полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

There is a curious variety of blue and white in which the outline of the design is filled up by a hatching of cross-lines as in an engraving. The prototype of this kind of decoration probably dates from Ming times, and it may possibly be derived from some kind of textile.

Enamel Colours over the Glaze.—We have already attempted to follow the stages by which the application of enamel colours over the glaze found its way into general use. We saw that before the introduction of fusible enamels melting at the gentle heat of the muffle-stove, somewhat similar effects were obtained by painting with certain colours upon the already fired body or paste—on a biscuit ground, in fact. The coloured slip used in this way, differing in no respect from a true glaze, was then subjected to a fire of medium intensity, that is to say, it was exposed to the demi grand feu of the kiln.

I think that the obscure problem of the nature of the coloured ware so minutely described by Chinese writers and ascribed by them to early Ming times, and the relation of this ware to the first forms of the famille verte can only find its solution by allowing a wider play to the use of painting on biscuit and subsequent refiring, and that there may probably have existed intermediate stages between the demi grand feu and the fully developed muffle-stove. It is indeed possible that the same pieces may have successively been exposed to both these fires.101

The curious bowl, of very archaic aspect, lately added to the Salting collection (see note, p. 89), illustrates well the difficulties in accepting as final a decision as to date based upon the nature of the enamel. This bowl bears the nien-hao of Ching-te (1505-21), and may well date from that time, but among the enamel colours over the glaze we find a cobalt blue (of a poor lavender tint indeed); we are told, however, that the use of cobalt as an enamel colour was unknown before the time of Kang-he.102

Of the many schemes and varieties of decoration that crop up in the course of the eighteenth century as a consequence of the increased palette at the command of the enameller and of the miscellaneous demand for foreign countries, we have already said something. Many important types must remain unmentioned, and some are indeed scarcely represented in our home collections. Of this I will give, in conclusion, a striking instance. In the whole of the great collection at Dresden, now so admirably arranged by Dr. Zimmermann, there is perhaps nothing more striking than the circular stand covered with a trophy of large vases, the decoration of which, though bold in general effect, is entirely built up by fine lines of iron-red helped out by a little gold. These vases, from their fine technique, I should assign to the end of the reign of Kang-he, or possibly to that of Yung-cheng (1722-35). It is a curious fact that by these parallel lines of iron-red an effect is produced at a distance very similar to that obtained by a wash of the rouge d’or. Possibly the aim was to imitate that colour. I have seen a similar effect produced by red hatching on some English ware of the eighteenth century. I do not think that this porcelain was made for the Persian market, as has been asserted, for in that case we should find specimens of it in the South Kensington collection.103 There is, I think, only one example of this ware in the British Museum, and in the Salting collection only a pair of insignificant cups and saucers. On the other hand, in the Dresden collection, whole classes even of eighteenth century wares are unrepresented. I mention these facts to accentuate the vast field covered by Chinese porcelain. It must be borne in mind that the Chinese manufactured for the whole civilised world, and that the taste and fashion in each country influenced, though often very indirectly, and in a way not always to be recognised at first sight, the forms and the decoration of the objects exported to it. This influence, making for variety and change, has been in constant conflict with, and has counteracted, the native conservative habit. It is an influence that has probably made itself felt from very early days, but it culminated in the eighteenth century. Indeed the rapid decline of Chinese porcelain that set in before the end of that century was in no small degree promoted by the unintelligent demand from Western countries at that time.

We shall later on have to look upon this question

from a reversed point of view, and we shall have to notice how the fictile wares of other countries were influenced, and finally in part replaced by the products of the kilns of King-te-chen. For in any general history of porcelain this influence of the East upon the West, together with the return current from West to East, is the central question. By bearing in mind these mutual influences a simplicity and unity are given to this history which we might look for in vain in that of any other art of equal importance.

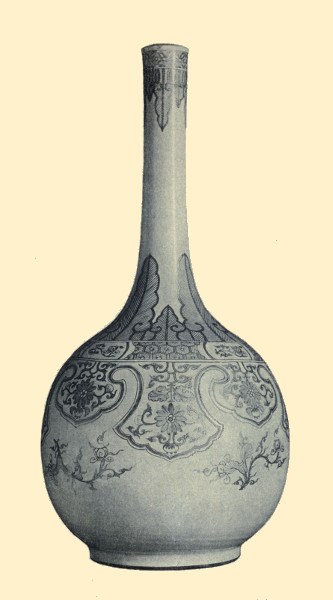

Plate XX.

Chinese Design in red and gold.

How the porcelain of King-te-chen found its way at first to the surrounding minor states—to Korea, to Indo-China, and to Japan—and was more or less successfully copied in these countries; how, on the other hand, in India and in Persia the foreign ware, though long in general use, was never imitated;104 and how, finally, after reaching the Christian West this porcelain influenced and in part replaced the homemade fayence, even before the secret of its composition was discovered—these, I think, are the prime factors in the history of porcelain.

It will, however, be convenient to say something of the porcelain made in the surrounding countries, especially in Japan, before taking up the subject of the Chinese commerce with Europe, for this reason among others: the products of the Japanese kilns became so inextricably mixed up with those of King-te-chen in the course of their journey to the West, that it would be impossible to treat of the one class apart from the other.

But before ending with the porcelain of China we must take a rapid glance at a large and complicated group—that decorated wholly or in part in European style.

Quite early in the century, perhaps before 1700, figures and groups in plain white ware, for the most part attired in the European costume of the day, were exported from China. Many of these grotesque figures may be seen in the great Dresden collection, and a few in the British Museum. Later on it became the fashion for the European merchants at Canton to supply the native enamellers of that city with engravings, to be copied by them in colours on the white ware sent down from King-te-chen. In other cases the captain of a Dutch or English vessel lying in the Canton roads would employ a native artist to decorate a plate or dish with a picture of his good ship.

But the most frequent task given to these Canton enamellers was the reproduction of elaborate coats of arms upon the centre of a plate or dish, or sometimes upon a whole dinner-service. There is in the British Museum a remarkable collection of this armorial china, brought together for the most part by the late Sir A. W. Franks.105 Orders came not from England alone, but from Holland, Sweden, Germany, and even Russia. Services were thus decorated for Frederick the Great and other royal heads. The practice seems to have been kept up during the whole of the eighteenth century, but we do not know the precise date at which it was introduced. In a few cases—the large Talbot plate in the British Museum is an instance (Pl. xxi.)—the arms were painted in blue under the glaze, and such decoration was probably executed at King-te-chen. The small plate with the Okeover arms in the same collection was, according to the family tradition, ordered as early as the year 1700, but the decoration in my opinion would undoubtedly point to a later date106 (Pl. xii. 2).

PLATE XXI. CHINESE, BLUE AND WHITE WARE

It is hardly necessary at the present day to mention that this armorial china has nothing to do with Lowestoft. A fictitious interest was, however, long given to this ware by its strange attribution to that town.

Much Chinese porcelain, either plain white or sparely decorated under the glaze with blue, was imported during the eighteenth century, to be daubed over, often in the worst taste, with a profusion of gaudy colours, in Holland, in Germany, and in England. At Venice, too, the plain Oriental ware was at one time elaborately painted with a black enamel.

More interest attaches to the porcelain enamelled at Canton for the Indian market. The Chinese seem in some way to have associated the yang-tsai or ‘foreign colours’ with the enamels made in the south of India, especially at Calicut, and it is possible that Indian patterns and schemes of colour may have influenced some of the developments of the famille rose. The Canton enamellers must at the same time have been working on the richly decorated ware for the Siamese market, but it is on their enamel paintings on copper that the Indo-Siamese influence is chiefly seen (see next chapter).

Nor were these exotic schemes of decoration confined to the Canton enamellers. At more than one time there was something like a rage for copying foreign designs—Japanese, among others—at King-te-chen, and that not for trade purposes alone, for as we have mentioned already, both Kang-he and Kien-lung seem to have taken a passing interest in the strange productions of the outer barbarian.

Of the many kinds of ceramic wares made in different parts of China which from the opacity of the paste we cannot class as porcelain, we can only mention two, both of which would probably come under the head of our kaolinic stoneware:—1. The Yi-hsing yao, made at a place of that name not far from Shanghai, which includes the red unglazed ware, esteemed by the Chinese for the brewing of tea. This is the so-called Boccaro successfully copied by Böttger. Sometimes we find this stoneware painted with enamel colours thickly laid on, and the design is often accentuated by ridges or cloisons. 2. The Kuang yao, of which there are two classes. The ware made near Amoy is a yellowish to brownish stoneware, thickly glazed and rudely decorated. This coarse pottery is much in favour with the Chinese colonists in America and elsewhere. Again in the south of the province of Kuang-tung, at Yang-chiang-hsien, a reddish stoneware has long been made. It is covered with a thick glaze, often mottled, more or less blue, and sometimes resembling the flambé glazes of King-te-chen. Indeed this Kuang yao at one time was copied at the latter place.107 It is often stated that true porcelain was made in Kuang-tung, but the evidence on the whole is against this. We will quote, however, what the Abbé Raynal says (Histoire du Commerce des Européens dans les Deux Indes, 1770). He states that competition with King-te-chen had been abandoned ‘excepté au voisinage de Canton, où on fabrique la porcelaine connue sous le nom de porcelaine des Indes. La pâte en est longue et facile; mais en général les couleurs sont très inférieures. Toutes les couleurs, excepté le bleu, y relèvent en bosse et sont communément mal appliquées. La plupart des tasses, des assiettes et des autres vases que portent nos négocians, sortent de cette manufacture, moins estimée à la Chine que ne le sont dans nos contrées celles de fayence.‘108 Compare with this what we have said about the rough porcelain exported to India in the seventeenth century (p. 85).

Since the extinction of the Ting kilns an opaque white stoneware has been largely manufactured in the north, and near Pekin a commoner earthenware is largely made (Bushell, pp. 631-638).

The bricks with which the Porcelain Tower of Nankin was constructed were for the most part composed of a kaolinic stoneware.

Finally, we should point out that nearly all these various kinds of stoneware are represented in the British Museum collection.

CHAPTER XI

THE PORCELAIN OF KOREA AND OF THE INDO-CHINESE PENINSULA

KoreaTHE self-contained culture of the Middle Kingdom spread at an early time to the less advanced and more or less tributary countries that surrounded it: on the south to the confused complex of states that are conveniently grouped together as Indo-China; on the north to Korea; and on the east, or more accurately on the north-east, to Japan. To these islands, however, the Chinese civilisation for the most part spread by way of Korea, and as this was in a measure the route taken in the case of the potter’s art, it may be well to deal first with the great northern peninsula.

The Chinese claim to have conquered and even incorporated Korea as long ago as the Tang dynasty (618-907 A.D.), and even before that time the country had been overrun by the Japanese. The latter people have at all times presented themselves to the Koreans as ruthless conquerors and pirates, and indeed they succeeded during their last great expedition at the end of the sixteenth century in sweeping the country so bare that to this day its poverty and the low state of its artistic culture is generally attributed to this gigantic razzia from which the country never recovered. And yet Korea has always taken a place in Japanese estimation second only to China as a source of their artistic and practical knowledge, if not of their literature and philosophy; and this is especially the case with regard to the potter’s craft—the technical part of it above all. Time and again do we hear of famous Korean potters, or even of whole families and tribes, being brought over and set to work by the local Japanese ruler either with the materials they brought with them, or with the clays and glazes that their experience enabled them to discover in their new homes.

We need not, therefore, be surprised to find that after the wonders of Japan had been laid open to the admiration of the West, the greatest hopes were entertained of finding artistic treasures at least as valuable in the great peninsula to the west which still remained a forbidden land. Failing direct evidence of this wealth, it became the habit to attribute to Korea any Oriental ware, old or new, of which the origin was unknown. This tendency was taken advantage of by more than one enterprising dealer, and when at a later time the country was in a measure thrown open, cases of gorgeously decorated Japanese ware, brand-new from Yokohama or Nagasaki, were sent round by way of Chemulpo, the port of the Korean capital, so that their Korean origin could be guaranteed. Long before this, the home of an important group of Japanese porcelain, that now generally known as ‘Kakiyemon,’ had been found by Jacquemart in Korea. Now that of late years these various fallacies and supercheries have been exposed, and that the extreme poverty of the land in artistic work of any kind has been demonstrated, we may perhaps see a tendency to an undue depreciation of the artistic capabilities of the country in former days. We must at any rate remember that the Japanese experts, who are in the best position to know, have always maintained that the Koreans in the sixteenth century were possessed of the secret of enamelling in colour upon porcelain, or, at all events, that they were acquainted with the coloured glazes of the demi grand feu, and that so good an authority as Captain Brinkley has accepted, as of Korean origin, specimens of enamelled ware still existing in Japanese collections.

Meantime we must be contented with the scanty examples of pottery, stoneware, and porcelain that have been actually brought home from Korea, and among these pieces we must discriminate between the wares of native manufacture and the porcelain that had been imported from China, either overland by way of Niu-chuang or across the Gulf of Petchili from the ports of Shantung. Of late years many specimens have been collected, chiefly at Seoul, the capital, especially by members of the various foreign legations, and some of these have found their way into European museums.109

Apart from some small pieces of modern blue and white and enamelled wares, undoubtedly of true porcelain, but very rough in execution and poor in colour, which are said to be of local manufacture, we find:—

1. A plain white ware often showing signs of age, but apparently in no way differing from the ivory-white ware of Fukien. Japanese experts, however, claim to distinguish pieces of Korean origin. Such specimens are much valued in Japan, and some are said to have been brought back after the great expedition at the end of the sixteenth century. We find also specimens of a heavy white ware, with decoration in a high relief, which is undoubtedly of native origin. At Sèvres is a large white vase, with dragons in relief, brought from Seoul.

2. Celadon porcelain, of many types. Of this ware there are many specimens in our museums. At Sèvres we find two bowls of a fine rich tint of olive green, presented by the King of Korea to the late President Carnot ‘as the most valuable of the ancient productions of his poor country.’ In the same collection may be seen a case full of important specimens brought back in 1893 by M. de Plancy, the French diplomatic agent at Seoul. Among them are some large rude celadon vases, one with some attempts at blue decoration under the glaze. In the British Museum are several celadon bowls, some with moulded floral patterns in relief. Among some bowls of a greyish celadon from Korea, in the Ethnographical Museum at Dresden, I noticed some with an unglazed ring on the upper surface, pointing to a primitive method of support in the furnace, perhaps similar to that formerly employed in Siam. Dr. Bushell quotes from a Chinese work on Korea, written in the first half of the twelfth century, an account of the elaborately moulded wine-cups and vessels of all kinds made in that country. This ware is described as of a kingfisher green, but it may probably be regarded as a full-coloured variety of celadon. This interpretation is confirmed by a later Chinese work (published 1387), which distinctly says—I quote from Dr. Bushell’s translation—‘The ceramic objects produced in the ancient Korean kilns were of a greyish green colour resembling the celadon ware of Lung-chuan. There was one kind overlaid with white sprays of flowers, but this was not valued so very highly’ (Oriental Ceramic Art, p. 681).

3. An important class of Korean ware is formed by the coarsely crackled pieces of brownish or yellow colour, which in China would probably be classed as Ko yao. These are often roughly decorated with daubs of blue under the glaze, resembling in this some of the older pieces brought from Borneo.

4. A greyish ware, inlaid with designs of white slip, on the principle of our ‘encaustic tiles’ of the Middle Ages. This is perhaps the only original type that we can connect with Korea, and it would seem that this is the ware alluded to at the end of the quotation we have just given from an old Chinese book. This inlaid ware appears to have been greatly admired by the Japanese, for it was closely imitated in more than one district. The well-known Yatsushiro pottery, first made in the province of Higo in the seventeenth century, is distinctly a copy of this Korean model. Among the specimens at Sèvres brought home by M. de Plancy, there is a tall vase of this type cut down in the neck decorated with flying cranes in white slip. This ware, however, is not a true porcelain; at the best it is a kind of kaolinic stoneware, and the same may be said of most of the old heavy pieces brought back from Korea.

There is not much in the way of decorative design to be found on any of the varieties of Korean porcelain or stoneware that we have now described, and we may look in vain among the few ornamental motifs to be found on these wares for any marked divergency from Chinese types.

Siam and the Indo-Chinese PeninsulaUnder the somewhat vague heading of Indo-China we will collect a few notes upon the specimens of porcelain that have been found in the various states into which the great peninsula that stretches south between the China Sea and the Bay of Bengal is divided.

In looking through the artistic productions of all these countries, we find one marked characteristic; and that is the way in which Chinese forms and Chinese decorative motifs have pushed their way in and in part replaced the old Buddhist and Brahmanistic styles.

As matters now stand, the most important for us of these states is Siam, for here we are at once brought face to face with one of the places of manufacture of the famous heavy celadon ware which in the Middle Ages was carried by Arab and Chinese traders over all the seas of the then known world. We shall have in a later chapter to come back to the question of this trade, and then we shall be able to show that the discussion as to the origin of this martabani ware has been the means, as is indeed often the case in such disputes, of throwing much light on the early history of Chinese porcelain.

For the present we are only concerned with an important discovery quite recently made not far from the frontier of Siam and Pegu. Many specimens of celadon, some of the older type, have come in recent years from various parts of Indo-China. In the museum at Sèvres are some pieces of rough greyish ware, with a thick, irregularly crackled glaze, brought back in 1893 by the Mission Fournereux from Siam and Cambodia; among these fragments of old celadon we find a pair of contorted bowls, fused together in the kiln, in fact undoubted ‘wasters,’ such as could only be found in the neighbourhood of the furnaces where they were fired. At the instigation of Mr. C. H. Read of the British Museum, Mr. Lyle has lately explored the remains of old potteries now hidden in deep jungle, at a place called Sawankalok, not far from the western frontier of Siam. These old kilns are situated some two hundred miles to the north of Bangkok, and about the same distance from the port of Molmein (Malmen). To show the importance of this discovery, we need only point out that near to the latter town lies the old port of Martaban, which played so important a part in the mediæval trade of the Arabs, and from which, doubtless, the name of Martabani, by which celadon ware has always been known in the Mohammedan East, is derived. Among the many fragments brought back by Mr. Lyle are some which from their distinct translucency, and from the whiteness and the conchoidal fracture of the paste, may be unhesitatingly classed as true porcelain. The colour of the glaze varies from a prevailing greyish green to a fine turquoise tint in a few specimens. That the ware was made on the spot is proved by the presence of many defective pieces—‘wasters’ that had been thrown away—as well as by the numerous conical props (for the support of the ware in the kiln) found mixed with the fragments. On these tall, nozzle-shaped props the plates and bowls were supported in an inverted position. It is by this unusual method of support that we may account for the fact that the glaze covers the whole of the lower surface—so exceptional an occurrence in the case of porcelain—and at the same time for the absence of the glaze from a ring-like portion of the upper surface. We may note that a similar distribution of the glaze is found occasionally on large plates of the old heavy ware brought from other countries; of this there are notable examples in the museum at Gotha (see page 72). The ground in these Siamese specimens has assumed where exposed, but there only, the deep red so admired by the Chinese in the old Lung-chuan ware. The paste, in many of the examples, has been moulded in low relief in the characteristic lotus-leaf pattern, while on a few pieces there is a rough decoration in greenish black under the glaze. All remembrance of these old kilns has completely passed away, and at the present day the local market is supplied with a rough stoneware brought overland from Yunnan.110

The porcelain now found in Siam, of which many specimens have been lately brought to Europe, is of a very different character. This is the highly decorated enamelled ware which may be classed with the famille rose from the prevalence of the rouge d’or among the enamels. This ware, none of which can be earlier than the middle of the eighteenth century, is certainly made in China, but the presence in the decoration of certain peculiar Buddhist types makes it rather difficult to believe that the enamelling was in all cases executed in Canton. It is true that in the colours, and in the general style of the decoration, we are often reminded of the well-known Cantonese enamels on copper. The white surface of the ground is, for the most part, entirely hidden by a floral decoration; but amid this, on medallions surrounded by tongues of flame, we find centaur-like monsters with human heads, above which rise almond-shaped nimbi. From the top of the cover of the hemispherical bowls—the commonest form—rises a knob in the shape of the Buddhist jewel. The enamel of this ware appears to scale off readily, as if from imperfect firing. The prevailing colours are a deep red for the ground, and a bright green relieved with white and yellow for the design (Pl. xxii.). While the finer specimens, as we have already said, remind us of the Canton enamels, others suggest rather, in the scheme of colour and decoration, the painted and lacquered bowls of India and Ceylon. In the Indian Museum at South Kensington may be seen an exceptionally fine collection of this Sinico-Siamese porcelain, lent by Signor Cardu, and a good opportunity is here provided for comparing its decoration with that on the rough earthenware from Ceylon and various parts of India which is exhibited in adjacent cases.