полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

A History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Its nest and eggs were taken in Utah by Mr. Ricksecker. I have no notes in regard to the former. A finely marked specimen of one of the eggs procured by him is in my cabinet. It measures 2.15 inches in length by 1.65 in breadth. It is of a somewhat less rounded-oval shape than are the eggs of the anatum. The ground-color is a rich cream, with a slightly pinkish tinge, and is beautifully marked with blotches of various sizes, shapes, and shades of a red-brown tinged with chestnut, and with occasional shadings of purplish. These are confluent about one end, which in the specimen before me chances to be the smaller one. It very closely resembles the eggs of the European F. lanarius.

An egg in the Smithsonian Collection (15,596), taken at Gilmer, Wyoming Territory, May 13, 1870, by Mr. H. R. Durkee, has a ground-color of pinkish-white, varying in two eggs to diluted vinaceous, thickly spotted and minutely freckled with a single shade of a purplish-rufous. In shape they are nearly elliptical, the smaller end being scarcely more pointed than the larger. They measure 2.27 by 1.60 to 1.65 inches. The nest was built on the edge of a cliff. Its eggs were also taken by Dr. Hayden while with Captain Raynolds, at Gros Vent Fork, June 8, 1860.

Subgenus FALCO, MœhringFalco, Mœhring, 1752. (Type, Falco peregrinus, Gm. = F. communis, Gm.)

Rhynchodon, Nitzsch, 1840. (In part only.)

Euhierax, Webb. & Berth., 1844. (Type, Falco—?)

Icthierax, Kaup, 1844. (Type, Falco frontalis, Daud.)

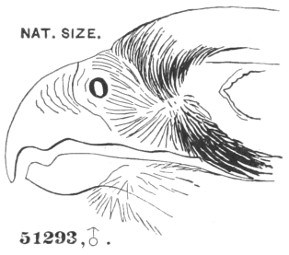

51293, ♂. ¼

F. aurantius.

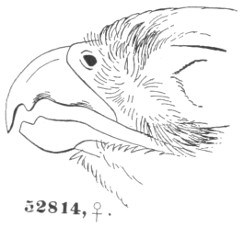

52814, ♀.

F. rufigularis (nat. size).

51293, ♂. ½

F. aurantius.

51293, ♂. nat. size.

F. aurantius.

52814, ♀.

F. rufigularis (nat. size).

The following synopsis of the three American species of this subgenus may serve to distinguish them from each other, though only two of them (F. aurantius and F. rufigularis) are very closely related. The comparative characters of the several geographical races of the other one (F. communis), which is cosmopolitan in its habitat, being included under the head of that species, may explain the reasons why they are separated from each other.

Species and RacesA. First and second quills equal and longest; first with inner web emarginated, second with inner web slightly sinuated. Young with longitudinal stripes on the lower parts. Adult and young stages very different.

1. F. communis. Wing, 11.50–14.30; tail, 7.00–8.50; culmen, .72–.95; tarsus, 1.65–2.20; middle toe, 1.80–2.30.52 Second quill longest; first shorter than, equal to, or longer than third. Adult. Above plumbeous, darker anteriorly, lighter and more bluish posteriorly; anteriorly plain, posteriorly with darker transverse bars, these growing more sharply defined towards the tail. Beneath ochraceous-white, varying in tint from nearly pure white to deep ochraceous, those portions posterior to the jugulum transversely barred, more or less, with blackish or dark plumbeous; anterior lower parts (from the breast forward) without transverse bars. Young. No transverse bars on the body, above or below. Above blackish-brown, varying to black, the feathers usually bordered terminally with ochraceous or rusty; forehead usually more or less washed with the same. Beneath ochraceous, varying in shade; the whole surface with longitudinal stripes of blackish. Inner webs of tail-feathers and primaries with numerous transverse elliptical spots of ochraceous. Hab. Cosmopolitan.

a. Young dark brown above, the feathers bordered with rusty or whitish. Beneath white or ochraceous, with narrow longitudinal stripes of dusky. Inner webs of tail-feathers with transverse bars.

Auriculars white, cutting off the black of the cheeks with a prominent “mustache.”

Beneath pure white, the breast and middle of the abdomen without markings. Wing, 12.75; tail, 7.30; culmen, .80; tarsus, 2.00; middle toe, 1.80. Hab. Eastern Asia … var. orientalist.53

Beneath pale ochraceous, the breast always with longitudinal dashes, or elliptical spots, of dusky; middle of abdomen barred. Wing, 11.50–14.30; tail, 7.00–8.50; culmen, .72–.95; tarsus, 1.65–2.20; middle toe, 1.80–2.30. Hab. Europe … var. communis.54

Beneath varying from deep ochraceous to nearly pure white, the breast never with distinct longitudinal or other spots, usually with none at all. Middle of abdomen barred, or not. Wing, 11.30–14.75; tail, 6.00–9.00; culmen, .75–1.00; tarsus, 1.60–2.10; middle toe, 1.75–2.20. Hab. America (entire continent) … var. anatum.

Auriculars black, nearly, or quite, as far down as the lower end of the “mustache.”

Beneath varying from deep ochraceous to white, the breast streaked or not. Lower parts more uniformly and heavily barred than in the other races. Young with narrower streaks beneath. Wing, 11.15–12.60; tail, 6.11–8.00; culmen, .81–.90; tarsus, 1.60–2.05; middle toe, 1.75–2.15. Hab. Australia … var. melanogenys.55

b. Young unvariegated brownish-black above. Beneath brownish-black, faintly streaked with white, or nearly unvariegated. Inner webs of tail-feathers without transverse bars.

Wing, 14.90–15.09; tail, 8.50; culmen, .95–1.00; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 2.15–2.21. Hab. Northwest coast of North America, from Oregon to Sitka … var. pealei.

B. Second quill longest; first with inner web emarginated, the second with inner web not sinuated. Young without longitudinal stripes on lower parts. Adult and young stages hardly appreciably different.

Above plumbeous or black; beneath black from the jugulum to the tibiæ, with transverse bars of white, ochraceous, or rufous; throat and jugulum white, white and rufous, or wholly ochraceous, with a semicircular outline posteriorly; tibiæ, anal region, and crissum uniform deep rufous, or spotted with black on an ochraceous or a white and rufous ground. Adult. Plumbeous above, the feathers darker centrally, and with obscure darker bars posteriorly; jugulum immaculate. Young. Black above, the feathers bordered terminally with rusty, or else dark plumbeous without transverse bars; jugulum with longitudinal streaks.

2. F aurantius.56 Wing, 9.50–12.00; tail, 5.40–6.25; culmen, .96; tarsus, 1.50–1.60; middle toe, 1.75–2.10. Second quill longest; first longer than third. Crissum ochraceous, or white and rufous, with large transverse spots of black; upper tail-coverts sharply barred with pure white or pale ash. Adult. Above plumbeous-black, the feathers conspicuously bordered with plumbeous-blue. Throat and jugulum immaculate; white centrally and anteriorly, deep rufous laterally and posteriorly. Tibiæ plain rufous. Young. Above uniform dull black, the feathers sometimes bordered inconspicuously with rusty. Throat and jugulum varying from white to ochraceous or rufous (this always deepest laterally and posteriorly). Tibiæ sometimes thickly spotted transversely with black. Hab. Tropical America, north to Southern Mexico.

3. F. rufigularis.57 Wing, 7.20–9.00 (♂, wing, 7.70; tail, 3.95–5.50; culmen, .45–.58; tarsus, 1.20–1.55; middle toe, 1.15–1.40). Second quill longest; first longer than third. Crissum uniform deep reddish-rufous, rarely barred with white and dusky. Upper tail-coverts obsoletely barred with plumbeous.

Adult. Above plumbeous-black, the feathers lightening into plumbeous-blue on the edges and ends, and showing obscure bars on the posterior portions. Throat and jugulum ochraceous-white, the ochraceous tinge deepest posteriorly and without any streaks. Young. Above plumbeous-black, without lighter obscure bars, or with a brownish cast, and with faint rusty edges to the feathers. Throat and jugulum deep soft ochraceous, deepest laterally, the posterior portion usually with a few longitudinal streaks of dusky. Hab. Tropical America, north to Middle Mexico.

Falco communis, GmelVar. anatum, BonapAMERICAN PEREGRINE FALCON; DUCK HAWK? Accipiter falco maculatus, Briss. Orn. I, 329. ? Falco nævius, Gmel. S. N. 1789, 271. Falco communis ζ, and F. communis η, Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 31. Falco communis, Coues, Key, 1872, 213, f. 141. Falco peregrinus, Ord. Wils. Am. Orn. 1808, pl. lxvi.—Sab. L. Trans. XII, 529.—Rich. Parry’s 2d Voy. App. 342.—Ib. F. B. A. II, 1831, 23.—Bonap. N. Y. Lyc. II, 27.—Ib. Isis, 1832, 1136; Consp. 1850, 23, No. 4.—King, Voy. Beag. I, 1839, 532.—James. Wils. Am. Orn. 677, Synop. 1852, 683.—Wedderb. Jard. Contr. to Orn. 1849, 81.—Woodh. Sitgr. Zuñi, 1853, 60.—Giraud, B. Long Island, 1844, 14.—Peale, U. S. Ex. Ex. 1848, 66.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. 1841, 51. Falco anatum, Bonap. Eur. & N. Am. B. 1838, 4.—Ib. Rev. Zoöl. 1850, 484.—Bridg. Proc. Zoöl. Soc. pl. xi, 109.—Ib. Ann. N. H. XIII, 499.—Gosse, B. Jam. 1847, 16.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. 1854, 86.—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, 7.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 13, pl. iii, f. 8.—Nutt. Man. 1833, 53.—Peab. B. Mass. 1841, 83.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 1855, 83.—Blakist. Ibis, III, 1861, 315.—March, Pr. Ac. N. S. 1863, 304. Falco nigriceps, Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. I, 1853, 87.—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, 8.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 85.—Coop. & Suckl. P. R. R. Rep’t, VII, ii, 1860, 142.—Gray, Hand List, I, 1869, 19, No. 166.—Sharpe, Ann. & Mag. N. H. Falco orientalis, (Gm.) Gray, Hand List, I, 1869, 19, No. 165 (in part). ? Falco cassini, Sharpe, Ann. & Mag. N. H.

Sp. Char. Adult (♂, 43,134, Fort Resolution, Brit. N. Am., June; J. Lockhart). Upper parts dark bluish-plumbeous, approaching black anteriorly, but on rump and upper tail-coverts becoming fine bluish plumbeous-ash. On the head and neck the continuous plumbeous-black covers all the former except the chin and throat, and the back portion of the latter; an invasion or indentation of the white of lower parts up behind the ear-coverts separating that of the cheeks from the posterior black, throwing the former into a prominent angular patch; forehead and lores grayish. All the feathers above (posterior to the nape) with transverse bars of plumbeous-black, these most sharply defined posteriorly, where the plumbeous is lightest. Tail black, more plumbeous basally, very faintly paler at the tip, and showing ten or eleven transverse narrow bands of plumbeous, these most distinct anteriorly; the bars are clearest on inner webs. Alula, primary and secondary coverts, secondaries and primaries, uniform plumbeous-black, narrowly whitish on terminal margin, most observable on secondaries and inner primaries. Lower parts white, tinged with delicate cream-color, this deepest on the abdomen; sides and tibiæ tinged with bluish. Chin, throat, and jugulum immaculate; the breast, however, with faint longitudinal shaft-streaks of black; sides, flanks, and tibiæ distinctly barred transversely with black, about four bars being on each feather; on the lower tail-coverts they are narrower and more distant; on the abdomen the markings are in the form of circular spots; anal region barred transversely. Lining of the wing (including all the under coverts) white tinged with blue, and barred like the sides; under surface of primaries slaty, with elliptical spots or bars of creamy-white on inner webs, twelve on the longest. Wing-formula, 2–1–3. Wing, 12.25; tail, 6.00; tarsus, 1.60; middle toe, 1.85; outer, 1.40; inner, 1.20; posterior, .80; culmen, .80.

♀ (13,077, Liberty Co., Georgia; Professor J. L. Leconte). Like the male, but ochraceous tinge beneath deeper; no ashy wash; bands on the tail more sharply defined, about ten dark ones being indicated; outer surface of primaries and secondaries with bands apparent; tail distinctly tipped with ochraceous-white. Inner web of longest primary with thirteen, more reddish, transverse spots. White of neck extending obliquely upward and forward toward the eye, giving the black cheek-patch more prominence. Markings beneath as in the male. Wing-formula the same. Wing, 14.50; tail, 7.00; tarsus, 1.95; middle toe, 2.10; culmen, .95.

Juv. (♂, 53,193, Truckee River, Nevada, July 24, 1867; R. Ridgway: first plumage). Above plumbeous-black, tail more slaty. Every feather broadly bordered terminally with dull cinnamon; these crescentic bars becoming gradually broader posteriorly, narrower and more obsolete on the head above. Tail distinctly tipped with pale cinnamon, the inner webs of feathers with obsolete transverse spots of the same, these touching neither the edge nor the shaft; scarcely apparent indications of corresponding spots on outer webs. Region round the eye, and broad “mustache” across the cheeks, pure black, the latter more conspicuous than in the older stages, being cut off posteriorly by the extension of the cream-color of the neck nearly to the eye. A broad stripe of pale ochraceous running from above the ear-coverts back to the occiput, where the two of opposite sides nearly meet. Lower parts purplish cream-color, or rosy ochraceous-white, deepest posteriorly; jugulum, breast, sides, flanks, and tibiæ with longitudinal stripes of plumbeous-black, these broadest on flanks and abdomen, and somewhat sagittate on the tibiæ; lower tail-coverts with distant transverse bars. Lining of the wing like the sides, but the markings more transverse; inner web of longest primary with nine transverse purplish-ochre spots. Wing-formula, 2–1, 3. Wing, 12.50; tail, 7.00. Length, 16.50; expanse, 39.25. Weight, 1½ lbs. Basal half of bill pale bluish-white, cere rather darker; terminal half (rather abruptly) slate-color, the tip deepening into black; iris very dark vivid vandyke-brown; naked orbital space pale bluish-white, with a slight greenish tint; tarsi and toes lemon-yellow, with a slight green cast; claws jet-black.

Hab. Entire continent of America, and neighboring islands.

Localities: Guatemala (Scl. Ibis I, 219); Veragua (Salv. P. Z. S. 1867, 158); Sta. Cruz (Newton, Ibis, I, 63); Trinidad (Taylor, Ibis, 1864, 80); Bahamas (Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1859, VII); Cuba (Cab. Journ. II, lxxxiii); (Gundl. Repert. 1865, 225); Jamaica, (Gosse, B. Jam. 16; March, Pr. Ac. N. S. 1863, 304, et Mus. S. I.); Tierra del Fuego (Sharpe, Ann. & Mag. N. H.; “F. cassini, Sharpe”).

The young plumage above described corresponds exactly with that of young peregrinus from Europe, a comparison of the specimen above described with one of the same age from Germany (54,064, Schlüter Col.) showing no differences that can be expressed. Many American specimens in this plumage (as 19,397, Fort Simpson) show a wash of whitish over the forehead and anterior part of the crown; having before us but the one specimen, we cannot say whether or not this is ever seen in the European bird. Specimens more advanced in season—perhaps in second year—are colored as follows: The black above is more brownish, the feathers margined with pale brown,—these margins broader, and approaching to white, on the upper tail-coverts; the tail shows the ochraceous bars only on inner webs. The supraoral stripe of the youngest plumage is also quite apparent.

A still younger one from the same locality (No. 37,397) has the upper plumage similar to the last, the pale edges to the feathers, however, more distinct; tail with conspicuous spots. White beneath clearer, and invading the dusky of the head above as far back as the middle of the crown; the supraoral stripe is distinct, scarcely interrupted across the nape.

In the adult plumage the principal variation is in the extent and disposition of the bars beneath. In most individuals they are regularly transverse only laterally and posteriorly, those on the belly being somewhat broken into more irregular cordate spots, though always transverse; in no American specimen, however, are they as continuously transverse as in a male (No. 18,804) from Europe, which, however, in this respect, we think, forms an exception to most European examples, at least to those in the Smithsonian Collection. All variations in the form, thickness, and continuity of the markings below, and in the distinctness of the bars above, are individual.

Very old males (as 49,790, Fort Yukon; 27,188, Moose Factory (type of Elliott’s figure of F. peregrinus, in Birds of America); and 42,997, Spanishtown, Jamaica) lack almost entirely the reddish tinge beneath, and have the lateral and posterior portions strongly tinged with blue; the latter feature is especially noticeable in the specimen from Jamaica, in which also the bars are almost utterly wanting medially. Immature birds from this island also lack to a great degree the ochraceous tinge, leaving the whitish everywhere purer.

A female adult European bird differs from the average of North American examples in the conspicuous longitudinal streaks on the jugulum; but in a male these are hardly more distinct than in 13,077, ♀, Liberty Co., Georgia; 11,983, “United States”; 35,456, Peel’s River; 35,449, ♀, and 35,445, ♀, Fort Yukon, Alaska; 35,452, La Pierre’s Hous., H. B. Ter.; 35,459 ♂, Fort Anderson; and 28,099 ♀, Hartford, Conn. In none of these, however, are they so numerous and conspicuous as in a European female from the Schlüter Collection, which, however, differs in these respects only from North American specimens.

A somewhat melanistic individual (in second year? 32,735, Chicago, Ill.; Robert Kennicott) differs as follows: Above continuously pure black; upper tail-coverts and longer scapulars bordered terminally with rusty-whitish. Tail distinctly tipped with white; the inner webs of feathers with eight elliptical transverse bars of pale ochraceous, and indications of corresponding spots of the same on outer webs, forming as many inconspicuous bands. Beneath ochraceous-white; the neck, breast, and abdomen thickly marked with broad longitudinal stripes of clear black,—those on the jugulum cuneate, and on the breast and abdomen broadly sagittate; the tibiæ with numerous cordate spots, and sides marked more transversely; lower tail-coverts with narrow distant transverse bars. On the chin and throat only, the whitish is immaculate, on the other portions being somewhat exceeded in amount by the black. Inner web of longest primary with seven transverse elliptical bars of cream-color. Wing, 12.20; tail, 9.40.

Whether the North American and European Peregrine Falcons are or are not distinct has been a question undecided up to the present day; almost every ornithologist having his own peculiar views upon the relationship of the different forms which have been from time to time characterized. The most favorably received opinion, however, seems to be that there are two species on the American continent, and that one of these, the northern one, is identical with the European bird. Both these views I hold to be entirely erroneous; for after examining and comparing critically a series of more than one hundred specimens of these birds, from every portion of America (except eastern South America), including nearly all the West India Islands, as well as numbers of localities throughout continental North and South America, I find that, with the exception of the melanistic littoral race of the northwest coast (var. pealei), they all fall under one race, which, though itself exceedingly variable, yet possesses characters whereby it may always be distinguished from the Peregrine of all portions of the Old World.

There is such a great amount of variability, in size, colors, and markings, that the F. nigriceps, Cassin, must be entirely ignored as being based upon specimens not distinguishable in any respect from typical anatum. Judging from the characters assigned to the F. cassini by its describer (who evidently had a very small series of American specimens at his command), the latter name must also most probably fall into the list of synonymes of anatum.

Slight as are the characters which separate the Peregrines of the New and Old World, i.e. the immaculate jugulum of the former and the streaked one of the latter, they are yet sufficiently constant to warrant their separation as geographical races of one species; along with which the F. melanogenys, Gould (Australia), F. minor, Bonap. (South Africa), F. orientalis, Gmel. (E. Asia), and F. calidus, Lath. (Southern India and East Indies), must also rank as simple geographical races of the same species. Whether the F. calidus is tenable, I am unable to state, for I have not seen it; but the others appear to be all sufficiently differentiated. The F. radama, Verreaux (Gray’s Hand List, p. 19, No. 170), Mr. Gurney writes me, is the young female of var. minor. Whether the F. peregrinator, Sundevall (Gray’s Hand List, No. 169), is another of the regional forms of F. communis, or a distinct species, I am not able at present to say, not having specimens accessible to me for examination.

Mr. Cassin’s type of “nigriceps” (13,856, ♂, July), from Chile, is before me, and upon comparison with adult males from Arctic America presents no tangible differences beyond its smaller size; the wing is a little more than half an inch, and the middle toe less than the eighth of an inch, shorter than in the smallest of the North American series,—a discrepancy slight indeed, and of little value as the sole specific character; the plumage being almost precisely similar to that of the specimen selected for the type of the description at the head of this article. In order to show the little consequence to be attached to the small size of the individual just mentioned, I would state that there is before me a young bird, received from the National Museum of Chile, and obtained in the vicinity of Santiago, which is precisely similar in plumage to the Nevada specimen described, and in size is even considerably larger, though it is but just to say that it is a female; the wing measures 13.25, instead of 12.50, and the middle toe, 2.00, instead of 1.85. No. 37,336, Tres Marias Islands, Western Mexico,—a young male in second year,—has the wing just the same length as in the smallest North American example, while in plumage it is precisely similar to 26,785, of the same age, from Jamaica. No. 4,367, from Puget’s Sound, Washington Territory,—also a young male,—has the wing of the same length as in the largest northern specimen, while the plumage is as usual.

Two adult females from Connecticut (Nos. 28,099 and 32,507, Talcott Mt.) are remarkable for their very deep colors, in which they differ from all other North American examples which I have seen, and answer in every particular to the description of F. cassini, Sharpe, above cited. The upper surface is plumbeous-black, becoming deep black anteriorly, the head without a single light feather in the black portions; the plumbeous bars are distinct only on the rump, upper tail-coverts, and tail, and are just perceptible on the secondaries. The lower parts are of a very deep reddish-ochraceous, deepest on the breast and abdomen, where it approaches a cinnamon tint,—the markings, however, as in other examples. They measure, wing, 14.75; tail, 7.50; culmen, 1.05–1.15; tarsus, 2.00; middle toe, 2.30. They were obtained from the nest, and kept in confinement three years, when they were sacrificed to science. The unusual size of the bill of these specimens (see measurements) is undoubtedly due to the influence of confinement, or the result of a modified mode of feeding. The specimens were presented by Dr. S. S. Moses, of Hartford.

An adult male (No. 8,501) from Shoal-water Bay, Washington Territory, is exactly of the size of the male described. In this specimen there is not the slightest creamy tinge beneath, while the blue tinge on the lower parts laterally and posteriorly is very strong. No. 52,818, an adult female from Mazatlan, Western Mexico, has the wing three quarters of an inch shorter than in the largest of four northern females, and of the same length as in the smallest; there is nothing unusual about its plumage, except that the bars beneath are sparse, and the ochraceous tinge quite deep. No. 27,057, Fort Good Hope, H. B. T., is, however, exactly similar, in these respects, and the wing is but half an inch longer. In No. 47,588, ♂, from the Farallones Islands, near San Francisco, California, the wing is the same length as in the average of northern and eastern specimens, while the streaks on the jugulum are nearly as conspicuous as in a male from Europe.