полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

One point of ingenuity must be mentioned, as it really belongs to the principle of the bait. These same savages, having noticed that large sea-birds are in the habit of hovering over the flying-fish, and would probably be seen by the Coryphenes, rig up a very long bamboo rod, tie to its end a large bundle of leaves and fibres, and then fix it in the stern of the boat, the sham bird being hung some twenty feet above the sham fish. There is a refinement of deception here, for which we should scarcely give such savages their due credit.

In Art, then, we bait our hooks either with real or false food, and so attract the fish.

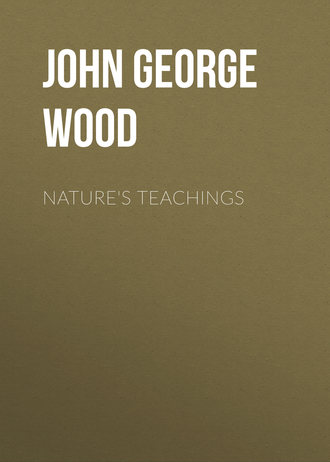

In Nature we have a most accomplished master of the art of baiting, who has the wonderful power of never needing a renewal of his bait. A glance at the left-hand figure of the next illustration will show that I allude to the Angler-fish, sometimes called the Fishing-frog (Lophius piscatorius). This remarkable creature has a most enormous mouth, and comparatively small body. On the top of its head are some curious bones, set just like a ring and staple, so as to move freely in every direction. A figure of this piece of mechanism will be given in a future page. At the end of these bones are little fleshy appendages, which must be very tempting to most fish, which are always looking out for something to eat. As they are being waved about, they look as if they were alive. The fish darts at the supposed morsel, and is at once engulfed in the huge jaws of the Angler-fish, which, but for this remarkable apparatus, would be scarcely able to support existence, as it is but a sluggish swimmer, and yet needs a large supply of food. The illustration, representing on the right hand a fish attracted to a bait, and on the left, the Angler-fish, with its bait-like appendage to the head, speaks for itself.

Passing to the art of Angling with a rod and line, we now arrive at another development.

Supposing a fish to have taken the bait, and to have been firmly hooked, how is it to be landed? The simplest plan is, of course, to have a very thick and strong line which will not break with the weight of any ordinary fish.

This is very well in sea-fishing, where a line made of whip-cord will answer the purpose in most cases. But, in river fishing, we have the fact that the fish are so shy that a linen thread would scare them, and so strong and active, that even whip-cord would not prevent them from breaking the line, or tearing the hook out of their mouths. So the modern angler sets himself to the task of combating both these conditions. In the first place, he makes the last yard or two of his line of “silkworm-gut”—a curious substance made from the silk-vessels of silkworms, and nearly invisible in the water. In the next place, he has a very elastic rod; and, in the third, he has forty or more yards of line, though perhaps only twenty feet are in actual use until the fish is hooked. The remainder of the line is wound upon a winch fixed to the handle of the rod. Thus, when a powerful fish is hooked and tries to escape, the line is gradually let loose, so as to yield to its efforts. When it becomes tired by the gradual strain, the line is again wound in, and in this way a fish which would at the first effort smash rod and line of a novice will, in the hands of an experienced fisherman, be landed as surely as if it were no bigger than a gudgeon.

Nature has in this case also anticipated Art, and surpassed all her powers.

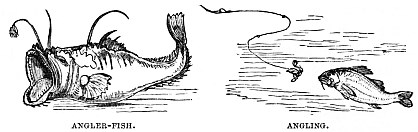

There is a wonderful worm, common on our southern coasts, and bearing, as far as I know, no popular name. It is known to the scientific world as Nemertes Borlasii. It possesses the power of extension and contraction more than any known creature, and uses those powers for the purpose of capturing prey. The fishermen say that this worm can extend itself to a length of ninety feet, and as Mr. Davis found one to measure twenty-two feet, after being immersed in spirits of wine, it is likely that their account may be true, especially as the spirit greatly contracted the animal in point of length.

A most vivid description of this worm is given by C. Kingsley, in his “Glaucus,” and was written before he knew its name.

“Whether we were intruding or not, in turning this stone, we must pay a fine for having done so; for there lies an animal as foul and monstrous to the eye as ‘hydra, gorgon, or chimæra dire,’ and yet so wondrously fitted to its work that we must needs endure for our own instruction to handle and to look at it. Its name I know not (though it lurks here under every stone), and should be glad to know. It seems some very ‘low’ Ascarid or Planarian worm.

“You see it? That black, shiny, knotted lump among the gravel, small enough to be taken up in a dessert spoon. Look now, as it is raised and its coils drawn out. Three feet, six, nine at least; with a capability of seemingly endless expansion; a slimy tape of living caoutchouc, some eighth of an inch in diameter, a dark chocolate black, with paler longitudinal lines.

“Is it alive? It hangs helpless and motionless, a mere velvet string, across the hand. Ask the neighbouring Annelids and the fry of the rock-fishes, or put it into a vase at home, and see. It lies motionless, trailing itself among the gravel; you cannot tell where it begins or ends; it may be a dead strip of seaweed, Himanthalia lorea, perhaps, or Chorda filum, or even a tarred string.

“So thinks the little fish who plays over and over it, till he touches at last what is too surely a head. In an instant a bell-shaped sucker mouth has fastened to his side. In another instant, from one lip, a concave double proboscis, just like a tapir’s (another instance of the repetition of forms), has clasped him like a finger; and now begins the struggle: but in vain. He is being ‘played’ with such a fishing-line as the skill of a Wilson or a Stoddart never could invent; a living line, with elasticity beyond that of the most delicate fly-rod, which follows every lunge, shortening and lengthening, slipping and twining round every piece of gravel and stem of seaweed, with a tiring drag such as no Highland wrist or step could ever bring to bear on salmon or on trout.

“The victim is tired now; and slowly, and yet dexterously, his blind assailant is feeling and shifting along his side, till he reaches one end of him; and then the black lips expand, and slowly and surely the curved finger begins packing him end foremost down into the gullet, where he sinks, inch by inch, till the swelling which marks his place is lost among the coils, and he is probably macerated to a pulp long before he has reached the opposite extremity of his cave of doom.

“Once safe down, the black murderer slowly contracts again into a knotted heap, and lies, like a boa with a stag inside him, motionless and blest.”

The accuracy as well as the pictorial effect of this description cannot be surpassed. The “velvety” feel of the creature is most wonderful, as it slips and slides over and among the fingers, and makes the task of gathering it together appear quite hopeless.

This astonishing worm is drawn on the left hand of the illustration on page 93, so as to show the way in which the body is contracted or relaxed at will. On the other side of the illustration is an angler, armed with all the paraphernalia of his craft, and doing imperfectly that which the Nemertes does with absolute perfection.

A similar property belongs to the long, trailing tentacles of the Cydippe, which is described and figured on page 16. When they come in contact with suitable prey, all struggle is useless, the tentacles contracting or elongating to suit the circumstances, and at last lodging the prey within the body of the Cydippe.

The Spring-trapWe are all familiar with the common Spring-trap, or Gin, as it is sometimes called.

It varies much in form and size, sometimes being square and sometimes round; sometimes small enough to be used as a rat-trap, and sometimes large enough to catch and hold human beings, in which case it was known by the name of man-trap. This latter form is now as illegal as the spring-gun, and though the advertisement “Man-traps and Spring-guns are set in these grounds” is still to be seen, neither one nor the other can be there.

They are all constructed on the same principle, namely, a couple of toothed jaws which are driven together by a spring, when the spring is not controlled by a catch. They are evidently borrowed from actual jaws, the same words being used to signify the movable portions and notches of the trap as are employed to designate the corresponding parts in the real jaw.

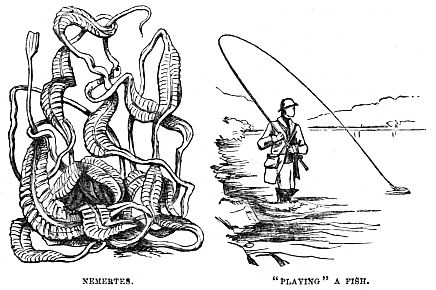

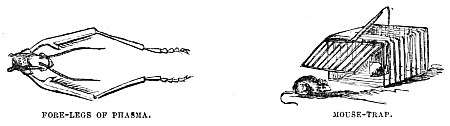

In both figures of the accompanying illustration we shall see how exact is the parallel. On the right hand is a common rat-trap, or gin, such as is sold for eightpence, with the jaws wide open, so as to show the teeth. On the left is a sketch of the upper and lower jaws of the Dolphin, in which an exactly analogous structure is to be seen.

The figure on the right hand of the lower illustration shows a man-trap as it appears when closed, the teeth interlocking so as exactly to fit between each other. The same principle is exhibited in the jaws of the Porpoise, which are seen on the left of the illustration. The jaws of an Alligator or Crocodile would have answered the purpose quite as well, inasmuch as their teeth interlock in a similar fashion, but I thought that it would be better to give as examples the jaws of allied animals. The reason for this interlocking is evident. All these creatures feed principally on fish, and this mode of constructing the jaws enables them to secure their prey when once seized.

Another example of such teeth is to be found in the fore-legs of various species of Phasma and Mantis, as may be seen by reference to the illustration. The latter insects are wonderfully fierce and pugnacious, fighting with each other on the least provocation, and feeding mostly on other insects, which they secure in their deeply-toothed fore-legs. They use these legs with wonderful force and rapidity, and it is said that a pair of these insects fighting remind the observer of a duel with sabres.

Our space being valuable, we are not able to give many examples of Baited Traps, whether in Art or Nature.

The most familiar example of this trap is the common Mouse-trap, the most ordinary form of which is shown at the right hand of the illustration on page 96. In all the varieties of these traps, whether for mice or rats, the prey is induced to enter by means of some tempting food, and then is secured or killed by the action of the trap. Sometimes these traps are made of considerable size for catching large game, and in Africa are employed in the capture of the leopard, in India for taking both tigers and leopards, and in North America for killing bears.

We have already noticed one instance of a bait in the Angler-fish, described in page 92, but in this case the bait serves only for attraction, and the trap, or mouth, is not acted upon by the prey.

There are, however, many examples in the botanical world, where the plant is directly acted upon by the creature which is to be entrapped, such being known by the now familiar term “Carnivorous Plants.” Of these there is a great variety, but under this head I only figure two of them.

The plant on the right hand is the Venus Fly-trap (Dionea muscipula), which is common in the Carolinas. The leaves of this plant are singularly irritable, and when a fly or other insect alights on the open leaf, it seems to touch a sort of spring, and the two sides of the leaf suddenly collapse and hold the insect in their grasp. The strange point about it is, that not only is the insect caught, but is held until it is quite digested, the process being almost exactly the same as if it had been placed in the stomach of some insect-eating animal.

So carnivorous, indeed, is the Dionea, that plants have been fed with chopped meat laid on the leaves, and have thriven wonderfully. Experiments have been tried with other substances, but the Dionea would have nothing to do with them. The natural irritability of the leaves caused them to contract, but they soon opened and rejected the spurious food.

On the left is the Cephalotus. This plant, instead of catching the insect by the folding of the leaf, secures it by means of a sort of trap-door at the upper end. The insect is attracted by the moisture in the cup, and, as soon as it enters, the trap-door shuts upon it, and confines it until it is digested, when the door opens in readiness to admit more prey.

BirdlimeBy a natural transition we pass to those traps which secure their prey by means of adhesive substances.

With us, the material called “birdlime” is usually employed. This is obtained from the bark of the holly, and is of the most singular tenacity. An inexperienced person who touches birdlime is sure to repent it. The horrid stuff clings to the fingers, and the more attempts are made to clear them, the more points of attachment are formed. The novice ought to have dipped his hands in water before he touched the birdlime, and then he might have manipulated it with impunity.

The most familiar mode of using the birdlime is by “pegging” for chaffinches.

In the spring, when the male birds are all in anxious rivalry to find mates, or, having found them, to defend them, the “peggers” go into the fields armed with a pot of birdlime and a stuffed chaffinch set on a peg of wood. At one end of this peg is a sharp iron spike. They also have a “call-bird,” i.e. a chaffinch which has been trained to sing at a given signal.

When the “peggers” hear a chaffinch which is worth taking, they feel as sure of him as if he were in their cage. They take the peg, and stick it into the nearest tree-trunk. Round the decoy they place half-a-dozen twigs which have been smeared with birdlime, and arrange them so that no bird flying at the decoy can avoid touching one of them.

The next point is, to order the call-bird to sing. His song is taken as a personal insult by the chaffinch, which is always madly jealous at this time of year. Seeing the stuffed bird, he takes it for a rival, dashes at it, and touches one of the twigs. It is all over with him, for the more he struggles and flutters, the tighter is he bound by the tenacious cords of the birdlime, and is easily picked up by the “pegger.”

Even the fierce and powerful tiger is taken with this simple, but terrible means of destruction. It is always known by what path a tiger will pass, and upon this path the native hunter lays a number of leaves smeared with birdlime. The tiger treads on one of them, and, cat-like, shakes his paw to rid himself of it. Finding that it will not come off, he rubs his paw on his head, transferring the leaf and lime to his face.

By this time he is in the middle of the leaves, and works himself into a paroxysm of rage and terror, finishing by blinding himself with the leaves that he has rubbed upon his head. The hunters allow him to exhaust his strength by his struggles, and then kill him, or, if possible, capture him alive.

Both these scenes are represented on the right hand of the illustration.

On the left hand are several examples of natural birdlime, if we may use the term. The upper represents the Ant-bear, or Great Ant-eater. This animal feeds in a very curious manner. It goes to an ant-hill, and tears it open with its powerful claws. The ants, of course, rush about in wild confusion. Now, the Ant-eater is provided with a long, cylindrical tongue, which looks very like a huge earth-worm, and which is covered with a tenacious slimy secretion. As the ants run to and fro, they adhere to the tongue, and are swept into the mouth of their destroyer.

Below the Ant-eater is the common Drosera, or Sundew, one of our British carnivorous plants. It captures insects, just as has been narrated of the Dionea. But, instead of the leaf closing upon the insect, it arrests its prey by means of little globules of viscous fluid, which exude from the tips of the hairs with which the surface of the leaf is covered. As soon as the insect touches the hairs, they close over it, bind it down, and keep it there until it is digested. Several species of Drosera are known in England, and are found in wet and marshy places.

Another plant, the Green-winged Meadow Orchis (Orchis morio), has been known to act the part of the Drosera. A fly had contrived to push its head against the viscous fluid of the stigmatic surface, and, not being able to extricate itself, was found sticking there.

Next comes a portion of the web of the common Garden Spider (Epeira diadema). We have already treated of this web as a net, and we will now see how it comes within the present category.

In the web of the spider there are at least two distinct kinds of threads. Those which radiate from the centre to the circumference are strong and smooth, while those which unite them are much slighter, and are covered with tiny globules set at regular intervals. When the web is newly spun, these globules are found to be nearly as tenacious as birdlime, and it is by these means that an insect which falls into the web is arrested, and cannot extricate itself until the spider can seize it. After awhile the globules become dry, refuse to perform their office, and then the spider has to construct another web. So numerous are these globules that, according to Mr. Blackwall’s calculations, an ordinary net contains between eighty and ninety thousand. Below the figure of the web itself are shown the two kinds of thread, the upper bearing the globules, and the lower representing one of the plain radiating threads.

CHAPTER V

Reverted Spikes and their Modifications.—The Wire Mouse-trap.—George III. and the Trap.—Fate of a Royal Finger.—The Crab and Lobster Pot.—The Eel-pot.—Cocoon of the Emperor-moth and its Structure.—“Catchpoll” of the Middle Ages.—Deer-trap of India.—Jaws of Pike and Serpent.—The Grass-snake.—Jaws of Shark and their Power.—Spiked Defences.—The Park Fence, the Garden Wall, and the Chevaux-de-frise.—The “Square” of Infantry Manœuvres.—The Abattis, and its Structure and Power.—Ranjows and Caltrops.—Ancient Ranjows in Ireland.—Hedgehog.—Porcupine Echidna.—House-builder Caterpillar and its Home.—Repagula of Ascalaphus.—Tearing Weapons.—The “Wag-nuk” of India.—Armed Gauntlet of the Middle Ages.—Shark-tooth Gauntlet of Samoa, and the Uses to which it was put.—A terrible Warrior.—The Tiger’s Claw.—Sport and Earnest.

Reverted SpikesI am not quite satisfied with this title, but it is the best that I can find. By it I mean that mode of mechanism which, by means of an array of sharp spikes, permits an animal to enter a passage easily, and yet prevents it from emerging.

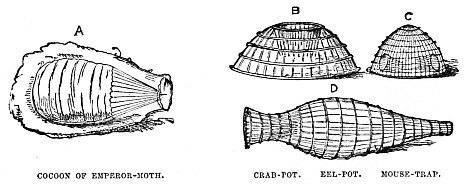

Whether or not this principle be now employed in warfare I cannot say, but it is at all events used extensively in a small way of hunting, the best known of which is the wire Mouse-trap, one of which is shown at Fig. C on the illustration. A glance at the figure will explain the trap, even to those who have never seen it. It is composed entirely of wire, and has several round holes just above its lower edge. Each of these holes is the entrance to a conical tunnel made of wires with sharpened ends.

The mouse, being attracted by a bait placed within the trap, tries to get at it. The doomed animal soon finds its way to one of the entrances, and with little difficulty pushes itself through the tunnel. Entering, however, is one thing, and returning is another. The wire yielded easily enough in one direction, but for the mouse to force itself against the converging points is an impossible task.

Readers of the last century literature may perhaps remember, in the pages of “Peter Pindar,” a very clever and sarcastic account of the astonishment created in the mind of George III. by a mouse-trap seen accidentally in the house of a widow living at Salt Hill.

“Eager did Solomon, so curious, clapHis rare round optics on the widow’s trap,That did the duty of a cat.And, always fond of useful information,Thus wisely spoke he with vociferation,—‘What’s that? what? what? Hæ, hæ? what’s that?’To whom replied the mistress of the house,‘A trap, an’t please you, sir, to catch a mouse.’‘Mouse—catch a mouse!’ said Solomon with glee;‘Let’s see, let’s see—’tis comical—let’s see—Mouse! mouse!’—then pleased his eyes began to roll—‘Where, where doth he go in?’ he marvelling cried.‘There,’ pointing to the hole, the dame replied.‘What! here?’ cried Solomon, ‘this hole? this hole?’Then in he pushed his finger ’midst the wire,That with such pains that finger did inspire,He wished it out again with all his soul.”For my part I think that the King was quite right. If he did not know the philosophy of a mouse-trap he ought to have asked, and to have been rewarded, as in that case, by catching with a trap of his own baiting, six mice on six successive days.

At Fig. B on the same illustration is shown the simple apparatus by which crabs and lobsters are caught. The reader will see that the principle is exactly the same in both cases, the only difference being in material, the mouse-trap being made of wire, and the crab-pot of wicker.

At Fig. D is shown the common Eel-pot, or Eel-basket. In order to suit the peculiar shape of an eel, this basket is much longer in proportion to its diameter than either of the preceding traps, but it is formed on the same plan. An eel can easily pass into the basket through the conical tunnel, but it is next to impossible that it should find its way out again.

So much for Art, and now for Nature.

On the left hand of the illustration, at Fig. A, is the cocoon of the common Emperor-moth (Saturnia pavonia minor), the cocoon having been stripped of its outer envelope, so as to allow its structure to be better seen.

The reader will at once perceive that the entrance of the cocoon is guarded by an arrangement exactly like that of the above-mentioned traps, except that the cone is reversed, so as to allow of exit and to debar entrance. Guarded by this conical arrangement of stout bristly appendages, the pupa can remain in quiet during the time of its transformation, for nothing can force its way through such a defence, and yet the moth, when fully developed, can push its way out with perfect ease.

So admirably is this cocoon formed, that even after the moth has escaped, it is impossible to tell by mere sight whether or not it is within, the elastic wires closing on it after its passage.

Another modification of the same principle now comes before us. In the above-mentioned examples the arrangement of the reverted spikes is more or less conical, and they lead into a chamber. In the present instances, however, the mere reversion of the points is all that is needed.

The upper figure on the right hand represents the “Catchpoll” of the Middle Ages, an allusion to which has already been made. The reverted spikes turn on hinges, and are kept apart by springs. This beautifully formed head was attached to a long shaft, and was used for the purpose of dragging horsemen from the saddle. It was thrust at the neck of the rider, generally from behind. If a successful thrust were made, the spring-points gave way, sprang back again, and thus clasped the neck with a hold that was fatal to the rider.

Below it is the Deer-trap which is used in many parts of India, and to which allusion has already been made. The reader will see at once that if a deer should get its foot through the converging spikes, its doom is sealed, especially as there is a heavy log of wood attached to the trap by a rope.