полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

Korku

1. Distribution and origin

Korku.591—A Munda or a Kolarian tribe akin to the Korwas, with whom they have been identified in the India Census of 1901. They number about 150,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār, and belong to the west of the Satpūra plateau, residing only in the Hoshangābād, Nimār, Betūl and Chhindwāra Districts. About 30,000 Korkus dwell in the Berār plain adjoining the Satpūras, and a few thousand belong to Bhopāl. The word Korku means simply ‘men’ or ‘tribesmen,’ koru being their term for a man and kū a plural termination. The tribe have a language of their own, which resembles that of the Kols of Chota Nāgpur. The language of the Korwas, another Munda tribe found in Chota Nāgpur, is also known as Korakū or Korkū, and one of their subcastes has the same name.592 Some Korkus or Mowāsis are found in Chota Nāgpur, and Colonel Dalton considered them a branch of the Korwas. Another argument may be adduced from the sept names of the Korkus which are in many cases identical with those of the Kols and Korwas. There is little reason to doubt then that the Korkus are the same tribe as the Korwas, and both of these may be taken to be offshoots of the great Kol or Munda tribe. The Korkus have come much further west than their kinsmen, and between their residence on the Mahādeo or western Satpūra hills and the Korwas and Kols, there lies a large expanse mainly peopled by the Gonds and other Dravidian tribes, though with a considerable sprinkling of Kols in Mandla, Jubbulpore and Bilāspur. These latter may have immigrated in comparatively recent times, but the Kolis of Bombay may not improbably be another offshoot of the Kols, who with the Korkus came west at a period before the commencement of authentic history.593 One of the largest subdivisions of the Korkus is termed Mowāsi, and this name is sometimes applied to the whole tribe, while the tract of country where they dwell was formerly known as the Mowās. Numerous derivations of this term have been given, and the one commonly accepted is that it signifies ‘The troubled country,’ and was applied to the hills at the time when bands of Koli or Korku freebooters, often led by dispossessed Rājpūt chieftains, harried the rich lowlands of Berār from their hill forts on the Satpūras, exacting from the Marāthas, with poetical justice, the payments known as ‘Tankha Mowāsi’ for the ransom of the settled and peaceful villages of the plains. The fact, however, that the Korkus found in Chota Nāgpur are also known as Mowāsi militates against this supposition, for if the name was applied only to the Korkus of the Satpūra plateau it would hardly have travelled as far east as Chota Nāgpur. Mr. Hislop derived it from the mahua tree. But at any rate Mowāsi meant a robber to Marātha ears, and the forests of Kalībhīt and Melghāt are known as the Mowās.

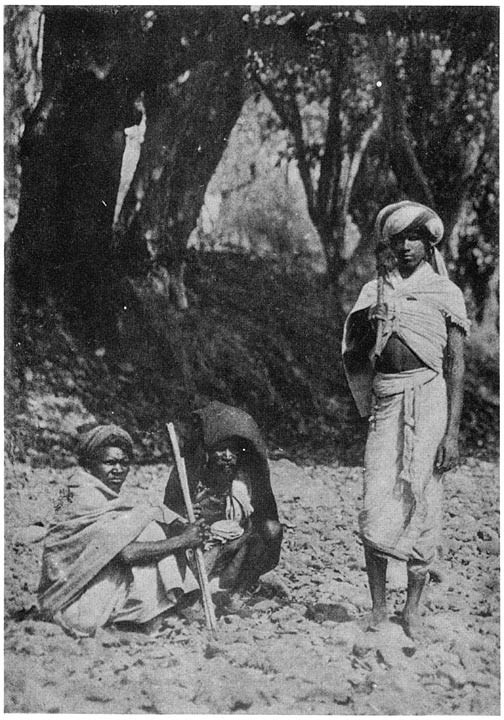

Korkus of the Melghāt hills

2. Tribal legends

According to their own traditions the Korkus like so many other early people were born from the soil. They state that Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, observed that the Vindhyan and Satpūra ranges were uninhabited and besought Mahādeo594 to populate them. Mahādeo despatched his messenger, the crow Kāgeshwar, to find for him an ant-hill made of red earth, and the crow discovered such an ant-hill between the Saolīgarh and Bhānwargarh ranges of Betūl. Mahādeo went to the place, and, taking a handful of red earth, made images in the form of a man and a woman, but immediately two fiery horses sent by Indra rose from the earth and trampled the images to dust. For two days Mahādeo persisted in his attempts, but as often as the images were made they were destroyed in a similar manner. But at length the god made an image of a dog and breathed into it the breath of life, and this dog kept off the horses of Indra. Mahādeo then made again his two images of a man and woman, and giving them human life, called them Mūla and Mūlai with the surname of Pothre, and these two became the ancestors of the Korku tribe. Mahādeo then created various plants for their use, the mahul595 from whose strong and fibrous leaves they could make aprons and head-coverings, the wild plantain whose leaves would afford other clothing, and the mahua, the chironji, the sewan and kullu596 to provide them with food. Time went on and Mūla and Mūlai had children, and being dissatisfied with their condition as compared with that of their neighbours, besought Mahādeo to visit them once more. When he appeared Mūla asked the god to give him grain to eat such as he had heard of elsewhere on the earth. Mahādeo sent the crow Kāgeshwar to look for grain, and he found it stored in the house of a Māng named Japre who lived at some distance within the hills. Japre on hearing what was required besought the honour of a visit from the god himself. Mahādeo went, and Japre laid before him an offering of 12 khandis597 of grain, 12 goats and 12 buckets of water, and invited Mahādeo to eat and drink. The god was pleased with the offering and unwilling to reject it, but considered that he could not eat food defiled by the touch of the outcaste Māng, so Pārvati created the giant Bhīmsen and bade him eat up the food offered to Mahādeo. When Bhīmsen had finished the offering, however, it occurred to him that he also had been defiled by taking food from a Māng, and in revenge he destroyed Japre’s house and covered the site of it with débris and dirt. Japre then complained to Mahādeo of this sorry requital of his offering and prayed to have his house restored to him. Bhīmsen was ordered to do this, and agreed to comply on condition that Mūla should pay to him the same honour and worship as he accorded to Rāwan, the demon king. Mūla promised to do so, and Bhīmsen then sent the crow Kāgeshwar to the tank Daldal, bidding him bring thence the pig Buddu, who being brought was ordered to eat up all the dirt that covered Japre’s house. Buddu demurred except on condition that he also should be worshipped by Mūla and his descendants for ever. Mūla agreed to pay worship to him every third year, whereupon Buddu ate up all the dirt, and dying from the effects received the name of Mahābissum, under which he is worshipped to the present day. Mahādeo then took some seed from the Māng and planted it for Mūla’s use, and from it sprang the seven grains—kodon, kutki, gurgi, mandgi, barai, rāla and dhān598 which the Korkus principally cultivate. It may be noticed that the story ingeniously accounts for and sheds as it were an orthodox sanction on the custom of the Korkus of worshipping the pig and the local demon Bhīmsen, who is placed on a sort of level with Rāwan, the opponent of Rāma. After recounting the above story Mr. Crosthwaite remarks: “This legend given by the Korkus of their creation bears a curious analogy to our own belief as set forth in the Old Testament. They even give the tradition of a flood, in which a crow plays the part of Noah’s dove. There is a most curious similarity between their belief in this respect and that found in such distant and widely separated parts as Otaheite and Siberia. Remembering our own name ‘Adam,’ which I believe means in Hebrew ‘made of red earth,’ it is curious to observe the stress that is laid in the legend on the necessity for finding red earth for the making of man.” Another story told by the Korkus with the object of providing themselves with Rājpūt ancestry is to the effect that their forefathers dwelt in the city of Dhārānagar, the modern Dhār. It happened one day that they were out hunting and followed a sāmbhar stag, which fled on and on until it finally came to the Mahādeo or Pachmarhi hills and entered a cave. The hunters remained at the mouth waiting for the stag to come out, when a hermit appeared and gave them a handful of rice. This they at once cooked and ate as they were hungry from their long journey, and they found to their surprise that the rice sufficed for the whole party to eat their fill. The hermit then told them that he was the god Mahādeo, and had assumed the form of a stag in order to lead them to these hills, where they were to settle and worship him. They obeyed the command of the god, and a Korku zamīndār is still the hereditary guardian of Mahādeo’s shrine at Pachmarhi. This story has of course no historical value, and the Korkus have simply stolen the city of Dhārānagar for their ancestral home from their neighbours the Bhoyars and Panwārs. These castes relate similar stories, which may in their case be founded on fact.

3. Tribal subdivisions

As is usual among the forest tribes the Korkus formerly had a subdivision called Rāj-Korkū, who were made up of landowning members of the caste and were admitted to rank among those from whom a Brāhman would take water, while in some cases a spurious Rājpūt ancestry was devised for them, as in the story given above. The remainder of the tribe were called Potharia, or those to whom a certain dirty habit is imputed. These main divisions have, however, become more or less obsolete, and have been supplanted by four subcastes with territorial names, Mowāsi, Bāwaria, Rūma and Bondoya. The meaning of the term Mowāsi has already been given, and this subcaste ranks as the highest, probably owing to the gentlemanly calling of armed robbery formerly practised by its members. The Bāwarias are the dwellers in the Bhānwargarh tract of Betūl, the Rūmas those who belong to Bāsim and Gangra in the Amraoti District, and the Bondoyas the residents of the Jītgarh and Pachmarhi tract. These last are also called Bhovadāya and Bhopa, and this name has been corrupted into Bopchi in the Wardha District, a few hundred Bondoya Korkus who live there being known as Bopchi and considered a distinct caste. Except among the Mowāsis, who usually marry in their own subcaste, the rule of endogamy is not strictly observed. The above description refers to Betūl and Nimār, but in Hoshangābād, Mr. Crosthwaite says: “Four-fifths of the Korkus have been so affected by the spread of Brāhmanical influence as to have ceased to differ in any marked way from the Hindu element in the population, and the Korku has become so civilised as to have learnt to be ashamed of being a Korku.” Each subcaste has traditionally 36 exogamous septs, but the numbers have now increased. The sept names are generally taken from those of plants and animals. These were no doubt originally totemistic, but the Korkus now say that the names are derived from trees and other articles in or behind which the ancestors of each sept took refuge after being defeated in a great battle. Thus the ancestor of the Atkul sept hid in a gorge, that of the Bhūri Rāna sept behind a dove’s nest, that of the Dewda sept behind a rice plant, that of the Jāmbu sept behind a jāmun tree,599 that of the Kāsada sept in the bed of a river, that of the Tākhar sept behind a cucumber plant, that of the Sakum sept behind a teak tree, and so on. Other names are Banku or a forest-dweller; Bhūrswa or Bhoyar, perhaps from the caste of that name; Basam or Baoria, the god of beehives; and Marskola or Mawāsi, which the Korkus take to mean a field flooded by rain. One sept has the name Killībhasam, and its ancestor is said to have eaten the flesh of a heifer half-devoured by a tiger and parched by a forest fire. In Hoshangābād the legend of the battle is not known, and among the names given by Mr. Crosthwaite are Akandi, the benighted one; Tandil, a rat; and Chuthar, the flying black-bug. In a few cases the names of septs are Hindi or Marāthi words, these perhaps affording a trace of the foundation of separate families by members of other castes. No totemistic usages are followed as a rule, but one curious instance may be given. One sept has the name lobo, which means a piece of cloth. But the word lobo also signifies ‘to leak.’ If a person says a sentence containing the word lobo in either signification before a member of the sept while he is eating, he will throw away the food before him as if it were contaminated and prepare a meal afresh. Ten of the septs600 consider the regular marriage of girls to be inauspicious, and the members of these simply give away their daughters without performing a ceremony.

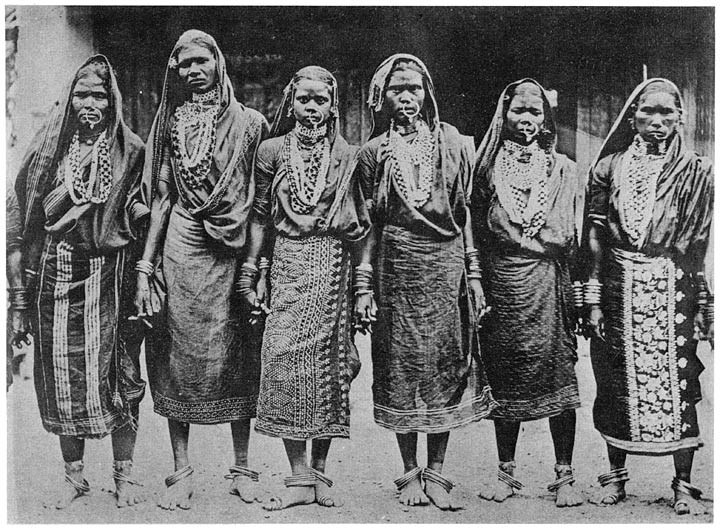

Korku women in full dress

4. Marriage Betrothal

Marriage between members of the same sept is prohibited and also the union of first cousins. The preliminaries to a marriage commence with the bāli-dūdna or arrangement of the match. The boy’s father having selected a suitable bride for his son sends two elders of the caste to propose the match to her father, who as a matter of etiquette invariably declines it, swearing with great oaths that he will not allow his daughter to get married or that he will have a son-in-law who will serve for her. The messengers depart, but return again and again until the father’s obduracy is overcome, which may take from six months to two years, while from nine to twelve months is considered a respectable period. When his consent is finally obtained the residents of the girl’s village are called to hear it, and the compact is sealed with large potations of liquor. A ceremony of betrothal follows at which the daij or dowry is arranged, this signifying among the Korkus the compensation to be paid to the girl’s father for the loss of her services. It is computed by a curious system of symbolic higgling. The women of the girl’s party take two plates and place on them two heaps containing respectively ten and fifty seeds of a sort used for reckoning. The ten seeds on the first plate represent five rupees for the panchāyat and five cloths for the mother, brother, paternal aunt and paternal and maternal uncles of the girl. The heap of fifty seeds indicates that Rs. 50 must be paid to the girl’s father. When the plates are received by the boy’s party they take away forty-five of the seeds from the larger heap and return the plate, to indicate that they will only pay five rupees to the girl’s father. The women add twenty-five seeds and send back the plate again. The men then take away fifteen, thus advancing the bride-price to fifteen rupees. The women again add twenty-five seeds and send back the plate, and the men again take away twenty, and returning the remaining twenty which are taken as the sum agreed upon, in addition to the five cloths and five rupees for the panchāyat. The total amount paid averages about Rs. 60. Wealthy men sometimes refuse this payment or exchange a bride for a bridegroom. The dowry should be paid before the wedding, and in default of this the bridegroom’s father is made not a little uncomfortable at that festival. Should a betrothed girl die before marriage, the dowry does not abate and the parents of the girl have a right to stop her burial until it is paid. But if a father shows himself hard to please and refuses eligible offers, or if a daughter has fallen in love, as sometimes happens, she will leave her home quietly some morning and betake herself to the house of the man of her choice. If her young affections have not been engaged, she may select of her own accord a protector whose circumstances and position make him attractive, and preferably one whose mother is dead. Occasionally a girl will install herself in the house of a man who does not want her, and his position then is truly pitiable. He dare not turn her out as he would be punished by the caste for his want of gallantry, and his only course is to vacate his own house and leave her in possession. After a time his relations represent to her that the man she wants has gone on a journey and will not be back for a long time, and induce her to return to the paternal abode. But such a case is very rare.

5. The marriage ceremony

The marriage ceremony resembles that of the Hindus but has one or two special features. After the customary cleaning of the house which should be performed on a Tuesday, the bridegroom is carried to the heap of stones which represents Mutua Deo, and there the Bhumka or priest invokes the various sylvan deities, offering to them the blood of chickens. Again when he is dressed for the wedding the boy is given a knife or dagger carrying a pierced lemon on the blade, and he and his parents and relatives proceed to a ber601 or wild plum tree. The boy and his parents sit at the foot of the tree and are tied to it with a thread, while the Bhumka again spills the blood of a fowl on the roots of the tree and invokes the sun and moon, whom the Korkus consider to be their ultimate ancestors. The ber fruit may perhaps be selected as symbolising the red orb of the setting sun. The party then dance round the tree. When the wedding procession is formed the following ceremony takes place: A blanket is spread in the yard of the house and the bridegroom and his elder brother’s wife are made to stand on it and embrace each other seven times. This may probably be a survival of the modified system of polyandry still practised by the Khonds, under which the younger brothers are allowed access to the elder brother’s wife until their own marriage. The ceremony would then typify the cessation of this intercourse at the wedding of the boy. The procession must reach the bride’s village on a Monday, a Wednesday or a Friday, a breach of this rule entailing a fine of Rs. 8 on the boy’s father. On arrival at the bride’s village its progress is barred by a rope stretched across the road by the bride’s relatives, who must be given two pice each before it is removed. The bridegroom touches the marriage-shed with a bamboo fan. Next day the couple are seated in the shed and covered with a blanket on to which water is poured to symbolise the fertilising influence of rain. The groom ties a necklace of beads to the girl’s neck, and the couple are then lifted up by the relatives and carried three times round the yard of the house, while they throw yellow-coloured rice at each other. Their clothes are tied together and they proceed to make an offering to Mutua Deo. In Hoshangābād, Mr. Crosthwaite states, the marriage ceremony is presided over by the bridegroom’s aunt or other collateral female relative. The bride is hidden in her father’s house. The aunt then enters carrying the bridegroom and searches for the bride. When the bride is found the brother-in-law of the bridegroom takes her up, and bride and bridegroom are then seated under a sheet. The rings worn on the little finger of the right hand are exchanged under the sheet and the clothes of the couple are knotted together. Then follow the sapta padi or seven steps round the post, and the ceremony concludes with a dance, a feast and an orgy of drunkenness. A priest takes no part in a Korku marriage ceremony, which is a purely social affair. If a man has only one daughter, or if he requires an assistant for his cultivation, he often makes his prospective son-in-law serve for his wife for a period varying from five to twelve years, the marriage being then celebrated at the father-in-law’s expense. If the boy runs away with the girl before the end of his service, his parents have to pay to the girl’s father five rupees for each year of the unexpired term. Marriage is usually adult, girls being wedded between the ages of ten and sixteen and boys at about twenty. Polygamy is freely practised by those who are well enough off to afford it, and instances are known of a man having as many as twelve wives living. A man must not marry his wife’s younger sister if she is the widow of a member of his own sept nor his elder brother’s widow if she is his wife’s elder sister. Widow-marriage is allowed, and divorce may be effected by a simple proclamation of the fact to the panchāyat in a caste assembly.

6. Religion

The Korkus consider themselves as Hindus, and are held to have a better claim to a place in the social structure of Hinduism than most of the other forest tribes, as they worship the sun and moon which are Hindu deities and also Mahādeo. In truth, however, their religion, like that of many low Hindu castes, is almost purely animistic. The sun and moon are their principal deities, the name for these luminaries in their language being Gomaj, which is also the term for god or a god. The head of each family offers a white she-goat and a white fowl to the sun every third year, and the Korkus stand with the face to the sun when beginning to sow, and perform other ceremonies with the face turned to the east. The moon has no special observances, but as she is a female deity she is probably considered to participate in those paid to the sun. These gods are, however, scarcely expected to interest themselves in the happenings of a Korku’s daily life, and the local godlings who are believed to regulate these are therefore propitiated with greater fervour. The three most important village deities are Dongar Deo, the god of the hills, who resides on the nearest hill outside the village and is worshipped at Dasahra with offerings of cocoanuts, limes, dates, vermilion and a goat; Mutua Deo, who is represented by a heap of stones within the village and receives a pig for a sacrifice, besides special oblations when disease and sickness are prevalent; and Māta, the goddess of smallpox, to whom cocoanuts and sweetmeats, but no animal sacrifices, are offered.

7. The Bhumka

The priests of the Korkus are of two kinds—Parihārs and Bhumkas. The Parihār may be any man who is visited with the divine afflatus or selected as a mouthpiece by the deity; that is to say, a man of hysterical disposition or one subject to epileptic fits. He is more a prophet than a priest, and is consulted only on special occasions. Parihārs are also rare, but every village has its Bhumka, who performs the regular sacrifices to the village gods and the special ones entailed by disease or other calamities. On him devolves the dangerous duty of keeping tigers out of the boundaries. When a tiger visits the village the Bhumka repairs to Bāgh Deo602 and makes an offering to the god, promising to repeat it for so many years on condition that the tiger does not appear for that time. The tiger on his part never fails to fulfil the contract thus silently made, for he is pre-eminently an honourable upright beast, not faithless and treacherous like the leopard whom no contract can bind. Some Bhumkas, however, masters of the most powerful spells, are not obliged to rely on the traditional honour of the tiger, but compel his attendance before Bāgh Deo; and such a Bhumka has been seen as a very Daniel among tigers muttering his incantations over two or three at a time as they crouched before him. Of one Bhumka in Kālibhīt it is related that he had a fine large sāj tree, into which, when he uttered his spells, he would drive a nail, and on this the tiger came and ratified the compact with his enormous paw, with which he deeply scored the bark. In this way some have lost their lives, victims of misplaced confidence in their own powers.603 If a man is sick and it is desired to ascertain what god or spirit of an ancestor has sent the malady, a handful of grain is waved over the sick man and then carried to the Bhumka. He makes a heap of it on the floor, and, sitting over it, swings a lighted lamp suspended by four strings from his fingers. He then repeats slowly the name of the village deities and the sick man’s ancestors, pausing between each, and the name at which the lamp stops swinging is that of the offended one. He then inquires in a similar manner whether the propitiation shall be a pig, a chicken, a goat, a cocoanut and so on. The office of Bhumka is usually, but not necessarily, hereditary, and a new one is frequently chosen by lot, this being also done when a new village is founded. All the villagers then sit in a line before the shrine of Mutua Deo, to whom a black and a white chicken are offered. The Parihār, or, if none be available, the oldest man present, then sets a pai604 rolling before the line of men, and the person before whom it stops is marked out by this intervention of the deity as the new Bhumka. When a new village is to be founded a pai measure is filled with grain to a level with the brim, but with no head (this being known as a mundi or bald pai), and is placed before Mutua Deo in the evening and watched all night. In the morning the grain is poured out and again replaced in the measure; if it now fills this and also leaves enough for a head, and still more if it brims and runs over, it is a sign that the village will be very prosperous and that every cultivator’s granaries will run over in the same way. But it is an evil omen if the grain does not fill up to the level of the rim of the measure. The explanation of the difference in bulk may be that the grains increase or decrease slightly in size according as the atmosphere is moist or dry, or perhaps the Bhumka works the oracle. The Bhumka usually receives contributions in grain from all the houses in the village; but occasionally each cultivator gives him a day’s ploughing, a day’s weeding and a day’s wood-cutting free. The Bhumka is also employed in Hindu villages for the service of the village gods. But the belief in the powers of these deities is decaying, and with it the tribute paid to the Bhumka for securing their favour. Whereas formerly he received substantial contributions of grain on the same scale as a village menial, the cultivator will now often put him off with a basketful or even a handful, and say, ‘I cannot spare you any more, Bhumka; you must make all the gods content with that.’ In curing diseases the Parihār resorts to swindling tricks. He will tell the sick man that a sacrifice is necessary, asking for a goat if the patient can afford one. He will say it must be of a particular colour, as all black, white or red, so that the sick man’s family may have much trouble in finding one, and they naturally think the sacrifice is more efficacious in proportion to the difficulty they experience in arranging for it. If they cannot afford a goat the Parihār tells them to sacrifice a cock, and requires one whose feathers curl backwards, as they occasionally do. If the family is very poor any chicken which has come out of the shell, so long as it has a beak, will do duty for a cock. If a man has a pain in his body the Parihār will suck the place and produce small pieces of bone from his mouth, stained with vermilion to imitate blood, and say that he has extracted them from the patient’s body. Perhaps the idea may be that the bones have been caused to enter his body and make him ill by the practice of magic. Formerly the Parihār had to prove his supernatural powers by whipping himself on the back with a rope into which the ends of nails were twisted, and to continue this ordeal for a period long enough to satisfy the villagers that he could not have borne it without some divine assistance. But this salutary custom has fallen into abeyance.