полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

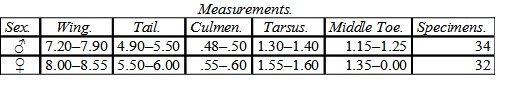

Adult female. Pattern of coloration as in the male, but the colors different. The blue above replaced by dark umber-brown with a plumbeous cast, and showing more or less distinct darker shaft-lines; these on the head above very broad, giving a streaked appearance; white spots on inner webs of primaries more ochraceous than in the male. Tail dark plumbeous-brown, shading into blackish toward end, with five rather narrow ochraceous or soiled white bars, the first of which is concealed by the upper coverts, the last terminal. White beneath, less tinged with reddish than in the male, the tibiæ not different from the other portions; markings beneath as in the male.

Juv. Above plumbeous-brown, tinged with fulvous on head, and more or less washed with the same on the rump; frequently the feathers of the back, rump, scapulars, and wings pass into a reddish tinge at the edge; this color is, however, always prevalent on the head, which is conspicuously streaked with dusky. Tail plumbeous-dusky, darker terminally, with five regular light bars, those toward the base ashy, as they approach the end becoming more ochraceous; these bars are more continuous and regular than in the adult female, and are even conspicuous on the middle feathers. Primaries dusky, passing on edge (terminally) into lighter; spots on the inner webs broader than in the female, and pinkish-ochre; outer webs with less conspicuous corresponding spots of the same. Beneath soft ochraceous; spots as in adult female, but less sharply defined; tibiæ not darker than abdomen.

Hab. Entire continent of North America, south to Venezuela and Ecuador; West India Islands.

Localities: Ecuador (high regions in winter, Scl. P. Z. S. 1858, 451); Cuba (Cab. Jour. II, lxxxiii, Gundlach, Sept. 1865, 225); Tobago (Jard. Ann. Mag. 116); S. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 323, breeding?); W. Arizona (Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 42); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 134); Venezuela (Scl. & Salv. 1869, 252).

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 42; Boston Society, 11; Philadelphia Academy, 10; Museum Comp. Zoöl., 7; New York Museum, 3; G. N. Lawrence, 2; R. Ridgway, 4. Total, 79.

The plumage of the adult male, which is not as often seen as that of the younger stages and adult female, is represented in the Smithsonian Collection by fifteen specimens, from various parts of North America. Of these, an example from Jamaica exhibits the purest shades of color, though agreeing closely with some specimens from the interior of the United States; the cinereous above being very fine, and of a light bluish cast. The upper tail-coverts are tipped with white; the tail is a quarter of an inch longer than in any North American specimen, one half-inch longer than the average; the wing, however, is about the same.

A specimen from Santa Clara, California (4,475, Dr. J. G. Cooper), like most of those from the Pacific coast, has the cinereous very dark above, while beneath the ochraceous is everywhere prevalent; the flanks are strongly tinged with blue; the black bars of the tail are much broken and irregular. A specimen from Jamaica (24,309, Spanish Town; W. T. March), however, is even darker than this one, the stripes beneath being almost pure black; on the tail black prevails, although the bands are very regular. Nos. 27,061, Fort Good Hope, British America, 43,136, Fort Yukon, Alaska, and 51,305, Mazatlan, Mexico, have the streaks beneath narrow and linear; the ochraceous confined to the tibiæ, which are of a deep shade of this color.

Falco columbarius.

A specimen from Nicaragua (No. 40,957, Chinandega) is like North American examples, but the reddish tinge beneath is scarcely discernible, and confined to the tibiæ, which are but faintly ochraceous; the markings beneath are broad and deep umber, the black shaft-streak distinct.

In the adult female there is as little variation as in the male in plumage, the shade of brown above varying slightly, also the yellowish tinge beneath; the bars on the tail differ in continuity and tint in various specimens, although they are always five in number,—the first concealed by the coverts, the last terminal. In 19,382, Fort Simpson, British America, and 2,706, Yukon, R. Am. (probably very old birds), the light bars are continuous and pale dull ashy.

The young vary about the same as adults. Nos. 19,381, Big Island, Great Slave Lake; 5,483, Petaluma, California; and 3,760, Racine, Wisconsin,—are young males moulting, scattered feathers appearing on the upper parts indicating the future blue plumage.

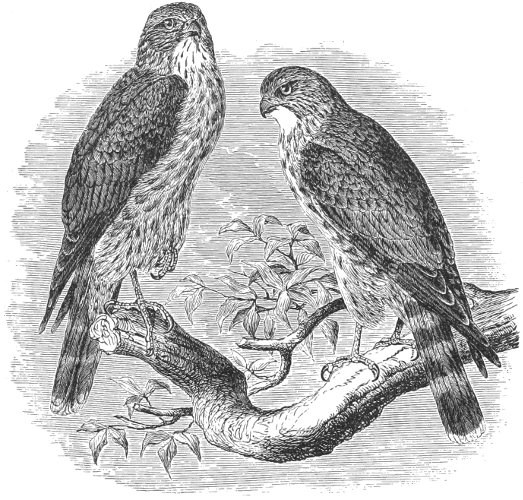

Var. suckleyi, RidgwayBLACK MERLINSp. Char. A miniature of F. peregrinus, var. pealei. Above, uniform fuliginous-black, the secondaries and tail-feathers very narrowly but sharply tipped with white, and the primaries passing into whitish on their terminal margin; nuchal region with concealed spotting of pale rusty or dingy whitish. Beneath, longitudinally striped with fuliginous-black, or dark sooty-brown, and pale ochraceous; the former predominating on the breast, the latter prevailing on the throat and anal region. Sides and flanks nearly uniform dusky, with roundish white spots on both webs; lower tail-coverts with a broad sagittate spot of dusky on each feather. Lining of the wing fuliginous-dusky, with sparse, small roundish spots of white. Inner webs of primaries plain dusky, without spots, or else with them only faintly indicated. Tail plain dusky-black, narrowly tipped with white, and without any bands, or else with them only faintly indicated.

Male (No. 4,477, Shoalwater Bay, Washington Territory; J. G. Cooper). Wing, 7.35; tail, 5.25; culmen, .50; tarsus, 1.30; middle toe, 1.25.

Female (No. 5,832, Fort Steilacoom, Washington Territory, September, 1856; Dr. George Suckley). Wing, 8.50; tail, 5.70; culmen, .55; tarsus, 1.62; middle toe, 1.35.

Hab. Coast region of Northern California, Oregon, and Washington Territory (probably northward to Alaska). Puget Sound, Steilacoom, Yreka, California (Oct.), and Shoalwater Bay (National Museum).

The plumage of this race is the chief point wherein it differs from the other forms of the species; and in its peculiarities we find just what should be expected from the Oregon region, merely representing as it does the melanistic condition so frequently observable in birds from the northwest coast.

The upper parts are unicolored, being continuous blackish-plumbeous from head to tail. The tail is tipped with white, but the bars are very faintly indicated, being in No. 4,499 altogether wanting, while in 21,333 they can scarcely be discovered, and only four are indicated; in the others there is the usual number, but they are very obsolete. In No. 4,499, the most extreme example, the spots on the inner webs of the primaries are also wanting; the sides of the head are very thickly streaked, the black predominating, leaving the superciliary stripe ill-defined; the throat is streaked, and the other dark markings beneath are so exaggerated that they cover all portions, and give the prevailing color; the under tail-coverts have broad central cordate black spots.

Another specimen from this region (4,476, Puget Sound) is similar, but the spots on primaries are conspicuous, as in examples of the typical style; indeed, except in the most extreme cases, these spots will always be found indicated, leading us to the unavoidable conclusion that the specimens in question represent merely the fuliginous condition of the common species; not the condition of melanism, but the peculiar darkened plumage characteristic of many birds of the northwest coast, the habitat of the present bird; it should then be considered as rather a geographical race, co-equal to the Falco gyrfalco, var. labradora, F. peregrinus, var. pealei, and other forms, and not confounded with the individual condition of melanism, as seen in certain species of Buteones.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 6.

Second quill longest; first quill equal to, a little shorter than, or a little longer than, the fourth.

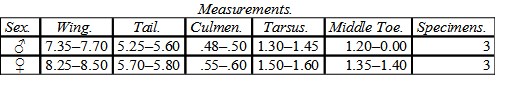

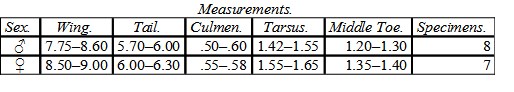

Var. richardsoni, RidgwayRICHARDSON’S MERLINFalco æsalon, Rich. & Swains. F. B. A. II, pl. xxv, 1831.—Nutt. Man. Orn. II, 558.—Coues, P. A. N. S. Philad. 1866, p. 42 (in text). Falco (Hypotriorchis) richardsoni, Ridgway, P. A. N. S. Philad. Dec. 1870, 145. Falco richardsoni, Coues, Key, 1872, p. 214.

Sp. Char. Adult male like the female and young? The known stages of plumage more like the adult female and young of var. lithofalco (F. æsalon, Auct.) than like var. columbarius.

Adult male (Smithsonian, No. 5,171, mouth of the Vermilion River, near the Missouri, October 25, 1856; Lieutenant Warren, Dr. Hayden). Upper plumage dull earth-brown, each feather grayish-umber centrally, and with a conspicuous black shaft-line. Head above approaching ashy-white anteriorly, the black shaft-streaks being very conspicuous. Secondaries, primary coverts, and primaries margined terminally with dull white; the primary coverts with two transverse series of pale ochraceous spots; outer webs of primaries with spots of the same, corresponding with those on the inner webs. Upper tail-coverts tipped, and spotted beneath the surface, with white. Tail clear drab, much lighter than the primaries, but growing darker terminally, having basally a slightly ashy cast; crossed with six sharply defined, perfectly continuous bands (the last terminal) of ashy-white. Head, frontally, laterally, and beneath,—a collar around the nape (interrupting the brown above),—and the entire lower parts, white, somewhat ochraceous, this most perceptible on the tibiæ; cheeks and ear-coverts with sparse, fine hair-like streaks of black; nuchal collar, jugulum, breast, abdomen, sides, and flanks with a medial linear stripe of clear ochre-brown on each feather; these stripes broadest on the flanks; each stripe with a conspicuously black shaft-streak; tibiæ and lower tail-coverts with fine shaft-streaks of brown, like the broader stripes of the other portions. Chin and throat, only, immaculate. Lining of the wing spotted with ochraceous-white and brown, in about equal amount, the former in spots approaching the shaft. Inner webs of primaries with transverse broad bars of pale ochraceous,—eight on the longest. Wing-formula, 2, 3–4, 1. Wing, 7.70; tail, 5.00; culmen, .50; tarsus, 1.30; middle toe, 1.25; outer, .85; inner, .70; posterior, .50.

Adult female (58,983, Berthoud’s Pass, Rocky Mountains, Colorado Territory; Dr. F. V. Hayden, James Stevenson). Differing in coloration from the male only in the points of detail. Ground-color of the upper parts clear grayish-drab, the feathers with conspicuously black shafts; all the feathers with pairs of rather indistinct rounded ochraceous spots, these most conspicuous on the wings and scapulars. Secondaries crossed with three bands of deeper, more reddish ochraceous. Bands of the tail pure white. In other respects exactly as in the male. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–1. Wing, 9.00; tail, 6.10; culmen, .55; tarsus, 1.40; middle toe, 1.51.

Young male (40,516, Fort Rice, Dacotah, July 20, 1865; Brig.-Gen. Alfred Sully, U. S. A., S. M. Rothammer). Differing from the adult only in minute details. Upper surface with the rusty borders of the feathers more washed over the general surface; the rusty-ochraceous forms the ground-color of the head,—paler anteriorly, where the black shaft-streaks are very conspicuous; spots on the primary coverts and primaries deep reddish-ochraceous; tail-bands broader than in the adult, and more reddish; the terminal one twice as broad as the rest (.40 of an inch), and almost cream-color in tint. Beneath pale ochraceous, this deepest on the breast and sides; markings as in the adult, but anal region and lower tail-coverts immaculate; the shaft-streaks on the tibiæ, also, scarcely discernible. Wing, 7.00; tail, 4.60.

Hab. Interior regions of North America, between the Mississippi Valley and the Rocky Mountains, from Texas to the Arctic regions.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 10; Museum Comp. Zoöl., 2; R. Ridgway, 3. Total, 15.

Since originally describing this bird, I have seen additional examples, and still consider it as an easily recognized race, not at all difficult to distinguish from columbarius. Now, however, I incline strongly to the theory that it represents merely the light form of the central prairie regions, of the common species; since its characters seem to be so analogous to those of the races of Buteo borealis and Bubo virginianus of the same country. It is doubtful whether some very light-colored adult males, supposed to belong to columbarius, as restricted, should not in reality be referred to this race, as the adult plumage of the male. But having seen no adult males from the region inhabited by the present bird obtained in the breeding-season, I am still in doubt whether the present form ever assumes the blue plumage.

As regards the climatic or regional modifications experienced by the Falco lithofalco on the American continent, the following summary of facts expresses my present views upon the subject. First: examples identical in all respects, or at least presenting no variations beyond those of an individual character, may be found from very widely separated localities; but the theory of explanation is, that individuals of one race may become scattered during their migrations, or wander off from their breeding-places. Second: the Atlantic region, the region of the plains, and the region of the northwest coast, have each a peculiar race, characterized by features which are also distinctive of races of other birds of the same region, namely, very dark—the dark tints intensified, and their area extended—in the northwest coast region; very light—the light markings extended and multiplied—in the middle region; and intermediate in the Atlantic region.

Habits. The distribution of the well-known Pigeon Hawk is very nearly coextensive with the whole of North America. It is found in the breeding-season as far to the north as Fort Anderson, on the Anderson and McKenzie rivers, ranging even to the Arctic coast. Specimens were taken by Mr. Ross at Lapierre House and at Fort Good Hope. Several specimens were taken by Mr. Dall at Nulato, where, he states, it is found all the year round. They were also taken by Bischoff at Kodiak. During the breeding-season it is found as far south as Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the northern portions of Maine, and probably Vermont and New York. It is abundant on the Pacific coast.

In the winter months it is to be met with throughout the more temperate portions of North America, in Mexico, Central America, and Northern South America. Dr. Woodhouse mentions finding this species very abundant especially among the wooded banks of watercourses throughout Texas, New Mexico, and the Indian Territory.

Mr. March states that this Hawk is a permanent resident in the island of Jamaica, more frequently found among the hills than on the plains, and has been known to breed there. It is a visitant of Cuba. Dr. Cooper thinks they are not very common in Washington Territory, though, as they are found there throughout the summer, they undoubtedly breed there. In August, 1855, Dr. Cooper shot one of a small family of young that had but recently left their nest. They migrate southward in winter, and are abundant in California in October and November.

Dr. Suckley found them abundant about Fort Steilacoom early in August. Near Puget Sound this species is thought to breed in the recesses of the Cascade Mountains, only coming down upon the open plains late in the summer. Dr. Newberry found it paired and nesting about the Klamath Lakes, and states that it also occupies all the region south of the Columbia, in Oregon. Mr. Dresser states that he found this Falcon common about Bexar and the adjoining counties during the entire year, and that they occasionally breed near the Medina River. I have been unable to find any satisfactory evidence that this Hawk ever breeds in any part of Massachusetts, or anywhere south of the 44th parallel in the Eastern States, except, perhaps, in mountainous regions.

This Hawk is remarkable for its rapid flight, and its courage and its enterprise in attacking birds as large as or even larger than itself, though generally it only preys upon smaller birds, such as Grakles, Red-winged Blackbirds, Robins, and Pigeons. Dr. Cooper states that having been attracted by an unusual screaming of some bird close to the house, he was surprised to find that one of these Hawks had just seized upon a Flicker, a bird as large as itself, the weight of which had brought it to the ground, and which it continued to hold in its claws even after it had been mortally wounded. Dr. Heermann once found one of these birds just preparing to feed on a large and plump California Partridge.

In Tamaulipas, Mexico, where Lieutenant Couch found it quite common, he speaks of it as being very quiet, flying but little, and generally watching for its quarry from the limb of a dry tree. Mr. Audubon makes no mention of any peculiarities of habits. Mr. Nuttall was evidently unfamiliar with it, stating it to be unknown in New England, and a resident of the Southern States only.

In Nova Scotia, Mr. Downes speaks of it as common, breeding in all the wooded parts of the country. It is said to be not troublesome to the farmer, but to feed upon the smaller birds. He mentions that once, on his voyage to Boston, one of these birds flew aboard and allowed itself to be captured, and was kept alive and fed readily, but soon after escaped.

Mr. B. R. Ross, in his notes on the birds and nests obtained by him in the country about Fort Resolution, Lapierre House, and Good Hope, mentions this bird as the most common of the true Falcons in that district, where it ranges to the Arctic coast. Its nest is said to be composed of sticks, grass, and moss, and to be built generally in a thick tree, at no great elevation. The eggs, he adds, are from five to seven in number, 1.60 inches in length by 1.20 in breadth. Their ground-color he describes as a light reddish-buff, clouded with deep chocolate and reddish-brown blotches, more thickly spread at the larger end of the egg, where the under tint is almost entirely concealed by them. This description is given from three eggs procured with their parent at Fort Resolution.

From Mr. MacFarlane’s notes, made from his observations in the Anderson River country, we gather that one nest was found on the ledge of a cliff of shaly mud on the banks of the Anderson River; another nest was on a pine-tree, eight or nine feet from the ground, and composed of a few dry willow-twigs and some half-decayed hay, etc. It was within two hundred yards of the river-bank. A third nest was in the midst of a small bushy branch of a pine-tree, and was ten feet from the ground. It was composed of coarse hay, lined with some of a finer quality, but was far from being well arranged. Mr. MacFarlane was confident that it had never been used before by a Crow or by any other bird. The oviduct of the female contained an egg ready to be laid. It was colored like the others, but the shell was still soft, and adhered to the fingers on being touched. In another instance the eggs were found on a ledge of shale in a cliff on the bank, without anything under them in the way of lining. He adds that they are even more abundant along the banks of the McKenzie than on the Anderson River.

Mr. MacFarlane narrates that on the 25th of May an Indian in his employ found a nest placed in the midst of a pine branch, six feet from the ground, loosely made of a few dry sticks and a small quantity of coarse hay. It then contained two eggs. Both parents were seen, but when fired at were missed. On the 31st he revisited the nest, which still contained only two eggs, and again missed the birds. He again went to the nest, several days after, to secure the parents, and was much surprised to find that the eggs were gone. His first supposition was that some other person had taken them, but, after looking carefully about, he perceived both birds at a short distance; and this caused him to institute a search, which soon resulted in his finding that the eggs had been removed by them to the face of a muddy bank at least forty yards distant from the original nest. A few decayed leaves had been placed under them, but nothing else in the way of protection. A third egg had been added since his previous examination. These facts Mr. MacFarlane carefully investigated, and vouches for their entire accuracy.

Another nest, containing four eggs, was on the ledge of a shaly cliff, and was composed of a very few decayed leaves placed under the eggs.

Mr. R. Kennicott found a nest, June 2, 1860, in which incubation had already commenced. It was about a foot in diameter, was built against the trunk of a poplar, and its base was composed of sticks, the upper parts consisting of mosses and fragments of bark.

Mr. Audubon mentions finding three nests of this bird in Labrador, in each of which there were five eggs. These nests were placed on the top branches of the low firs peculiar to that country, composed of sticks, and slightly lined with moss and a few feathers. He describes the eggs as 1.75 inches long, and 1.25 broad, with a dull yellowish-brown ground-color, thickly clouded with irregular blotches of dark reddish-brown. One was found in the beginning of July, just ready to hatch. The young are at first covered with a yellowish down. The old birds are said to evince great concern respecting their eggs or young, remaining about them and manifesting all the tokens of anger and vexation of the most courageous species. A nest of this Hawk (S. I. 7,127) was taken at St. Stephen, N. B., by Mr. W. F. Hall; and another (S. I. 15,546) in the Wahsatch Mountains, by Mr. Ricksecker. The latter possibly belonged to the var. richardsoni.

The nest of this bird found in Jamaica by Mr. March was constructed on a lofty tree, screened by thick foliage, and was a mere platform of sticks and grass, matted with soft materials, such as leaves and grasses. It contained four eggs, described as “round-oval or spherical” in shape, measuring “1.38 by 1.13 inches, of a dull clayish-white, marked with sepia and burnt umber, confluent dashes and splashes, irregularly distributed, principally about the middle and the larger end.” Four others, taken from a nest in the St. Johns Mountains, were oblong-oval, about the same size and nearly covered with chocolate and umber blotches. Mr. March thinks they belong to different species.

Mr. Hutchins, in his notes on the birds of Hudson’s Bay, states that this species nests on rocks or in hollow trees; that the nest consists of sticks and grass, lined with feathers; and describes the eggs as white, thinly marked with red spots. In the oviduct of a Hawk which Dr. Richardson gives as Falco æsalon, were found “several full-sized white eggs, clouded at one end by a few bronze-colored spots.” A nest was found by Mr. Cheney at Grand Menan, from which he shot what he presumed to be the parent bird of this species. Its four eggs agreed with the descriptions given by Hutchins and Richardson much more nearly than with the eggs of this species. The eggs found by Mr. Cheney may have been very small eggs of A. cooperi, in which case the presence of the columbarius on the nest cannot be so easily explained.

Three eggs, two from Anderson River and one from Great Slave Lake, range from 1.53 to 1.60 inches in length, and from 1.20 to 1.22 in breadth, their average measurements being 1.56 by 1.21. They have a ground-color of a rich reddish-cream, very generally covered with blotches and finer markings of reddish-brown, deepening in places almost into blackness, and varying greatly in the depth of its shading, with a few lines of black. In one the red-brown is largely replaced by very fine markings of a yellowish sepia-brown, so generally diffused as to conceal the ground and give to it the appearance of a light buff. Mr. Ridgway, after a careful analysis of the varying markings and sizes of twenty-one eggs, has kindly given the following:—