полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

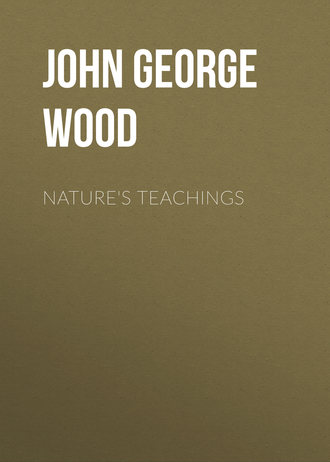

We now come to another modification of the hook. I presume that many of my readers have heard of the practice called “snatching” fish, though I hope that they have never been unsportsmanlike enough to follow it.

This plan, which is only worthy of poachers, consists in taking several flights of treble or quadruple hooks, dropping them gently by the side of the fish, and then, with a sudden jerk, driving them into any part of its body which they may happen to strike. Most anglers have snatched fish accidentally, but to do so intentionally is ranked among the worst of an angler’s crimes, and is equivalent to cheating at cards, or playing with false dice.

In some parts of the world, however, there are certain small fish which are never taken in any other way, and, indeed, are raked out of the water just as a gardener rakes dead leaves off the path or beds.

In British Columbia there are certain lakes tenanted largely with small fish which form a considerable portion of the natives’ diet. They swim in vast shoals close to the surface of the water, and are captured by veritable rakes, one of which is shown in the illustration. The points of the rake are slightly curved, and very sharp, and so numerous are the fish that when the native has struck his rake among the shoal, and drawn it into the boat, he generally finds a fish on every tooth, while it often happens that two or three are transfixed by the same tooth. A sharp knock against the side of the boat shakes off the prey, and the fisherman again strikes his rake into the shoal. By this simple mode of fishing a couple of men will, in a few hours, load a canoe with small but valuable fish.

Below the rake is the “Gaff,” an instrument, not to say a weapon, which is indispensable when salmon or other large fish are to be caught. For ordinary-sized fish a landing-net is sufficient, but no landing-net could either receive or retain a salmon of any size.

Recourse is then had to the Gaff, which is simply a huge hook at the end of a handle. The fish being “played” until it can be drawn within reach, the gaff is slipped under it, struck into the side of the salmon, and by its aid the fish is easily lifted out of the water.

On the left hand of the illustration are two figures showing how the principle of the fish-rake and gaff has been anticipated in Nature.

It is a well-known fact that the Jaguar feeds largely on fish, which it catches for itself. It goes down to the river-side as close to the water as possible, and waits patiently for its prey. As soon as a fish comes within reach, the Jaguar stretches out its paw to the fullest extent, and, with a stroke of the curved claws, hooks the fish on shore, just as the Vancouver Islander does with his fish-rake, or the English angler with his gaff.

Many persons have practically experienced the gaff-like powers of the feline claw by the loss of their gold-fish. It is seldom safe to leave a globe of gold-fish within reach of a cat. Nearly all cats are madly fond of fish, and, in spite of their instinctive hatred of water, will hook out the fish with their claws, and eat them. Indeed, there are several instances on record where a cat has regularly caught fish, and brought them home to its owner. Mr. F. Buckland gives an account of a fisherman’s cat, which used to go out with her master, jump into the sea, secure a fish, and then be lifted on board with her prey.

Above the Jaguar is drawn a single claw, so as to show the form of the instrument by which the fish is captured.

ArmourWe will now take the subject of Defensive Armour, by which warriors are enabled to protect themselves against the offensive weapons of the enemy.

As many readers will probably know, armour reached its greatest development in the Middle Ages, when the knight was so completely cased in steel that no weapon then in use could penetrate his panoply.

The head, body, and limbs were covered with steel plates curiously articulated at the joints, so as to give freedom of motion, while guarding the wearer from any ordinary weapon. A warrior might be beaten from his horse by a mace, or struck down by a lance, or the horse itself might be killed under him.

In either of these cases the fallen knight was not much the worse, until a weapon called the “Misericorde,” or dagger of mercy, was invented. This was a poniard with a very slender and very sharp blade, so constructed that it could be driven between the joints of the armour, and thus inflict a mortal wound. The Misericorde, however, was baffled by the use of chain or scale armour under the plate-mail, and then the only way of getting at the fallen knight was by breaking up the armour with hammers which were made for this express purpose.

Perhaps the reader may wonder that any one should lie quietly and allow himself to be so badly treated. The very strength of the armour, however, which rendered its wearer unassailable by ordinary weapons, involved so much weight, that when a knight had fallen, it was impossible for him to rise, much less to mount a horse, without help. Moreover, the first blow of a weighty hammer on the helmet would, although it could not kill the wearer, cause such a jar to his brain as partially, if not wholly, to stun him.

The rapidly increasing power of firearms soon caused armour to be laid aside, and now the only remains of it are to be found in the helmets and cuirasses worn by our dragoons.

There are few parts of the world where armour of some sort is not used. Putting aside civilised or semi-civilised nations, we find that in most cases, wherever there is war, there is armour of some kind. Sometimes it is movable, and in that case is called a shield.

The most singular shields that I know are those made by the Australians, which are so shaped that no one who did not know their use would take them for shields. They are about three feet long, four inches wide at the back, six inches or so thick in the middle, tapering towards the ends, and coming to an edge in front. They are held by the centre with one hand, so that they can be rapidly twisted from side to side, and so serve to parry the spear or stop the boomerang. The weight of the shield enables it to withstand the shock of the boomerang, which whirls through the air with terrific force.

Several warlike savage tribes have, however, no armour of any kind, such as the New Zealanders, the Samoans, and the Fijians.

Sometimes the armour is affixed to the body, and of such protection many examples are to be found in various museums, among which the Christy collection is pre-eminent.

Among the Polynesians cocoa-nut fibre was at one time employed as the material for armour. It was twisted into small cords, and with these a sort of armour was constructed, quite strong enough to resist any weapon that an enemy of their own kind could bring against them. Sometimes this armour was merely a belt wide enough to protect the abdomen, but sometimes the whole body was defended, from the neck to the hips.

In the United Service Museum there is a very remarkable cuirass, which is made of successive rows of seals’ teeth, each row overlapping the other like the tiles of a house. It is very heavy, weighing quite as much as a steel cuirass, and was probably quite as effective against the primitive weapons which could be brought to bear upon it.

Now for Natural Armour.

There are so many examples of armour, as furnished by Nature, that I can only mention a few.

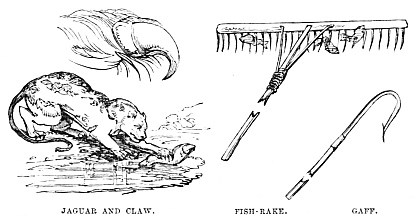

Any one who looks at a lobster, crayfish, prawn, or shrimp, must at once see that in it lies the prototype of plate armour. That portion of the lobster which is popularly called the head, and is scientifically known as the “carapace,” is not jointed, and corresponds with the cuirass of ancient or modern armour. Then comes the part called the “tail,” the joints of which are exactly like those employed in the shoulders, elbows, knees, and ankles of ancient armour. The lobster tail will again be mentioned in connection with another branch of human art.

As for the heavy, ungraceful armour which was used in tilting, we have an admirable example in the Trunk-fish of the tropical seas (Ostracion), the whole of which is enclosed in a bony case, the fins and tail protruding through openings in it. In fact, the scales, instead of being separate, are fused together so as to form a continuous covering. The Box-tortoise of South America is another good example, the creature being furnished with bony flaps with which it covers the apertures through which the head, legs, and tail are protruded, and so is as impervious as the knight of old.

In the later ages of armour, the thighs, instead of being enclosed in steel coverings with cuisses, were defended by a number of steel plates called “tassets.” Now these tassets are exactly like the defensive armour of the Armadillo’s back, and, though it is not likely that the inventor of tassets should have seen an Armadillo, the fact still remains, that Art has been anticipated by Nature.

Exactly the same principle is seen in that wonderful little animal, the Pichiciago of South America, which is shown in the lower left-hand figure of the illustration. This creature is not only furnished with bony rings on the body like those of the Armadillo, but has likewise a flap which comes over the hindquarters, and effectually defends it against the attacks of any foe that might pursue it into its burrow.

In the lower right-hand corner of the illustration is seen a figure of a Chiton, several species of which are common on most of our coasts. This is one of the molluscs, which adheres to the rock just as limpets do. But, whereas the shell of the limpet is all in one piece and inflexible, that of the Chiton is composed of several pieces, which are arranged exactly like the tassets of armour, and enable the Chiton to accommodate itself to the inequalities of the rocks to which it is adhering.

The common Pill Millipede, which rolls itself up in a ball when alarmed, is a familiar instance of similar defensive armour, and much the same may be said of the Julus Millipede.

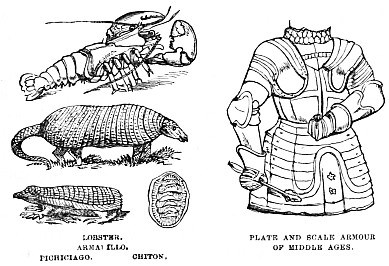

We now come to Scale Armour, which is one of the earliest modes of protecting the body, and the idea of which was clearly taken from animal life. In Scale Armour, flat plates of metal, horn, or bone are sewn to a linen or leathern vest in such a way that the scales overlap each other, and so tend to throw off the blow of a weapon. One great advantage of this armour is its lightness and flexibility, the former quality allowing of more prolonged exertion than could be possible with the heavy plate armour, and the latter rendering that exertion less fatiguing to the limbs.

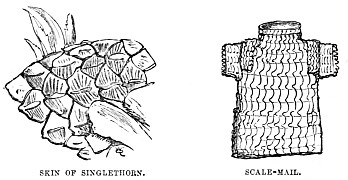

A glance at the preceding illustration will show how the scale armour of the human warrior has been anticipated by Nature.

On the right hand is an example of ordinary scale armour, while on the opposite side is a portion of a scaly surface. This figure represents some of the scales of a Manis. These scales are wonderfully hard, and scarcely to be penetrated. I have in my collection the skin of a Short-tailed Manis, which had been kept for some time in an Indian compound, but which made itself such a nuisance by its perpetual burrowing, that its owner was forced to condemn it to death.

So he took a Colt’s revolver, and fired at it from a distance of a yard or two. The only result was to knock over the Manis, which rolled itself up, and appeared to be none the worse. A second and a third shot were fired with similar results, and the last bullet recoiled upon the firer. At last, the animal was killed by introducing the point of a dagger under the scales, and driving it in with a mallet. The Manis itself is given in the illustration on page 189.

Again, the scales of most fishes afford excellent examples of scale armour. I have selected one, the Japanese Singlethorn, on account of the strength of the scales, each of which is deeply ridged and furrowed. The reader will probably have noticed that the skin of the animal, into which are inserted the bases of the scales, is analogous to the linen or leathern foundation upon which the artificial scales are sewn.

Even feathers give a better protection than might be imagined from their individually fragile structure. This is well shown in the case of aquatic birds, whose feathers are very closely pressed together, each overlapping the next, and set in regular order. Not only is the plumage rendered water-tight, but it is able to resist a severe blow. This is well known by sportsmen, who do not fire at ducks or geese while they are approaching, knowing that their shot would only glide harmlessly from the feather-mail of the bird.

They wait until the birds have passed, and then find no difficulty in killing them, the shot penetrating under the feathers just as did the dagger under the scales of the manis. Even the diminutive puffin, or sea-parrot, as it is sometimes called, cares little for shot while it is sitting on the rocks with closed wings and feathers pressed together. When, however, it takes to flight, it can be killed without difficulty.

Perhaps some of my readers may be aware that the ancient Mexican warriors wore armour made of feathers, which I presume must have been arranged much after the fashion of those of a duck’s breast.

This remarkable Feather-mail is mentioned by Southey in his poem, “Madoc in Aztlan.” In canto xviii, is recounted the single combat between Madoc and Coanocotsin, the King of Aztlan. The contrasting armour and weapons of each are graphically described, and especial mention is made of the cuirass:—

“Over the breast,And o’er the golden breastplate of the King,A feathery cuirass, beautiful to eye,Light as the robe of peace, yet strong to save;For the sharp faulchion’s baffled edge would glideFrom its smooth softness.”Then, in the course of the combat, when the King has been grappled in Madoc’s arms and forced to drop his buckler and club, the narrative proceeds:—

“Which when the Prince beheld,He thrust him off, and drawing back, resumedThe sword that from his wrist suspended hung,And twice he smote the King. Twice from the quiltOf plumes the iron glides.”If such armour could in truth resist the weapons which have been discovered, it must have been a wonderfully strong garment, for the Mexican swords, though made of wood, are edged with flakes of obsidian, which cuts like a razor. I have a number of these flakes, which have evidently been intended for the edges of a sword, but have not been used.

There is another kind of armour which is still used in some parts of the world, and at one time was employed in this country. This is the Quilt Armour, which is made by enclosing a thick layer of some fibre, such as silk or cotton, between two pieces of fabric, and then sewing them across and across, so as to keep the lining or stuffing in its place.

The eider-down quilts are familiar examples of such fabrics, and so are the quilted petticoats, which are so comfortable in winter. Horsehair and flock mattresses are made in a similar manner.

Insufficient as it may appear to be, the quilt armour, when well made, is really proof against most weapons, even against firearms, as we shall presently see. Being very much lighter than steel, it was easier for the wearer, its chief drawback being that its extreme thickness gave it a very clumsy and awkward look. Those who wore it, however, cared more for their safety than their appearance, as was exemplified by James I., who lived in perpetual fear of assassination, but who had a nervous dislike to arms, whether offensive or defensive. He therefore wore a cuirass quilted with silk, which answered every purpose of defence, while it did not offend his nerves.

Perhaps the reader may remember that in “Peveril of the Peak” Sir Walter Scott gives a ludicrous picture of the timid justice, his fears of the Popish plot, his suit of quilted armour, and his “Protestant Flail” with which he hits himself on the head instead of striking his supposed enemy:—

“Some ingenious artist, belonging, we may presume, to the worshipful Mercers’ Company, had contrived a species of armour of which neither the horse armoury in the Tower, nor Gwynnap’s Gothic Hall, no, nor Dr. Meyrick’s invaluable collection of ancient arms, has preserved any specimen.

“It was called Silk-armour, being composed of a doublet and breeches of quilted silk, so closely stitched, and of such thickness, as to be proof against either bullet or steel, while a thick bonnet of the same materials, with ear-flaps attached to it, and on the whole much resembling a nightcap, completed the equipment, and ascertained the security of the wearer from the head to the knee. Master Maulstatute, among other worthy citizens, had adopted this singular panoply, which had the advantage of being soft, and warm and flexible, as well as safe. And he was sat in his judicial elbow-chair—a short, rotund figure, hung round, as it were, with cushions, for such was the appearance of the quilted garments—and with a nose protruded from under the silken casque, the size of which, together with the unwieldiness of the whole figure, gave his worship no indifferent resemblance to the sign of the Hog in Armour, which was considerably improved by the defensive garment being of a dusky orange colour, not altogether unlike the hue of those half-wild swine which are to be found in the forests of Hampshire.”

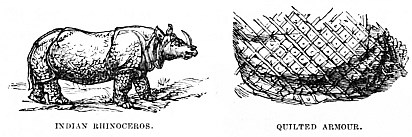

Roger Nutt gives as a reason for the security of quilted armour, that it made the wearer look so ridiculous that no one could hit him for laughing. The reader will probably remember that the sign of the Hog in Armour was really a representation of the rhinoceros.

That such a cuirass is really impervious to ordinary weapons is shown by the following anecdote:—During one of the late Indian wars a trooper discharged his pistol close to the back of a fleeing horseman. The shot produced no apparent effect, and the man rode off. Presently, however, a thin cloud of smoke was seen to rise from his shoulders. The smoke thickened, then burst into flame, and after riding at desperate speed in hopes of overtaking his comrades, the unfortunate man fell from his horse, and was miserably burned to death.

The fact was that cotton being cheaper than silk, he had wadded his cuirass with cotton fibre. Had he chosen silk, he would have got off in safety. Among the Chinese this cotton mail is largely used. In consequence, many Chinese soldiers were found who had been burned to death in exactly the same way as the Indian warrior.

Towards the south-western parts of Africa there is a nation called the Begharmis. Their soldiers are mounted, and are all furnished with suits of quilted mail, which fall below the knee as the rider is seated on his horse. Not only is the rider thus defended, but the horse also, which is covered with quilted armour like that of its rider, the appearance of both being exceedingly grotesque.

There are several examples of such armour in the animal world, the principal of which is the Indian Rhinoceros. Any one who has seen this animal, or even a good portrait of it, will at once recognise the parallel between the heavy folds of its thick skin and the padded flaps of the quilted mail. The blubber with which the whale is so thickly coated affords another example of the parallel between Nature and Art.

In the days of ancient Rome there was a curious military manœuvre, by which the defensive armour of individual soldiers might be made collectively useful. This manœuvre was called Forming a Tortoise (testudinem facere), and is thus described in Smith’s “Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities:”—

“The name of Testudo was also applied to the covering made by a close body of soldiers, who placed their shields over their heads to screen themselves against the darts of the enemy. The shields fitted so closely together as to present one unbroken surface without any interstices between them, and were so firm that men could walk upon them, and even horses and chariots be driven over them.

“A Testudo was formed either in battle, to ward off the arrows and other missiles of the enemy, or, which was more frequently the case, to form a protection to the soldiers when they advanced to the walls or gates of a town for the purpose of attacking them.

“Sometimes the shields were disposed in such a way as to make the Testudo slope. The soldiers in the first line stood upright, those in the centre stooped a little, and each line successively was a little lower than the preceding, down to the last, where the soldiers rested on one knee. Such a disposition of the shields was called Fastigata Testudo, on account of their sloping like the roof of a building.

“The advantages of this plan were obvious. The stones and missiles thrown upon the shields rolled off them like water from a roof; besides which, other soldiers frequently advanced upon them to attack the enemy upon the walls. The Romans were accustomed to form this kind of Testudo as an exercise in the games of the Circus.”

On the right hand of the illustration is shown a portion of a Testudo of three ranks, taken from the Antonine column. On the left is an ordinary Tortoise. Sometimes the Testudo was a covered machine on wheels, and guarded above with a supplementary roof of wet hides arranged in scale fashion, so as to prevent it from being set on fire by the besieged, and to throw off the heavy missiles which were dropped upon it. Under cover of this Testudo, the soldiers could either undermine the walls, or bring a battering-ram to bear upon them, while the men who worked it were safely under cover. As to the battering-ram itself, we shall presently treat of it.

The FortAs we have treated of one of the modes by which Forts were assaulted, we will now come to the Fort itself.

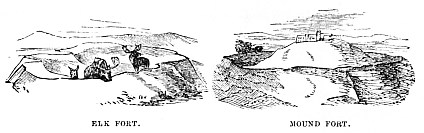

The transitions in Fort-making are too curious to be omitted from the present book. As soon as war became organized, a Fort of some kind was necessary. The simplest mode of making a Fort was evidently to dig a deep trench, and throw up the earth on the inside, so as to form a wall. Let such a trench be square or circular, and there is a simple but powerful Fort, by means of which a comparatively small garrison could defend themselves against a superior force.

The Romans were great masters of this art, fighting as much with the spade as the sword. So strong and thorough was the old Roman work that many of their camps still remain, and will remain for centuries if man does not deface them. Such, for example, are Cæsar’s camp, near Aldershot, and the fine camp at Lyddington, in Wiltshire, almost every detail of which is preserved. Roman camps are all constructed on the same model, the general’s place, or Prætorium, being in the centre, whence he issued his orders, and the commanders under him occupying the corners. Thus, no matter how he might be shifted from one corps to another, every Roman soldier knew his way about the camp without needing to see it, and could tell at any moment where to find any officer.

Other nations made their Forts circular, an example of which I lately saw a few miles from Bideford, while others consisted of nearly parallel lines, enclosures, and demi-lunes, like those wonderful dykes near Clovelly, which occupy more than thirty acres of land. One of the circular Forts is shown on the right hand of the illustration.

As time went on, stone took the place of earth, and the principal object of the builder was to give considerable thickness below, so as to resist the battering-ram, and great height both to walls and towers, so as to be comparatively out of the reach of the arrows and other missiles of the besiegers.

For awhile, such castles were impregnable, and the owners thereof were the irresponsible despots of the neighbourhood, recognising no law but their own will, robbing, torturing, and murdering at pleasure, and setting the king at open defiance. When, however, the tremendous powers of artillery became developed, the age of stone castles passed away. Height was found to be equivalent to weakness, as the strongest tower in existence could be knocked to pieces in an hour or two, and do infinite harm within the fortress by its falling fragments.