полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

On the left hand of the illustration is the section of a pitfall made by the well-known Ant-lion (Myrmeleo), of which there are several species. The history of this wonderful insect is so familiar to us that it need not be repeated at length. Suffice it to say that it digs conical pitfalls in loose sandy soil, and that it places itself at the bottom of the pit, securing the insect victims with its jaws just as the larger animals are secured by the stake of the human hunter.

It makes no false cover, as does the human hunter, but it always chooses soil so loose that if an insect approach the edge, the sand gives way, and it goes sliding down into the pit, whence its chance of escape is very small, even were there no deadly jaws at the bottom ready to receive it.

The ClubThe simplest of all offensive weapons is necessarily the Club. At first, this was but a simple stick, such as any savage might form from a branch of a tree by knocking off the small boughs with a stone or another stick. Such clubs are still used in Australia, and I have several in my collection.

Then the inventive genius of man improved their destructive power by various means. The most obvious plan was to add to the force of its blow by simply making one end much thicker and heavier than the other. This is done in the “Knob-kerry” of Southern Africa, and it is worthy of remark that in Fiji a weapon exists so exactly like the short knob-kerry of Africa, that an inexperienced eye would scarcely be able to distinguish between them.

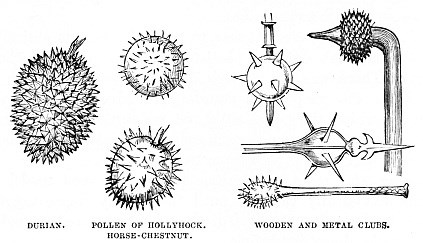

The next plan was to arm the enlarged head with projecting pieces or spikes, sometimes cut out of the solid wood, and sometimes artificially inserted. The “Shillelagh” of Ireland is a simple example of this kind of club. One of the best and most elaborate examples of this sort of weapon is the “Pine-apple” Club of Fiji, a figure of which may be seen in the illustration, drawn from a specimen in my collection.

It is made in the most ingenious manner from a tree which is trained for the purpose. There are certain trees belonging to the palm tribe which possess “aërial” roots, i.e. subsidiary roots, which surround the trunk at some distance from the ground, and assist in supporting it. Some trees have no central root, and are entirely upborne by the aërial roots, while others have both.

One of these latter is selected, and when it is very young is bent over and fastened to the ground almost at right angles, as shown in the illustration. When it has grown to a sufficient age it is cut to the requisite length, the central root is sharpened to a point, and the aërial roots are also cut down in such a way that they radiate very much like the projections on a pine-apple. This is really an ingenious weapon, for if the long and sharpened end should miss its aim, the projections would be tolerably sure to inflict painful if not immediately dangerous injuries.

As the pine-apple is so well known, I have given in the opposite side of the illustration a figure of the Durian, a large Bornean fruit, which is covered with projections almost identical in appearance with those of the pine-apple club, and almost equally hard and heavy.

Perhaps some of my readers may have heard of the grand Italian game of Pallone, the “game of giants,” as it has been called. The ball, which is a large and rather heavy one, weighing more than twice as much as a cricket-ball, is struck with a wooden gauntlet reaching nearly half-way up the fore-arm. The original gauntlet was cut entirely out of the solid wood, and exactly resembled the exterior of the Durian. The modern gauntlet, however, has the spikes fixed separately into a wooden frame, so that they can be replaced if broken in the course of the game. The principle, however, is identical in all three cases. The technical name of this gauntlet is Bracciale.

The next improvement was to add still further to the destructive powers of the club by arming it with stones, so as to make it harder and heavier. Sometimes a stone is perforated, and the end of the club forced into it. Sometimes the stone is lashed to the club, and sometimes a hole is bored in the club, and the stone driven into it. This kind of club, made of a sort of rosewood, may be found among some of the tribes inhabiting the district of the Essequibo.

The next improvement was to make the weapon entirely of metal, and such clubs are plentiful in every good collection of arms. There was, for example, the common mace, which was used for the purpose of stunning an adversary clothed in armour which the sword could not penetrate. As this, however, was nothing more than an ordinary wooden club executed in iron, we need not produce examples.

Other and more complicated forms were soon made, and were wonderfully valuable until the rapidly improving firearms kept combatants at a distance, and rendered a hand-to-hand fight almost impossible.

Three examples of such clubs are given in the illustration, and are taken from Demmin’s valuable work called “Weapons of War.”

The upper left-hand specimen is called Morgenstern, i.e. Morning Star. It is a large, heavy wooden ball studded with steel spikes, and affixed to a handle usually some six or seven feet, but sometimes exceeding eleven feet, in length. It was chiefly used by infantry when attacking cavalry, the long shaft enabling the foot-soldier to be tolerably sure of dealing the cavalier or his horse a severe blow, while himself out of reach of the latter’s sword.

Behind it is another Morgenstern in which there is an improvement, the armed ball being furnished at the end with a spike, so that it could be used either as a mace or a spear.

The commonest form of the Morning Star is shown below, and is thus described by Demmin:—

“This mace had generally a long handle, and its head bristled with wooden or iron points. It was common among the ancients, for many museums possess several fragments of these weapons belonging to the age of bronze.

“The Morning Star was very well known and much used in Germany and Switzerland. It received its name from the ominous jest of wishing the enemy ‘good morning’ with the Morning Star when they had been surprised in camp or city.

“This weapon became very popular on account of the facility and quickness with which it could be manufactured. The peasants made it easily with the trunk of a small shrub and a handful of large nails. It was also in great request during the wars of the peasantry which have devastated Germany at different times, and the Swiss arsenals possess great numbers of them.”

One of these primitive weapons may be seen in the lower figure of the illustration.

Sometimes the spiked ball was attached to a chain, and fastened to the end of a handle varying greatly in length, measuring from two to ten feet. One of these weapons may be seen in the Guildhall of London, being held by one of the celebrated giants.

If the reader will now turn to the illustration on page 53, he will see that on the right of the Durian there are two spherical objects covered with spikes. The upper is the pollen of the Hollyhock, and the lower the common Horse-chestnut. The reader will see that these are precisely similar in form to the spiked balls of the Morgenstern, whether they be used at the end of a staff or slung to a chain. There are many similar examples in the vegetable kingdom which will doubtless suggest themselves to the reader, but these are amply sufficient for this purpose.

Then, in the animal world, the curious Diodons, sometimes called Urchin-fishes, or Prickly Globe-fishes, are good examples. These fishes are covered with sharp spines, and, as they have the power of swelling their bodies into a globular form, the spikes project on all sides just like those of the pollen or chestnut. There is a specimen in my collection, which, if the tail and fins were removed, and a cast taken in metal, would make a very good Morgenstern ball.

The SwordThe next improvement on the club was evidently to flatten it, and sharpen one or both edges, so as to make it a cutting as well as a stunning implement—in fact, the club was changed into a Sword.

A good example of this weapon in its simplest form is the wooden sword of Australia, now an exceedingly rare weapon. It looks like a very large boomerang, but is nearly straight, and is made from the hard, tough wood of the gum-tree. Travellers say that the natives can cut off a man’s head with this very simple weapon.

I just missed obtaining one of these swords from a man-of-war, but, unfortunately, a few hours before my arrival the zealous first lieutenant had ordered a large collection of savage weapons to be thrown overboard, among which were several Australian swords.

Finding that the edges were not sufficiently sharp, and were liable to break, the maker next turned his attention to arming them with some substance harder than wood. Various materials were used for this purpose, some of which will be mentioned.

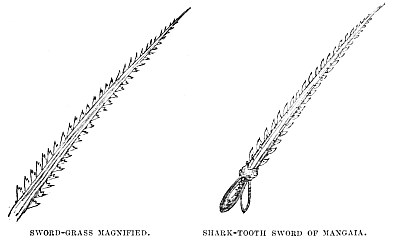

One of these is given in the illustration, and is taken from a specimen in my collection. It is made of wood, rather more than two feet in length, and would in itself be an insignificant weapon but for its armature.

This consists of a number of sharks’ teeth, which are fixed along either side, and are a most formidable apparatus, each tooth cutting like a lancet-blade, and not only being very sharp, but having their edges finely notched like the teeth of a saw. I have a series of these weapons in my collection, some being curved, some straight, and one very remarkable weapon having four blades, one straight and long blade in the centre, and three curved and short blades springing from the handle towards the point.

Opposite the shark-tooth sword is an object which might almost be taken for a similar weapon, but is, in fact, nothing but a common grass-blade, such as may be found in any of our lanes. I suppose that most of my readers must at some time have cut their fingers with grass, and the reason why is shown in the illustration, which represents a much-magnified blade of grass. The edges of the leaf are armed with sharp teeth of flint, set exactly like those of the sword, with their points directed towards the tip of the blade. The whole of the under surface of the blade is thickly set with similar but smaller teeth, arranged in the same manner. I have just brought a blade of grass from a lane near my house, and when it was placed under the half-inch power of the microscope, the resemblance to the sword was absolutely startling to some spectators who came to look at it.

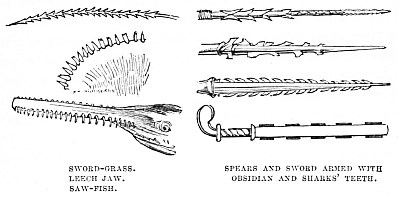

As if to make the resemblance closer, many savage weapons are edged with flat stones, flint chips, or pieces of obsidian, so that the flint teeth of the grass are exactly copied by the flint edgings of the sword. The old Mexican swords were nearly all edged with obsidian, as is seen in the lower right-hand figure of the next illustration. I possess a number of obsidian flakes which were intended for that purpose, but do not appear to have been used.

The second figure from the top represents the head of a spear similarly armed, and I possess a small Australian implement in which the flakes of obsidian are set only on one side, so that the instrument can be used as a rude saw.

Between these two weapons is a spear-head armed with shark-teeth. I have a very remarkable weapon of this kind, made in Mangaia. It is eleven feet in length, and, besides being armed with a double row of sharks’ teeth nearly to the handle, it has three curved blades similarly armed, set at distances of about two feet, and projecting at right angles. Thus, if the foe were missed with the point of the spear, he would probably be wounded by one of the blades.

The upper figure represents a weapon where the natural bone of the sting-ray has been used as the point.

On the opposite side are seen three natural objects similarly armed. The uppermost is another species of sword-grass, like that which has already been described.

Next comes a magnified view of one of the three cutting instruments of the leech, showing the serrated teeth set along its edge, by means of which it produces the sharply-cut wounds through which it sucks the blood.

The last figure represents the head of the common Saw-fish, in which a vast number of flat and sharply-edged teeth are set upon the blade-like head. The fish has been observed to use this weapon just as the Mangaian uses his sword-spear. It dashes among a shoal of fish, sweeps its head violently backwards and forwards, and then, after they have dispersed, picks up at its leisure the dead and disabled.

The Spear and the DaggerIt is tolerably evident that the invention of the spear and dagger must have been nearly, if not quite, contemporaneous with that of the club. I place these weapons together because there is great difficulty in assigning to either of them the precedence, the spear being but a more or less elongated dagger, and the dagger a shortened spear.

As a good example of this fact, I have in my collection a number of spears and daggers belonging to the Fan tribe of Western Africa. In every case the weapons correspond so closely with each other, that if the daggers were attached to shafts they would exactly resemble the spears, and if the spears were cut off within a few inches of the head, they would be taken for daggers.

I may here mention that as this part of the subject merely involves the employment of a pointed or thrusting weapon, instead of the club or sword, both of which are used for striking, the question of poison, barbs, and sheaths will be treated on another page.

The primary origin of the Spear is probably the thorn, as a savage who had been wounded by a thorn would easily pass to the conclusion that a thorn of larger size would enable him to kill an enemy in war, or an animal in hunting. Anything of sufficient dimensions, which either possessed a natural point or could be sharpened into a point, would be available for the purpose of the hunter or warrior.

Accordingly we find that such objects as the beak of the heron or stork, the sharp hind-claw of the kangaroo, the bone of the sting-ray, the beak of the sword-fish, and many similar objects, are employed for the heads of spears, or used simply as daggers.

As to artificial spears, nothing is easier than to scrape a stick to a point, and then, if needful, to harden it in the fire. This is, indeed, one of the commonest forms of primitive spears, and I have in my collection many examples of such weapons. Another simple form of this weapon is that which is made by cutting a stick or similar object diagonally.

Hollow rods—such, for example, as the bamboo—are the best for this purpose. I have now before me a cast of a most interesting weapon discovered by Colonel Lane Fox. It is the head of a spear, and is formed from part of the leg-bone of a sheep. At one end there is a simple round hole, which acted as a socket for the reception of the shaft, and the other end is cut away diagonally, so as to leave a tolerably sharp point.

As to the bamboo, it has a great advantage in the thinness of its walls, and the coating of flinty substance with which it is surrounded, and which gives its edges a knife-like sharpness. Indeed, so very sharp is the silex, that splinters of bamboo are still used as knives, and with them a skilful operator can cut up a large hog as expeditiously as one of our pork-butchers could do with the best knife that Sheffield produces.

I possess several of these weapons, and formidable arms of offence they are. If the reader can imagine to himself a toothpick, a foot or more in length, made from bamboo instead of quill, and having its edges nearly as sharp as a razor, he can realise the force of even so simple a weapon. In the case of the bamboo, too, celerity of manufacture has its value, for any one can make a couple of spears in less than as many minutes. All he has to do is to cut down a joint of bamboo transversely, and then with a diagonal blow of his knife at the other end to form the point.

The force of such a weapon may be inferred from a remarkable combat that took place some sixty years ago, when the roads were not so safe as they are at present.

A gentleman, who happened to be a consummate master of the sword, was going along the highway at night, and was attacked by two footpads, he having no weapon but a bamboo cane.

One of them he temporarily disabled by a severe kick, and then turned to the other, whom he found to be pretty well as good a swordsman as himself, and to possess a good stick instead of a slight cane. The footpad soon discovered the discrepancy of weapons, and with a sharp blow smashed the cane to pieces, leaving only about eighteen inches in his antagonist’s hand.

Almost instinctively Baron – sprang under the man’s guard, and dashed the broken cane in his face. The footpad staggered with a groan, put his hands to his face, and ran away, followed by his companion, who did not desire another encounter with such an antagonist. When the victor reached his destination, he found that the footpad’s face must have been torn to pieces, for the clefts of the split bamboo were full of scraps of skin, flesh, and whisker hair.

It is worthy of notice that the combination of the club and the dagger is common to savage and civilised life, as may be seen by reference to the illustration in page 53, where the wooden club of savage warfare and the metal club and maces of civilisation are alike armed with a piercing as well as a bruising apparatus. Mostly the dagger is on the head of the mace or battle-axe, but, in some cases, the end of the handle acts as the dagger, and the head as the axe or mace.

A very good example of this formation is found in the wooden battle-axe, or “Patoo,” of New Zealand, a weapon which has been long superseded by modern fire-arms. A specimen in my possession is rather more than five feet in length. The head is just like that of an ordinary axe, while the handle tapers gradually to the end, where it terminates in a sharp spike. In actual combat the point was used much more than the axe.

CHAPTER II.

POISON, ANIMAL AND VEGETABLE.—PRINCIPLE OF THE BARB

Poison as applied to Weapons.—Its limited Use.—Animal and Vegetable Poisons.—Animal Poisons.—The Malayan Dagger, or Kris, and two Modes of poisoning it.—The Bosjesmans and their Arrows.—Snake Poison and its Preparation.—The Pseudo-barb.—The Poison-grub, or N’gwa.—Simple Mode of Preparation, and its terrible Effects.—Vegetable Poisons.—The Upas of Malacca.—The Wourali Poison of Tropical America.—Mode of preparing the various Arrows.—The Fan Tribe of West Africa, and their poisoned Arrows.—Subcutaneous Injection.—Examples in Nature.—The Poison-fang of the Serpent.—Sting of the Bee.—Tail of the Scorpion.—Fang of the Spider.—Sting of the Nettle.—Exotic Nettles and their Effects.—The Barb and its Developments.—The “Bunday” of Java.—Reversed Barbs of Western Africa.—Tongans and their Spears.—The Harpoon and Lernentoma, or Sprat-sucker.—The Main Gauche, or Brise-épée.

ANOTHER advance, if it may so be called, lay in increasing the deadly effect of the weapons by arming them with poison.

Without the poison, it was necessary to inflict wounds which in themselves were mortal; but with it a comparatively slight wound would suffice for death, providing only that the poison mixes with the blood. It is worthy of notice that cutting weapons, such as swords and axes, seldom, if ever, have been envenomed, the poison being reserved for piercing weapons, such as the dagger, the spear, and the arrow.

Animal PoisonsPerhaps the most diabolical invention of this kind was the Venetian stiletto, made of glass. It came to a very sharp point, and was hollow, the tube containing a liquid poison. When the dagger was used, it was driven into the body of the victim, and then snapped off in the wound, so that the poison was able to have its full effect.

Such poisons are of different kinds, and invariably animal or vegetable in their origin. Taking the animal poisons first, we come to the curious mode of poisoning the Malayan dagger, or “Kris.” The blade of the weapon is not smooth, but is forged from very fibrous steel, and then laid in strong acid until it is covered with multitudinous grooves, some of them being often so deep that the acid has eaten its way completely through the blade.

Among some tribes the kris is poisoned by being thrust into a putrefying human body, and allowed to remain there until the grooves are filled with the decaying matter. It is also said that if the kris be similarly plunged into the thick stem that grows just at the base of the pine-apple, the result is nearly the same.

As a rule, however, the Arrow is generally the weapon which is poisoned, and a few examples will be mentioned of each kind of poisoning.

The two most formidable animal poisons are those which are made by the Bosjesmans of Southern Africa. Their bows are but toys, and their arrows only slender reeds. But they arm these apparently insignificant weapons with poison so potent, that even the brave and bellicose Kafir warrior does not like to fight a Bosjesman, though he be protected by his enormous shield.

There are two kinds of animal poison used by the Bosjesmans. The first is made from the secretion of the poison-glands of the cobra, puff-adder, and cerastes. Knowing the sluggish nature of snakes in general, the Bosjesman kills them in a very simple manner. He steals cautiously towards the serpent, boldly sets his foot upon its neck, and cuts off its head. The body makes a dainty feast for him, and the head is soon opened, and the poison-glands removed.

By itself, the poison would not adhere to the point of the weapon, and so it is mixed with the gummy juice of certain euphorbias, until it attains a pitch-like consistency. It is then laid thickly upon the bone point of the arrow, and a little strip of quill is stuck into it like a barb. The object of the quill is, that if a man, or even an animal, be wounded, and the arrow torn away, the quill remains in the wound, retaining sufficient poison to insure death. I have a quiverful of such arrows in my collection.

That arrows so armed should be very terrible weapons is easily to be imagined, but there is another kind of poison which is even more to be dreaded. This is procured from the innocent-looking, but most venomous, Poison-grub. It is called N’gwa by the Bosjesmans, and is the larval state of a small beetle. When the arrow is to be poisoned, the grub is broken in half, and the juices squeezed upon the arrow in small spots.

Both Livingstone and Baines give full and graphic accounts of the horrible effect produced by this dread poison, which, as soon as it mixes with the blood, drives the victim into raging madness. A lion wounded by one of these arrows has been known nearly to tear himself to pieces in his agonies. M. Baines was good enough to present me with the N’gwa grub in its different stages, together with an arrow which has been poisoned with its juices.

The Bosjesmans are themselves so afraid of the weapon, that they always carry the arrows with the points reversed, the poisoned end being thrust into the hollow reed which forms the shaft of the arrow. Not until the arrow is to be discharged does its owner place the tip with its point uncovered.

Vegetable PoisonsWe now come to the Vegetable Poisons, the two best known of which are the Upas poison of Borneo, and the Wourali of South America. It is rather remarkable that in both these cases the arrows are very small, and are blown through a hollow tube, after the manner of the well-known “Puff-and-dart” toy of the present day.

The Upas poison is simply the juice of the tree, and it does not retain its strength for more than a few hours after it has been placed on the arrow-points. A supply of the same liquid is therefore kept in an air-tight vessel made of bamboo, the opening being closed by a large lump of wax kneaded over it at the mouth. One of these little flasks, taken from a specimen in my collection, is seen on the extreme right of the illustration.

The Wourali poison owes all its power to its vegetable element, though certain animal substances are generally mixed with it. The principal ingredient is the juice of one of the strychnine vines, which is extracted by boiling, and then carefully inspissated until it is about the consistency of treacle. This poison differs from the Upas in the fact that it retains its potency after very many years, if only kept dry. I have a number of arrows poisoned with the Wourali. They were given to me by the late Mr. Waterton, who procured them in 1812, and even in the present year (1875) they are as deadly as when they were first made.