полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Lieutenant Couch, in a letter to Mr. Cassin, states that he first met with this bird at Charco Escondido, in Tamaulipas, on the 10th of March. The males had come in advance of the females, as the latter were not observed until several weeks afterwards. Early in the morning, and again about sunset, one of these birds came to the artificial lake constructed there for the supply of water to the inhabitants. It appeared to be of a very quiet and inoffensive disposition, usually sitting on the upper branches of the trees, occasionally uttering a low chirp. He subsequently met with these birds in Nueva Leon. In their habits they appeared to be in some respects similar to the smaller northern Flycatchers.

Dr. Henry also met with these birds in the vicinity of Fort Webster, in New Mexico; he found them exceedingly rare, and his observations were confirmatory of their partiality for the neighborhood of water. His first specimen was obtained on the Rio Mimbres, near Fort Webster, in the month of March.

Dr. Woodhouse met with an individual of this Flycatcher near the settlement of Quihi, in Texas, in the month of May. It was breeding in a thicket. He did not hear it utter any note.

According to the observations of Mr. Sumichrast, this bird is very abundant throughout the entire Department of Vera Cruz, common everywhere, at all heights, in the hot, the temperate, and the alpine regions. Mr. Dresser obtained a fine male specimen from the San Pedro River, near San Antonio, in August. Another, a young male, was obtained September 25. It was very shy, and made its way through the low bushes like the Hedge Sparrow of Europe. A third was obtained April 5, after much difficulty. It was not so shy as the others, but kept more in the open country, always perching on some elevated place. Its note resembled that of the Milvulus forficatus.

This bird, according to Dr. Coues, is not found as far to the north as Fort Whipple, among the mountains, though it extends up the valley of the Colorado to an equally high latitude. It is also said to be common in the valley of the Gila and in Southern Arizona generally.

Mr. E. C. Taylor (Ibis, VI, p. 86) mentions finding this Flycatcher tolerably abundant both at Ciudad Bolivar and at Barcelona, but he did not meet with a specimen on the island of Trinidad. He notes its great resemblance in habits to the Muscicapæ of Europe.

Dr. Kennerly reports that these birds were often observed by him at various points on the road, from Boca Grande to Los Nogales. It generally selected its perch on the topmost branch of some bush or tree, awaiting the approach of its insect food, and then sallying out to capture it. Sometimes it poised itself in a graceful manner in the air, while its bright plumage glistened in the sun like some brightly colored flower.

Dr. Heermann procured a specimen of this Flycatcher at Fort Yuma, where he was informed that it was quite common in spring. He saw other individuals of this species at Tucson in Sonora. These birds, he states, station themselves upon the topmost branches of trees, and when pursued appear quite wild, flying to a considerable distance before again alighting.

Dr. Cooper saw at Fort Mohave, May 24, a bird which he had no doubt was an individual of this species, but he was not able to procure it. It perched upon the tops of bushes, and would not suffer him to approach within shooting distance. One has since been taken by Mr. W. W. Holden in Colorado Valley, lat. 34°, April 18.

Mr. Joseph Leyland found this species common on the flats near Peten, in Guatemala, as also on the pine ridges of Belize. They have, he states, a singular habit of spinning round and round on the wing, and then dropping suddenly with wings loose and fluttering as though shot,—apparently done for amusement. They lay three or four light-colored eggs in a small nest composed of light grass and lined with cottony materials. Mr. Xantus found the nest and eggs of this species at San José, Mexico, May 16, 1861.

Family ALCEDINIDÆ.—The Kingfishers

Char. Head large; bill long, strong, straight, and sub-pyramidal, usually longer than the head. Tongue very small. Wings short; legs small; the outer and middle toes united to their middle. Toes with the usual number of joints (2, 3, 4, 5).

The gape of the bill in the Kingfishers is large, reaching to beneath the eyes. The third primary is generally longest; the first decidedly shorter; the secondaries vary from twelve to fifteen in number, all nearly equal. The secondaries cover at least three quarters of the wing. The tail is short, the feathers twelve in number; they are rather narrow, the outer usually shorter. The lower part of the tibia is bare, leaving the joint and the tarsus uncovered. The tarsus is covered anteriorly with plates; behind, it is shagreen-like or granulated. The hind toe is connected with the inner, so as to form with it and the others a regular sole, which extends unbroken beneath the middle and outer as far as the latter are united. The inner toe is much shorter than the outer. The claws are sharp; the middle expanded on its inner edge, but not pectinated.

The North American species of Kingfisher belong to the subfamily Cerylinæ, characterized by the crested head, and the plumage varying with sex and age. The single genus Ceryle includes two types, Streptoceryle and Chloroceryle.

Genus CERYLE, BoieCeryle, Boie, Isis, 1828, 316, ch. (Type, Alcedo rudis of Africa.)

Ispida, Sw. Birds, II, 1837, 336. (Type, A. alcyon, in part.)

Gen. Char. Bill long, straight, and strong, the culmen slightly advancing on the forehead and sloping to the acute tip; the sides much compressed; the lateral margins rather dilated at the base, and straight to the tip; the gonys long and ascending. Tail rather long and broad. Tarsi short and stout.

This genus is distinguished from typical Alcedo (confined to the Old World) by the longer tail, an indented groove on each side the culmen, inner toe much longer than the hinder instead of equal, etc.

The two species of North American Kingfishers belong to two different subgenera of modern systematists, the one to Streptoceryle, Bonap., the other to Chloroceryle, Kaup. The characters of these subgenera are as follows:—

Streptoceryle, Bonap. (1854). Bill very stout and thick. Tarsus about equal to the hind toe; much shorter than the inner anterior. Plumage without metallic gloss; the occipital feathers much elongated, linear, and distinct. Type, C. alcyon.

Chloroceryle, Kaup (1849). Size smaller and shape more slender than in the preceding. Bill long, thin. Tarsi longer than hind toe; almost or quite as long as the inner anterior. Plumage with a green metallic gloss above; the occiput with a crest of rather short, indistinct feathers. Type, A. amazona.

Ceryle alcyon.

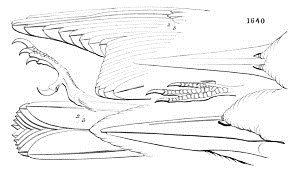

1640

The genus Ceryle was established by Boie on the Alcedo rudis, of Linnæus, an African species. Modern systematists separate the American Kingfishers from those of the Old World, and if correct in so doing, another generic name must be selected for the former. If the two American sections be combined into one, Chloroceryle of Kaup (type, Alcedo amazona) must be taken as being the older, unless, indeed, Ispida of Swainson (1837) be admissible. This appears to have been based on Alcedo alcyon, although including also some Old World species.

Ceryle alcyon, BoieBELTED KINGFISHERAlcedo alcyon, Linnæus, Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 180.—Wilson, Am. Orn. III, 1811, 59.—Audubon, Orn. Biog. I, 1831, 384, pl. lxxvii.—Ib. Birds America.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858, 102. Ceryle alcyon, Boie, Isis, 1828, 316.—Brewer, N. Am. Oology, I, 1857, 110, pl. iv, fig. 52 (egg).—Wood, Am. Naturalist, 1868, 379 (nesting).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 158.—Cooper & Suckley, 167.—Dall & Bannister, Ch. Ac. I, i, 1869, 275 (Alaska).—Finsch, Abh. Nat. III, 1872, 29 (Alaska).—Samuels, 125.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 337.—Allen, B. Fla. 300. Megaceryle alcyon, Reichenb. Handb. Sp. Orn. I, II, 1851, 25, pl. ccccxii, fig. 3108-9. Ispida ludoviciana, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 452. “Alcedo jaguacate, Dumont, Dict. Sc. Nat. I, 1816, 455” (Cassin). “Alcedo guacu, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict. XIX, 1818, 406,” (Cassin). Streptoceryle alcyon, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. II, 151.

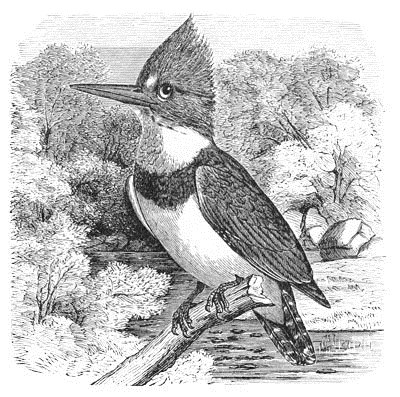

Sp. Char. Head with a long crest. Above ashy-blue, without metallic lustre. Beneath, with a concealed band across the occiput, and a spot anterior to the eye, pure white. A band across the breast, and the sides of the body under the wings, like the back.

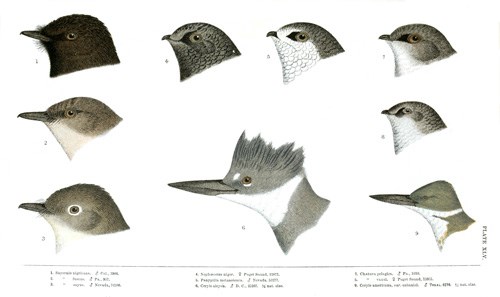

PLATE XLV.

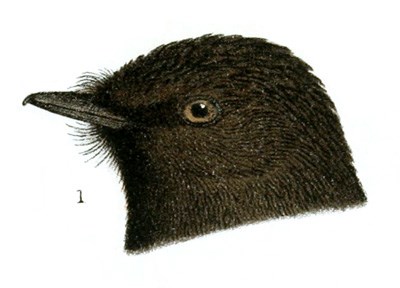

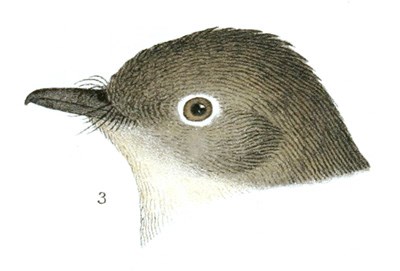

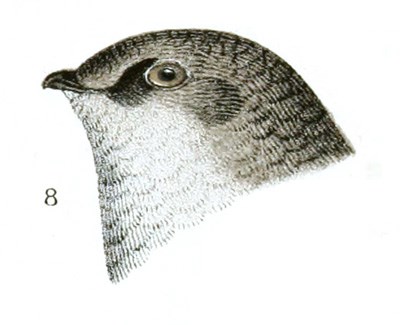

1. Sayornis nigricans. ♂ Cal., 3906.

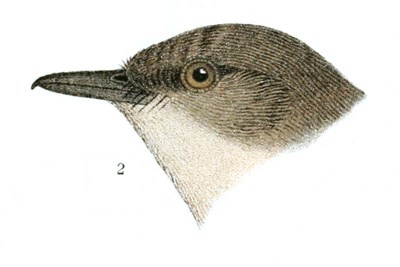

2. Sayornis fuscus. ♂ Pa., 957.

3. Sayornis sayus. ♂ Nevada, 52286.

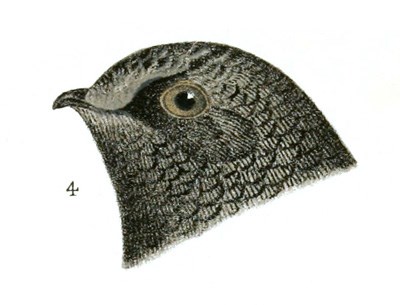

4. Nephœcetes niger. ♀ Puget Sound, 11871.

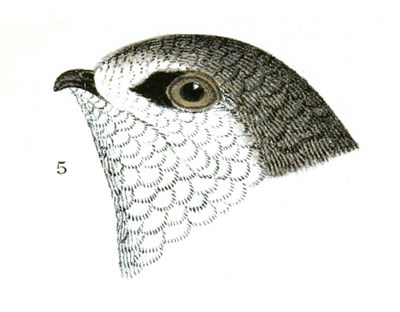

5. Panyptila melanoleuca. ♂ Nevada, 53277.

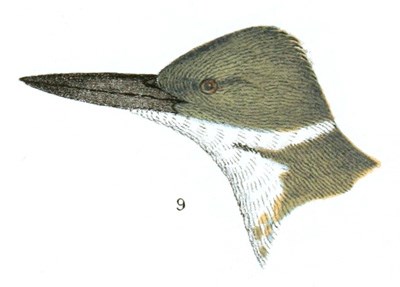

6. Ceryle alcyon. ♂ D. C., 25207. ½ nat. size.

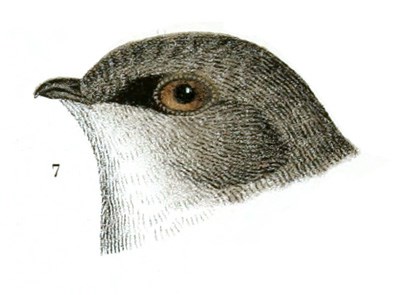

7. Chætura pelagica. ♂ Pa., 1010.

8. Chætura vauxi. ♀ Puget Sound, 15955.

9. Ceryle americana, var. cabanisi. ♂ Texas, 6194. ½ nat. size.

Primaries white on the basal half, the terminal unspotted. Tail with transverse bands and spots of white. Female and young with sides of body and a band across the belly below the pectoral one light chestnut; the pectoral band more or less tinged with the same. Length of adult about 12.75 inches; wing, 6.00.

Ceryle alcyon.

Hab. The entire continent of North America to Panama, including West Indies. Localities: Honduras (Moore, P. Z. S. 1859, 53; Scl. Ibis, II, 116); Sta. Cruz, winter (Newton, Ibis, I, 67); Belize (Scl. Ibis, I, 131); York Factory, H. B. T. (Murray, Edinb. Phil. J. Jan. 1860); Cuba (Cab. J. IV, 101; Gundl. Rep. I, 1866, 292); Bahamas (Bryant, Bost. Soc. VII, 1859); Jamaica (Gosse, Birds Jam. 81); Orizaba (Scl. P. Z. S. 1860, 253); Panama (Lawr. N. Y. Lyc. 1861, 318 n.); Costa Rica (Cab. J. 1862, 162; Lawr. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 118); Tobago (Jard. Ann. Mag. 19, 80); Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 471); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 59); Sta. Bartholemy (Sund. Ofv. 1869, 585).

This species varies considerably in size with locality, as do so many others. Western specimens are appreciably larger, especially those from the northwest coast. According to Nuttall and Audubon, it is the female that has the transverse band of chestnut across the belly. In this they may be correct; but several specimens in the Smithsonian collection marked female (perhaps erroneously) show no indication of the chestnut.101

Two closely allied but much larger species belong to Middle and South America. They differ in having the whole body beneath of a reddish color.

Habits. The common Belted Kingfisher of North America is a widely distributed species at all times, and in the summer is found in every portion of North America, to the Arctic Ocean on the north, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It is more or less resident throughout the year, and in mild and open winters a few have been known to linger throughout New England, and even in higher latitudes. In 1857 Captain Blakiston found it remaining on the lower part of the Saskatchewan River until the 7th of October; and afterwards, in 1859, at Pembina, on the 1st of May, he observed them to be present, although the river was not yet open. Those that have migrated to the south make their reappearance in spring throughout the continent as soon as, and not unfrequently before, the ice has disappeared from the rivers and ponds.

It occurs in extreme northern latitudes. Mr. MacFarlane received skins from the Eskimos obtained on the Arctic coast, and Mr. Dall found them breeding at Fort Yukon, where it was quite common on all the small streams flowing into that river. It was also found by Dr. Richardson frequenting all the large streams of the fur countries, as far at least as the 67th parallel. In California a larger race than our Atlantic species is found abundantly along the coast, and about nearly every stream or lake in which the water is not turbid and muddy.

Mr. A. Newton reports this bird as a winter visitant at St. Croix, leaving the island late in April. It frequents mangrove swamps and the mouths of small streams, sometimes fishing half a mile out at sea. The stomach of one contained shells of crabs. The occurrence of two specimens of this species in Ireland is recorded by Mr. Thompson.

The Kingfisher is an eminently unsocial species. It is never found other than in solitary pairs, and these are very rarely seen together. They feed almost entirely upon fish, which they capture by plunging into the water, and which they always swallow whole on emerging from their bath. Undigested portions of their food, such as scales, bones, etc., they have the power of occasionally ejecting from their stomachs. They may usually be noticed by the side of streams, mill-ponds, and lakes, stationed on some convenient position that enables them to overlook a deep place suitable for their purpose, and they rarely make a plunge without accomplishing their object.

The cry of the Kingfisher, uttered when he is disturbed, or when moving from place to place, and occasionally just as he is about to make a plunge, is loud and harsh, and resembles the noise made by a watchman’s rattle. This noise he makes repeatedly at all hours, and most especially at night, during the breeding-season, whenever he returns to the nest with food for his mate or young.

They nest in deep holes excavated by themselves in the sides of streams, ponds, or cliffs, not always in the immediate vicinity of water. These excavations are often near their accustomed fishing-grounds, in some neighboring bank, usually not many feet from the ground, always in dry gravel, and sufficiently high to be in no danger of inundation. They make their burrow with great industry and rapidity, relieving one another from time to time, and working incessantly until the result is satisfactorily accomplished. When digging through a soft fine sand-bank their progress is surprising, sometimes making a deep excavation in a single night. The pages of “The American Naturalist” contain several animated controversies as to the depth, the shape, and the equipments of these passages. The result of the evidence thus given seems to be that the holes the Kingfishers make are not less than four nor more than fifteen feet in length; that some are perfectly straight, while some, just before their termination, turn to the right, and others to the left; and that all have, at or near the terminus, an enlarged space in which the eggs are deposited. Here the eggs are usually laid on the bare sand, there being very rarely, if ever, any attempt to construct a nest. The use of hay, dry grass, and feathers, spoken of by the older writers, does not appear to be confirmed by more recent testimony. Yet it is quite possible that in certain situations the use of dry materials may be resorted to to protect the eggs from a too damp soil.

The place chosen for the excavation is not always near water. In the spring of 1855 I found the nest of a Kingfisher in a bank by the side of the carriage path on Mount Washington, more than a mile from any water. It was a shallow excavation, made that season, and contained fresh eggs the latter part of May. The food of the pair was taken near the dam of a sawmill on Peabody River. In another instance a pair of Kingfishers made their abode in a sand-bank in the midst of the village of Hingham, within two rods of the main street, and within a few feet of a dwelling, and not in the near vicinity of water. Here the confidence they displayed was not misplaced. They were protected, and their singular habits carefully and curiously watched. During the day they were cautious, reticent, and rarely seen, but during the night they seemed to be passing back and forth continually, the return of each parent being announced by a loud rattling cry. Later in the season, when the young required constant attention, these nocturnal noises seemed nearly incessant, and became almost a nuisance to the family.

The Kingfisher, having once selected a situation for its nest, is very tenacious of it, and rarely forsakes it unless compelled to by too great annoyances. They will submit to be robbed time after time, and still return to the same spot and renew their attempts. They are devoted to their young, exhibit great solicitude if their safety is threatened, and will suffer themselves to be taken from their nest rather than leave it, and immediately return to it again.

Mr. Dall observed a male bird of this species digging other holes in the bank near his nest, apparently for amusement or occupation. They were never more than two feet in length and about eight inches in diameter. He seemed to abandon them as soon as made, though seen to retire into one to eat a fish he had captured.

The eggs are usually six, rarely seven, in number, and are of a beautifully clear crystal whiteness. They are very nearly spherical in shape, and measure 1.31 by 1.06 inches.

Ceryle americana, var. cabanisi, TschudiTEXAS KINGFISHER; GREEN KINGFISHERAlcedo americana, Gmelin, Syst. Nat. I, 1788, 451 (in part). Ceryle americana, Lawrence, Annals N. Y. Lyceum, V, 1851, 118 (first introduction into the fauna of United States).—Cassin, Illustrations, I, 1855, 255.—Brewer, N. Am. Oology, I, 1857, 3, pl. iv, f. 53 (egg).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 159, pl. xlv.—Ib. Mex. B. II; Birds 7, pl. vii.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 339. Alcedo viridis, Vieillot, Nouv. Dict. XIX, 1818, 413 (Cassin). Ceryle cabanisi, Reichenb. Handb. sp. Orn. I, 27.—Caban. Mus. Hein. II, 147. Alcedo cabanisi, Tschudi.

Sp. Char. Head slightly crested. Upper parts, together with a pectoral and abdominal band of blotches, glossy green, as also a line on each side the throat. Under parts generally, a collar on the back of the neck, and a double series of spots on the quills, white. Female with a broad band of chestnut across the breast. Young of both sexes similar to the adult, but white beneath tinged with buff, and marking on breast more obsolete. Length about 8.00; wing, 3.14.

Hab. Rio Grande region of Texas and southward. Localities: Honduras (Scl. P. Z. S. 1858, 358); Bogota (Scl. P. Z. S. 1853, 130); Cordova (Scl. P. Z. S. 1856, 286); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 131); Honduras (Ibis, II, 117); S. E. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 472, breeds); Colorado River (Coues P. A. N. S. 1866, 59); Costa Rica (Lawr. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 118).

This species is much smaller than the Northern or Belted Kingfisher, and is easily distinguishable by the diagnostic marks already given. The sexes appear to differ, like those of C. alcyon, namely, the female being distinguished by a rufous pectoral band, which is wanting in the male.

Tschudi and Cabanis separate the northern from the more southern bird under the name of C. cabanisi; Tschudi retaining the name of C. americana for specimens resident in eastern South America. The differences are said to consist in the larger size, longer bill, greater extension of the white of the throat, and the decided spotting on the wing-coverts and quills of cabanisi. Though these differences are readily appreciable, they correspond so entirely with natural laws, distinguishing northern and southern individuals of most resident species, that it is only fair to consider them as merely modifications of a single species.

Several other species of Chloroceryle proper are found in Tropical America.

Habits. So far as is certainly known, this species is only found within our fauna as a bird of Texas, where it is occasional, rather than common, and confined to its western limits. From information received, I am confident that it will yet become known as at least of rare occurrence in Southern Florida, and possibly along the whole gulf coast. It was first noticed as a bird of the United States by Captain McCown, and added to our list by Mr. Lawrence, in 1851. It has since then been occasionally taken near the Rio Grande and in all the northeastern portions of Mexico. It is said to be found nearly throughout Mexico, and to be abundant also in Central America.

Mr. Dresser noticed several of these birds at Matamoras, in August, and afterwards found them common on the Nueces and the Leona Rivers, in which places they were breeding. In December he saw others near Eagle Pass. They were nowhere so abundant as the common belted species.

Dr. Coues states that they have been observed on several points on the Colorado River between Fort Mohave and Fort Yuma,—the only instances of their occurrence in the United States other than on the Rio Grande. We have but little information in regard to their habits, but there is no reason to suppose that they differ in this respect.

Mr. Salvin states that this species occurs abundantly everywhere upon the small streams in the Atlantic coast region, and in the interior of Central America. It was frequently observed near Dueñas, both on the Guacalate and on the outlet of Lake Dueñas. And Mr. J. F. Hamilton, in his Notes on the birds from the province of Santo Paulo, in Brazil, states that he found this species several times in the vicinity of shallow pools, most especially those of which the banks were well wooded. Several times he saw them perched on logs projecting a few feet out of the water. Dr. Burmeister speaks of this bird (var. americana) as the most common species of Kingfisher in Brazil. It is there met with everywhere near the small brooks, on the overhanging branches, and plunging into the water after its prey, which consists especially of small fish. It is less shy than other species, coming quite near to the settlements and being easily shot. Its nest is found in holes in the banks.

Mr. E. C. Taylor also mentions finding this species pretty common in the island of Trinidad, especially among the mangroves in the swamps and lagoons.

Eggs marked as those of Kingfishers were found in the collection of the late Dr. Berlandier, of Matamoras, and are presumed to belong to this species, though no notes in relation to their parentage, and none referring to this bird, were found among his papers. Except in size, they closely resembled eggs of the C. alcyon, being of a pure bright crystal-white color, and measuring 1.06 inches in length by .61 in breadth.

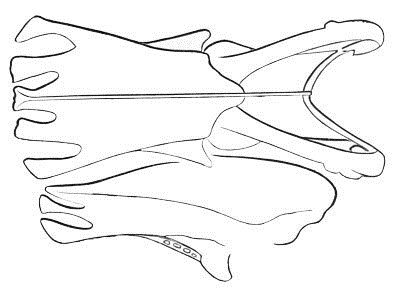

Sternum of Ceryle alcyon.

Family CAPRIMULGIDÆ.—The Goatsuckers

Char. Bill very short; the gape enormously long and wide, opening to beneath or behind the eyes. Culmen variable. Toes connected by a movable skin; secondaries lengthened; plumage soft, sometimes very full and loose, as in the Owls.

The preceding diagnosis in connection with that of the order will suffice to separate the Caprimulgidæ from their allies. Their closest relatives are the Cypselidæ, next to which perhaps may be reckoned the Trochilidæ.