полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

The var. mexicanus, originally described by Mr. Swainson from Mexican specimens obtained near Real del Monte, has been ascertained to cross our boundaries, and is found in all the territory between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific, as far north as Washington Territory. Dr. Cooper has never met with this Hawk, but supposes its general habits, and especially those regulating its migrations, closely resemble those of A. cooperi, to which the bird itself, in all but size, is so similar. Dr. Coues speaks of it as a common resident species in Arizona. He states that he has seen young birds of this species, reared by the hand from the nest, become so thoroughly domesticated as to come to their master on being whistled for, and perch on his shoulder, or follow him when shooting small birds for their food. They were allowed their entire liberty. Their ordinary note was a shrill and harsh scream. A low, plaintive, lisping whistle was indicative of hunger.

Dr. Suckley, who met with this bird on Puget Sound, where a specimen was shot on a salt marsh, states that, while soaring about, it resembled in its motions the common Marsh Hawk, or Hen Harrier (Circus hudsonius).

Subgenus ASTUR, LacepedeAstur, Lacép. 1800. (Type, Falco palumbarius, Linn.)

Dædalion, Savig. 1809. Dædalium, Agass.

Sparvius, Vieill. 1816.

Aster, Swains. 1837.

Leucospiza, Kaup, 1844. (Type, Falco novæ-hollandiæ, Gmel.)

The characters of this subgenus have been sufficiently indicated on page 221, so that it is unnecessary to repeat them here. The species of Astur are far less numerous than those of Nisus, only about six, including geographical races, being known. They are found in nearly all parts of the world, except tropical America, the Sandwich Islands, and the East Indies.

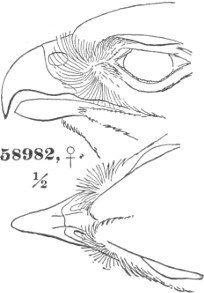

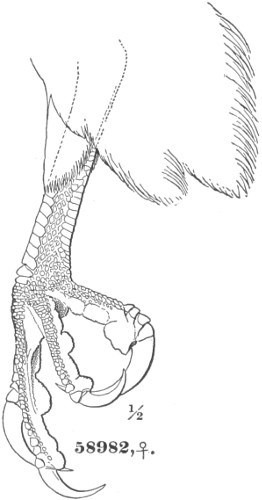

58982, ♀. ½

58982, ♀. ½

Astur atricapillus.

Species and Races

A. palumbarius. Wing, 12.00–14.50; tail, 9.50–12.75; culmen, .80–1.00; tarsus, 2.70–3.15; middle toe, 1.70–2.20. Fourth quill longest; first shortest. Adult. Above, continuously uniform slate-color, or brown; the tail with several more or less distinct broad bands of darker, and narrowly tipped with white. Beneath white, with transverse lines or bars of the same color as the upper surface. Top of the head blackish; a streaked whitish superciliary stripe. Young. Above much variegated with brown and pale ochraceous; bands on the tail more sharply defined. Beneath pale ochraceous, with longitudinal stripes of dark brown.

Adult. Above umber-brown, without conspicuously darker shaft-streaks; top of the head dull dusky. Markings on the lower parts in the form of sharply defined, broad, detached, crescentic bars, and of an umber tint; throat barred. Tail with five broad, well-defined bands of blackish. Wing, 12.25–14.25; tail, 9.40–11.10; culmen, .80–.95; tarsus, 2.80–3.15; middle toe, 1.80–2.20. Hab. Northern portions of the Old World … var. palumbarius.83

Adult. Above bluish slate-color, with conspicuous darker shaft-streaks; top of the head deep black; markings on the lower parts in the form of irregularly defined, narrow, zigzag bars, or fine lines, of a bluish-slaty tint; throat not barred. Tail with only about four indistinct bands of blackish. Wing, 12.00–14.70; tail, 9.50–12.75; culmen, .80–1.00; tarsus, 2.70–3.20; middle toe, 1.70–2.00. Hab. Northern portions of North America … var. atricapillus.

Astur palumbarius, var. atricapillus (Wils.)AMERICAN GOSHAWKFalco atricapillus, Wils. Am. Orn. 1808, pl. lii, f. 3.—Bonap. Nouv. Giorn. Pisa, XXV, pt. ii, p. 55. Astur atricapillus, Bonap. Os. Cuv. Règ. An. p. 33.—Ib. List, 1838, 5; Consp. 31.—Wils. Am. Orn. II, 284.—Kaup, Monog. Falc. Jardine’s Contr. Orn. 1850, 66.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 19, pl. ii, fig. 4 (ad.), f. 5 (♂ juv.).—Nutt. Man. 85.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 118.—Newb. P. R. Rep. VI, iv, 74.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. Rep. XII, ii, 144.—Lord, Pr. R. A. I. IV, 1860, 110.—Blakiston, Ibis, III, 1861, 316.—Gray, Hand List, I, 1869, 29.—Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, 17. Falco palumbarius, Sab. Frankl. Exp. 670.—Bonap. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. II, 28.—Aud. Edinb. J. Nat. Geog. Sc. III, 145.—Ib. B. Am. pl. cxli; Orn. Biog. II, 241.—Giraud, B. Long Isl’d, 18.—Peab. B. Mass. III, 77. Astur palumbarius, Sw. & Rich. F. B. A. II, pl. xxvi.—James. Wils. Am. Orn. I, 63.—Aud. Syn. B. Am. 18.—Brewer, Wils. Am. Orn. 685, pl. i, fig. 5.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. 63.

Sp. Char. Adult male (44,940, Boston, Mass.; E. A. Samuels). Above continuous bluish-slate, shafts of the feather inconspicuously black; tail darker and less bluish, tipped with white (about .25 of an inch wide) and crossed by five broad, faintly defined bars of blackish, these most distinct on inner webs (the first concealed by the upper coverts, the second partially so; the last, or subterminal one, which is about twice as broad as the rest, measuring about one inch in width). Primaries darker than the tail (but not approaching black). Forehead, crown, occiput, and ear-coverts pure plumbeous-black; feathers snowy-white beneath the surface, much exposed on the occiput; a broad conspicuous supraoral stripe originating above the posterior angle of the eye, running back over the ear-coverts to the occiput, pure white, with fine streaks of black; lores and cheeks grayish-white. Lower parts white; the whole surface (except throat and lower tail-coverts) covered with numerous narrow transverse bars of slate; on the breast these are much broken and irregular, forming fine transverse zigzags; posteriorly they are more regular, and about .10 of an inch wide, the white a very little more. Chin, throat, and cheeks without transverse bars, but with very sharp shaft-lines of black; breast, sides, and abdomen, a medial longitudinal broad streak of slate on each feather, the shaft black; on the tibiæ, where the transverse bars are narrower and more regular, the shaft-streaks are also finer; anal region finely barred; lower tail-coverts immaculate pure white. Lining of the wing barred more coarsely and irregularly than the breast; under surface of primaries with white prevailing, this growing more silvery toward the ends; longest (fourth) with six oblique transverse patches of slate, the outlines of which are much broken. Wing-formula, 4, 5, 3–6–2; 1=10. Wing, 13.00; tail, 9.50; tarsus, 3.70, naked portion, 1.35; middle toe, 2.00; inner, 1.21; outer, 1.37; posterior, 1.00.

No. 8,508 (Fort Steilacoom, Puget Sound, Washington Territory; Dr. Suckley. Var. striatulus, Ridgway). Similar to No. 44,940, but the upper surface more bluish, the shafts of the feathers more conspicuously black; the dorsal feathers nearly black around their borders. Tail-bands nearly obsolete. Lower parts with the ground-color fine bluish-ash, sprinkled transversely with innumerable zigzag dots of white, these gradually increasing in width posteriorly, where they take the form of irregular transverse bars; crissum sparsely and coarsely sprinkled with slaty. Each feather of the lower parts with a very sharply defined narrow shaft-stripe of deep black, these contrasting conspicuously with the bluish, finely marked ground-color. Under surface of primaries uniform slaty to their bases, the usual white spots being almost obsolete. Wing-formula, 4–5, 3–6–2–7–8–9, 1. Wing, 12.50; tail, 9.10; tarsus, 2.60, the naked portion, 1.40; middle toe, 1.75.

Adult female (12,239, Brooklyn, N. Y.; J. Ackhurst). Almost precisely similar to the male. Slate above less bluish; bands on tail more distinct, five dark ones (about .75 of an inch in width) across the brownish-slate; obscure light bands indicated on outer webs of primaries, corresponding with those on inner webs; lores more grayish than in male; bars beneath more regular; longitudinal streaks blacker and more sharply defined. Wing, 14.25; tail, 11.25; tarsus, 1.60–1.20; middle toe, 1.95; inner, 1.40; outer, 1.45; posterior, 1.30.

No. 59,892, (Colorado; F. V. Hayden, var. striatulus, Ridgway). Similar to male No. 8,508, described above, but differing as follows: interscapulars uniform with the rest of the upper surface; tail-bands appreciable, much broader than in ♀, No. 12,239, the subterminal one being 1.61, the rest 1.10, wide, instead of 1.10 and .70. The longest upper tail-coverts with narrow white tips; white spots on inner webs of primaries more distinct. Black shaft-streaks on lower surface broader and more conspicuous. Wing-formula, 4, 3, 5–6–2–7, 1=10. Wing, 14.70; tail, 11.50; tarsus, 2.50; the naked portion, 1.10; middle toe, 2.00.

Young male (second year, No. 26,920, Nova Scotia, June; W. G. Winton). Plumage very much variegated. Head above, nape, and anterior portion of the back, ochraceous-white, each feather with a central stripe of brownish-black, these becoming more tear-shaped on the nape. Scapulars, back, wing-coverts, rump, and upper tail-coverts umber-brown; the feathers with lighter edges, and with large, more or less concealed spots of white,—these are largest on the scapulars, where they occupy the basal and middle thirds of the feathers, a band of brown narrower than the subterminal one separating the two areas; upper tail-coverts similarly marked, but white edges broader, forming conspicuous terminal crescentic bars. Tail cinereous-umber, with five conspicuous bands of blackish-brown, the last of which is subterminal, and broader than the rest; tip of tail like the pale bands; the bands are most sharply defined on the inner webs, being followed along the edges by the white of the edge, which, frequently extending along the margin of the black, crosses to the shaft, and is sometimes even apparent on the outer web; the lateral feather has the inner web almost entirely white, this, however, more or less finely mottled with grayish, the mottling becoming more dense toward the end of the feather; the bands also cross more obliquely than on the middle feathers. Secondaries grayish-brown, with five indistinct, but quite apparent, dark bands; primaries marked as in the adult, but are much lighter. Beneath pure white, all the feathers, including lower tail-coverts, with sharp, central, longitudinal streaks of clear dark-brown, the shafts of the feathers black; on the sides and tibiæ these streaks are expanded into a more acuminate, elliptical form; the crissum only is immaculate, although the throat is only very sparsely streaked; on the ear-coverts the streaks are very fine and numerous, but uniformly distributed.

No. 18,404 (west of Fort Benton, on the Missouri, May 16, 1864; Captain Jas. A. Mullan, var. striatulus). Similar to No. 26,920, but colors much darker. Upper parts with dark brown prevailing, the pale borders to the feathers very narrow, and the basal very restricted and concealed; upper tail-coverts deep ashy-umber, tipped narrowly with white, and with large subterminal, transversely cordate, and other anterior bars of dusky. Tail ashy-brown, much darker than in No. 26,920, with five broad, sharply defined bands of blackish, without any distinct light bordering bar. White of the lower parts entirely destitute of any yellowish tinge, the stripes much broader than in No. 26,920, and deep brownish-black, the shafts not perceptibly darker; tibiæ with transverse bars of dusky; lower tail-coverts with transverse spots of the same. Wing, 12.25; tail, 9.70.

Young female (second year, No. 26,921, Nova Scotia; W. G. Winton). Head above, nape, rump, and upper tail-coverts, with a deep ochraceous tinge; the characters of markings, however, as in the male. Bands on the tail more sharply defined, the narrow white bar separating the black from the grayish bands more continuous and conspicuous; lateral feathers more mottled; grayish tip of tail passing terminally into white. Beneath with a faint ochraceous wash, this most apparent on the lining of the wings and tibiæ; streaks as in the male, but rather more numerous, the throat being thickly streaked.

No. 11,740 (Puget Sound, October 26, 1858; Dr. C. B. Kennerly. Var. striatulus). Similar to No. 18,404, but more uniformly blackish above; tip of tail more distinctly whitish; stripes beneath broader and deeper black, becoming broader and more tear-shaped posteriorly, some of the markings on the flanks being cordate, or even transverse. Wing-formula, 4, 5, 3–6, 2–7–8–9–10=1. Wing, 13.00; tail, 10.80; tarsus, 2.80; middle toe, 1.80.

Young female (first year, No. 49,662, Calais, Me.; G. A. Boardman). Differs from the female in the second year (No. 26,921) as follows: On the wings and upper tail-coverts the yellowish-white spots are less concealed, or, in fact, this forms the ground-color; secondary coverts ochraceous-white, with two very distant transverse spots of dark brown, rather narrower than the white spaces; tips of feathers broadly white; secondaries grayish-brown, tipped with white, more mottled with the same toward bases, and crossed by five bands of dark brown, the first two of which are concealed by the coverts, the last quite a distance from the end of the feathers; upper tail-coverts white, mottled on inner webs with brown, each with two transverse broad bars, and a subterminal cordate spot of dark brown, the last not touching the edge of the feather, and the anterior bars both concealed by the overlaying feather. Tail grayish-brown, tipped with white, and with six bands of blackish-brown; these bordered with white as in the older stage. Markings beneath as in the older stage, but those on the sides more cordate. Wing-formula, 4, 5, 3–6–7–2–8–9, 1, 10. Wing, 14.00; tail, 11.50.

In regard to the form indicated in the above descriptions as “var. striatulus, Ridgway,” I am as yet undecided whether to recognize it as a geographical race, or to merely consider the two adult plumages as representing different ages of the same form. Certain it is that there is a decided difference in the young plumage, between the birds of this species from the eastern portion of North America and those from the western regions; these differences consisting in the very much darker colors of the western individuals, as shown by the above descriptions. My first impression in regard to the adult dress, after making the first critical examination of the series at my command, was, that the coarsely mottled specimens were confined to the east, and that those finely mottled beneath were peculiar to the west; and this view I am not yet prepared to yield. I have never seen an adult bird from any western locality which agrees with the eastern ones described above; all partake of the same characters as those described, in being finely and faintly mottled beneath, with sharp black shaft-streaks, producing the effect of a nearly uniform bluish ground, the black streaks in conspicuous contrast, the tail-bands nearly obsolete, etc. But occasional, not to say frequent, individuals obtained in the eastern States, which agree in these respects with the western style, rather disfavor the view that these differences are regional, unless we consider that these troublesome individuals, being, of course, winter migrants, have strayed eastward from the countries where they were bred. The Colorado female described above exhibits a rather suspicious feature in having a single feather, on the lower parts, which is coarsely barred, as in the eastern style, while all the rest are finely waved and marbled as in the western. If this would suggest that the differences supposed to be climatic or geographical are in reality only dependent on age, it would also indicate that the finely mottled individuals are the older ones.

If future investigations should substantiate this suggestion as to the existence of an eastern and a western race of Goshawk in North America, they would be distinguished by the following characters:—

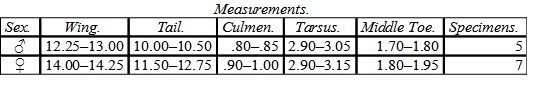

Var. atricapillus. Adult. Markings of the lower surface coarse and ragged; feathers of the pectoral region with broad medial longitudinal streaks of the same slaty tint as the transverse bars, and with only the shafts black. Tail-bands distinct. Young. Pale ochraceous markings prevailing in extent over the darker (clear grayish-umber) spotting. Stripes beneath narrow, clear brownish; those on the flanks linear. Wing, 12.25–14.25; tail, 10.00–12.75; culmen, .80–1.00; tarsus, 2.90–3.15; middle toe, 1.70–1.95. Hab. Eastern region of North America.

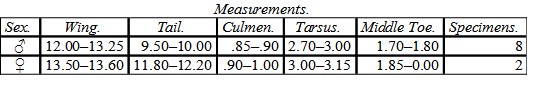

Var. striatulus. Adult. Markings of the lower parts fine and delicate, and so dense as to present the appearance of a nearly uniform bluish-ashy surface; feathers of the pectoral region without the medial stripes of slaty, but with broad shaft-streaks of deep black, contrasting very conspicuously with the finely mottled general surface. Tail-bands obsolete. Young. Darker (brownish-black) markings prevailing in extent over the lighter (nearly clear white) ones. Stripes beneath broad, brownish-black; those on the flanks cordate and transverse. Wing, 12.00–13.60; tail, 9.50–12.20; culmen, .85–1.00; tarsus, 2.70–3.15; middle toe, 1.70–.185. Hab. Western region of North America.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDVar. atricapillusNational Museum, 8; Philadelphia Academy, 7; New York Museum, 3; Boston Society, 2; G. N. Lawrence, 4; W. S. Brewer, 2; Museum, Cambridge, 2; R. Ridgway, 2. Total, 30.

National Museum, 9; R. Ridgway, 1; Museum, Cambridge, 1 (Massachusetts!). Total, 11.

Astur atricapillus.

Habits. The dreaded Blue Hen Hawk, as our Goshawk is usually called in New England, is a bird of somewhat irregular occurrence south of the 44th parallel. It occurs in the vicinity of Boston from November to March, but is never very common. In other parts of the State it is at times not uncommon at this season. It is common throughout Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Northern Maine, and may undoubtedly be found breeding in the northern portions of New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. In the summer of 1872, Mr. George Baxter, of Danville, Vt., procured a nest containing three young birds, which were sent to the New York Central Park. Mr. Downes speaks of it as “far too common” in the vicinity of Halifax, where it is very destructive to Ducks, Pigeons, and poultry. Mr. Boardman gives it as common near Calais, where it breeds, and where he has taken its eggs. Mr. Verrill mentions it as resident in Western Maine, where it is one of the most common Hawks. Mr. Allen found it usually rare near Springfield, but remarkably common during the winter of 1859–60. He afterwards mentions that since then, and for the last ten winters, he has known them to be quite common during several seasons. Mr. C. J. Maynard is confident that this species occasionally breed in Massachusetts. He once observed a pair at a locality in Weston, until the latter part of May. It was found breeding in Iowa by Mr. S. N. Marston. Mr. Victor Brooke records in the Ibis, 1870, p. 538, the occurrence, in Ireland, of an example of this species. It was shot in the Galtee Mountains, in February, 1870. The bird was a mature female, with the ovary somewhat enlarged. The stomach contained the remains of a rabbit.

On the Pacific coast it is comparatively rare in California, though much more abundant farther north, in Oregon and in Washington Territory. Dr. Cooper noticed several in the dense spruce forests of Washington Territory, and regarded it as a special frequenter of dark woods, where other Hawks are rarely seen. Dr. Suckley also obtained several specimens of this bird both at Fort Dalles and at Fort Steilacoom.

Sir John Richardson met with this Hawk and procured several specimens in the Arctic regions, and Captain Blakiston also met with it in the valley of the Saskatchewan. He states that it ranges throughout the interior from Hudson’s Bay to the Rocky Mountains and Mackenzie River. He found it breeding on the Saskatchewan, and one of his specimens was shot on its nest. The Goshawk was obtained at Sitka by Bischoff; and a pair was taken by Mr. Dall, April 24, 1867, within a few miles of Nulato Fort, on the Yukon River. The nest was on a large poplar, thirty feet above the ground, and made of small sticks. No eggs had been laid, but several nearly mature were found in the ovary of the female. The nest was on a small island in a thick grove of poplars, a situation which this species seemed to prefer. Mr. Dall adds that this was the most common Hawk in the valley of the Yukon, where it feeds largely on the White Ptarmigan (Lagopus albus), tearing off the skin and feathers, and eating only the flesh. Mr. Dall received skins from the Kuskoquim River, where it was said to be a resident species.

Dr. Suckley speaks of this Hawk as bold, swift, and strong, never hesitating to sweep into a poultry-yard, catch up a chicken, and make off with it almost in a breath. Its manner of seizing its prey was by a horizontal approach for a short distance, elevated but a few feet from the ground, a sudden downward sweep, and then, without stopping its flight, making its way to a neighboring tree with the struggling victim securely fastened in its talons. For strength, intrepidity, and fury, Dr. Suckley adds, it cannot be surpassed. It seems to display great cunning, seizing very opportune moments for its attacks. In one instance it was several days before he was able to have one of these birds killed, although men were constantly on the watch for it. So adroit was it in seizing opportunities to make its attacks, that it regularly visited the poultry-yard three times a day, and yet always contrived to escape unmolested. He found these birds much more plentiful during some months than at other times, and attributed it to their breeding in the retired recesses of the mountains, remaining there until their young were well able to fly, and then all descending to the open plains, where they obtain a more abundant supply of food.

Mr. Audubon states that in Maine the Goshawk was said to prey upon hares, the Canada and Ruffed Grouse, and upon Wild Ducks. They were so daring as to come to the very door of the farm-house, and carry off their prey with such rapidity as to baffle all endeavors to shoot them. Mr. Audubon found this Hawk preying upon the Wild Ducks in Canoe Creek, near Henderson, Ky., during a severe winter; as the banks were steep and high, he had them at a disadvantage, and secured a large number of them. They caught the Mallards with great ease, and, after killing them, tore off the feathers with great deliberation and neatness, eating only the flesh of the breast.

The flight of this bird he describes as both rapid and protracted, sweeping along with such speed as to enable it to seize its prey with only a slight deviation from its course, and making great use of its long tail in regulating both the direction and the rapidity of its course. It generally flies high, with a constant beat of the wings, rarely moving in large circles in the manner of other Hawks. It is described as a restless bird, vigilant and industrious, and seldom alighting except to devour its prey. When perching, it keeps itself more upright than most other Hawks.

Audubon narrates that he once observed one of these birds give chase to a large flock of the Purple Grakles, then crossing the Ohio River. The Hawk came upon them with the swiftness of an arrow; the Blackbirds, in their fright, rushing together in a compact mass. On overtaking them, it seized first one, and then another and another, giving each a death-squeeze, and then dropping it into the water. In this manner it procured five before the poor birds could reach the shelter of a wood; and then, giving up the chase, swept over the waters, picking up the fruits of its industry, and carrying each bird singly to the shore.

Mr. Audubon, who observed these Hawks in the Great Pine Forest of Pennsylvania, and on the banks of the Niagara River, near the Falls, describes a nest as placed on the branches of a tree, and near the trunk. It was of great size, and resembled that of a Crow in the manner of its construction, but was much flatter. It was made of withered twigs and coarse grass, with a lining of fibrous strips of plants resembling hemp. Another, found by Mr. Audubon in the month of April, contained three eggs ready to be hatched. In another the number was four.