis. Glossy intense black; a supraloral spot of white; white of throat transversely defined posteriorly. Tail deeply forked, the lateral feathers excessively attenuated and acute.

Wing, 4.80; middle tail-feather, 1.20, external, 2.30. Hab. Cayenne and Brazil … var. cayanensis.108

Wing, 7.30; middle tail-feather, 1.90, external, 3.60. Hab. Guatemala … var. sancti-hieronymi.109

P. melanoleuca. Lustreless dull black; no supraloral white spot, but instead a hoary wash; white of throat extending back along middle of abdomen to the vent. Tail moderately forked, the lateral feathers obtuse. Wing, 5.75; middle tail-feather, 2.30, outer, 2.85. Hab. Middle Province of United States, south to Guatemala.