полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

In defining the subdivisions of this family, we make use of an excellent monograph of the American species by Dr. Sclater, in Proceedings of the Zoölogical Society, London, 1866, 123. He establishes three subfamilies as follows:—

I. Podarginæ. Claw of middle toe not pectinated; outer toe with five phalanges. Sternum with two pairs of posterior fissures.

Outer pair of posterior sternal fissures much deeper than inner pair; tarsus long and naked. Eggs colorless. Podargus, Batrachostomus, Ægotheles, Old World.

Outer pair of posterior fissures much deeper than inner pair; tarsus extremely short and feathered. Nyctibius, New World.

II. Steatornithinæ. Claw of middle toe not pectinated; outer toe with five phalanges. Sternum with one pair of shallow posterior fissures. Eggs colorless. Steatornis, New World.

III. Caprimulginæ. Claw of middle toe pectinated; outer toe with four phalanges only. Sternum with one pair of shallow posterior fissures. Eggs colored (colorless in Antrostomus nuttalli, Baird).

a. Glabrirostres. Rictus smooth. Podager, Lurocalis, Chordeiles, New World. Lyncornis, Eurystopodus, Old World.

b. Setirostres. Rictus armed with strong bristles. Caprimulgus, Scotornis, Macrodipteryx, Old World; Antrostomus, Stenopsis, Hydropsalis, Heleothreptus, Nyctidromus, Siphonorhis, New World.

Dr. Sclater is of the opinion that Podargus may ultimately have to be placed in a different family from the Caprimulgidæ, with or without the other genera placed under Podarginæ; of these Nyctibius, the sole New World genus has species in Middle (including Jamaica) and South America. Steatornis caripensis, the single representative of the second subfamily, is found in Trinidad, Venezuela, and Colombia. It lives in caverns and deep chasms of the rocks, becoming excessively fat (whence the scientific name), and is said to feed on fruits. The bill is large and powerful, more like that of a Hawk than a Goatsucker.

Subfamily CAPRIMULGINÆ

Char. Outer toes with four digits only; claw of middle toe pectinated. Sternum with one pair only of sternal fissures or notches. Toes scutellate above. Hind toe directed a little more than half forward, nostrils separated; rather nearer the commissure than the culmen.

The Caprimulginæ have been divided by Dr. Sclater as follows:—

A. Glabrirostres. Rictus smoothI. Tarsus stout, longer than middle toe, entirely naked … Podager.

II. Tarsus moderate, shorter than middle toe, more or less clothed with feathers.

a. Tail short, almost square … Lurocalis.

b. Tail elongated, a little forked … Chordeiles.

B. Setirostres. Rictus bristledIII. Aerial. Tarsi short, more or less clothed.

a. Wings normal, second and third quills longest.

1. Tail moderate, rounded at tip … Antrostomus.

2. Tail elongated, even at tip … Stenopsis.

3. Tail very long, forked or bifurcate … Hydropsalis.

b. Wings abnormal in male; outer six quills nearly equal … Heleothreptus.

IV. Terrestrial. Tarsi elongated, naked.

a. Bill moderately broad; nasal aperture scarcely prominent … Nyctidromus.

b. Bill very broad; nasal aperture much projecting (Jamaica) … Siphonorhis.

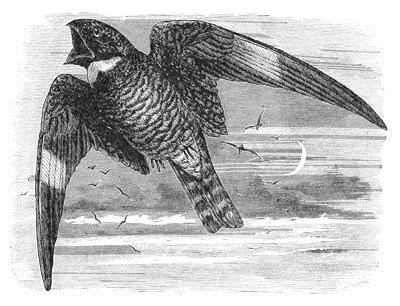

Chordeiles popetue.

1605 ♂

Of the genera enumerated above, only two certainly belong to the fauna of the United States (Chordeiles and Antrostomus), although there is some reason to suppose that Nyctidromus should be included, as among the manuscript drawings of Dr. Berlandier, of birds collected at Matamoras on the Lower Rio Grande, is one that can be readily referred to no other than N. albicollis.102 The briefest diagnoses of these three genera will be as follows:—

Chordeiles. Gape without bristles; tarsi moderate, partly feathered; tail narrow, slightly forked; plumage rather compact.

Antrostomus. Gape with bristles; tarsi moderate, partly feathered; tail broad, considerably rounded; plumage soft.

Nyctidromus. Gape with bristles; tarsi lengthened, bare; tail broad, rounded; plumage soft.

Genus CHORDEILES, SwainsonChordeiles, Swainson, Fauna Bor. Amer. II, 1831, 496. (Type, Caprimulgus virginianus.)

Gen. Char. Bill small, the nostrils depressed; the gape with feeble, inconspicuous bristles. Wings long, narrow, and pointed; the first quill nearly or quite equal to the second. Tail rather narrow, slightly forked; plumage quite compact. Habits diurnal or crepuscular.

Many species of this genus belong to America, although but two that are well characterized enter into the fauna of the United States. These are easily distinguished as follows:—

Species and VarietiesC. popetue. White patch on primaries extending over the five outer quills, anterior to their middle portion. No rufous spots on quills, anterior to the white patch.

a. Dark mottling predominating on upper parts; lower tail-coverts distinctly banded.

Wing, 8.00; tail, 4.40. Hab. Eastern Province of United States and Northwest coast … var. popetue.

Wing, 6.90; tail, 4.00. More rufous mottling on scapulars and jugulum, and a decided ochraceous tinge below. Hab. West Indies … var. minor.103

b. Light mottling predominating on upper parts; lower tail-coverts only very indistinctly and sparsely banded.

Size of var. popetue. Hab. Middle Province of United States … var. henryi.

C. acutipennis. White patch on primaries extending over only four outer quills, and beyond their middle portion; distinct rufous spots on quills, anterior to the white patch.

Wing, 6.20 to 6.50; tail, 3.90 to 4.10. Hab. South America … var. acutipennis.104

Wing, 7.00 to 7.30; tail, 4.40 to 4.75; Colors not appreciably different. Hab. Middle America, north into southern border of United States … var. texensis.

Chordeiles popetue, var. popetue, BairdNIGHT-HAWK; BULL-BATCaprimulgus popetue, Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. I, 1807, 56, pl. xxiv ♀. Chordeiles popetue, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 151.—Lord, Pr. R. A. Inst. IV, 1864, 113 (Br. Col. nesting).—Cooper & Suckley, 166.—Samuels, 122. Caprimulgus americanus, Wilson, V, 1812, 65, pl. cxl. f. 1, 2. Chordeiles americanus, DeKay, N. Y. Zoöl. II, 1844, 34, pl. xxvii. Caprimulgus virginianus, Brisson, II, 1760, 477 (in part only).—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 1834, 273, pl. cxlvii.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 1858.—Warthausen, Cab. J. 1868, 373 (nesting). Caprimulgus (Chordeiles) virginianus, Sw. F. Bor.-Am. II. 1831, 62. Chordeiles virginianus, Bon. List, 1838.—Aud. Birds Am. I, 1840, 159, pl. xliii.—Newberry, Zoöl. Cal. and Oregon Route, 79; Rep. P. R. R. Surv. VI, 1857. Long-winged Goatsucker, Pennant, Arctic Zoöl. II, 1785, 337.

Chordeiles popetue.

Sp. Char. Male, above greenish-black, but with little mottling on the head and back. Wing-coverts varied with grayish; scapulars with yellowish-rufous. A nuchal band of fine gray mottling, behind which is another coarser one of rufous spots. A white V-shaped mark on the throat; behind this a collar of pale rufous blotches, and another on the breast of grayish mottling. Under parts banded transversely with dull yellowish or reddish-white and brown. Wing-quills quite uniformly brown. The five outer primaries with a white blotch (about half an inch long) midway between the tip and carpal joint, not extending on the outer web of the outer quill. Tail with a terminal white patch, which does not reach the outer edge of the feathers. Female without the caudal white patch, the white tail-bands more mottled, the white of the throat mixed with reddish. Length of male, 9.50; wing, 8.20.

Hab. United States and north to Hudson Bay; in winter visits Greater Antilles, and southward to Central America (Rio Janeiro, Pelzeln); said to breed in Jamaica. In Rocky Mountains, replaced by the variety henryi. Localities: Trout Lake, H. B. T. (Murray, Edinb. Phil. Journ. 1860); Bahamas (Bryant, Bost. Soc. VII, 1859); Guatemala. (Scl. Ibis, II, 275); Cuba (Lawr.); Jamaica (March, P. A. N. S. 1863, 285, breeds); Matamoras (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 471, breeds); Rio Janeiro, January (Pelz., Orn. Bras. I, 14); Veragua (Salvin, P. Z. S. 1870, 203).

Habits. The common Night-Hawk of North America is a very common species throughout a widely extended area, and within the United States breeds wherever found. Its range extends from Florida and Texas to the extreme northern latitudes, and from the Atlantic at least to the great Central Plains. It has been found as far to the south as Panama.

At Matamoras Mr. Dresser found this species abundant during the summer season, and towards dusk thousands of these birds and of C. texensis and C. henryi might be seen flying in towards the river from the prairies, this one being the least common of the three. In Northern Florida it is also a common species, and I have rarely received any collection of eggs from that State without the eggs of this bird being found among them. They are known there as Bull-bats.

In many of its habits, as well as in its well-marked generic distinctions, this species exhibits so many and such well-marked differences from the Whippoorwill that there seem to be no good reasons for confounding two birds so very unlike. It is especially much less nocturnal, and has, strictly speaking, no claim to its common name, as indicating it to be a bird of the night, which it is not. It is crepuscular, rather than nocturnal, and even this habit is more due to the flight of the insects upon which it feeds at morning and at evening than to any organization of the bird rendering it necessary. It may not unfrequently be seen on the wing, even in bright sunny weather, at midday, in pursuit of its winged prey. This is especially noticeable with such birds as are wont to frequent our large cities, which may be seen throughout all hours of the day sailing high in the air. Generally, however, it is most lively early in the morning and just before nightfall, when its supply of insect food is most abundant. But it is never to be found on the wing after dark. As soon as the twilight deepens into the shades of night all retire to rest as regularly, if not at quite as early an hour, as other birds in regard to the diurnal habits of which there is no question.

This species appears to be equally abundant throughout the fur countries, where, Dr. Richardson states, few birds are better known. In the higher latitudes to which these birds resort the sun does not set during their stay, and all their pursuit of insects must be made by sunlight.

In the winter this species leaves the United States, retiring to Mexico, Central America, and the northern portions of South America. Specimens from Mexico were in the Rivoli collection. They were taken by Barruel in Nicaragua, by Salvin in Guatemala, in Jamaica by Gosse, and in Cuba by both Lembeye and Gundlach.

The movements, evolutions, and general habits of this species, in the pursuit of their prey, bear little resemblance to those of the Antrostomi, but are much more like those of the Falconidæ. They fly high in the air, often so high as to be hardly visible, and traverse the air, moving backward and forward in the manner of a Hawk. At times they remain perfectly stationary for several moments, and then suddenly and rapidly dart off, their wings causing a very peculiar vibratory sound. As they fly they utter a very loud and shrill cry which it is almost impossible to describe, but often appearing to come from close at hand when the bird is high in the air. Richardson compares this sound to the vibration of a tense cord in a violent gust of wind.

In some of the peculiarities of its breeding the Mosquito-Hawk displays several very marked variations of habit from the Whippoorwill. While the latter always deposits its eggs under the cover of shady trees and in thick woods, these birds select an open rock, a barren heath, or an exposed hillside for their breeding-place. This is not unfrequently in wild spots in the vicinity of a wood, but is always open to the sun. I have even known the eggs carelessly dropped on the bare ground in a corner of a potato-field, and have found the female sitting on her eggs in all the bright glare of a noonday sun in June, and to all appearance undisturbed by its brilliance. A more common situation for the eggs is a slight hollow of a bare rock, the dark weather-beaten shades of which, with its brown and slate-colored mosses and lichens, resembling both the parent and the egg in their coloring, are well adapted to screen them from observation or detection.

The great abundance of insect life of certain kinds in the vicinity of our large cities has of late years attracted these birds. Each summer their number in Boston has perceptibly increased, and through June and July, at almost all hours of the day, most especially in the afternoon, they may be seen or heard sailing high in the air over its crowded streets. The modern style of house-building, with flat Mansard roofs, has also added to the inducements, affording safe and convenient shelter to the birds at night, and serving also for the deposition of their eggs. In quite a number of instances in the summers of 1870 and 1871 they were known to lay their eggs and to rear their young on the flat roofs of houses in the southern and western sections of the city. I have also been informed by the late Mr. Turnbull, of Philadelphia, that the flat roofs of large warehouses near the river in that city are made similar use of.

If approached when sitting on her eggs, the female will suffer herself to be almost trodden on before she will leave them, and when she does it is only to tumble at the feet of the intruder and endeavor to draw him away from her treasures by well-feigned lameness and pretended disability. Her imitation of a wounded bird is so perfect as to deceive almost any one not aware of her cunning devices.

The eggs of this bird are always two in number, elliptical in shape, and equally obtuse at either end. They exhibit marked variations in size, in ground-color, and in the shades and number of their markings. In certain characteristics and in their general effect they are alike, and all resemble oblong-oval dark-colored pebble-stones. Their safety in the exposed positions in which they are laid is increased by this resemblance to the stones among which they lie. They vary in length from 1.30 to 1.13 inches, and in breadth from .84 to .94 of an inch. Their ground is of various shades of stone-color, in some of a dirty white, in others with a tinge of yellow or blue, and in yet others a clay-color. The markings are more or less diffused over the entire egg, and differ more or less with each specimen, the prevailing colors being varying shades of slate and of yellowish-brown. With all these variations the eggs are readily recognizable, and bear no resemblance to any others except those of texensis and henryi. From the former they are easily distinguished by the greater size, but from the latter they can only be separated by considerations of locality.

Chordeiles popetue, var. henryi, CassinWESTERN NIGHT-HAWKChordeiles henryi, Cassin, Illust. Birds of Cal. & Tex. I, 1855, 233.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 153, pl. xvii.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1866, 133.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 343.

Sp. Char. Similar to var. popetue, but the male considerably lighter, with a greater predominance of the light mottlings, producing a more grayish aspect; the female more rufous. Wing-patch of the male larger (at least an inch long), and, like the tail-patch, crossing the whole breadth of the feather.

Hab. Western Province of North America, except Pacific Coast region. Matamoras to San Antonio, Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 471); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 58).

In examining a large series of Night-Hawks, we find the differences indicated above, in specimens from the Black Hills, Rocky Mountains, and the adjacent regions, to be quite decided and constant. Skins, however, from Washington, Oregon, and California, seem darker even than the typical eastern. There is no prominent difference beyond the lighter colors of male, and greater distinctness, extent, and purity of the white or light markings, and in the white patches of wing and tail, crossing the outer webs of all the feathers; the general proportions and pattern of coloration being quite the same. It will therefore seem proper to consider C. henryi as a local race, characteristic of the region in which it occurs, and as such noteworthy, but not entitled to independent rank.

Another race, C. minor, Cab., similar to var. popetue, but considerably smaller (7.50, wing, 7.00), is resident in Cuba and Jamaica. C. popetue is also said to breed in the latter island, but minor is probably referred to.

Habits. This form, whether we regard it as a good species, or only a western race of the common Night-Hawk, was first described as a new variety by Mr. Cassin, in 1855, from specimens procured at Fort Webster, New Mexico, by Dr. Henry, in honor of whom it was named. Its claim to be considered a distinct race or species rests chiefly upon its constantly different colorations.

Dr. Cooper, who regarded this form not specifically distinct from the Night-Hawk, states that it is not found near the coast border of California.

Dr. Kennerly encountered it in abundance in the vicinity of Los Nogales, in Sonora, in June. Late in the afternoon they came in great numbers around the camp. They kept circling round and round, and approached the earth nearer and nearer with the declining sun.

Mr. Dresser found them very abundant at Matamoras, and as far east as the Sal Colorado, beyond which he did not meet with any. About dusk, thousands of these birds might be seen flying in towards the river from the prairies. At San Antonio, where Mr. Dresser found both C. popetue and C. texensis, he never procured a single specimen of this bird, nor did Dr. Heermann ever meet with one there.

Dr. Coues says these birds are abundant throughout the Territory of Arizona. At Fort Whipple it is a summer resident, arriving in April and remaining until October, being particularly numerous in August and September. Mr. Drexler made a large collection of these birds at Fort Bridger, in Utah, all of which showed such constant differences from eastern specimens as to indicate in his opinion the propriety of a specific separation.

An egg of this bird taken at Fort Crook, California, by Lieutenant Fulner, measures 1.25 inches in length by .92 of an inch in breadth. While resembling in general effect an egg of C. popetue, it is lighter in colorings, and varies from any of that bird I have ever seen. Its ground-color is that of clay, over which are diffused curious aggregations of small spots and cloudings of yellowish-brown, mingled with lilac. These markings are quite small and separate, but are grouped in such close proximity into several collections as to give them the appearance of large blotches; and the blending of these two shades is so general as to produce the effect of a color quite different from either, except upon a close inspection, or an examination through a magnifying glass.

This variety was met with at the Forks of the Saskatchewan, in June, 1858, by Captain Blakiston, and specimens were obtained on the Saskatchewan Plains, by M. Bourgeau, in the summer of the same year. The latter also procured its eggs. These are said to have been three in number, described as light olive, blotched with black more thickly at one end than the other. No mention of shape is made. This description, incomplete as it is, indicates a great dissimilarity with eggs of this bird, fully identified in the Smithsonian collection.

The western variety was met with by Mr. Ridgway throughout the entire extent of his route across the Great Basin. It bred everywhere, laying its eggs on the bare ground, beneath a sage-bush, usually on the foot-hills of the mountains, or on the mesas. In August and September they congregate in immense flocks, appearing in the evening. Not the slightest difference in habits, manners, or notes, was observed between this and the eastern Night-Hawk.

Chordeiles acutipennis, var. texensis, LawrenceTEXAS NIGHT-HAWKChordeiles brasilianus, Lawrence, Ann. N. Y. Lyceum, V, May, 1851, 114 (not of Gmelin).—Cassin, Ill. I, 1855, 238. Chordeiles sapiti, Bon. Conspectus Avium, I, 1849, 63. Chordeiles texensis, Lawrence, Ann. N. Y. Lyc. VI, Dec. 1856, 167.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 154, pl. xliv.—Ib. M. B. II, Birds, 7, pl. vi.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 345. Caprimulgus texensis, Warthausen, Cab. J. 1868, 376 (nesting).

Sp. Char. Much smaller than C. virginianus, but somewhat similar. White on the wing extending over only four outer primaries, the bases of which, as well as the remaining ones, with other quills, have round rufous spots on both webs. Under tail-coverts and abdomen with a strong yellowish-rufous tinge. Female more rufous and without the white spot of the tail. Length, 8.75; wing, 7.00.

Hab. Basins of Rio Grande, Gila, and Colorado Rivers, and west to Gulf of California; South as far, at least, as Costa Rica. Localities: Matamoras to San Antonio (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 471, breeds); W. Arizona (Coues; P. A. N. S. 1866, 58); Costa Rica (Lawr. An. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 120); Yucatan (Lawr. N. Y. Lyc. IX, 204).

The markings of this species are quite different from those of Chordeiles popetue. In average specimens the prevailing color above may be described as a mixed gray, yellowish-rusty, black, and brown, in varied but very fine mottlings. The top of the head is rather uniformly brown, with a few mottlings of grayish-rusty, although the concealed portion of the feathers is much varied. On the nape is a finely mottled collar of grayish and black, not very conspicuously defined, and rather interrupted on the median line. A similar collar is seen on the forepart of the breast. The middle of the back and the rump exhibit a coarser mottling of the same without any rufous. The scapulars and wing-coverts are beautifully variegated, much as in some of the Waders, the pattern very irregular and scarcely capable of definition. There are, however, a good many large round spots of pale yellowish-rusty, very conspicuous among the other markings. There is quite a large blotch of white on the wing, situated considerably nearer the tip than the carpal joint. It only involves four primaries, and extends across both outer and inner webs. The four first primaries anterior to the white blotches, and the remaining ones nearly from their tips, exhibit a series of large round rufous spots not seen in the other North American species. The other wing-quills have also similar markings. There is a large V-shaped white mark on the throat, as in C. virginianus, though rather larger proportionally. Posterior to this there are some rather conspicuous blotches of rufous, behind which is the obscure finely mottled collar of gray and brown already referred to. The breast and remaining under parts are dull white transversely banded with brown, with a strong tinge of yellowish-rufous on the abdomen, about the vent, and on the under tail-coverts. The tail is dark brown with about eight transverse bars of lighter; the last are white, and extend across both vanes; the others less continuous, and yellowish-rufous beneath as well as above, especially on the inner vane.