полная версия

полная версияNature's Teachings

The female flowers are attached to a very long spiral and closely coiled footstalk, and, when they are sufficiently developed, the footstalk elongates itself until the flower rests on the surface of the water, where it is safely anchored by its spiral cable, the coils yielding to the wavelets, and keeping the flower in its place.

Meanwhile the tiny male flowers are being developed at the bottom of the river, and are attached to very short footstalks. When they are quite ripe they disengage themselves from their footstalks, and rise to the surface of the river. Being carried along by the stream, they are sure to come in contact with the anchored female flowers. This having been done, and the seeds beginning to be developed, the spiral footstalk again coils itself tightly, and brings the seeds close to the bed of the stream, where they can take root.

There are other numerous examples, of which any reader, even slightly skilled in botany, need not be reminded, most of them being, in one form or another, modifications of the leaf or the petal, which, after all, are much the same thing. The vine and passion-flower are, however, partial exceptions.

I may here mention that soon after the failure of the first Atlantic telegraph cable, an invention was patented of a very much lighter cable, enclosed in a tube of india-rubber, and being coiled spirally at certain distances, so that the coils might give the elasticity which constitutes strength. The cable was never made, its manufacture proving to be too costly; but the idea of lightness and elasticity, having been evidently taken from the spiral tendrils of the bryony, was certainly a good one, and I should have wished to see it tried on a smaller scale than the Atlantic requires.

As a natural consequence, after the cable comes the Anchor, which in almost every form has been anticipated by Nature, whether it be called by the name of anchor, kedge, drag, or grapnel.

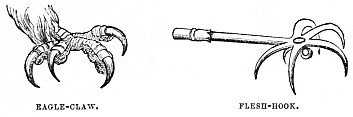

On the accompanying illustrations are shown a number of corresponding forms of the Anchor, together with a few others, which, although they may not necessarily be used in the water, are nevertheless constructed on the same principle—i.e. for the purpose of grappling.

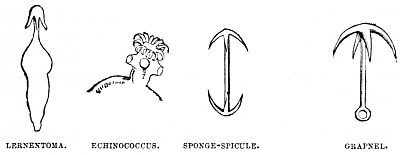

One of the most startling parallels may be seen on the right hand of the illustration, the figure having been drawn from an old Roman coin. On the other side of the same illustration may be seen an anchor so exactly similar in form, that the outline of the one would almost answer for that of the other. This object is a much-magnified representation of a spicule which is found on the skin of the Synapta, one of the so-called Sea-slugs, which are so extensively sold under the name of Bêche de Mer. It forms one of the curious group called the Holothuridæ.

Each of these anchors is affixed to a sort of open-worked shield, as shown above, and on the left hand; and it is a curious fact that in the various species of Synapta the anchor is rather different in form, and the shield very different in pattern. They are lovely objects, and I recommend any of my readers who possess a microscope to procure one. They need a power of at least 150 diameters to show their full beauties.

An ordinary Grapnel is here shown, and in the corresponding position on the opposite side is an almost exactly similar object, except that it is double, having the grapnel at both ends of the stem. This is a spicule of a species of sponge, and is one of the vast numbers of which the sponge principally consists.

Next to the sponge-spicule is a still more perfect example of a natural Grapnel. This is the head of an internal parasite called Echinococcus, which holds itself in its position by means of the circle of hooks with which the head is surrounded. These hooks are easily detached, and have a curious resemblance to the claw of the lion or tiger.

On the left-hand side is a representation of a parasitic crustacean animal called Lernentoma, which adheres to various fishes, and is mostly found upon the sprat, clinging to the gills by means of its grapnel-shaped head.

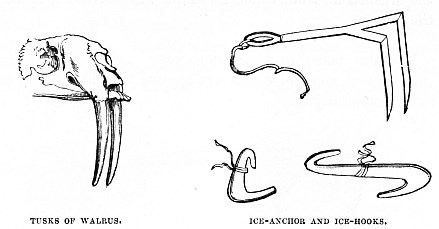

On the right hand of the accompanying illustration is an ice-anchor, copied from one of those which were taken out in the Arctic expedition of 1875. Opposite is the skull of the Walrus, the tusks of which are said to be used for exactly the same purpose. Below are ice-hooks, also used for the same expedition.

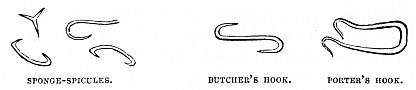

The next illustration exhibits a butcher’s hook and a common porter’s hook, by which he lifts sacks on his back; and opposite them are some sponge-spicules, the similarity of which in form is so remarkable that the former might have been copied from the latter.

Our next sketch shows a remarkable example of similitude in form. There are certain small anchors called Kedges, which are very useful for mooring a boat where no great power of resistance has to be overcome, and a large anchor would be cumbersome. One of these is called, from its shape, the “Mushroom Kedge,” and is very useful, as, however it may be dropped, some part of the edge is sure to take the ground. This Kedge is shown on the right hand of the illustration, and the Mushroom, from which its shape was borrowed, is seen on the left.

We now come to some more examples of the principle of the Grapnel, some of which are applied to nautical, and others to terrestrial objects.

The right-hand upper figure represents the “Flesh-hook,” used for taking boiled meat out of the caldron, so familiar to us by the reference to it in Exodus xxvii. 3, and the still better-known allusion to its office in 1 Samuel ii. 13, 14. In the former passage, even the material, brass, which was really what we now call bronze, is mentioned, and it is a curious fact that all the specimens in the British Museum, from one of which the drawing was taken, are made of bronze. I need hardly state that the hollow handle is meant to receive a wooden staff.

On comparing this figure with that of the Eagle’s foot on the opposite side, the reader cannot but be struck with the exact resemblance between the two. Indeed, there is very little doubt that the flesh-hook was intentionally copied from the foot of some bird of prey. Perhaps the Osprey would have furnished even a better example than the Eagle, the claws being sharper and more boldly curved, so as to hold their slippery prey the better.

On the left hand of the next illustration is a figure of the seed-vessel of the Grapple-plant of Southern Africa, drawn from a specimen in my collection. The seed-vessel is several inches in length, and the traveller who is caught by a single hook had better wait for assistance than try to release himself. The stems of the plant are so slender, and the armed seed-vessels so numerous, that in attempting to rescue one portion of the dress, another portion becomes entangled, and the traveller gets hopelessly captured. Besides the hooks of the seed-vessels, the branches themselves are armed with long thorns, set in pairs. The scientific name of this plant is Uncinaria procumbens, the former word signifying “a hook,” and the latter “trailing.” It is also known by the popular name of Hook-plant.

In the late Kafir wars the natives made great use of this and other plants with similar properties, their own naked, dark, and oiled bodies slipping through them easily and unseen, while the scarlet coats of the soldiers were quickly entangled, and made them an easy mark for the Kafir’s spear. In this way many more of our soldiers were killed by the spears than by the bullets of their enemies.

Opposite to the Grapple-plant is shown the common Drag, which is utilised for so many purposes. Generally it is employed for recovering objects that have sunk to the bottom of the water, and its use by the officers of the Humane Society is perfectly well known, the Drag being sometimes affixed to the end of a long pole, like the flesh-hook already described, and sometimes tied to a rope.

It can also be used as an anchor, after the manner of a kedge, and has been often employed in naval engagements for the purpose of drawing two ships together, and preventing the escape of the vessel which is being worsted. My relative, the late Admiral Sir J. Harvey, K.B., used drags in this manner, and secured two French ships, one on either side, namely, L’Achille and Le Vengeur. The first was sunk, and the second captured.

CHAPTER V.

SUBSIDIARY APPLIANCES.

Part III.—The Boat-hook and Punt-pole.—The Life-buoy and Pontoon-raft

The Boat-hook and its varied Uses.—The Earth-worm and the Serpula.—Microscopic Boat-hooks.—The Life-belt.—Life-boats and their Structure.—Uses of Cork.—Wine Corks made serviceable.—The Life-collar.—Portuguese Man-of-war.—Captain Boyton’s Life-dress.—The Life-raft.—Victualling a Yacht and Boat.—The Janthina and its Air-vessels.—Cask-pontoon—Pottery-raft and its Uses.

AS all rowing men know, an indispensable appliance to the boat is the Boat-hook, which can be used either as a pole, wherewith to push the boat along, or as a grapnel, by which it can be drawn towards the shore or a ship. As the latter portion has been discussed at the close of the preceding chapter, we may proceed to the former.

Every one knows how a boat may be propelled by a pole pressed against the bank or the bottom of the water, and that there are certain boats, called punts, which are propelled in no other way.

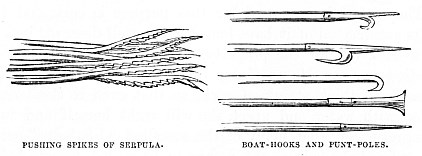

Now, the punt-poles and boat-hooks, of which some examples are given in the accompanying illustration, have long been anticipated in Nature, there being many creatures which have no other mode of progression; such, for example, as the common Earth-worm, which pushes itself along by certain bristles which project from the rings of which the body is composed, and which have the power of extension and contraction to a wonderful extent. As, however, I shall advert to these in another part of the work, I will content myself at present with a single example, namely, the beautiful marine worm known as the Serpula.

This worm lives in a shelly tube, which is lined with a delicate membrane, up and down which it passes with ease, ascending slowly, but generally descending with such wonderful rapidity that the eye cannot follow its movements. The latter movement will be explained in a subsequent part of the book, and we will at present only treat of the former.

If the creature be removed from the tube, and carefully examined, a number of projections will be seen, in each of which is a perforation. If the animal be pressed, a slight glass-like bristle passes through the perforation, and can easily be removed. If properly treated, and placed under a high power of the microscope, the tiny bristle resolves itself into the remarkable object which is shown on the left hand of the illustration.

It consists of a number of spear-like rods, each having a straight shaft, and a curved and pointed tip, deeply barbed on the inner portion of the curve. These curious bundles of spicules can be protruded or retracted at pleasure, and, as they are all directed backwards, it is evident that when they are pushed against the sides of the tube, either the points or the barbs must catch against the membrane which lines the tube, and so propel the animal upwards. When it wishes to descend, it uses another set of implements, and withdraws the first within their sheaths.

This is exactly analogous to the mode of progression employed by punters, who, after they have placed the pole against the bed of the stream, and run along the punt so as to push it as fast as possible, immediately withdraw the pole, and take it to the head of the punt, ready for another push. This, as the reader will see, is exactly the plan pursued by the Serpula in lengthening itself when it wishes to advance, and so to press its spicules against the sides of its tube, and in shortening itself and withdrawing the spicules ready for another push.

Another needful accessory of vessels now comes before us, namely, the capability of forming rafts or life-belts, which will float under any circumstances. Here, again, every human invention of which I know has been anticipated by Nature. Take, for example, the familiar instance of the cork life-belt and the cork edgings of the life-boat. Both are constructed on the same principle, i.e. the maintenance of cells which are filled by air instead of water, and are impervious to the latter.

The material most used for this purpose is cork, and life-belts constructed of it have long been in well-deserved use, the cork-bark having the property of holding much air and excluding water. Many of our life-boats are furnished with a broad and thick streak of cork, so that even if the boat be filled with water and upset, she will right herself and swim. I regret to say that many of the so-called “life-belts” which are offered for sale ought rather to be called “death-belts,” they having been found to be filled with hay and straw, with only a few shavings of cork just under the covering of the belt.

Indeed, so buoyant is this substance that a very efficient belt can be made by stringing together three or four rows of ordinary wine corks, and tying them round the neck like a collar. Under these circumstances it is simply impossible to sink, and though any one may collapse from exhaustion, drowning is almost out of the question. The now well-known cork mattress, which is used in many ships, is another example of the same principle.

Lately there has been invented a “life-collar,” which possesses similar advantages, but occupies less space when not wanted. It is nothing more than a tube of caoutchouc, which can be inflated at pleasure, and tied round the neck. The ordinary life-belt goes round the waist, and needs much more material without obtaining a better result, which is simply the keeping of the mouth and nostrils out of the water.

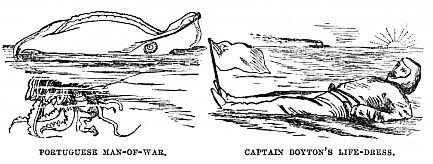

Perhaps the most buoyant of living beings is the Portuguese Man-of-war (Physalis pelagicus), which floats on the surface of the ocean like a bubble. It can at pleasure distend itself with air and float, or discharge the air and sink.

Now, there is a very remarkable swimming dress, which, though not entirely invented, was at least perfected by Captain Boyton, and which, as it enabled the wearer to cross from France to England under rather unfavourable circumstances, is clearly a most valuable invention.

Whether the inventor knew it or not I cannot say, but the Boyton life-dress is simply a modification of the Physalis, being capable of dilatation with air at will.

So much for the individual life-belt, and we will now pass to those which are intended to sustain more than one individual. It has almost invariably been found that when a ship has been wrecked on a rock, or stove in by the sea, that, although there may be plenty of boats, there is great difficulty in getting them into the water rightly.

Now, if parts of the ship itself could be made of materials which could not be sunk except by enormous pressure, and which might be released by a touch if the vessel were sinking, it is evident that many lives would be saved which have now been lost.

And if such movable parts of the vessel were supplied with water and provisions in air-tight cases, there is no doubt that the number of “missing” ships would be very greatly diminished. I remember an instance where a yacht was “hung up” on a mud-bank, whence there was no escape, for twenty-four hours, and there was one sandwich on board to be divided among the owner, two men, and a boy. Of course the boy had the sandwich, and the men sustained themselves as well as they could with tea, of which there was, fortunately, a canister on board. As it was, they were some thirty-six hours without food.

After such an experience the owner had special lockers made in the yacht and her boat, containing biscuit, potted meats, water, wine, spirits, tobacco, tea, an “etna” for heating the water, and matches. Of course these were on a smaller scale in the boat; but several thick rugs were also stowed away, in case of being separated from the yacht at night. It so happened that they were never needed; but the sense of security which they imparted was worth ten times the expense and trouble, which included a careful inspection of all the stores before each voyage.

In Nature there is just such a raft as is needed, capable of carrying a heavy freight, and which cannot be upset. And it is rather remarkable that it has been unconsciously imitated in various parts of the world.

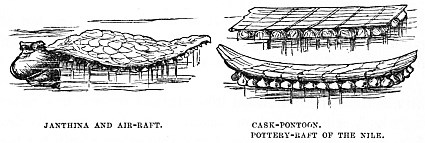

This is the singular apparatus attached to the Violet Snail (Janthina communis), which is common enough in the Atlantic, and derives its name of Violet-shell from its beautiful colour. The chief interest, however, centres in the apparatus which is popularly called the “raft,” and which sustains the shell and eggs. It is made of a great number of air-vessels, affixed closely to each other, and by the curious property of bearing its cargo slung beneath it instead of being laid upon it.

Beneath the raft are the eggs, or rather, the capsules which contain the eggs, and at one end is the beautiful violet shell itself. The floating power of the raft is really astonishing, and even in severe tempests, when it is broken away from the animal, the raft continues to float on the surface of the waves, bearing its cargo with it.

On the opposite side of the illustration are two examples of rafts constructed so exactly on the same principle as that of the Violet Snail, that they both might have been borrowed from it.

The upper is the kind of raft which has often been constructed by sailors when trying to escape from a sinking ship, or by soldiers when wishing to convey troops across a river, and having no regular “pontoons” at hand. It is made simply by lashing a number of empty casks to a flooring of beams and planks.

The amount of weight which such a structure will support is really astonishing, as long as the casks remain whole, and to upset it is almost impossible. Even cannon can be taken across wide expanses of water in perfect safety, and there is hardly anything more awkward of conveyance than a cannon, with its own enormous and concentrated weight, and all the needful paraphernalia of limber, ammunition (which may not be wetted, and of immense weight), horses, and men.

Yet even this heterogeneous mass of living and lifeless weight can be carried on the cask-raft, which is an exact imitation of the living raft of the Violet Snail.

Beneath the cask-pontoon is to be seen a sketch of a very curious vessel which is in use on the Nile, and I rather think on the Ganges also, though I am not quite sure. It is formed in the following manner:—

In both countries there are whole families who from generation to generation have lived in little villages up the river, and gained their living by making pottery, mostly of a simple though artistic form, the vessel having a rather long and slender neck, and a more or less globular body.

When a man has made a sufficient number of these vessels, he lashes them together with their mouths uppermost, and then fixes upon them a simple platform of reeds. The papyrus was once largely used for this purpose, but it seems to be gradually abandoned.

He thus forms a pontoon exactly similar in principle with the cask-pontoon which has just been described. Then, taking his place on his buoyant raft, he floats down the river until he comes to some populous town, takes his raft to pieces, sells the pots and reeds, and makes his way home again by land.

WAR AND HUNTING

CHAPTER I.

THE PITFALL, THE CLUB, THE SWORD, THE SPEAR AND DAGGER

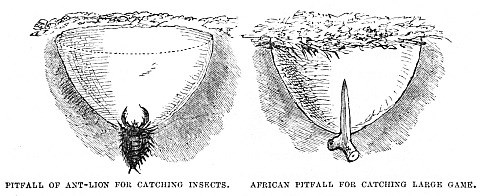

Analogy between War and Hunting.—The Pitfall as used for both Purposes.—African Pitfalls for large Game, and their Armature for preventing the Escape of Prey.—Its Use in this Country on a miniature scale.—Mr. Waterton’s Mouse-trap.—Pitfall of the Ant-lion, and its Armature for preventing the Escape of Prey.—The Club and its Origin.—Gradual Development of the Weapon.—The “Pine-apple” Club of Fiji.—The Game of Pallone and the “Bracciale.”—The Irish Shillelagh.—Clubs and Maces of Wood, Metal, or mixed.—The Morgenstern.—Ominous Jesting.—Natural Clubs.—The Durian, the Diodon, and the Horse-chestnut.—The Sword, or flattened and sharpened Club.—Natural and artificial Armature of the Edge.—The Sword-grass, Leech, and Saw-fish.—Spears and Swords armed with Bones and Stones.—The Spear and Dagger, and their Analogies.—Structure of the Spear.—The Bamboo as a Weapon of War or Hunting.—Singular Combat, and its Results.

THE two subjects which are here mentioned are practically one, the warfare being in the one case carried on against mankind, and in the other against the lower animals, the means employed being often the same in both cases.

The PitfallOne of the simplest examples of this double use is afforded by the Pitfall, which is employed in almost every part of the world, and, although mostly used for hunting, still keeps its place in warfare.

On the right hand of the accompanying illustration is shown a section of the Pitfall which is so commonly used in Africa for the capture of large game. It is, as may be seen, a conical hole, the bottom of which is armed with a pointed stake. Should a large animal fall into the pit, the shape of the sides forces it upon the stake, by which it is transfixed. Even elephants of the largest size often fall victims to this simple trap. It is only large enough to receive the fore-legs and chest, but that is quite sufficient to cause the death of the animal, the stake penetrating to the heart.

Many a hunter has fallen into these traps, and found great difficulty in escaping, while some have not escaped at all. Indeed, in many parts of Southern Africa, when part of one tribe is about to visit another, the pitfalls are always unmasked, lest the intended guests should fall into them.

Even without the spike, the elephant would scarcely be able to save itself, owing to its enormous weight, unless helped out by its comrades before the hunters came up. Indeed, many pitfalls are intentionally made for this purpose, and are of a different shape, i.e. about eight feet in length and four in breadth.

In those which are made for the capture of the giraffe, the pit is very deep, and the place of the stake is occupied by a transverse wall, which prevents the feet of the captive from touching the ground, and keeps it suspended until the hunters can come and kill it at leisure.

Even in Belgium and our own country the pitfall is in use. When the field-mice were devastating the districts about Liege some years ago, their ravages were effectually checked by pitfalls, in which they were caught by bushels, the pitfalls being simple holes some two feet deep, and made wider below than above.

The late Mr. Waterton contrived to rid his garden of field-mice by pitfalls constructed on the same principle, though more permanent. Finding that the little animals made great havoc among his peas just as they were starting out of the ground, he buried between the rows a number of earthen pickle-jars, sinking them to the level of the ground. He then rubbed the inside of the neck with bacon, and left them. The mice stooped down to lick off the bacon, fell into the jars, and, the neck being narrow and the sides slippery, they could not get out again.