полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

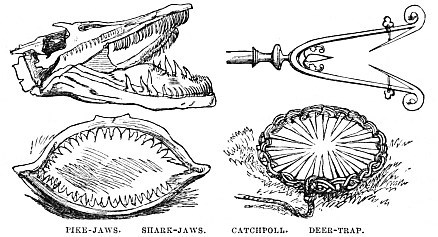

On the left hand of the illustration are two examples of the same principle taken from Nature, one belonging to fresh and the other to salt water.

The upper figure represents the jaws of a Pike, with their terrible array of reverted teeth. The Pike, as every one knows, feeds upon other fish, and eats them in a curious manner. It darts at them furiously, and generally catches them in the middle of the body. After holding them for a time, for the purpose, as I imagine, of disabling them, it loosens its hold, makes another snap, seizes the fish by the head, and swallows it.

The Pike is so voracious that it will attack and eat fish not very much smaller than itself, for its digestion is so rapid that the head and shoulders of a swallowed fish have been found to be half digested, while the tail was sticking out of the Pike’s mouth. Unless, therefore, the teeth of the Pike were so formed as to resist any retrograde movement on the part of the prey, the fish would starve; for, lank and lean as it is, the Pike is one of the most voracious creatures in existence, never seeming able to get enough to eat, and yet, as is often found in such cases, capable of sustaining a lengthened fast.

How well adapted is this arrangement of teeth for preventing the escape of prey, any one can tell who, in his early days of angling, caught a Pike, and, after killing it, tried to extract the hook without previously propping the jaws open. If once the hand be inserted between the jaws, to get it out again is almost impossible without assistance, and often has the spectacle been exhibited of a youthful angler returning disconsolately home, with his right hand in the mouth of a Pike, and supporting the weight of the fish with his left.

The teeth of a serpent are set in a similar manner, as can be seen by reference to the illustration on page 80. An admirable example of the power of this arrangement may be seen in the jaws of our common Grass or Ringed Snake (Coluber natrix). The teeth are quite small, very short, and not thicker than fine needle-points. Yet, when once the snake has seized one of the hind-feet of a frog, all efforts to escape on the part of the latter are useless. The lower jaw is pushed forward, and then retracted, and at each movement the leg is drawn further into the snake’s mouth, until it reaches the junction.

The snake then waits quietly until the frog tries to free itself by pushing with its other foot against the snake’s mouth. That foot is then seized, the leg gradually following its companion, and in this way the whole frog is drawn into the interior of the snake. I have seen many frogs thus eaten, but never knew one to escape after it had been once seized by the snake. As these reptiles are perfectly harmless, it is easy to try the experiment by putting the finger into a snake’s mouth, when it will be found that the assistance of the other hand will be needful in order to extricate it.

Below the head of the pike is a view of a Shark’s jaws, as seen from the front.

Here, again, we have a similar arrangement of teeth, row after row of which lie with their points directed towards the throat of the fish. As, however, the pike and the snake swallow their prey whole, their teeth need be nothing but points. But, as the Shark is obliged to mangle its prey, and seldom swallows it whole, its teeth are formed on a different principle, each tooth being flat, wide, sharply pointed, and having a double edge, each of which cuts like a razor. So knife-like are they, indeed, that when a whale is killed, the sharks which surround it bite off huge mouthfuls of blubber, and, as they swarm by hundreds, cause no small loss to the whalers.

Many a man has lost a leg by a shark, the fish having bitten it completely through, bone and all, and there have been cases where a shark has actually severed a man’s body, going off with one half, and leaving the other clinging to the rope by which he was trying to haul himself on board.

Spiked DefencesThis mode of defence is, perhaps, one of the most primitive in existence, and takes a wonderful variety of forms. The spiked railings of our parks and gardens, the broken glass on walls, and even the spiked collars for dogs, are all modifications of this principle.

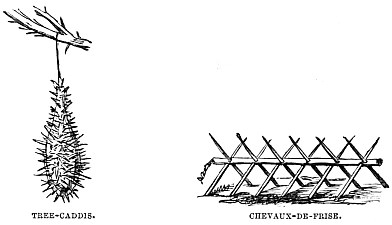

On the illustrations are several examples of spikes used for military purposes. The first is known by the name of “Chevaux-de-frise,” and is extensively used in forming an extemporised fence where no great strength is needed. The structure is perfectly simple, consisting of a number of iron bars with sharpened ends, and an iron tube some inches in diameter, which is pierced with a double set of holes. When not in use, the bars and tube can be packed in a small compass, but when they are wanted, the bars are thrust through the holes as shown in the illustration, and the fence is completed in a few minutes. The horizontal bars are linked together by chains, so as to prevent them from being shifted, and a defence such as this is generally used for surrounding parks of artillery and the like.

All who have the least acquaintance with military matters must be familiar with the “Square,” and its uses in the days of old. I say in the days of old, because in the present day the rapid development of guns and rifles has entirely destroyed the old arrangement. So lately, for example, as the day of Waterloo, troops might manœuvre in safety when they were more than two hundred yards from the enemy. Now, a regiment that attempted to manœuvre in open ground would be cut to pieces by the rifles of the enemy at a thousand yards’ distance.

In those days, however, the square was a tower of safety when rightly formed. It was formed in several rows. The outer line knelt, with the butts of their muskets on the ground, and the bayonet pointing upwards at an angle of forty-five. The others directed their muskets towards the enemy in such a manner that nothing was presented to him but the points of bayonets and the muzzles of loaded muskets. In all probability the battle of Waterloo would have been lost but for the use of the “square,” against which the French cuirassiers dashed themselves repeatedly, but in vain.

However admirable may be the organization of the square, whether it be hollow, or whether it be solid, like the “rallying square,” the principle is the same as that of the chevaux-de-frise.

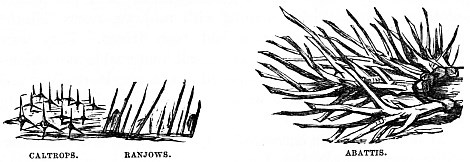

In the next illustration is shown the “Abattis,” one of the most important elements of extemporised fortifications, and as simple as it is important.

In any wooded country an abattis can be made in a very short time by practised hands. All that is required is to cut down the requisite number of trees, strip off the leaves and twigs, and then cut off the smaller branches with sloping blows of the axe, so as to leave a tolerably sharp point on each. The trees are then laid side by side, with the ends of the branches towards the enemy, and, the trunks being chained together, a wonderfully effective defence is constructed.

Not only is it almost impossible for the bravest and strongest man to force his way through the branches, even if the abattis were undefended, but the tree-trunks afford shelter for swarms of riflemen, who can pick off their assailants by aiming between the branches, themselves being almost unseen, and entirely covered.

In Southern Africa, during the late wars, the abattis was found to afford the best defence against the Kafirs, and that when the waggons and abattis were united so as to form a fortress, not even the naked Kafir, with all his daring courage, could force his way through them. Even artillery has but little power against the abattis, which allows the shot to pass between the branches, and is very little the worse for it. Accordingly, it is in great use for defending roads, especially those which are bounded by high banks, and makes a formidable obstacle in front of gates.

The two figures on the left of the same illustration represent two modes of carrying out the same principle, the one showing it as used in European warfare, and the other as a weapon of defence which has been employed from time immemorial, and is now in full use in many parts of the world.

Both these weapons are intended either to obstruct the approach of an enemy, or to cover the flight of a retreating force. The most simple and most ancient is the Ranjow, which is shown on the right hand of the illustration. The ranjow is nothing but a wooden stick varying in length from eighteen inches to nearly three feet, and sharply pointed at each end. In Borneo, China, &c., the ranjows are almost invariably made of bamboo, as that plant can be cut to a sharp point by a single stroke of a knife. (See page 59.)

When they are to be used, each soldier carries about a dozen or so of them, and sticks one end of them into the ground, taking care to make the upper end lean towards the enemy. Simple as are these weapons, they are extremely formidable, for it is necessary to pull up every ranjow before the troops can advance. Sometimes it has happened that a body of soldiers are driven over their own ranjows, and then the slaughter is terrible.

Some years ago a number of sketches were taken on the spot from scenes in the Chinese war. Among them was one that was absolutely terrible in its grotesqueness. It represented a piece of ground thickly planted with ranjows, over which the Chinese who had fixed them had been driven. They were simply hung with human bodies in all imaginable and unimaginable attitudes, some transfixed on a single ranjow, and others hanging on three or four, the body and limbs being alike pierced by them.

That ranjows were once used in Great Britain is evident from a discovery made by Col. Lane Fox. He had been excavating the soil around an old Irish fort, and deep beneath the bog he found a vast quantity of ranjows still set as the ancient warriors had left them. They were evidently used to defend a passage leading to the fort, and all of them were carefully set with their points outwards. Col. L. Fox was good enough to present me with several of these ancient weapons, which are now in my collection.

On the left is seen a piece of ground strewed with Caltrops, or Crow’s-feet, as they are sometimes called. These very unpleasant implements are made of iron, and have four sharp points, all radiating from one centre, so that no matter how they may be thrown, one point must be uppermost. They are used chiefly for the purpose of impeding cavalry, but I should think, judging from the specimens which I have seen, that infantry would find them very awkward impediments.

As for natural ranjows, they are so numerous that only a very few examples can be given.

The most perfect and most familiar example is, perhaps, the common Hedgehog, which, when rolled up, displays an array of sharp points so judiciously disposed, that it fears but very few foes. The same may be said of the Australian Echidna, or Porcupine Ant-eater, and the Porcupine itself. Whether the radiating bristles of the larva of the Tiger-moth, commonly called the Woolly Bear, come under the same category, I cannot say, but think it very likely.

Among vegetables the analogues are multitudinous. See, for example, the spikes of the Spanish and Horse Chestnuts, and especially the hair-like but formidable bristles which defend the common Prickly Pear. Indeed, all that tribe of plants is furnished so abundantly with natural ranjows, that a hedge of prickly pear forms the best defence which a house and garden can have.

Another example of natural ranjows is seen in the Tree-caddis, one of which is shown in the illustration on page 108, as it appears when suspended from a twig. It is the work of one of the House-builder Moths of the West Indies, and forms a sort of house in which the caterpillar can rest securely. It is built of bits of twigs and thorns, the latter being disposed so that their points are outwards, much after the fashion of a hedgehog’s spines.

I possess many specimens of Tree-caddis, evidently belonging to several species, and in all of them the principle is the same, i.e. a number of spikes set with their ends outwards in order to defend a central position.

Sometimes these spikes are left exposed, as shown in the illustration, and sometimes they are covered with a slight but strong web. The principle, however, is the same in all.

Now I shall have to use two very long words, and much against my will. I very much fear that, if most of my readers were to hear any one speak of the “repagula of Ascalaphus,” they would not be much the wiser. And yet there are no other words that can be used.

In the first place, Ascalaphus is a name belonging to a genus of Ant-lions, remarkable for having straight, knobbed antennæ, very much like those of a butterfly. This insect deposits its eggs in a double row on twigs, and then defends them with a series of natural ranjows, set in circular rows, and supposed to be without analogies in the animal creation. They are transparent, reddish, and “are expelled by the female with as much care as though they were real eggs, and are so placed that nothing can approach the brood; nor can the young ramble abroad until they have acquired strength to resist the ants and other insect enemies.”

The word “repagulum,” by the way, signifies a bar or barrier. A turnpike gate when closed would be a repagulum, and so would a chevaux-de-frise.

Tearing WeaponsWe have already had examples of weapons, like the Club, which bruise; of weapons, like the Spear and Dagger, which pierce; and of weapons, like the Sword, which cut. We now come to a totally distinct set of weapons, those which wound by tearing, and not by any of the preceding modes.

In civilised warfare we have long abandoned such weapons, as belonging to a barbarous age, but they are even yet employed in some parts of the world.

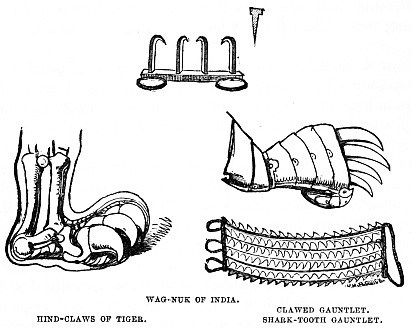

The accompanying illustration shows three examples of such weapons. One is the celebrated Tiger-claw of India, known by the native name of Wag-nuk. It is about two inches and a half in length, and is made to fit on the hand. The first and fourth fingers are passed through the rings, and the curved claws are then within the hand, and hidden by the fingers. The mode of employing this treacherous weapon was by engaging a foe in conversation, pretending to be very friendly, and then ripping up his stomach with an upward blow of the right hand.

It is comparatively a modern weapon, having been invented about two hundred years ago. A Hindoo, named Sewaja, was the inventor, and by means of the Wag-nuk he committed many murders unsuspected, the wounds being exactly like those which are made by the claw of the tiger. Sometimes there were four claws instead of three, as is the case with a specimen one in the Meyrick collection.

Perhaps the reader may be aware that the Transatlantic “knuckle-duster” is fitted on the hand in the same manner, only its object is to strike a heavy blow, and not to tear. History repeats itself, and the large and clumsy “cestus” of the ancient athlete is reproduced in the small but scarcely less formidable “knuckle-duster” of the modern rowdy.

The figures are remarkable, one representing the remaining epoch of chivalry, and the other that of barbarism. The upper figure shows a curious Gauntlet of the Middle Ages, in which the hand is not only defended by steel plates, but is also rendered an offensive weapon by the addition of four sharp spikes set just at the junction of the fingers with the hand. As long as the fingers are extended the spikes lie parallel with them, and are as harmless as a cat’s claws in their sheaths. But when the fingers are closed, as shown in the illustration, the spikes come into use, and can be made into a formidable weapon of offence, just as are the cat’s claws when protruded.

Below the gauntlet of civilised warfare is one of savage war, which has for many years been discontinued, partly on account of the introduction of firearms, and partly owing to the superficial coating of civilisation which is so easily adopted by the singular varieties of the human race which populate the isles where this remarkable weapon was once worn. The figure is taken from a specimen in the United Service Museum.

It is a Gauntlet, having at one end a band through which the whole hand is passed, and at the other three loops for the fingers, just like those of the Wag-nuk, which has already been described. The body of the weapon is made of cocoa-nut fibre, and upon it are strung six rows of sharks’ teeth, the tips all pointing backwards. It is a Samoan weapon, some of the most renowned warriors never using club nor spear, but trusting entirely to their terrible gauntlets. With these they struck right and left, dashing beneath the clubs and spears of their enemies, and always trying to rip up their stomachs, just as is done with the Wag-nuk. In order to guard against this weapon, the Samoan warrior wears a belt of cocoa-nut fibre some eight inches wide, and thick enough to defy the best gauntlet that could be made.

One celebrated Samoan warrior, a man of gigantic stature and strength, was addicted to the amusement of seizing his enemies with the shark-tooth gauntlets, breaking their backs across his knee, throwing them down, and going off after another victim.

On the left hand of the illustration is seen the hind-foot of the Tiger. I have chosen the hind-foot for two reasons: firstly, because the fore-foot has already been figured; and secondly, because the hind-foot is used for tearing open the abdomen of the prey. Any one who has played with a kitten has noticed how the animal throws itself on its back, clasps the wrist with its fore-paws, and kicks vigorously with its hind-legs. It does not mean to hurt its playfellow, but the hand does not easily escape without sundry scratches.

Child’s play though it may be in the kitten, it is no play at all with the tiger, or even the leopard, for either of these animals, when hard pressed, will throw itself on its back, clasp the foe in its fore-paws, and with the talons of the hind-feet tear him to pieces.

CHAPTER VI.

THE HOOK.—DEFENSIVE ARMOUR.—THE FORT

Anglers and their Hooks.—Single and double Hooks.—Hook of British Columbia.—Seed of Galium, or Goose-grass, and its Armature of Hooks.—Seed of the Burdock, and its Annoyance to Sheep.—Hooked Sponge-spicules.—“Snatching” Fish.—The Fish-rake of British Columbia.—The “Gaff” and its Uses.—The Jaguar as a Fisher—Defensive Armour and its Varieties.—Plate and Chain Mail.—The Shield.—Australian and West African Shields.—Fibre Armour.—Seal’s-tooth Cuirass.—Joints of Armour.—“Tassets.”—Scale Armour in Art and Nature.—The Manis and the Fish.—Feather Armour.—“Madoc in Aztlan.”—Quilted Armour of Silk or Cotton.—Terrible Results from the latter.—Mr. Justice Maulstatute.—Natural Quilt Armour.—The Rhinoceros and the Whale.—The Testudo of the ancient Romans, and its Uses.—The common Tortoise.—The Fort.—Curious Transitions in Fort building; first Earth, then Stone, then Earth again.—Advantage of Earthen Mounds.—Natural Snow-fort made by the Elk, and its Defensive Powers against the Wolf.

The HookHAVING now seen that the rod and line of anglers have their prototypes in Nature, we will proceed to the hook, by which the fish are secured.

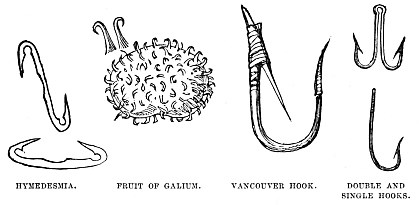

The two figures on the right hand of the accompanying illustration represent hooks which are familiar to every angler. The lower is the ordinary fish-hook, which can be used in so many ways. Generally it is employed singly, being fastened to the end of a line, and armed with a bait, either real or artificial. Sometimes, however, these hooks are whipped together, back to back, three or even four being so employed, and thus forming a combination of the hook and grapnel, and rendering the escape of a fish almost impossible.

Above it is a double hook, such as is used in “trolling” for pike, and with the use of which many of my readers are probably acquainted.

The third is a singularly ingenious hook made by the natives of British Columbia. It is almost entirely made of wood, with the exception of the barb, which is of bone. This, as the reader will see, is fixed, not to the point of the hook, as with us, but to its base, the point being directed towards the central portion of the curve.

At first sight this seems to be a singular arrangement, but it is a very effective one, as any one may see by placing the point between the fingers and pushing it through them. It will be found impossible to force it back again, the sharp point of the bone-barb coming against them and retaining them.

It has also another advantage. Very large fish, for which this hook is intended, are apt in their struggles to reverse the hook, and so to weaken its hold. In this hook, however, such a proceeding is impossible; for, even should the hook be reversed, it still retains its hold, the barb becoming the point, and the point keeping the lip of the fish against the tip of the barb. The figure is drawn from a specimen in my collection.

If the reader will look at the illustration, he will see a globular object covered with little hooks. This is a magnified representation of the seed-vessel of the common Goose-grass (Galium), which is so luxuriant in our hedges, and often intrudes itself into our gardens. Its long, trailing stems, with their tightly-clinging leaves, are familiar to all, and there are few who have not, while children, pelted each other with the little round green seed-vessels during the time that the fruit is in season. That they clung so tightly as not to be removed without difficulty, we all knew, but we did not all know the cause. The magnifying-glass, however, reveals the secret at once. The whole of the surface is covered with little sharp prickles, curved like hooks, and turned in all directions, so that, however it may be thrown, some of them are sure to catch.

So readily do these hooks hold to anything which they touch, that if a lady only sweeps her dress against a plant of Goose-grass, she is sure to carry off a considerable number of the seed-vessels, and to waste much time afterwards in picking them off.

The seed-vessel of the common Burdock, known popularly by the name of Bur, is armed in a similar manner, but, as it is much larger, it is easily avoided. Sheep suffer greatly from burs, which twist themselves among the wool so firmly that it is hardly possible to remove them without cutting away bur and wool together. As to a Skye terrier, when once he gets among burs, his life is a misery to him (I was going to say, a burden to him, but it would have looked like a pun).

Below, and on the left of the Galium-seed, are some spicules of the Hymedesmia, a sponge which is found on the coast of Madeira. The following account of it occurs in the Intellectual Observer, vol. ii. p. 312:—

“Fish-hook Spiculæ.—We have received from Mr. Baker, of Holborn, a slide containing spicules of the Hymedesmia Johnsonii, which are stated to be rare objects in this country. They have the form of a double fish-hook, and on the inner surface of each hook is an extremely sharp knife-edge projection, corresponding with a similar and equally sharp projection from the inside of the shank.”

“These minute knife-blades are so arranged that in addition to their cutting properties, they would act as barbs, obstructing the withdrawal of the hook. The two hooks attached to one shank are not in the same place, but nearly at right angles with one another, so that when one is horizontal the other is vertical, or nearly so. A magnification of four or five hundred linear does not in any way detract from the sharp appearance of the knife-edges, and they may take their place with the anchors of the Synapta as curious illustrations of the occurrence in living organisms of forms which man was apt to fancy were exclusively the products of his own contrivance and skill.

“We presume that these hooks of the Hymedesmia answer the usual purpose of spiculæ in strengthening the soft tissue, but they must likewise render the sponge an awkward article for the Madeira sea-slugs to eat.”