полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

It is worthy of notice that the term “noiselessly destructive” weapon, as applied to the air-gun, is entirely false. I have already mentioned that with the blow-gun of tropical America a definite explosion accompanies the flight of each arrow. The same result occurs with the air-gun, the loudness of the report being in exact proportion to the force of the air, each successive report becoming slighter and the propulsive power weaker until a new supply of air is forced into the chamber.

However dissimilar in appearance may be the cannon, rifle, pistol, or any other firearm, to the pea-shooter and its kin, the principle is exactly the same in all. It has been already mentioned that in the blow-guns the air is compressed by the exertion of human lungs, and in the air-gun the compression is achieved by human hands.

But with the firearm a vast volume of expansible gas is kept locked up in the form of gunpowder, gun-cotton, fulminating silver, or other explosive compound, and is let loose, when wanted, by the aid of fire.

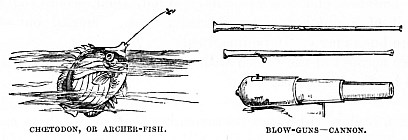

In the illustration are represented on the right hand the blow-guns of America and Borneo, and below them is the cannon as at present made. On the left hand of the same illustration is seen a representation of a natural gun which has existed for thousands of years before gunpowder was invented, and very long before the savage of Borneo or America discovered the blow-gun.

It is the Archer-fish (Chœtodon), which possesses the curious power of feeding itself by shooting drops of water at flies, and very seldom failing to secure its prey.

There are several species of this very curious fish spread over the warmer parts of the world, and their remarkable mode of obtaining prey is very well known in all. There is, indeed, scarcely any phenomenon in Nature more remarkable than the fact of a fish being able to shoot a fly with a drop of water projected through its tubular beak, if we may use that expression for so curiously modified a mouth.

Indeed, so certain is the fish of its aim, that in Japan it is kept as a pet in glass vases, just as we keep gold fish in England, and is fed by holding flies or other insects to it on the end of a rod a few inches above the surface of the water. The fish is sure to see the insect, and equally sure to bring it down with a drop of water propelled through its beak.

It is worthy of remark that the same principle was once, though unsuccessfully, employed in the propulsion of carriages, under the name of the Pneumatic Railway. Some of my readers may remember the railway itself, or at all events the disused tubes which lay for so many years along the Croydon Railway. Speed was obtained, as I can testify from personal experience, but the expense of air-pumps and air-tight tubing was too great to be covered by the income, especially as the rats ate the oiled leather which covered the valves.

I find some little difficulty in arranging the subject which comes next in order. It might very properly be ranked among the Levers, which will be treated of in another chapter; or it might be placed among the examples of centrifugal force, together with the sling, the “governor” of the steam-engine, &c., all of which will be more fully described in their places. However, as we are on the subject of Projectiles, we may as well take it in the present place.

It is the Throwing-stick, by which the power of the human arm is enormously increased, when a spear is to be hurled. Perhaps the most expert spear-throwers in the world are to be found among the Kafir tribes of Southern Africa, and yet the most experienced among them could not make sure of hitting a man at any distance above thirty or forty yards. But the throwing-stick gives nearly double the range, and I have seen the comparatively slight and feeble Australian hurl a spear to a distance of a hundred yards, and with an aim as perfect as that of a Kafir at one-fourth of the distance.

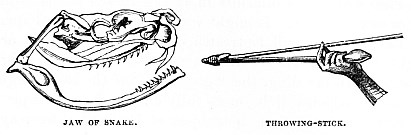

The mode in which this feat is performed is shown in the accompanying diagram. Instead of holding the spear itself, the native furnishes himself with a “Throwing-stick.” This weapon varies greatly in shape and size, but a very good idea of its form, and the manner of using it, may be obtained from the accompanying illustration, which was drawn from the actual specimen as held by an Australian native.

The throwing-stick is armed at the tip with a short spike, which fits into a little hole in the but of the spear. The stick and spear being then held as shown in the illustration, it is evident that a powerful leverage is obtained, varying according to the length of the stick. I possess several of these instruments, no two of which are alike.

It is rather remarkable that among the Esquimaux a throwing-stick is also used, exactly similar in principle, but differing slightly in structure, the but of the spear fitting into a hole at the end of the throwing-stick. Wood being scarce among the Esquimaux, these instruments are mostly made of bone. I possess one, however, which is made of wood, beautifully polished, and adorned with a large blue stone, something like a turquoise, set almost in its middle. One of the most curious points in the formation of the Esquimaux weapon is, that the but is grooved and channelled so as to admit the fingers and thumb of the right hand. The average length of this instrument is twenty inches.

In New Caledonia the natives use a contrivance for increasing the power of the spear, which is based on exactly identical principles, though the mode of carrying them out is different. A thong or cord of some eighteen inches in length is kept in the right hand, one end being looped over the forefinger, and the other, which is terminated by a button, being twisted round the shaft of the spear. When the weapon is thrown, the additional leverage gives it great power; and it is a noteworthy fact that the sling-spear of New Caledonia has enabled us to understand the otherwise unintelligible “amentum” of the ancient classic writers.

Passing from Art to Nature, we have in the jaw of the serpent an exact type of the peculiar leverage by which the spear is thrown. If the reader will refer to the illustration, he will see that the lower jaw of the snake, instead of being set directly on the upper jaw, is attached to an elongated bone, which gives the additional leverage which is needful in the act of swallowing prey, after the manner of serpents.

In War and in Peace we have been long accustomed to shield the edges and points of our sharp weapons with sheaths, and even the very savages have been driven to this device. I have in my collection a number of sheathed weapons from nearly all parts of the world, and it is a remarkable fact that the Fan tribe, who are themselves absolutely naked, sheathe their daggers and axes as carefully as we sheathe our swords and bayonets. In some points, indeed, they go beyond us; for the most ignorant Fan savage would never think of blunting the edge of his weapon by sheathing it in a metal scabbard. Their sheaths are beautifully made of two flat pieces of wood, just sufficiently hollowed to allow the blade to lie between them, and bound together with various substances. For example, the sheaths of one or two daggers in my possession are made of wood covered with snake-skin, while others are simply wood bound with a sort of rattan. Even the curious missile-axe which the Fan warrior uses with such power is covered with a sheath when not in actual use.

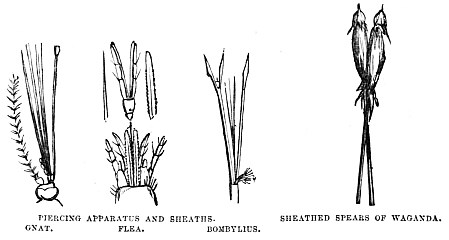

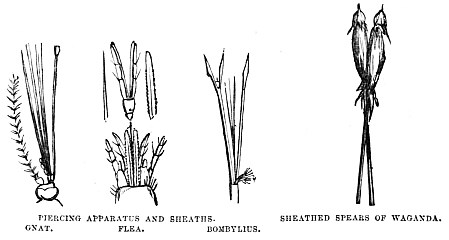

The figure on the right hand of the illustration represents the heads of two spears of Waganda warriors. When they present themselves before their king, the warriors must not appear without their weapons, and it would be contrary to all etiquette to show a bare blade except in action. The sheath can be slipped off in a moment, but there it is, and any man who dared to appear before his sovereign without his weapon, or with an unsheathed spear, would lose his life on the spot, so exact is the code of etiquette among these savages.

The sheathed spears of Nature are shown in the same illustration. On the left is a side view of the piercing apparatus of the common Gnat.

In the middle is the compound piercing apparatus of the common Flea, with which we are sometimes too well acquainted, the upper figure showing the lancets and sheaths together, and the lower exhibiting them when separated.

On the right is shown the group of mouth-lancets belonging to one of the Humble-bee flies (Bombylius). These flies do not suck blood like the Mosquito, the Flea, and the Gad-fly, but they use the long proboscis for sucking the sweet juices out of flowers, and in consequence it is nearly of the same form as if it were meant for sucking blood. Indeed, there are some insects which do not seem to care very much whether the juice which they suck is animal or vegetable.

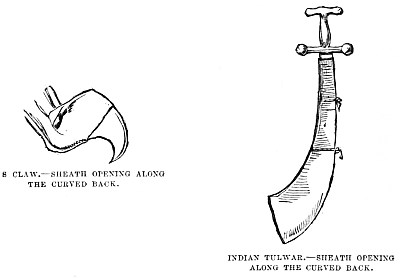

On the right hand of the illustration is seen an Indian sword, or “Tulwar,” drawn from one of my own specimens. I have selected this example on account of the structure of the sheath. It is evident, from the form of the blade, that the sword cannot be sheathed point foremost, and that therefore some other plan must be used. In this weapon the sheath is left open on one side, the two portions being held together by the straps which are shown in the figure. Of course there is loss of time in sheathing and drawing such a sword, but the peculiar shape of the blade entails a necessity for a special scabbard.

On the other side is shown one of the fore-claws of a cat, which, as we all know, can be drawn back into its simple sheath between the toes, when it is not in use. This sheath is exactly the same in principle as that of the Indian tulwar, and any one can examine it by looking at the foot of a good-tempered cat. I have done so even with a chetah, which is not a subject that would generally be chosen for such a purpose.

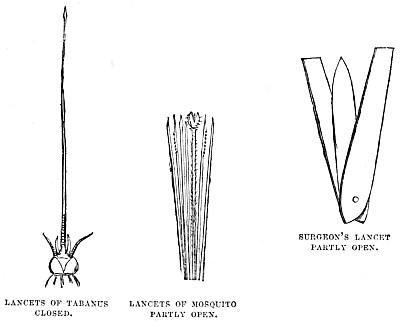

On the next illustration is shown an ordinary Lancet, in which the blade is guarded between a double sheath, the two halves and the blade itself working upon a common pivot. As for the ordinary sword and dagger sheaths, it is not worth while to figure them.

Turning to the opposite side of the illustration, we shall see a few of the innumerable examples in which the principle of the sheath was carried out in Nature long before man came on the earth.

The reader should compare this figure with the side view of the Gnat’s lancets given on p. 81.

They represent the cutting and piercing instruments of several insects, all of which are very complicated, and are sheathed after the manner of the lancet. Indeed, they are popularly known as “mouth-lancets,” and with reason, as the reader may see by reference to the illustration.

On the extreme left are shown the head and closed lancets of a foreign Gad-fly, the lancets being all in their sheaths, and showing the character of the weapon which enables a small fly to be master, or rather mistress, of the forest. I say mistress, because in all these cases it is the female alone that possesses these instruments of torture.

Next it is a magnified representation of the lancets of the common Mosquito, as seen from above, both lancets being removed from their sheaths and separated.

CHAPTER IV

The Net, as used in Hunting and War.—The Seine-net, as used for Fishing.—Also as a means of Hunting.—Net for Elephant-catching.—Steel Net for Military Purposes.—Web of the Garden Spider.—The Casting-net, as used in Fishing.—Also as employed in the Combats of the ancient Circus.—Various Kinds of Casting-nets.—The Argus Star-fish and the Barnacle.—The Rod and Line.—Angling of various Kinds.—The Polynesian as an Angler.—The Angler-fish.—“Playing” a Fish.—The Nemertes and its Mode of Feeding.—Mr. Kingsley’s Account of it.—Power of Elongation and Contraction.—The Cydippe.—Spring-traps.—The Gin, Rat-trap, and Man-trap.—Jaws of Dolphin, Porpoise, and Alligator.—Legs of Phasma.—Baited Traps.—Carnivorous Plants and their Mode of Feeding.—Birdlime.—“Pegging” for Chaffinches.—Curious Mode of Tiger-killing.—Ant-eater and its Mode of Feeding.—The Drosera.—Web of Spider and its Structure.

The NetALTHOUGH the Net is but seldom employed for the purposes of general warfare, it was once largely used in individual combats, of which we will presently treat. In hunting, however, especially in fishing, the Net has been in constant use, and is equally valued by savages and the most civilised nations.

To begin with the fisheries. Even among ourselves there are so many varieties of fishing-nets that even to enumerate them would be a work of time. However, they are all based on one of two principles, i.e. the nets which are set and the nets which are thrown.

We will begin with the first.

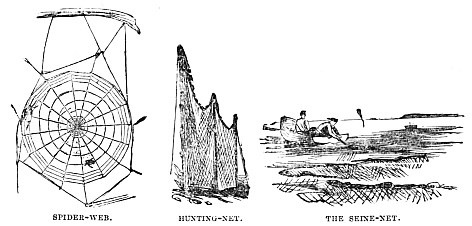

On the right hand of the illustration, and at the bottom, may be seen a common Seine-net being “shot” in the sea. This form of net is very long in proportion to its width, some of these nets being several miles long. The upper edge of the net is furnished with a series of cork bungs, which maintain it on the surface, while the lower edge has a corresponding set of weights, which keep the net extended like a wall of meshes. Any fish which come against this wall are, of course, arrested, and are generally caught by the gill-covers in their vain attempts to force themselves through the meshes.

We may see representations of fishing with the seine-net in the sculptures and paintings of Egypt and Assyria; and in the Berlin Museum there is a part of an Egyptian seine-net with the leads still upon the lower edge, and the upper edge bearing a number of large pieces of wood, which acted as buoys, and served the same purpose as our corks.

In hunting, this plan has been adopted for many centuries, the upper edge of the net being supported on poles, and the lower fastened to the ground in such a manner as to leave the net hanging in loose folds. While this part of the business is being completed by the servants, the hunters are forming a large semicircle, in which they enclose a number of wild beasts, which they drive into the nets or “toils” by gradually contracting the semicircle. The ancient sculptures give us accounts of nets used in exactly this manner. There are represented the nets rolled up ready for use, and being carried on the shoulders of several attendants, who are bearing them to the field. Then there are the nets set up on their poles, and having enclosed within them a number of wild animals, such as boars and deer.

In various parts of India, hunting with the net is one of the chief amusements of their principal men, and the variety of game driven into the toils is really surprising, and affords a magnificent sight to those who view it for the first time. Even the tiger himself cannot leap over the nets because they are so high, nor force his way through them, because their folds hang so lightly that they offer no resistance to his efforts.

A very simple net on similar principles is used for catching elephants. It is formed of the long creeping plants that fling themselves in tangled masses from tree to tree. These creepers are carefully twisted into a net-like form, without being removed from the trees, and when a sufficient space has been enclosed the elephants are driven into it. Not even their gigantic strength and tons of weight are capable of breaking through a barrier which, apparently slight, is as strong as if it were built of the tree-trunks on which the creepers are hung.

This net is seldom used for military purposes, though I have seen one, which I believe still exists, and would do good service. In one of our largest fortresses there is a subterranean corridor, through which it is desirous that the enemy should not penetrate. One mode of defence consists of a large net made of steel hanging loosely across it. The meshes are about ten inches square, so that the defenders can fire from their loopholes through the meshes, while the assailants, even if they knew of its position, would find that nothing smaller than a field-gun would have any effect on this formidable net.

The natural analogy of the fixed net is evidently the web of the common Garden Spider, or Cross Spider (Epeira diadema), whose beautiful nets we all must have admired, especially when we are wise enough to get up sufficiently early in the morning to see the webs with the dewdrops glittering on them.

Last year there was a wonderful sight. Within a mile of my house there is a long iron fence, which in one night had been covered with the webs of the garden spider. The following morning, though bright, was chilly, so that the dewdrops were untouched. I happened to pass by the fence soon after sunrise, and was greatly struck with the astonishing effects which could be produced with such simple materials as water and web. The dewdrops were set at regular intervals upon the web, so as to produce a definite and beautiful pattern, the whole line of fence looking as if it had been woven in fine lace.

Then, as the fence runs north and south, and the path is on the westward of it, every passenger saw the rays of the rising sun dart through these tiny globules, and convert every one of them into a jewel of ever-changing colours. It seemed a pity that such beauty could but last for an hour or so, or that these exquisite webs should only be used for catching flies.

Next comes the Casting-net in its various forms. This net is mostly circular, and is loaded round the edge with small leaden plummets. It is evident that, if such a net could be laid quite flat upon the water, it would assume a dome-like shape, in consequence of the circumference being heavier than the centre, and would sink to the bottom, enclosing anything which came within its scope.

The difficulty is to place the net in such a manner, and this is accomplished by throwing it in a very peculiar way. The net is gathered in folds upon the shoulder, which it partially envelops. By a sudden jerk the thrower causes it to fly open with a sort of spinning movement, and when well cast it will fall on the water perfectly flat.

After allowing it to sink to the bottom, the fisherman draws it very gently by a cord attached to its middle. As he raises it the weights of the leaded circumference are drawn nearer and nearer together by their own weight, and finally form it into a bag, within which are all the living creatures which it has enclosed.

Though the Casting-net has never been used in warfare, it was one of the favourite implements in gladiatorial combats among the Romans. Two men were opposed to each other; one, called the Retiarius or Netsman, being quite naked, except sometimes a slight covering round the waist, and armed with nothing but a Casting-net and a slight trident, which could not inflict a deadly wound. The other, called the Secutor or Follower, from his mode of fighting, was armed with a visored helmet, a broad metal belt, and armour for the legs and arms. He also carried a shield large enough to protect the upper part of the body, and a sword. It will be seen, therefore, how great was the power of the Casting-net, when it enabled its naked bearer to face such odds of offensive and defensive armour.

When the two met in combat, the Retiarius tried to fling his net over his adversary, and if he succeeded, the fate of the latter was sealed. Entangled in the loose meshes, he could scarcely move his limbs, while the sharp prongs of the long-shafted trident came darting in at every exposed point, and exhausting the man with pain and loss of blood. The trident was in itself so feeble a weapon, that if the Secutor were vanquished and condemned to death by the spectators, his antagonist could not kill him, but had to call another Secutor to act as executioner with his sword.

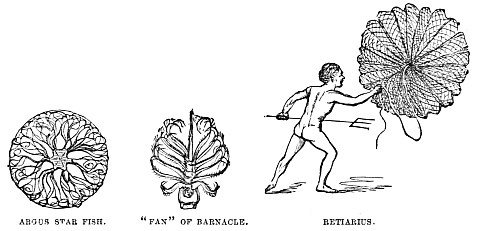

Should he fail in his cast, the Retiarius drew back his net by the central cord, and took to flight, followed by the Secutor, who tried to wound him before he could re-fold his net upon his shoulder, ready for another cast. It is worthy of notice that in these singular combats the netsman seems generally to have been the victor. A Retiarius with his net is shown in the illustration.

I may mention that our ordinary bird-catchers’ nets, and even the entomologist’s insect-net, are only modifications of the Casting-net.

Now for Nature’s Casting-nets, two examples of which are figured, though there are many more. These two have been selected because they are familiar to all naturalists.

The first is the Argus Star-fish, Basket-urchin, or Sea-basket. The innumerable rays and their subdivisions, amounting to some eighty thousand in number, act as the meshes of the net. All the rays are flexible and under control. When the creature wishes to catch any animal for prey, it throws its tentacles over it, just like the meshes of a net. It then draws the tips of the rays together, just as is done by the circumference of the casting-net, and so encloses its prey effectually.

The next specimen is the net-like apparatus of the common Acorn Barnacles, with which our marine rocks are nearly covered. These curious beings belong to the Crustacea, and the apparatus which is figured on page 89, and popularly called the “fan,” is, in fact, a combination of the legs and their appendages of bristles, &c. When the creature is living and covered with water, the fan is thrust out of the top of the shell, expanded as far as possible, swept through the water, closed, and then drawn back again. With these natural casting-nets the Barnacles feed themselves, for, being fixed to the rock, they could not in any other way supply themselves with food. There are many similar examples in Nature, but these will suffice.

The Rod and LineThat both terrestrial and aquatic nets should have their parallels in Nature is clear enough to all who have ever seen a spider’s web, or watched the “fan” of the barnacle. But that the rod and baited line, as well as the net, should have existed in Nature long before man came on earth, is not so well known. Yet, as we shall presently see, not only is the bait represented in Nature, but even our inventions for “playing” a powerful fish are actually surpassed.

We will begin with the Bait.

In nearly all traps a bait of some kind is required, in order to attract the prey, and when we come from land to attract the dwellers in water to our hooks, it is needful that bait of some kind should be used, were it only to deceive the eye, though not the nostrils or palate, of the fish.

A notable example of the deception is given in the common artificial baits of the present day, which are made to imitate almost any British insect which a fish might be disposed to eat.

Perhaps the best instance of this deception is that which is practised by sundry Polynesian tribes. They have seen that the Coryphene or Dorado, and other similar fish, are in the habit of preying upon the flying-fish, and springing at them when they are tolerably high in the air. So these ingenious semi-savages dress up a hook made of bone, ormer-shell, and other materials, making the body of it into a rudely designed form of a fish. A hole is bored transversely through it at the shoulders, and a bunch of stiff fibres is inserted to represent the wings. Another bunch does duty for the tail.

The imitation bait being thus complete, it is hung to a long and slender bamboo rod, which projects well beyond the stern of a canoe, and is so arranged that the hook is about two feet or so from the surface. The Coryphene, seeing this object skimming along, takes it for a flying-fish, leaps at it, and is caught by the hook. There are in several collections specimens of these ingenious hooks, and I possess one which is made on similar principles, but intended for use in the water, and not in the air. It is, in fact, a “spoon-bait.”