полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

5. Funeral rites

The tribe bury the dead, placing the corpse in the grave with the head to the south. A little rice is buried with the corpse. In Bilāspur the dead are buried in the forest, and the graves of old men are covered with branches of the sāl609 tree. Then they go to a little distance and make a fire, and pour ghī and incense on it as an offering to the ancestors, and when they hear a noise in the forest they take it to be the voice of the dead man. When a man dies his hut is broken down and they do not live in it again. The bodies of children under five are buried either in the house or under the shade of a banyan tree, probably with the idea that the spirit will come back and be born again. They say that a banyan tree is chosen because it lives longest of all trees and is evergreen, and hence it is supposed that the child’s spirit will also live out its proper span instead of being untimely cut off in its next birth.

6. Religion

The Korwas worship Dūlha Deo, the bridegroom god of the Gonds, and in Sargūja their principal deity is Khuria Rāni, the tutelary goddess of the Khuria plateau. She is a bloodthirsty goddess and requires animal sacrifices; formerly at special sacrifices 30 or 40 buffaloes were slaughtered as well as an unlimited number of goats.610 Thākur Deo, who is usually considered a corn-god, dwells in a sacred grove, of which no tree or branch may be cut or broken. The penalty for breach of the rules is a goat, but an exception is allowed if an animal has to be pursued and killed in the grove. Thākur Deo protects the village from epidemic disease such as cholera and smallpox. The Korwas have three festivals: the Deothān is observed on the full moon day of Pūs (December), and all their gods are worshipped; the Nawanna or harvest festival falls in Kunwār (September), when the new grain is eaten; and the Faguwa or Holi is the common celebration of the spring and the new vegetation.

7. Social customs

The Korwas do not admit outsiders into the tribe. They will take food from a Gond or Kawar, but not from a Brāhman. A man is permanently expelled from caste for a liaison with a woman of the impure Gānda and Ghasia castes, and a woman for adultery with any person other than a Korwa. Women are tattooed with patterns of dots on the arms, breasts and feet, and a girl must have this operation done before she can be married. Neither men nor women ever cut their hair.

8. Dancing

Of their appearance at a dance Colonel Dalton states:611 “Forming a huge circle, or rather coil, they hooked on to each other and wildly danced. In their hands they sternly grasped their weapons, the long stiff bow and arrows with bright, broad, barbed heads and spirally-feathered reed shafts in the left hand, and the gleaming battle-axe in the right. Some of the men accompanied the singing on deep-toned drums and all sang. A few scantily-clad females formed the inner curl of the coil, but in the centre was the Choragus who played on a stringed instrument, promoting by his grotesque motions unbounded hilarity, and keeping up the spirit of the dancers by his unflagging energy. Their matted back hair was either massed into a chignon, sticking out from the back of the head like a handle, from which spare arrows depended hanging by the bands, or was divided into clusters of long matted tails, each supporting a spare arrow, which, flinging about as they sprang to the lively movements of the dance, added greatly to the dramatic effect and the wildness of their appearance. The women were very diminutive creatures, on the average a foot shorter than their lords, clothed in scanty rags, and with no ornaments except a few tufts of cotton dyed red taking the place of flowers in the hair, a common practice also with the Santāl girls. Both tribes are fond of the flower of the cockscomb for this purpose, and when that is not procurable, use the red cotton.”

They dance the karma dance in the autumn, thinking that it will procure them good crops, the dance being a kind of ritual or service and accompanied by songs in praise of the gods. If the rains fail they dance every night in the belief that the gods will be propitiated and send rain.

9. Occupation

Of their occupation Colonel Dalton states: “The Korwas cultivate newly cleared ground, changing their homesteads every two or three years to have command of virgin soil. They sow rice that ripens in the summer, vetches, millets, pumpkins, cucumbers—some of gigantic size—sweet potatoes, yams and chillies. They also grow and prepare arrowroot and have a wild kind which they use and sell. They have as keen a knowledge of what is edible among the spontaneous products of the jungle as have monkeys, and have often to use this knowledge for self-preservation, as they are frequently subjected to failure of crops, while even in favourable seasons some of them do not raise sufficient for the year’s consumption; but the best of this description of food is neither palatable nor wholesome. They brought to me nine different kinds of edible roots, and descanted so earnestly on the delicate flavour and nutritive qualities of some of them, that I was induced to have two or three varieties cooked under their instructions and served up, but the result was far from pleasant; my civilised stomach indignantly repelled the savage food, and was not pacified till it had made me suffer for some hours from cold sweat, sickness and giddiness.”612

10. Dacoity

The Korwas in the Tributary States have other resources than these. They are expert hunters, and to kill a bird flying or an animal running is their greatest delight. They do not care to kill their game without rousing it first. They are also very fond of dacoity and often proceed on expeditions, their victims being usually travellers, or the Ahīrs who bring large herds of cattle to graze in the Sargūja forests. These cattle do much damage to the village crops, and hence the Korwas have a standing feud with the herdsmen. They think nothing of murder, and when asked why he committed a murder, a Korwa will reply, ‘I did it for my pleasure’; but they despise both house-breaking and theft as cowardly offences, and are seldom or never guilty of them. The women are also of an adventurous disposition and often accompany their husbands on raids. Before starting they take the omens. They throw some rice before a chicken, and if the bird picks up large solid grains first they think that a substantial booty is intended, but if it chooses the thin and withered grains that the expedition will have poor results. One of their bad omens is that a child should begin to cry before the expedition starts; and Mr. Kunte, who has furnished the above account, relates that on one occasion when a Korwa was about to start on a looting expedition his two-year-old child began to cry. He was enraged at the omen, and picking up the child by the feet dashed its brains out against a stone.

11. Folk-tales

Before going out hunting the Korwas tell each other hunting tales, and they think that the effect of doing this is to bring them success in the chase. A specimen of one of these tales is as follows: There were seven brothers and they went out hunting. The youngest brother’s name was Chilhra. They had a beat, and four of them lay in ambush with their bows and arrows. A deer came past Chilhra and he shot an arrow at it, but missed. Then all the brothers were very angry with Chilhra and they said to him, “We have been wandering about hungry for the whole day, and you have let our prey escape.” Then the brothers got a lot of māhul613 fibre and twisted it into rope, and from the rope they wove a bag. And they forced Chilhra into this bag, and tied up the mouth and threw it into the river where there was a whirlpool. Then they went home. Now Chilhra’s bag was spinning round and round in the whirlpool when suddenly a sāmbhar stag came out of the forest and walked down to the river to drink opposite the pool. Chilhra cried out to the sāmbhar to pull his bag ashore and save him. The sāmbhar took pity on him, and seizing the bag in his teeth pulled it out of the water on to the bank. Chilhra then asked the sāmbhar after he had quenched his thirst to free him from the bag. The sāmbhar drank and then came and bit through the māhul ropes till Chilhra could get out. He then proposed to the sāmbhar to try and get into the bag to see if it would hold him. The sāmbhar agreed, but no sooner had he got inside than Chilhra tied up the bag, threw it over his shoulder and went home. When the brothers saw him they were greatly astonished, and asked him how he had got out of the bag and caught a sāmbhar, and Chilhra told them. Then they killed and ate the sāmbhar. Then all the brothers said to Chilhra that he should tie them up in bags as he had been tied and throw them into the river, so that they might each catch and bring home a sāmbhar. So they made six bags and went to the river, and Chilhra tied them up securely and threw them into the river, when they were all quickly drowned. But Chilhra went home and lived happily ever afterwards.

In this story we observe the low standard of moral feeling noticeable among many primitive races, in the fact that the ingratitude displayed by Chilhra in deceiving and killing the sāmbhar who had saved his life conveys no shock to the moral sense of the Korwas. If the episode had been considered discreditable to the hero Chilhra, it would not have found a place in the tale.

The following is another folk-tale of the characteristic type of fairy story found all over the world. This as well as the last has been furnished by Mr. Narbad Dhanu Sao, Assistant Manager, Uprora:

A certain rich man, a banker and moneylender (Sāhu), had twelve sons. He got them all married and they went out on a journey to trade. There came a holy mendicant to the house of the rich man and asked for alms. The banker was giving him alms, but the saint said he would only take them from his son or son’s wife. As his sons were away the rich man called his daughter-in-law, and she began to give alms to the saint. But he caught her up and carried her off. Then her father-in-law went to search for her, saying that he would not return until he had found her. He came to the saint’s house upon a mountain and said to him, ‘Why did you carry off my son’s wife?’ The saint said to him, ‘What can you do?’ and turned him into stone by waving his hand. Then all the other brothers went in turn to search for her down to the youngest, and all were turned into stone. At last the youngest brother set out to search but he did not go to the saint, but travelled across the sea and sat under a tree on the other side. In that tree was the nest with young of the Raigidan and Jatagidan614 birds. A snake was climbing up the tree to eat the nestlings, and the youngest brother saw the snake and killed it. When the parent birds returned the young birds said, “We will not eat or drink till you have rewarded this boy who killed the snake which was climbing the tree to devour us.” Then the parent birds said to the boy, ‘Ask of us whatever you will and we will give it to you.’ And the boy said,’ I want only a gold parrot in a gold cage.’ Then the parent birds said, “You have asked nothing of us, ask for something more; but if you will accept only a gold parrot in a gold cage wait here a little and we will fly across the sea and get it for you.” So they brought the parrot and cage, and the youngest brother took them and went home. Immediately the saint came to him and asked him for the gold parrot and cage because the saint’s soul was in that parrot. Then the youngest brother told him to dance and he would give him the parrot; and the saint danced, and his legs and arms were broken one after the other, as often as he asked for the parrot and cage. Then the youngest brother buried the saint’s body and went to his house and passed his hands before all the stone images and they all came to life again.

Koshti

1. General notice

Koshti, Koshta, Sālewār.615—The Marātha and Telugu caste of weavers of silk and fine cotton cloth. They belong principally to the Nāgpur and Chhattīsgarh Divisions of the Central Provinces, where they totalled 157,000 persons in 1901, while 1300 were returned from Berār. Koshti is the Marāthi and Sālewār the Telugu name. Koshti may perhaps have something to do with kosa or tasar silk; Sālewār is said to be from the Sanskrit Sālika, a weaver,616 and to be connected with the common word sāri, the name for a woman’s cloth; while the English ‘shawl’ may be a derivative from the same root. The caste suppose themselves to be descended from the famous Saint Mārkandi Rishi, who, they say, first wove cloth from the fibres of the lotus flower to clothe the nakedness of the gods. In reward for this he was married to the daughter of Sūrya, the sun, and received with her as dowry a giant named Bhavāni and a tiger. But the giant was disobedient, and so Mārkandi killed him, and from his bones fashioned the first weaver’s loom.617 The tiger remained obedient to Mārkandi, and the Koshtis think that he still respects them as his descendants; so that if a Koshti should meet a tiger in the forest and say the name of Mārkandi, the tiger will pass by and not molest him; and they say that no Koshti has ever been killed by a tiger. On their side they will not kill or injure a tiger, and at their weddings the Bhāt or genealogist brings a picture of a tiger attached to his sacred scroll, known as Padgia, and the Koshtis worship the picture. A Koshti will not join in a beat for tiger for the same reason; and other Hindus say that if he did the tiger would single him out and kill him, presumably in revenge for his breaking the pact of peace between them. They also worship the Singhwāhini Devi, or Devi riding on a tiger, from which it may probably be deduced that the tiger itself was formerly the deity, and has now developed into an anthropomorphic goddess.

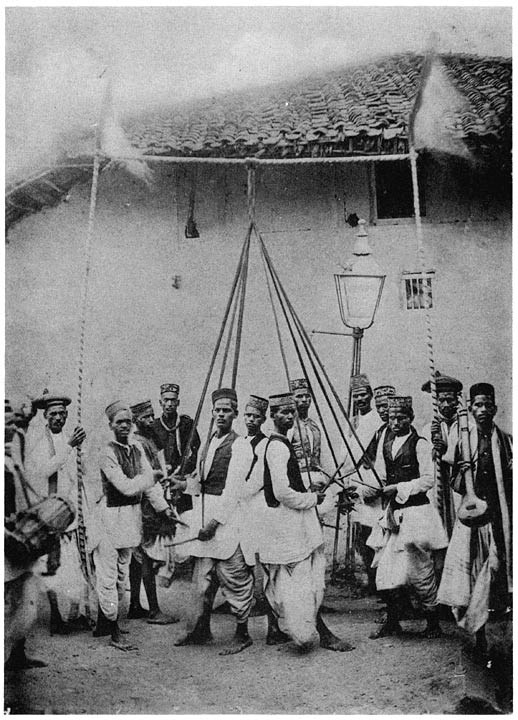

Koshti men dancing a figure, holding strings and beating sticks

2. Subdivisions

The caste have several subdivisions of different types. The Halbis appear to be an offshoot of the primitive Halba tribe, who have taken to weaving; the Lād Koshtis come from Gujarāt, the Gadhewāl from Garha or Jubbulpore, the Deshkar and Martha from the Marātha country, while the Dewangān probably take their name from the old town of that name on the Wardha river. The Patwis are dyers, and colour the silk thread which the weavers use to border their cotton cloth. It is usually dyed red with lac. They also make braid and sew silk thread on ornaments like the separate Patwa caste. And the Onkule are the offspring of illegitimate unions. In Berār there is a separate subcaste named Hatghar, which may be a branch of the Dhangar or shepherd caste. Berār also has a group known as Jain Koshtis, who may formerly have professed the Jain religion, but are now strict Sivites.618 The Sālewārs are said to be divided into the Sūtsāle or thread-weavers, the Padmasāle or those who originally wove the lotus flower and the Sagunsāle, a group of illegitimate descent. The above names show that the caste is of mixed origin, containing a large Telugu element, while a body of the primitive Halbas has been incorporated into it. Many of the Marātha Koshtis are probably Kunbis (cultivators) who have taken up weaving. The caste has also a number of exogamous divisions of the usual type which serve to prevent the marriage of near relatives.

3. Marriage

At a Koshti wedding in Nāgpur, the bride and bridegroom with their parents sit in a circle, and round them a long hempen rope is drawn seven times; the bride’s mother then holds a lamp, while the bridegroom’s mother pours water from a vessel on to the floor. The Sālewārs perform the wedding ceremony at the bridegroom’s house, to which the bride is brought at midnight for this purpose. A display of fireworks is held and the thūn or log of wood belonging to the loom is laid on the ground between the couple and covered with a black blanket. The bridegroom stands facing the east and places his right foot on the thūn, and the bride stands opposite to him with her left foot upon it. A Brāhman holds a curtain between them and they throw rice upon each other’s heads five times and then sit on the log. The bride’s father washes the feet of the bridegroom and gives him a cloth and bows down before him. The wedding party then proceed with music and a display of fireworks to the bridegroom’s house and a round of feasts is given continuously for five days.

The remarriage of widows is freely permitted. In Chānda if the widow is living with her father he receives Rs. 40 from the second husband, but if with her father-in-law no price is given. On the day fixed for the wedding he fills her lap with nuts, cocoanuts, dates and rice, and applies vermilion to her forehead. During the night she proceeds to her new husband’s house, and, emptying the fruit from her lap into a dish which he holds, falls at his feet. The wedding is completed the next day by a feast to the caste-fellows. The procedure appears to have some symbolical idea of transferring the fruit of her womb to her new husband. Divorce is allowed, but is very rare, a wife being too valuable a helper in the Koshti’s industry to be put away except as a last resort. For a Koshti who is in business on his own account it is essential to have a number of women to assist in sizing the thread and fixing it on the loom. A wife is really a factory-hand and a well-to-do Koshti will buy or occasionally steal as many women as he can. In Bhandāra a recent case is known where a man bought a girl and married her to his son and eight months afterwards sold her to another family for an increased price. In another case a man mortgaged his wife as security for a debt and in lieu of interest, and she lived with his creditor until he paid off the principal. Quarrels over women not infrequently result in cases of assault and riot.

4. Funeral customs

Members of the Lingāyat and Kabīrpanthi sects bury their dead and the others cremate them. With the Tirmendār Koshtis on the fifth day the Ayawār priest goes to the cremation-ground accompanied by the deceased’s family and worships the image of Vishnu and the Tulsi or basil upon the grave; and after this the whole party take their food at the place. Mourning is observed during five days for married and three for unmarried persons; and when a woman has lost her husband she is taken on the fifth day to the bank of some river or tank and her bangles are broken, her bead necklace is taken off, the vermilion is rubbed off her forehead, and her foot ornaments are removed; and these things she must not wear again while she is a widow. On the fourth day the Panch or caste elders come and place a new turban on the head of the chief mourner or deceased’s heir; they then take him round the bazār and seat him at his loom, where he weaves a little. After this he goes and sits with the Panch and they take food together. This ceremony indicates that the impurity caused by the death is removed, and the mourners return to common life. The caste do not perform the shrāddh ceremony, but on the Akhātīj day or commencement of the agricultural year a family which has lost a male member will invite a man from some other family of the caste, and one which has lost a female member a woman, and will feed the guest with good food in the name of the dead. In Chhindwāra during the fortnight of Pitripaksh or the worship of ancestors, a Koshti family will have a feast and invite guests of the caste. Then the host stands in the doorway with a pestle and as the guest comes he bars his entrance, saying: ‘Are you one of my ancestors; this feast is for my ancestors?’ To which the guest will reply: ‘Yes, I am your great-grandfather; take away the pestle.’ By this ingenious device the resourceful Koshti combines the difficult filial duty of the feeding of his ancestors with the entertainment of his friends.

5. Religion

The principal deity of the Koshtis is Gajānand or Ganpati, whom they revere on the festival of Ganesh Chathurthi or the fourth day of the month of Bhādon (August). They clean all their weaving implements and worship them and make an image of Ganpati in cowdung to which they make offerings of flowers, rice and turmeric. On this day they do not work and fast till evening, when the image of Ganpati is thrown into a tank and they return home and eat delicacies. Some of them observe the Tīj or third day of every month as a fast for Ganpati, and when the moon of the fourth day rises they eat cakes of dough roasted on a cowdung fire and mixed with butter and sugar, and offer these to Ganpati. Some of the Sālewārs are Vaishnavas and others Lingāyats: the former employ Ayawārs for their gurus or spiritual preceptors and are sometimes known as Tirmendār; while the Lingāyats, who are also called Woheda, have Jangams as their priests. In Bālāghāt and Chhattīsgarh many of the Koshtis belong to the Kabīrpanthi sect, and these revere the special priests of the sect and abstain from the use of flesh and liquor. They are also known as Ghātibandhia, from the ghāt or string of beads of basil-wool (tulsi) which they tie round their necks. In Mandla the Kabīrpanthi Koshtis eat flesh and will intermarry with the others, who are known distinctively as Saktaha. The Gurmukhis are a special sect of the Nāgpur country and are the followers of a saint named Koliba Bāba, who lived at Dhāpewāra near Kalmeshwar. He is said to have fed five hundred persons with food which was sufficient for ten and to have raised a Brāhman from the dead in Umrer. Some Brāhmans wished to test him and told him to perform a miracle, so he had a lot of brass pots filled with water and put a cloth over them, and when he withdrew it the water had changed into curded milk. The Gurmukhis have a descendant of Koliba Bāba for their preceptor, and each of them keeps a cocoanut in his house, which may represent Koliba Bāba or else the unseen deity. To this he makes offerings of sandalwood, rice and flowers. The Gurmukhis are forbidden to venerate any of the ordinary Hindu deities, but they cannot refrain from making offerings to Māta Mai when smallpox breaks out, and if any person has the disease in his house they refrain from worshipping the cocoanut so long as it lasts, because they think that this would be to offer a slight to the smallpox goddess who is sojourning with them. Another sect is that of the Matwāles who worship Vishnu as Nārāyan, as well as Siva and Sakti. They are so called because they drink liquor at their religious feasts. They have a small platform on which fresh cowdung is spread every day, and they bow to this before taking their food. Once in four or five years after a wedding offerings are made to Nārāyan Deo on the bank of a tank outside the village; chickens and goats are killed and the more extreme of them sacrifice a pig, but the majority will not join with these. Offerings of liquor are also made and must be drunk by the worshippers. Mehras and other low castes also belong to this sect, but the Koshtis will not eat with them. But in Chhindwāra it is said that on the day after the Pola festival in August, when insects are prevalent and the season of disease begins, the Koshtis and Māngs go out together to look for the nārbod shrub,619 and here they break a small piece of bread and eat it together. In Bhandāra the Koshtis worship the spirit of one Kadu, patel or headman of the village of Mohali, who was imprisoned in the fort of Ambāgarh under an accusation of sorcery in Marātha times and died there. He is known as Ambagarhia Deo, and the people offer goats and fowls to him in order to be cured of diseases. The above notice indicates that the caste are somewhat especially inclined to religious feeling and readily welcome reformers striving against Hindu polytheism and Brāhman supremacy. This is probably due in part to the social stigma which attaches to the weaving industry among the Hindus and is resented as an injustice by the Koshtis, and in part also to the nature of their calling, which leaves the mind free for thought during long hours while the fingers are playing on the loom; and with the uneducated serious reflection must almost necessarily be of a religious character. In this respect the Koshti may be said to resemble his fellow-weavers of Thrums. In Nāgpur District the Koshtis observe the Muharram festival, and many of them go out begging on the first day with a green thread tied round their body and a beggar’s wallet. They cook the grain which is given to them on the tenth day of the festival, giving a little to the Muhammadan priest and eating the rest. This observance of a Muhammadan rite is no doubt due to their long association with followers of that religion in Berār.