полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

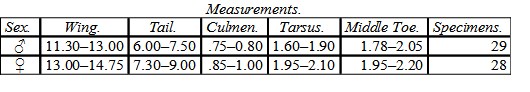

Mr. Cassin’s type of “nigriceps” (13,856, ♂, July), from Chile, is before me, and upon comparison with adult males from Arctic America presents no tangible differences beyond its smaller size; the wing is a little more than half an inch, and the middle toe less than the eighth of an inch, shorter than in the smallest of the North American series,—a discrepancy slight indeed, and of little value as the sole specific character; the plumage being almost precisely similar to that of the specimen selected for the type of the description at the head of this article. In order to show the little consequence to be attached to the small size of the individual just mentioned, I would state that there is before me a young bird, received from the National Museum of Chile, and obtained in the vicinity of Santiago, which is precisely similar in plumage to the Nevada specimen described, and in size is even considerably larger, though it is but just to say that it is a female; the wing measures 13.25, instead of 12.50, and the middle toe, 2.00, instead of 1.85. No. 37,336, Tres Marias Islands, Western Mexico,—a young male in second year,—has the wing just the same length as in the smallest North American example, while in plumage it is precisely similar to 26,785, of the same age, from Jamaica. No. 4,367, from Puget’s Sound, Washington Territory,—also a young male,—has the wing of the same length as in the largest northern specimen, while the plumage is as usual.

Two adult females from Connecticut (Nos. 28,099 and 32,507, Talcott Mt.) are remarkable for their very deep colors, in which they differ from all other North American examples which I have seen, and answer in every particular to the description of F. cassini, Sharpe, above cited. The upper surface is plumbeous-black, becoming deep black anteriorly, the head without a single light feather in the black portions; the plumbeous bars are distinct only on the rump, upper tail-coverts, and tail, and are just perceptible on the secondaries. The lower parts are of a very deep reddish-ochraceous, deepest on the breast and abdomen, where it approaches a cinnamon tint,—the markings, however, as in other examples. They measure, wing, 14.75; tail, 7.50; culmen, 1.05–1.15; tarsus, 2.00; middle toe, 2.30. They were obtained from the nest, and kept in confinement three years, when they were sacrificed to science. The unusual size of the bill of these specimens (see measurements) is undoubtedly due to the influence of confinement, or the result of a modified mode of feeding. The specimens were presented by Dr. S. S. Moses, of Hartford.

An adult male (No. 8,501) from Shoal-water Bay, Washington Territory, is exactly of the size of the male described. In this specimen there is not the slightest creamy tinge beneath, while the blue tinge on the lower parts laterally and posteriorly is very strong. No. 52,818, an adult female from Mazatlan, Western Mexico, has the wing three quarters of an inch shorter than in the largest of four northern females, and of the same length as in the smallest; there is nothing unusual about its plumage, except that the bars beneath are sparse, and the ochraceous tinge quite deep. No. 27,057, Fort Good Hope, H. B. T., is, however, exactly similar, in these respects, and the wing is but half an inch longer. In No. 47,588, ♂, from the Farallones Islands, near San Francisco, California, the wing is the same length as in the average of northern and eastern specimens, while the streaks on the jugulum are nearly as conspicuous as in a male from Europe.

In conclusion, I would say that the sole distinguishing character between the Peregrines from America and those from Europe, that can be relied on, appears to be found in the markings on the breast in the adult plumage; in all the specimens and figures of var. communis that I have seen, the breast has the longitudinal dashes very conspicuous; while, as a general rule, in anatum these markings are entirely absent, though sometimes present, and occasionally nearly as distinct as in European examples. Therefore, if this conspicuous streaking of the breast is found in all European specimens, the American bird is entitled to separation as a variety; but if the breast is ever immaculate in European examples, then anatum must sink into a pure synonyme of communis. The var. melanogenys is distinguished from both communis and anatum by the black auriculars, or by a greater amount of black on the side of the neck, and by more numerous and narrower bars on the under surface. In the former feature examples of anatum from the southern extremity of South America approach quite closely to the Australian form, as might be expected from the relative geographical position of the two regions. The var. minor is merely the smaller intertropical race of the Old World, perhaps better characterized than the tropical American form named F. nigriceps by Cassin, the characters of which are so unimportant, and withal so inconstant, as to forbid our recognizing it as a race of the same rank with the others.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 45; Boston Society, 4; Philadelphia Academy, 22; Museum Comp. Zoöl. 5; New York Museum, 3; G. N. Lawrence, 6; R. Ridgway, 3. Total, 88.

? ? Accipiter falco niger, Briss. Orn. I, 337. ? ? Falco niger, Gmel. S. N. 1789, 270. Falco polyagrus, Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. pl. xvi (dark figure).

Sp. Char. In colors almost exactly similar to F. gyrfalco, var. labradora. Above continuous dark vandyke-brown, approaching brownish-black on the head, which is variegated only on the gular region, and inclining to grayish-brown on the tail; the whole surface entirely free from spots or markings of any kind. Beneath similar in color to the upper parts, but the feathers edged with whitish, this rather predominating on the throat; flanks and tibiæ with roundish white spots; lower tail-coverts with broad transverse bars of white. Lining of the wing with feathers narrowly tipped with white; inner webs of primaries with narrow, transverse elliptical spots of cream-color; inner webs of tail-feathers with badly defined, irregular, similar spots, or else with these wanting, the whole web being plain dusky-brown.

No. 12,022 (♀, Oregon; T. R. Peale). Wing, 15.00; tail, 8.50; culmen, .95; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 2.15. (Figured by Cassin as F. polyagrus, in Birds of California and Texas, pl. xvi.)

No. 45,814 (♀, Sitka, Alaska, May, 1866; F. Bischoff). Wing, 14.90; tail, 8.50; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 2.20. The two similar in color, but in the latter the white streaks on the lower parts a little broader, and the middle of the auriculars slightly streaked.

Hab. Northwest coast of North America, from Oregon to Sitka.

This curious race of Falco communis is a good illustration of the climatic peculiarity of the northwest coast region, to which I have often referred before; the same melanistic tendency being apparent in birds of other species from the same region, as an example of which I may mention the Black Merlin (Falco æsalon, var. suckleyi), which is a perfect miniature of the present bird.

Habits. The Great-footed Hawk of North America is very closely allied to the well-known Peregrine Falcon of Europe, and so closely resembles it that by many writers, even at the present day, it is regarded as identical with it. Without doubt, the habits of the two races are very nearly the same, though the peculiarities of the North American bird are not so well known as are those of the European. In its distribution it is somewhat erratic, for the most part confined to the rocky sea-coast, the river-banks, and the high ground of the northeastern parts of America. It is known to breed in a few isolated rocky crags in various parts of the country, even as far to the south as Pennsylvania, and it occurs probably both as migrant and resident in several of the West India Islands, in Central and in South America. A single specimen was taken by Dr. Woodhouse in the Creek country of the Indian Territory. Two individuals are reported by Von Pelzeln as having been taken in Brazil. The Newtons met with it in St. Croix. Mr. Gosse found it in Jamaica, and Dr. Gundlach gives it as a bird of Cuba. Jardine states it to be a bird of Bermuda, and also that it has been taken in the Straits of Magellan. A single specimen was taken at Dueñas, Guatemala, in February, by Mr. Salvin.

On the Pacific coast this Falcon has been traced as far south as the limit of the land. Dr. Cooper met with only two pairs, in March, 1854, frequenting a high wooded cliff at Shoal-water Bay. Dr. Suckley procured a single specimen from Steilacoom. Dr. Cooper states that the habits of these corresponded with those described for the F. anatum and F. peregrinus, and that, like these Falcons, it is a terror to all land animals weaker than itself. It is said to breed on the rocky cliffs of the Pacific.

An individual of this bird was taken by Colonel Grayson at the Tres Marias Islands. When shot, it was endeavoring to capture a Sparrow-hawk, indicating its indifference as to the game it pursues. He adds that this bird attacks with vigor everything it sees, from the size of a Mallard Duck down, and is the terror of all small birds. Its range must be very great, as it often ventures far out to sea. On his passage from Mazatlan to San Francisco, in 1858, on the bark Carlota, one of these Falcons came on board more than a hundred miles off the coast of Lower California, and took up its quarters on the main-top yard, where it remained two days, during which time it captured several Dusky Petrels. It would dart headlong upon these unsuspecting birds, seldom missing its aim. It would then return to its resting-place and partly devour its prize. At other times it dropped its victims into the sea in wanton sport. Finally, as if tired of this kind of game, it made several wide circles around the ship, ascended to a considerable height, and departed in the direction of the Mexican shore.

This Falcon is found along the Atlantic coast from Maine to the extreme northern portion, breeding on the high rocky cliffs of Grand Menan and in various favorable situations thence northward. A few breed on Mount Tom, near the Connecticut River in Massachusetts, on Talcott Mountain in Connecticut, in Pennsylvania, and near Harper’s Ferry, in Maryland.

Mr. Boardman has several times taken their eggs from the cliffs of Grand Menan, where they breed in April, or early in May. In one instance he found the nest in close proximity to that of a pair of Ravens, the two families being apparently on terms of amity or mutual tolerance.

For several years two or more pairs of these birds have been known to breed regularly on Mount Tom, near Northampton. The nests were placed on the edges of precipitous rocks very early in the spring, the young having been fully grown by the last of June. Their young and their eggs have been taken year after year, yet at the last accounts they still continued to nest in that locality. Dr. W. Wood has also found this species breeding on Talcott Mountain, near Hartford. Four young were found, nearly fledged, June 1. In one instance four eggs were taken from a nest on Mount Tom, by Mr. C. W. Bennett, as early as April 19. This was in 1864. Several times since he has taken their eggs from the same eyrie, though the Hawks have at times deserted it and sought other retreats. In one year a pair was twice robbed, and, as is supposed, made a third nest, and had unfledged young as late as August. Mr. Allen states that these Hawks repair to Mount Tom very early in the spring, and carefully watch and defend their eyrie, manifesting even more alarm at this early period, when it is approached, than they evince later, when it contains eggs or young. Mr. Bennett speaks of the nest as a mere apology for one.

This Hawk formerly nested on a high cliff near the house of Professor S. S. Haldeman, Columbia, Penn., who several times procured young birds which had fallen from the nest. The birds remained about this cliff ten or eleven months of the year, only disappearing during the coldest weather, and returning with the first favorable change. They bred early in spring, the young leaving the nest perhaps in May. Professor Haldeman was of the opinion that but a single pair remained, the young disappearing in the course of the season.

Sir John Richardson, in his Arctic expedition in 1845, while descending the Mackenzie River, latitude 65°, noticed what he presumed to be a nest of this species, placed on the cliff of a sandstone rock. This Falcon was rare on that river.

Mr. MacFarlane found this species not uncommon on the banks of Lockhart and Anderson Rivers, in the Arctic regions. In one instance he mentions finding a nest on a cliff thirty feet from the ground. There were four eggs lying on a ledge of the shale of which the cliff was composed. Both parents were present, and kept up a continued screaming, though at too great a distance for him to shoot either. He adds that this bird is by no means scarce on Lockhart River, and he was informed that it also nests along the ramparts and other steep banks of the Upper Anderson, though he has not been able to learn that it has been found north of Fort Anderson. In another instance the nest was on a ledge of clayey mud,—the eggs, in fact, lying on the bare ground, and nothing resembling a nest to be seen. A third nest was found on a ledge of crumbling shale, along the banks of the Anderson River, near the outlet of the Lockhart. This Hawk, he remarks, so far as he was able to observe, constructs no nest whatever. At least, on the Anderson River, where he found it tolerably abundant, it was found to invariably lay its eggs on a ledge of rock or shale, without making use of any accessory lining or protection, always availing itself of the most inaccessible ledges. He was of the opinion that they do not breed to the northward of the 68th parallel. They were also to be found nesting in occasional pairs along the lime and sandstone banks of the Mackenzie, where early in August, for several successive years, he noticed the young of the season fully fledged, though still attended by the parent birds.

In subsequent notes, Mr. MacFarlane repeats his observations that this species constructs no nest, merely laying its eggs on a ledge of shale or other rock. Both parents were invariably seen about the spot. In some instances the eggs found were much larger than in others.

Mr. Dall mentions shooting a pair near Nuk´koh, on the Yukon River, that had a nest on a dead spruce. The young, on the 1st of June, were nearly ready to fly. It was not a common species, but was found from Nulato to Sitka and Kodiak.

In regard to general characteristics of this Falcon, they do not apparently differ in any essential respects from those of the better-known Falco communis of the Old World. It flies with immense rapidity, rarely sails in the manner of other Hawks, and then only for brief periods and when disappointed in some attempt upon its prey. In such cases, Mr. Audubon states, it merely rises in a broad spiral circuit, in order to reconnoitre a space below. It then flies swiftly off in quest of plunder. These flights are made in the manner of the Wild Pigeon. When it perceives its object, it increases the flappings of its wings, and pursues its victim with a surprising rapidity. It turns, and winds, and follows every change of motion of the object of pursuit with instantaneous quickness. Occasionally it seizes a bird too heavy to be managed, and if this be over the water it drops it, if the distance to land be too great, and flies off in pursuit of another. Mr. Audubon has known one of this species to come at the report of a gun, and carry off a Teal not thirty steps distant from the sportsman who had killed it. This daring conduct is a characteristic trait.

This bird is noted for its predatory attacks upon water-fowl, but it does not confine itself to such prey. In the interior, Richardson states that it preys upon the Wild Pigeon, and upon smaller birds. In one instance Audubon has known one to follow a tame Pigeon to its house, entering it at one hole and instantly flying out at the other. The same writer states that he has seen this bird feeding on dead fish that had floated to the banks of the Mississippi. Occasionally it alights on the dead branch of a tree in the neighborhood of marshy ground, and watches, apparently surveying, piece by piece, every portion of the territory. As soon as it perceives a suitable victim, it darts upon it like an arrow. While feeding, it is said to be very cleanly, tearing the flesh, after removing the feathers, into small pieces, and swallowing them one by one.

The European species, as is well known, was once largely trained for the chase, and even to this day is occasionally used for this purpose; its docility in confinement, and its wonderful powers of flight, rendering it an efficient assistant to the huntsman. We have no reason to doubt that our own bird might be made equally serviceable.

Excepting during the breeding-season, it is a solitary bird. It mates early in February, and even earlier in the winter. Early in the fall the families separate, and each bird seems to keep to itself until the period of reproduction returns.

In confinement, birds of this family become quite tame, can be trained to habits of wonderful docility and obedience, and evince even an affection for the one who cares for their wants.

This species appears to nest almost exclusively on cliffs, and rarely, if ever, to make any nests in other situations. In a few rare and exceptional cases this Falcon has been known to construct a nest in trees. Mr. Ord speaks of its thus nesting among the cedar swamps of New Jersey; but this fact has been discredited, and there has been no recent evidence of its thus breeding in that State. Mr. Dall found its nest in a tree in Alaska, but makes no mention of its peculiarities.

The eggs of this species are of a rounded-oval shape, and range from 2.00 to 2.22 inches in length, and from 1.60 to 1.90 in width. Five eggs, from Anderson River, have an average size of 2.09 by 1.65 inches. An egg from Mount Tom, Mass., is larger than any other I have seen, measuring 2.22 inches in length by 1.70 in breadth, and differs in the brighter coloring and a larger proportion of red in its markings. The ground is a deep cream-color, but is rarely visible, being generally so entirely overlaid by markings as nowhere to appear. In many the ground-color appears to have a reddish tinge, probably due to the brown markings which so nearly conceal it. In others, nothing appears but a deep coating of dark ferruginous or chocolate-brown, not homogeneous, but of varying depth of coloring, and here and there deepening into almost blackness. In one egg, from Anderson River, the cream-colored ground is very apparent, and only sparingly marked with blotches of a light brown, with a shading of bronze. An egg from the cabinet of Mr. Dickinson, of Springfield, taken on Mount Tom, Massachusetts, is boldly blotched with markings of a bright chestnut-brown, varying greatly in its shadings.

Subgenus ÆSALON, KaupÆsalon, Kaup, 1829. (Type, Falco æsalon, Gmelin, = F. lithofalco, Gm.)

Hypotriorchis, Auct. nec Boie, 1826, the type of which is Falco subbuteo, Linn.

Dendrofalco, Gray, 1840. (Type, F. æsalon, Gmel.)

This subgenus contains, apparently, but the single species F. lithofalco, which is found nearly throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and in different climatic regions is modified into geographical races. Of these, North America possesses three, and Europe one; they may be distinguished as follows:—

Species and RacesF. lithofalco. Second and third quills longest; first usually shorter than, occasionally equal to, or rarely longer than, the fourth. Adult female, and young of both sexes. Above brownish, varying from pale earth-brown, or umber, to nearly black, plain, or with obscure transverse spotting of lighter; tail with five to eight lighter bands, which, however, are sometimes obsolete, except the terminal one. Beneath ochraceous-white, longitudinally striped with brown or dusky over the whole surface. Adult male (except in var. suckleyi and richardsoni?). Above plumbeous-blue, with darker shaft-streaks; tail with more or less distinct bands of black, and paler tip. Beneath much as in the female and young, but stripes usually narrower and more reddish. Wing, 7.20–9.00; tail, 4.90–6.30; culmen, .45–.60; tarsus, 1.30–1.60; middle toe, 1.15–1.51.

a. Adult male plumbeous-blue above; sexes very unlike in adult dress. Female and young without transverse spotting on upper parts.

Adult male. Tail deep plumbeous, tipped with ash, with six transverse series of dusky spots (which do not touch the shaft nor edge of the feathers) anterior to the subterminal zone, the black of which extends forward along the edge of the feather. Inner web of the longest primary with ten transverse spots of white. Streaks on the cheeks enlarged and blended, forming a conspicuous “mustache.” Pectoral markings linear black. The ochraceous wash deepest across the nape and breast, and along the sides, and very pale on the tibiæ. Adult female. Above brownish-plumbeous, the feathers becoming paler toward their margins, and with conspicuous black shaft-streaks. Tail with eight (three concealed) narrow bands of pale fulvous-ashy; longest primary with ten light spots on inner web. Outer webs of primaries with a few spots of ochraceous. Young. Similar to the ♀ adult, but with a more rusty cast to the plumage, and with more or less distinct transverse spots of paler on the upper parts. Wing, 7.60–9.00; tail, 5.10–6.30; culmen, .45–.55; tarsus, 1.35–1.47; middle toe, 1.15–1.35. Hab. Europe … var. lithofalco.58

Adult male. Tail light ash, tipped with white, and crossed by three or four nearly continuous narrow bands of black (extending over both webs, and crossing the shaft), anterior to the broad subterminal zone, the black of which does not run forward along the edge of the feathers. Inner web of longest primary with seven to nine transverse spots of white. Streaks on the cheeks sparse and fine, not condensed into a “mustache.” Pectoral markings broad clear brown. Ochraceous wash weak across the nape and breast, and along sides, and very deep on the tibiæ. Adult female. Above plumbeous-umber, without rusty margins to the feathers, and without conspicuous black shaft-streaks. Tail with only five (one concealed) narrow bands of pale ochraceous; outer webs of primaries without ochraceous spots; inner web of outer primary with eight spots of white. Young. Like the adult female, but darker. Wing, 7.90–8.25; tail, 5.15–5.25; tarsus, 1.00; middle toe, 1.25. Hab. Entire continent of North America; West Indies … var. columbarius.

b. Adult male not bluish? sexes similar? upper parts with lighter transverse spots.

Adult. Above light grayish-umber, or earth-brown, with more or less distinct lighter transverse spots; secondaries crossed by three bands of ochraceous spots, and outer webs of inner primaries usually with spots of the same. Tail invariably with six complete and continuous narrow bands of dull white. Beneath white, with broad longitudinal markings of light brown, these finer and hair-like on the tibiæ and cheeks, where they are sparse and scattered, not forming a “mustache.” Top of the head much lighter than the back. Young. Similar, but much tinged with rusty above, all the white portions inclining to pale ochraceous. Wing, 7.70–9.00; tail, 5.00–6.30; culmen, .50–.60; tarsus, 1.40–1.65; middle toe, 1.20–1.51. Second and third quills longest; first equal to fourth, slightly shorter, or sometimes slightly longer. Hab. Interior plains of North America, between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, from the Arctic regions to Texas … var. (?) richardsoni.

c. Adult male not bluish? sexes similar? upper parts without transverse spots, and tail without lighter bands, except at the tip.

Above plain brownish-black; the tail narrowly tipped with whitish, but without other markings; inner webs of the primaries without lighter spots. Beneath pale ochraceous broadly striped with sooty-black. Wing, 7.35–8.50; tail, 5.25–5.75; culmen, .50–.55; tarsus, 1.30–1.62; middle toe, 1.25–1.35. Hab. Northwest coast region from Oregon to Sitka … var. suckleyi.