полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

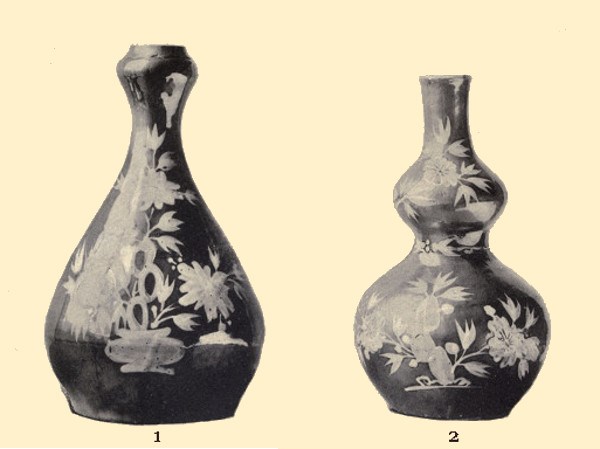

The brown glazes form a very distinct class. The well-known colour has many names: in French fond laque; in Chinese tzu-kin, or ‘burnished gold.’ It is also known as ‘dead leaf,’ but the average tint is perhaps best described as café au lait. The Père D’Entrecolles, in mentioning the tzu-kin, the colour of which he says is given by a ‘common yellow earth,’ states that it was a recent invention in his time. He is perhaps referring to some special tint, for the colour was well known in Ming days. We have already spoken of the possible relation of this colour to the copper lustre of the fourteenth century Persian fayence. At a later time in the seventeenth century it was a favourite colour with the Persians, especially when decorated with delicate designs of flowers and ferns in a thin white slip (Pl. xvi.). It was largely exported at that time from China and cleverly imitated in the fayence and frit-pastes of Persia. Both the original Chinese ware and the Persian imitation are well represented at South Kensington by specimens brought from the latter country. This brown glaze is seldom found alone. It is a colour that stands well the full heat of the furnace, and it may be combined with a blue and white decoration or with bands of celadon. It forms the ground-colour of the so-called Batavian ware, and at one time a brown ring was by our ancestors held to be essential on the rim of a fine plate or bowl of blue and white porcelain.

PLATE XVI. CHINESE, WHITE SLIP ON BROWN GROUND

Turquoise and Purple Glazes.—As for the twin colours of the demi grand feu (the yellow in this group is quite subordinate), the so-called turquoise (including the peacock green and kingfisher blue of the Chinese) and the aubergine purple, the latter is seldom found alone. Both colours are distinguished by a very fine-grained crackle. Of the blue, when used as a single-glaze colour, we have spoken when describing the glazes of the demi grand feu.

Yellow Monochrome Glazes.—There are many shades of yellow found on Chinese porcelain: the imperial yellow of full yolk-of-egg tint, the lemon yellow, the greenish ‘eel-skin,’ and the ‘boiled chestnut.’ Only the first, the imperial yellow, is of importance as a monochrome glaze. This is the colour first used in the time of the Ming emperor Hung-chi (1487-1505), and his name is sometimes found on bowls and plates ranging in colour from a bright mustard to a boiled chestnut tint. There are some good specimens in the British Museum, and a curious piece, with a Persian inscription, at South Kensington, has already been mentioned when speaking of the reign of Hung-chi.

Cobalt Blue Monochrome Glazes.—We may distinguish three varieties of blue derived from cobalt, but the full sapphire of the blue and white ware is not found as a monochrome glaze:—

1. The Clair de lune. The term yueh-pai, or moon-white, was applied to more than one class of Sung porcelain, but above all to the Ju yao. In later times, when these primitive wares were copied, the colour was given by a minute quantity of cobalt, but it is very doubtful whether that pigment was known in early Sung days. The clair de lune glazes of Nien were considered second in merit only to the copper reds of that great viceroy. The uncrackled glazes of this class are often classed as celadon.

2. The Mazarin blue, known also as bleu fouetté or powder-blue.89 This glaze is blown on to the surface of the raw paste, in the manner described on page 30. It sometimes covers the whole surface, and is then generally decorated with floral designs in gold, but more often it forms the ground for vases and plates with large white reserves on which designs in enamel colours are painted.

3. The Gros Bleu, in the form of large plates and vases, was a great favourite with the Arabs and other Mohammedan races. This ware, too, was often covered with a decoration of gold. There is a magnificent plate of this class in the British Museum, and at South Kensington, in the India Museum, a tall, dark-blue vase which we have already mentioned. From Persia come many specimens of this deep blue ware, of a greyish or even slaty tint, decorated, like the fond laque, with flowers in a white slip.

Black Glazes.—Very near to this last class of blue glazes we may place the ‘metallic black,’ the wu-chin of the Chinese. According to the Père D’Entrecolles, this mirror-black is prepared by mixing with a glaze containing much lime and some of the same ochry earth that gives the colour to the brown glazes, a sufficient quantity of cobalt of poor quality. In this case no second glaze is required, and the vessel is fired in the demi grand feu, i.e. in the front of the furnace. Other blacks are painted on and covered with a second glaze. The large spherical vases with tall tubular necks show little trace generally of the gold with which the black glaze was originally decorated.

Green Glazes.—The peculiar tint of green, in varied intensity, that distinguishes the famille verte is seldom found as a single glaze; and of the green Lang yao, made by Lang Ting-tso in the early part of the reign of Kang-he, it is doubtful whether we have any representatives in our European collections. This glaze is said to be somewhat in the style of his more famous sang de bœuf.

The brilliant cucumber or apple-green of Ming times is shown in a pair of exquisite little bowls in the British Museum. Over the green glaze there is a scroll pattern of gold, and on the inside a blue decoration under the glaze. Almost identical with these is the bowl set in a silver-gilt mounting of English make dating from about the year 1540, now preserved in the Gold Room (Pl. v.). Of a similar but somewhat deeper tint of green are the rare crackle vases, generally of small size, of which there are specimens in the British Museum and in the Salting collection.90

Olive and Bronze Glazes.—The monochrome glazes of various shades of olive and bronze are for the most part produced by a soufflé process, in which on a base of one colour a second colour is sprinkled. Thus to form the ‘tea-dust’ a green glaze is blown over a reddish ground derived from iron. The wonderful bronze glazes, of which there are good specimens in the British Museum and in the Salting collection, are produced in a similar way. But some of these (and the same may be said of the ‘iron rusts‘) partake rather of the nature of the more elaborated glazes of the flambé class.

Red and Flambé Glazes (Pl. xvii.).—We have left the red glazes to the last, both from the complicated nature of the class and because one variety, the sang de bœuf, forms a transition to the ‘splashed’ or flambé division. A red glaze or enamel, we have seen, can be produced from three metals,—from gold, from copper, and from iron. With the Rose d’or, which may be classed as a monochrome enamel, when used to cover the backs of plates and bowls, we are not concerned here—it is not properly a glaze in our sense of the word. The red derived from the sesqui-oxide of iron was only successfully applied as a monochrome when, at a late period, the difficulties attending its use were overcome by combining the pigment with an alkaline flux. This is the Mo-hung or ‘painted red’ of the muffle-stove, which was painted over the already glazed ware, and therefore not properly itself a glaze. In fine specimens it approaches to a vermilion colour; it is the jujube red of the Chinese. It is with this colour, laid upon the elaborately modelled paste, that the carved cinnabar lacquer is so wonderfully imitated.91

But it is the red derived from copper that presents the most points of interest. Indeed we now enter upon a series of glazes, beginning with the pure deep red of the sang de bœuf, and then passing over the line to the long series of variegated or ‘transmutation‘92 glazes that have more than any others fascinated the modern amateurs of ceramic problems. We have already seen how these magic effects are produced by carefully modulating the passage of the oxidising currents through an otherwise smoky and reducing atmosphere in the furnace ((p. page 42).

PLATE XVII. CHINESE

The typical sang de bœuf, or the ‘red of the sacrifice,’ as the Chinese call it, was that made under the régime of Lang Ting-tso a forerunner of the three great directors of the imperial manufactory at King-te-chen, and in later times it was always the aim of the potter to imitate his work—the Lang yao—even in trifling details. According to the Père D’Entrecolles, to obtain this red the Chinese made use of a finely granulated copper which they obtained from the silver refiners, and which therefore probably contained silver. Some other very remarkable substances, he tells us, entered into the composition, but of these it is the less necessary to speak, as he confesses that great secrecy was maintained on the subject.

In looking carefully into a glaze of this kind, the deep colouring-matter is seen suspended in a more or less greenish or yellowish transparent matrix, in the form of streaks and clots of a nearly opaque material.93 The hue, in general effect, varies from a deep blood-red to various shades of orange and brown, but intimately mixed with the red, certain bluish streaks are sometimes to be seen in one part or another of the surface. The colours should stop evenly at the rim and at the base, which parts, if this is achieved, are covered with a transparent glaze of pale greenish or yellowish tint.

We have already seen that much depends upon the period of the firing at which the glaze becomes liquid or soft, and upon the exact degree of fluidity attained by it. Should the oxidising currents be allowed further play at the critical period of the firing, the blue and greenish stains and splashes will become more predominant, and we may either pass over to the flambé or ‘transmutation’ glazes, or finally the glaze may become almost white and transparent.

But we must hark back to the wares of the Sung period, to the Chün yao, to find the origin of these variegated glazes. These early Sung glazes were copied in the time of Yung-cheng, and if we are to believe the contemporary list, already quoted, of the objects copied, they were of a very complicated nature. In this class of flambé ware we must include also a large part of the so-called Yuan tsu (see page 77), a heavy kaolinic stoneware, certainly not all dating from the Yuan or Mongol period—a ware, indeed, still common in the north of China. This ware is roughly covered with a glaze of predominant lavender tint, speckled with red, and thus approaches to the ‘robin’s egg’ glaze of the American collector, though this latter is found on a finer porcelain of later times.

Another name which has been used to include many of these variegated glazes is Yao-pien or ‘furnace-transmutation.’ This last word very well expresses the process by which the colour is developed, but it must be remembered that this is not exactly the meaning that the word yao-pien conveys to the Chinese mind.94 With this term the happy accidents of the furnace were linked by the Père D’Entrecolles: he tells us that it was proposed to make a sacrificial red, but that the vase came from the furnace like a kind of agate. Dr. Bushell thinks that most of the fine pieces of this ware date from the time of Yung-cheng and Kien-lung (1722-1795), and he is of opinion that they were prepared by a soufflé process rather than by any ‘academic transformation’ of a copper-red glaze. ‘The piece,’ he says, ‘coated with a greyish crackle glaze or with a ferruginous enamel of yellowish-brown tone, has the transmutation glaze applied at the same time as a kind of overcoat. It is put on with the brush in various ways, in thick dashes not completely covering the surface of the piece, or flecked as with the point of the brush in a rain of drops. The piece is finally fired in a reducing atmosphere, and the air, let in at the critical moment when the materials are fully fused, imparts atoms of oxygen to the copper and speckles the red base with points of green and turquoise blue’ (Oriental Ceramic Art, pp. 516-17). Some practical experiments lately made in France would tend to show that the critical moment should be placed a little earlier, before the glaze is completely fused, for after that point is reached the surrounding atmosphere has little influence upon the metallic oxides in the glaze. It is to this capricious action of the furnace gases that are due those wonderful effects that may be observed in looking into these glazes, curdled masses of strange shapes and varying colour suspended in a more or less transparent medium, and assuming at times those textures resembling animal tissues which are graphically described by the Chinese as pig’s liver or mule’s lungs. It must be understood that into many of the more modern and apprêtés specimens of flambé ware the sources of the violent contrasts of colour are found not only in the oxides of copper and iron, but in those of cobalt and manganese also.

But in contrast to ‘the stern delights’ of these flamboyant wares there is another kind of glaze, chemically closely allied, for it is also of transmutation copper origin, of which the associations are of another kind. This is the peach-bloom, the ‘apple-red and green,’ or again the ‘kidney-bean’ glaze of the Chinese. Although claiming an origin from Ming times, this glaze is always associated with the great viceroy Tsang Ying-hsuan. The little vases and water-vessels of a pale pinkish red, more or less mottled and varying in intensity, are highly prized by Chinese collectors.

Decoration with Slip.—There is a class of ware which might perhaps claim a separate division for itself—I mean that decorated with an engobe or slip. We have already mentioned the most important cases where this engobe is applied to the surface of single-glazed wares: these are, in the first place, the fond laque (Pl. xvi.), and in a less degree certain blue and even white wares. The slip, of a cream-like consistency, is as a rule painted on with a brush over the glaze, generally, I think, after a preliminary firing.95 This engobe may then itself be decorated with colours, as we have seen in the case of the Ko yao, and the whole surface probably then covered with a second glaze.96 Sometimes when the ground itself is nearly white we get an effect like the bianco sopra bianco of Italian majolica. This carefully prepared and finely ground engobe contains, in some cases at least, the same materials as those employed in the preparation of the Sha-tai or ‘sand-bodied’ porcelain.

Pierced or Open-work Decoration (Pl. xviii. 1).—We may here find place for another kind of decoration, one much admired in Europe in the eighteenth century.

PLATE XVIII. 1—CHINESE, PIERCED WARE, BLUE AND WHITE

2—CHINESE, BLUE AND WHITE WARE

This is obtained by piercing the paste so as to form an open-work design, generally some simple diapered or key pattern, but sometimes flowers or figures of cranes. The little apertures or windows thus formed may be filled in by the glaze (if this is sufficiently viscous to stretch across them) in the simple process of dipping. In this case the glaze takes in part the place of the paste, and indeed in the closely allied ‘Gombroon’ ware of Persia it is the thick, viscous glaze rather than the friable sandy paste that holds the vessel together. It is the plain white ware to which this decoration is generally applied in China. There is one class where this pierced work is associated with groups of little figures, in biscuit, in high or full relief—as is well illustrated by a series of small cups in the Salting collection, some of which bear traces of gilding and colours.

The term ‘rice-grain’ was originally applied to the open-work diapers filled in with glaze. As a whole this kind of work may be referred to the later part of the reign of Kien-lung, and especially to that of his successor, Kia-king (1795-1820), so that it is not unlikely that the Persian frit-ware, some of which is of earlier date, may have served as a model.

Blue and White Ware.—This is, on the whole, the most important as well as the best defined class of Chinese porcelain. The Chinese name, Ching hua pai ti (literally ‘blue flowers white ground‘), defines its nature well enough.

We have no information as to the origin and development of blue and white porcelain in China, nor indeed do I know of any collection where an attempt has been made to classify the vast material. We must here content ourselves with a few notes which at best may indicate the ground on which such a classification should be made. We have seen (p. page 75) that there is at least some presumptive evidence that the Chinese may have derived their knowledge of the use of cobalt (as a material to decorate the ground of their porcelain) from Western Asia, at a time when both China and Persia were governed by one family of Mongol khans. For we know now that in Syria or in Persia, in the twelfth or early in the thirteenth century, a rough but artistic ware was painted with a hasty decoration of cobalt blue and covered with a thick alkaline glaze; while in China, at that time, we have no evidence for the existence of any porcelain other than monochrome.

It is possible that the earliest Chinese type of the under-glaze blue may be found in certain thick brownish crackle ware, decorated under the glaze, in blue, with a few strokes of the brush. Plates and dishes of this kind have been found in Borneo, associated with early types of celadon.97 A similar ware, not necessarily of great antiquity, is often found in common use in the north of China and, I think, in Korea, and with it we may perhaps associate the greyish-yellow Ko yao decorated with patches of blue and white slip.

It is very likely that there would be a strong opposition on the part of the Chinese literati to such a novel and exotic mode of decoration, but that such opposition would be less felt in the case of ware made for exportation, or it may be for use among the less conservative Mongols. We have an instance of a similar feeling in the protest that we know was made some two or three hundred years later against the application of coloured enamels to the surface of porcelain.

Of the thousands of specimens of blue and white porcelain in our collections there is probably no single piece for which we can claim a date earlier than the fifteenth century. We can, however, distinguish two types among the examples, which for the reasons given on page 83 we may safely assign to the Ming period. The first is distinguished by a pure but pale blue, and the design (generally somewhat sparingly applied) is carefully drawn with a fine brush. This, it would seem, was the ware imitated by the Japanese at the princely kilns of Mikawaji. The other type is distinguished by the depth and brilliancy of its colour, the true sapphire tint, differing from the later blue of the eighteenth century, in which there is always a purplish tendency. There are some good specimens of this type in the British Museum, but we will take as our standard a jar at South Kensington about twelve inches in height (Pl. xix.). The remarkable thickness of the paste in this vase shown in the neck, which has at some time been cut down, the marks of the junction of the moulded pieces of which it was built up, the slight patina developed in the surface of the glaze, are all signs that point to an early origin. But what is above all noticeable is the jewel-like brilliancy of the blue pigment with which the decoration—a design of kilin sporting under pine-trees—is painted.

PLATE XIX. CHINESE BLUE AND WHITE WARE

When we come to the reign of Wan-li (1572-1619), to which time we may assign the beginning of the direct exportation to Europe of Chinese porcelain, a period of decline has already set in. The rare pieces of blue and white so prized in Elizabethan and early Stuart days are in no way remarkable either in their execution or in their decoration.

We come now to an important class of blue and white ware which looms out large in many collections. I mean the big plates and jars with roughly executed designs often showing a Persian influence. The blue is never pure—indeed it is often little better than a slaty grey, and sometimes almost black. Most of what the dealers now know as ‘Ming porcelain’ may be included in this class. To understand the source of this porcelain we must refer the reader to what we shall have to say in Chapter xiii. about the trade of China with Persia in the time of Shah Abbas and with the north of India, during the reigns of the great Mogul rulers of the seventeenth century. The increasing demand from these countries coincided with a period of decline in China, for the period between the death of Wan-li in 1620 and the revival of the manufacture at King-te-chen towards the end of that century, is almost a blank in the history of Chinese porcelain. But the export trade that had sprung up at the end of the sixteenth century was actively carried on in spite of the political troubles, and at no other time was the nature of the ware produced so largely influenced by the foreign demand. But this demand was at first chiefly for the Mohammedan East, and what reached Europe was mostly the result of re-exportation from India and from the Persian Gulf.98 This picturesque and decorative ware is well represented at South Kensington by specimens obtained in Persia, and many fine pieces have lately been brought from India. Of this class of blue and white ware we have already spoken in a former chapter (see page 84).

In Egypt, again, blue and white porcelain was greatly appreciated both for decorative purposes and for common use. Large plates and dishes painted with a scale-like pattern, formed of petals of flowers, are still to be found in the old Arab houses of Cairo.

Already by the beginning of the seventeenth century plates and bowls of the Sinico-Persian type must have reached Holland in large quantities, and we find them frequently introduced into their pictures by the still-life painters of the time. I will only give two examples: (1) A large still-life at Dresden by Frans Snyders (1579-1657), where as many as eight plates and bowls, mostly roughly decorated with a greyish cobalt sous couverte, are introduced; (2) a small picture in the Louvre by William Kalff (1621-1693). Here we see a large ‘ginger-jar’ with deep blue ground and white reserves. The porcelain introduced by the Dutch painters is without exception of the blue and white class, and in the earlier works the slaty blue tints are the most common.

But European influence must now and then have made itself felt in China before this time, to judge by some large jars at Dresden decorated with arabesques of unmistakable renaissance type. One of these has been fitted with a lid of Delft ware, made to match the other covers of Chinese origin, and this Dutch-made lid cannot be dated later than the first half of the seventeenth century.99

But it is to the next age that the bulk of the vast collection of blue and white brought together at Dresden by Augustus the Strong belongs. The lange Lijzen, the famous dragon-vases, the large fish-bowls, and the endless series of smaller objects collected by his agents from every side, have made this royal collection a place of pilgrimage for all china maniacs since his day. Not that the general average of the blue and white ware is very high. We find here for the first time specimens of the famous ‘hawthorn ginger-jars’ so dear to later collectors of ‘Nankin china.’ Of course this porcelain did not come from Nankin, the jars were never used for ginger, and the decoration was not derived from the hawthorn—a flower unknown in Chinese art. But it is in these jars that the modern connoisseur, both in England and America, has found the completest expression and highest triumph of the art of the Far East. No words are too strong to express his enthusiasm. We are especially told to look for a certain ‘palpitating quality’ in the blue ground. We hear from Dr. Bushell that these ‘hawthorn jars’ are in China especially associated with the New Year; filled with various objects they are then given as presents. The decoration of prunus flowers (a species allied to our blackthorn) is relieved against a background of ice, and it is the rendering of this crackled ice in varying shades of blue that gives the special cachet to the ware.100