полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

“Extremes of twenty-one eggs (mainly from Forts Yukon, Anderson, Resolution, and MacKenzie rivers): largest (10,687, Yukon, June), 1.75 × 1.28; smallest (8,808, Anderson River, June), 1.55 × 1.20. The ground-color varies from creamy-white to deep purplish-rufous, there being one egg (4,090, Great Slave Lake, June 6, 1860) entirely and uniformly of the latter color; the lightest egg (normally marked, 2,663, Saskatchewan) is creamy-white, thickly sprinkled with dilute and deep shades of sepia-brown, thickly on large end, and sparsely, as well as more finely, on the smaller end. The markings vary in color from dilute indian-red to blackish-chestnut.

“H. richardsoni is larger than columbarius, and probably has a larger egg. There are no eggs such as Richardson describes in the series of columbarius in the Smithsonian Collection.”

The var. richardsoni was recognized by Richardson as distinct from the more common columbarius; and a single specimen, killed at Carlton House, and submitted to Swainson, was pronounced by him, beyond doubt, identical with the common Merlin of Europe. Other specimens have since been procured, and are now in the Smithsonian Collection. They are recognized by Mr. Ridgway as identical with Richardson’s bird, but quite distinct from the Æsalon of authors. He has named the species in honor of its first discoverer. Of its history and habits little is known. A single pair were seen by Richardson in the neighborhood of Carlton House, in May, 1827, and the female was shot. In the oviduct there were several full-sized white eggs, clouded at one end with a few bronze-colored spots. Another specimen, probably also a female, was shot at the Sault St. Marie, between Lakes Huron and Superior, but this was not preserved.

Mr. Hutchins, in his notes on the Hudson’s Bay birds, states that the Pigeon Hawk “makes its nest on the rocks and in hollow trees, of sticks and grass, lined with feathers, laying from two to four white eggs, thinly marked with red spots.” As Hutchins has been found to be generally quite accurate in his statements, and as this description does not at all apply either to the nest or the eggs of the columbarius, it is quite possible that he may have mistaken this species for the Pigeon Hawk, and that this description of eggs and nests belongs not to columbarius, but to richardsoni.

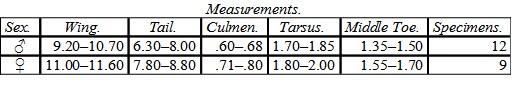

Subgenus RHYNCHOFALCO, RidgwaySpeciesF. femoralis. Wing, 9.30–11.60; tail, 6.30–8.80; culmen, .60–.80; tarsus, 1.62–2.00; middle toe, 1.35–1.70. Second and third quills longest; first equal to or shorter than fourth. Adult (sexes similar). Above uniform plumbeous, the secondaries broadly tipped with whitish. Tail darker terminally, crossed by about eight narrow, continuous bands of white, and tipped with the same. A broad postocular stripe, middle area of the auriculars, and entire throat and jugulum, white, unvariegated; the latter with a semicircular outline posteriorly, and the former changing to orange-rufous on the occiput, where the stripes of the two sides are confluent. Sides entirely uniform blackish (confluent on the middle of the abdomen), with narrow bars of white; posterior lower parts immaculate light ochraceous. Young similar, but the jugulum with longitudinal stripes of blackish. Hab. Whole of Tropical America, exclusive of the West Indies, north to the southern border of the United States.

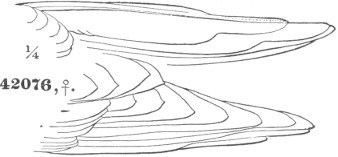

42076, ♀. ½

42076, ♀. ¼

42076, ♀.

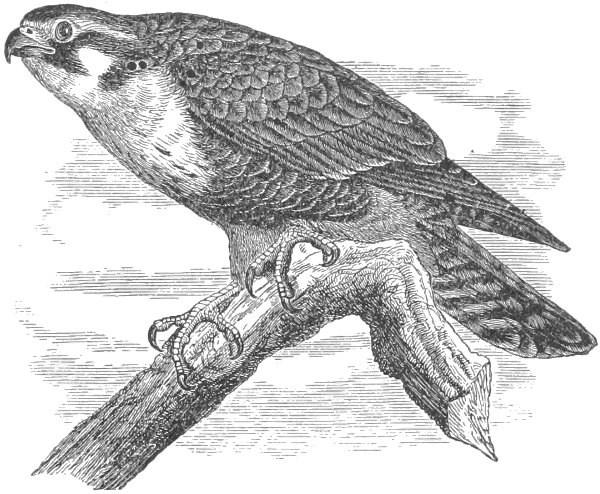

Falco (Rhynchofalco) femoralis, TemminckAPLOMADO FALCON

Falco femoralis, Temm. Pl. Col. 121, 343, 1824.—Spix, Av. Braz. I, 18 (quot. Pl. Cl. 121), 1824.—Vig. Zoöl. Journ. I, 339.—Steph. Zoöl. XIII, pt. 2, p. 39, 1826.—Less. Man. Orn. I, 79, 1828; Tr. Orn. p. 89, 1831.—Cuv. Reg. An. (ed. 2), I, 322, 1817.—Swains. Classif. B. II, 212, 1837.—Nordm. Erm. Reis. um die Erde, Atl. p. 16.—Bridg. Proc. Zoöl. Soc. pt. 11, p. 109; Ann. Nat. Hist. XIII, 499.—D’Orb. Voy. Am. Merid. Av. p. 116, 1835.—Tschudi, Consp. Av. Wieg. Arch. 1844, p. 266; Faun. Per. p. 108, 1844.—Cass. Proc. Ac. Nat. Sc. Philad. 1855, p. 178.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 88, 1855. Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, 14, pl. iii, f. 22. Hypotriorchis femoralis, Gray, Gen. B. fol. sp. 13, 1844; List B. Brit. Mus. p. 56, 1844.—Hartl. Syst. Ind. Azar. p. 3, 1847.—Cass. B. N. Am. p. 11, 1858.—Coues, Pr. Ac. Nat. Sc. Phil. 7, 1866.—Gray, Hand List, I, 21, 1869. Falco fuscocœrulescens, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. Hist. Nat. XI, 90, 1819. Falco cyanescens, Vieill. Enc. Méth. III, 1234 (No. 40, Azara, juv. teste, Hartl.). Falco thoracicus, Licht. Verz. Doubl. p. 62, 1823.

Sp. Char. Adult (sexes similar). Above uniform plumbeous, secondaries broadly whitish at ends; tail with continuous narrow bands of white. A postocular, broad stripe (changing to reddish on nape, where the two of opposite sides are confluent), middle area of auriculars, and entire throat and jugulum, white, unvariegated. Sides entirely uniform blackish (confluent on middle of abdomen), with narrow bars of white; posterior lower parts light ochraceous, immaculate. ♂. Wing, 9.90; tail, 6.70; tarsus, 1.62; middle toe, 1.45. ♀. Wing, 11.30; tail, 7.80; tarsus, 1.70; middle toe, 1.55.

Young. Similar to the adult, but with broad longitudinal stripes of blackish on the breast.

Adult male (No. 30,896, Mirador, E. Mexico; Dr. C. Sartorius). Above brownish-slate, becoming gradually darker anteriorly, the head above being pure dark plumbeous; on the rump and upper tail-coverts the tint inclines to fine cinereous. Secondaries passing very conspicuously into white terminally; primaries plumbeous-dusky, their inner webs with (the longest with twelve) very regular, narrow, transverse bars of white (the outer web plain). Lining of the wing white (becoming more ochraceous toward the edge); under coverts barred and serrated with dusky, the white, however, predominating. Tail black, basally with a perceptible plumbeous cast; crossed with eight narrow, transverse bands of white,—the first two of which are concealed by the coverts, the last terminal and about .27 of an inch in width; the rest are narrower, diminishing in width as they approach the base. Upper tail-coverts bordered terminally with ashy-white, the longer with one or two transverse bars of the same. Forehead (narrowly) white, this extending down across the lores to the angle of the mouth; a broad, conspicuous supraoral stripe, originating above the middle of the eye, and running back above the ear-coverts to the occiput (where the two of opposite sides are confluent), white, more fulvous-orange on the occiput; a broad dark plumbeous stripe running from the posterior angle of the eye back over upper edge of ear-coverts, and continuing (broadly) down the side of the neck; another, but much smaller one, of similar color, starting at lower border of bare suborbital space, passing downward across the cheeks, forming a “mustache,” leaving the middle area of the ear-coverts, the chin, throat, and whole breast, white, the pectoral portion defined with a semicircular outline posteriorly. Broad area covering the sides of the breast, sides, and flanks (meeting rather narrowly across the upper part of the abdomen), black, with narrow, rather indistinct, transverse bars of white. Femorals, tibiæ, abdomen, anal region, and lower tail-coverts fine ochraceous-rufous, palest posteriorly, the whole region immaculate. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–1, 5. Wing, 9.90; tail, 6.70; tarsus, 1.62; middle toe, 1.45.

Adult ♀ (42,076. Mirador; Sartorius). Similar to the male in almost every respect. Plumbeous above rather darker and more uniform, although the difference is scarcely perceptible. Secondaries more broadly tipped with white, and upper tail-coverts more conspicuously barred with the same. White bars of the black areas beneath scarcely observable. Tail with eight white bars, as in the male longest primary with fourteen white bars on inner web of longest. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–5=1. Wing, 11.30; tail, 7.80; tarsus, 1.70; middle toe, 1.55.

Juv. a (intermediate stage). ♂ (37,334, Mazatlan, W. Mexico; Col. A. J. Grayson). Plumbeous above darker and more brownish, uniform from rump to head, the former strongly tinged with rusty, this bordering the feathers. Tail darker and more brownish; white bars ten in number, instead of eight, narrower, and tinged with brownish; longest primary with thirteen bars of white on inner web. Lining of the wing black, leaving only a broad ochraceous stripe along the edge; feathers of the black portion with small circular white spots along their edges. Breast strongly tinged with ochraceous, and with large longitudinal blotches of black of cuneate form, and so crowded as to give almost the predominating color; the black patches lack entirely the white bars. Wing-formula, 3=2–4–1–5. Wing, 10.00; tail, 7.20.

♀ (55,019, Mazatlan, Grayson). Similar to the last, but lacking the rusty tinge on the rump; tail with eight white bars, as in the adult; pectoral stripes narrower and less numerous than in the preceding, and white bars distinguishable on the black areas. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–1–5. Wing, 11.30; tail, 8.20.

b (first plumage). ♂ (45,693 and 49,508, Buenos Ayres, Conchitas; William H. Hudson). Similar to immature male (37,334). Above dull umber-drab, darker on the head; feathers of back, scapular, rump, and wings fading on edges; rump much tinged with rusty, this bordering the feathers. Tail with nine very obsolete, narrow, dull white bars, these not touching the edge of the feather on either web. Longest primary with ten transverse white bars on inner web. Beneath pale ochraceous, almost as deep anteriorly as posteriorly; dark areas restricted to a large patch on each side, and dull dark brown (very similar to the wings), instead of black, and scarcely varied; breast and upper part of abdomen (between the blackish lateral patches) with large longitudinal cuneate blotches of the same. “Winter visitor.”

Hab. Whole of South America; northward through Central America and Mexico, across the Rio Grande, into Texas and New Mexico.

Localities: Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 219); Cathagena (Cassin, Pr. An. N. S. 1860, 132); La Plata (Burm. Reise, 437); Mexiana (Scl. & Salv. 1867, 590); Brazil (Pelz. O. Bras. I, 4); Buenos Ayres (Scl. & Salv. 1868, 143); Chile (Philippi); W. Peru (Scl. & Salv. 1858, 570; 1869, 155); Venezuela (Scl. & Salv. 1869, 252).

A specimen from Paraguay (58,738, ♂ ? Capt. T. J. Page, U. S. N.) has the slaty above lighter than in the Mirador male, approaching to ash. The white bars on the black side-patches are very numerous and regular; the white of the forehead is more sharply defined, and the deep rufescent-ochre of the posterior portion of the postocular stripe is even deeper than that of the tibiæ, etc.; the breast has a few narrow blackish streaks. The bars on wings and tail, however, are as in Mexican examples. This specimen probably denotes greater age than any other in the series.

Another specimen (29,809, ♀, Mirador), perhaps very young, is rather different from the others in the coloration of the lower parts; the rufous of the posterior portions is very deep, and the anterior light places are much tinged with ochraceous, the supraloral stripe being tinged throughout with the same; across the breast is a series of small tear-shaped spots of black, forming an imperfect band; there are, however, no other differences.

Nos. 29,520 (♀, Chile, Berlin Museum) and 29,521 (♂, Venezuela) differ from the rest only in a deeper tinge of ochraceous anteriorly beneath, the occipital stripes being very red.

No. 18,497 (♂, from the Rio Pecos, Texas) is in the plumage described as that of the young male, having the rusty tinge on rump, and more numerous bands on tail; the breast is almost as deeply ochraceous as the tibiæ, and the broad black patches of the sides scarcely meet across the abdomen, being there broken into streaks.

Falco femoralis.

A female, nearly adult, from Buenos Ayres (45,692, Conchitas; W. H. Hudson), has the feathers of the upper parts faintly edged with white; the rump and upper tail-coverts conspicuously barred with the same. The head above is decidedly more bluish than in northern examples, each feather with a shaft-line of black. The tail has only seven white bars,—these, however, very sharply defined, and very pure white; the longest primary has eleven white bars. The lower plumage is similar to that of the immature male from the Rio Pecos, Texas (No. 18,497). This specimen has the second and third quills equal.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 14; Boston Society, 5; Philadelphia Academy, 2; New York Museum, 1; G. N. Lawrence, 1; R. Ridgway, 2. Total, 25.

Habits. Only two specimens of this Hawk have been taken within the limits of the United States. One was obtained by Dr. Heermann on the vast plains of New Mexico, near the United States boundary-line. It appeared to be flying over the prairies in search of small birds and mice, at times hovering in the manner of the common Sparrow Hawk (Tinnunculus sparverius). It appears to be resident throughout a large part of Mexico, and in Central and South America. The other is from the Rio Pecos of Texas, collected by Dr. W. W. Anderson.

Mr. Darwin, in his Zoölogy of the Voyage of the Beagle, mentions obtaining one specimen in a small valley on the plains of Patagonia, at Port Desire, in latitude 47° 44′ south. M. D’Orbigny supposed latitude 34° to be the extreme southern limit of the species. Lieutenant Gilliss brought specimens from Chile.

Mr. Darwin states that the F. femoralis nests in low bushes, this corresponding with the observations of Mr. Bishop. He found the female sitting on her eggs in the beginning of January. According to M. D’Orbigny, it prefers a dry, open country with scattered bushes, which Mr. Darwin confirms. Mr. Bishop informs me that he met with this Hawk in the greatest abundance upon those vast plains of South America known as the Pampas, in which no trees except the ombû are found, and that it there nests exclusively on the tops of low bushes, hardly more than a foot or two from the ground. The bird was not at all shy, like most Hawks, but was easily approached so nearly as to be readily recognized.

Mr. Bridges states, in the Proceedings of the London Zoölogical Society (1843, p. 109), that the H. femoralis is trained in some parts of South America for the pursuit of smaller gallinaceous birds, and that it is highly esteemed by the Chilian falconers. It very soon becomes quite docile, and will even follow its master within a few weeks of its capture.

I am indebted to Mr. N. H. Bishop for specimens of the eggs of this Hawk obtained by him on the Pampas. The nest contained but two, and was built on the top of a low bush or stunted tree, hardly two feet from the ground. It was constructed, with some pains and elaboration, of withered grasses and dry leaves.

The eggs measure, one 1.81 inches in length by 1.69 in breadth, the other 1.78 by 1.63. This does not materially vary from the measurement given by Darwin. The ground-color of the egg is white. This, however, is so thickly and so generally studded with fine brown markings, that the white ground to the eye has a rusty appearance, and its real hue is hardly distinguishable. Over the entire surface of the egg is distributed an infinite number of fine dottings, of a color most nearly approaching a raw terra-sienna brown. Over this again are larger blotches, lines, and splashes of a handsome shade of vandyke-brown. In one egg these larger markings are much more frequent than in the other. The latter is chiefly marked with the finer rusty dottings, and has a more dingy appearance.

Subgenus TINNUNCULUS, VieillotTinnunculus, Vieill. 1807. (Type, Falco tinnunculus, Linn. Tinnunculus alaudarius, Gmel.)

? Tichornis, Kaup, 1844. (Type, Falco cenchris, Naum.)

Pœcilornis, Kaup, 1844. (Type, Falco sparverius, Linn.)

The characters of this subgenus have been sufficiently defined in the diagnosis on page 1427, so that it will be necessary for me only to add a few less important ones.

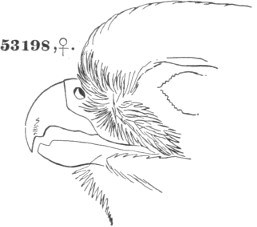

53198, ♀.

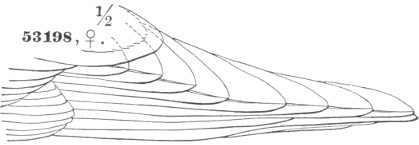

53198, ♀. ½

53198, ♀.

53198, ♀. ½

Tinnunculus sparverius.

The subgenus Tinnunculus is one which is well characterized by peculiarities of manners and habits as well as by features of structure. The species are the most arboreal of the Falcons, and their curious habit of poising in a fixed position as they hover over some object of food which they are watching is probably peculiar to them, and has been remarked of the Old World as well as of the American species. In their structure they are the most aberrant members of the subfamily belonging to the Northern Hemisphere and in their weak bill and feet, lengthened tarsi, obtusely tipped quills, more rounded wings, and more lengthened tail, exhibit a decided step toward Hieracidea, an Australian genus which is almost exactly intermediate in all the characters of its external structure between the true Falcons and the South American genus Milvago, of the Polyborine group.

The subgenus is most largely developed in the Old World, where are found about a dozen nominal species, of which perhaps one half must be reduced to the rank of geographical races. America possesses three species, two of which are restricted to the West India islands, while the other extends over the entire continent.

There is no reason whatever for separating the American species from those of the Old World, and the subgenus Pœcilornis, established upon these by Kaup, is not tenable.

Since the publication of my first paper upon the American forms of Tinnunculus,59 a large amount of additional material has fallen under my observation; the total number of examples critically examined and compared together amounting to over three hundred and fifty skins of which I have kept a record, besides many others which have come casually to my notice. This abundant material merely confirms the views I first expressed, in the paper alluded to, regarding the number and definition of the forms; their comparative relation to each other being the only respect in which I have reason to modify my arrangement.

In my first paper on the American Tinnunculi, three distinct species were recognized; one (sparverius) belonging to the whole of Continental America and the Lesser Antilles, one (leucophrys, Ridgway) to Cuba and Hayti, and one (sparveroides, Vig.) peculiar to Cuba. The first is one modified in different climatic regions into several geographical races, as follows: Var. sparverius, L., North and Middle America, exclusive of the gulf and Caribbean coast region; var. isabellinus, Swains., the eastern coast region of Tropical America, from Guiana to Florida; var. dominicensis, Gmel. (Lesser Antilles); var. australis, Ridgw. (South America in general); and var. cinnamominus, Swains. (Chile and Western Brazil). That each of these races is well characterized, the evidence of a series abundantly sufficient to determine this point enables me to assert without reserve; for I find in each instance that the characters diagnosed in my synopsis hold good as well with a large series as with a few specimens.

The following synopsis, essentially the same as that before published, may, to most persons, explain satisfactorily my reasons for recognizing so many races of T. sparverius,—a proceeding which, I am sorry to say, does not meet with favor with all ornithologists.60 Though there are at the present time three well-characterized or permanently differentiated species of Tinnunculus on the American continent, yet it is, to my mind, certain that these have all descended from a common ancestral stock, for evidence in proof of this is found in many specimens which I consider at least strongly “suggestive” of this fact; some specimens of var. isabellinus from Florida having blue feathers interspersed over the rump, thereby showing an approximation toward the uniformly blue upper surface of the adult male of T. sparveroides of the neighboring island of Cuba; while in the latter bird the embryonic plumage of the male is very similar to the permanent condition of the male of sparverius.

Synopsis of the American SpeciesA. Back always entirely rufous (with or without black bars.) Lower parts white, or only tinged with ochraceous; front and auriculars distinctly whitish.

a. Inner webs of primaries barred entirely across, with white and dusky; “mustache” across the cheeks conspicuous; no conspicuous superciliary stripe of white.

1. T. sparverius.61 Crown bluish, with or without a patch of rufous. ♂. Wings and upper part of head slaty, or ashy-blue; scapulars, back, rump, and tail reddish-rufous; primaries, basal half of the secondaries, and a broad subterminal zone across the tail, black. ♀. The bluish, except that of the head, replaced by rufous, which is everywhere barred with blackish, and of a less reddish cast. Hab. Entire continent of America, also Lesser Antilles, north to St. Thomas.

b. Inner webs of primaries white, merely serrated along the shaft with dusky; “mustache” obsolete or wanting; a conspicuous superciliary stripe of white.

2. T. leucophrys.62 Similar to sparverius, except as characterized above. Hab. Cuba and Hayti.

B. Back rufous only in the ♀. Lower parts deep ferruginous-rufous; front and auriculars dusky.

3. T. sparveroides.63 ♂. Above, except the tail, entirely dark plumbeous, with a blackish nuchal collar; primaries and edges and subterminal portion of tail-feathers, black. Beneath deep rufous (like the back of sparverius and leucophrys), with a wash of plumbeous across the jugulum; throat grayish-white. Inner webs of primaries slaty, with transverse cloudings of darker. ♀. Differing from that of the above species in dark rufous lower parts and dusky, mottled inner webs of primaries. Second and third quills longest; first shorter than or equal to fourth. Hab. Cuba (only?).

The distinguishing characters of F. sparverius having been given in the foregoing synopsis, I will here consider this species in regard to the modifications it experiences in the different regions of its geographical distribution.

The whole of continental America, from the Arctic regions to almost the extreme of South America, and from ocean to ocean, is inhabited, so far as known, by but this one species of Tinnunculus. But in different portions of this vast extent of territory the species experiences modifications under the influence of certain climatic and other local conditions, which are here characterized as geographical races; these, let me say, present their distinctive characteristics with great uniformity and constancy, although the differences from the typical or restricted sparverius are not very great. The F. sparverius as restricted, or what is more properly termed var. sparverius, inhabits the whole of North and Middle America (both coasts included, except those of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea), south to the Isthmus of Panama. Throughout this whole region it is everywhere nearly the same bird. This variety appears to represent the species in its greatest purity, being a sort of central form from which the others radiate. The most typical examples of the var. sparverius are the specimens in the large series from the elevated regions or plateau of Mexico and Guatemala. In these the rufous of the crown is most extended (in none is it at all restricted), and the ashy portions are of the finest or bluest and lightest tint.