полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

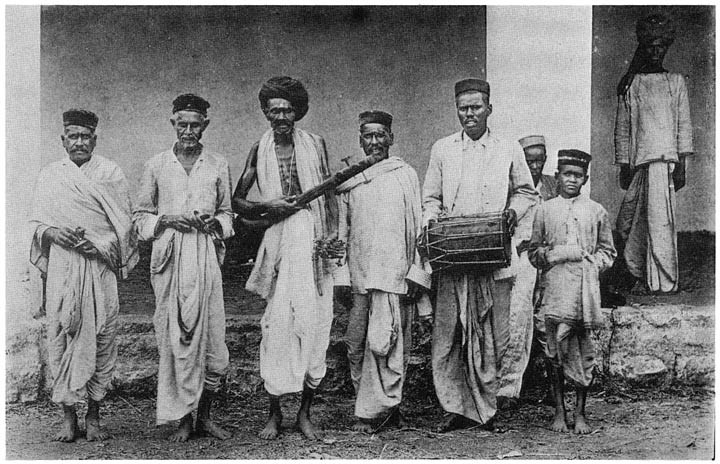

Group of Gurao musicians with their instruments

6. Funeral customs

The dead are burnt and the ashes thrown into water or carried to the Ganges. A small piece of gold, two or three small pearls, and some basil leaves are put into the mouth, and flowers, red powder and betel leaves are spread over the corpse. The son or male heir of the deceased walks in front carrying fire in an earthen pot. At a small distance from the burning-ground, when the bearers change places, he picks up a stone, known as the life-stone or jivkhada. This is afterwards buried at the burning-ghāt until the priest comes to effect the purification of the mourners on the tenth day. It is then dug up, set up and worshipped, and thrown into a well. A man is burnt naked; a woman in a robe and bodice. The heads of widows are not shaved as a rule, but on the tenth day after her husband’s death a widow is asked whether she would like her head shaved; if she refuses, the people conclude that she intends to marry again. But if the deceased left no male heir to carry behind his bier the burning wood with which the funeral pyre is to be kindled, then the widow must be shaved before the funeral starts and perform this duty. If there is no male relative and no widow, the pot containing fire is tied to the bier. When the corpse of a woman who has died in child-bed is being carried to the burning-ground various rites are observed to prevent her spirit from becoming a Churel and troubling the living. A lemon charmed by a magician is buried under the corpse and a man follows the body strewing the seeds of rala, while nails are driven into the threshold of the house.137

7. Social position

The caste has now a fairly high social status and ranks above the Kunbis. They abstain from all flesh and from liquor and will take food only from the hands of a Marātha Brāhman, while Kunbis and other cultivating and serving castes will accept food from their hands. They worship Siva principally on Mondays, this day being sacred to the deity, who carries the moon as an ornament on his head, crowning the matted locks from which the Ganges flows.

8. The Jain Guraos

Of the Jain Guraos Mr. Enthoven quotes the following interesting description from the Bombay Gazetteer: “They are mainly servants in village temples which, though dedicated to Brāhmanic gods, have still by their sides broken remains of Jain images. This, and the fact that most of the temple land-grants date from a time when Jainism was the State religion, support the theory that the Jain Guraos are probably Jain temple servants who have come under the influence partly of Lingāyatism and partly of Brāhmanism. A curious survival of their Jainism occurs at Dasahra, Shimga and other leading festivals, when the village deity is taken out of the temple and carried in procession. On these occasions, in front of the village god’s palanquin, three, five or seven of the villagers, among whom the Gurao is always the leader, carry each a long, gaily-painted wooden pole resting against their right shoulder. At the top of the pole is fastened a silver mask or hand and round it is draped a rich silk robe. Of these poles, the chief one, carried by the Gurao, is called the Jain’s pillar, Jainācha khāmb.”

Halba

1. Traditions of the caste

Halba, Halbi.138—A caste of cultivators and farmservants whose home is the south of the Raipur District and the Kānker and Bastar States; from here small numbers of them have spread to Bhandāra and parts of Berār. In 1911 they numbered 100,000 persons in the combined Provinces. The Halbas have several stories relating to their own origin. One of these, reported by Mr. Gokul Prasād, is as follows: One of the Uriya Rājas had erected four scarecrows in his field to keep off the birds. One night Mahādeo and Pārvati were walking on the earth and happened to pass that way, and Pārvati saw them and asked what they were. When it was explained to her she thought that as they had excited her interest something should be done for them, and at her request Mahādeo gave them life and they became two men and two women. Next morning they presented themselves before the Rāja and told him what had happened. The Rāja said, “Since you have come on earth, you must have a caste. Run after Mahādeo and find out what caste you should belong to.” So they ran after the god and inquired of him, and he said that as they had excited his and Pārvati’s attention by waving in the wind they should be called Halba, from halna, to wave. This story is clearly based on one of those fanciful punning derivations so dear to the Brāhmanical mind, but the legend about being created from scarecrows is found among other agricultural castes of non-Aryan origin, as the Lodhis. The story continues that the reason why the Halbas came to settle in Bastar and Kānker was that they had accompanied one of the Rājas of Jagannāth in Orissa, who was afflicted with leprosy, to the Sihāwa jungles, where he proposed to pass the rest of his life in retirement. On a certain day the Rāja went out hunting with his dogs, one of which was quite white. This dog jumped into a spring of water and came out with his white skin changed to copper red. The Rāja, observing this miracle, bathed in the spring himself and was cured of his leprosy. He then wished to return to Orissa, but the Halbas induced him to remain in his adopted country, and he became the ancestor of the Rājas of Kānker. The Halbas are still the household servants of the Kānker family, and when a fresh chief succeeds, one of them, who has the title of Kapardār, takes him to the temple and invests him with the Durbār kī poshak or royal robes, affixing also the tīka or badge of office on his forehead with turmeric, rice and sandalwood, and rubbing his body over with ottar of roses. Until lately the Kapardār’s family had a considerable grant of rent-free land, but this has now been taken away. A Halba is or was also the priest of the temple at Sihāwa, which is said to have been built by the first Rāja over the spring where he was healed of his leprosy. The Halbas are also connected with the Rājas of Bastar, and a suggestion has been made139 that they originally belonged to the Telugu country and came with the Rājas of Bastar from Warangal in the Deccan. Mr. Gilder derives the name from an old Canarese word Halbar or Halbaru, meaning ‘old ones or ancients’ or ‘primitive inhabitants.’ The Halba dialect, however, contains no traces of Canarese, and on the question of their entering Bastar with the Rājas, Rai Bahādur Panda Baijnāth, Diwān of Bastar, writes as follows: In the following saying relating to the coming of the Bastar Rājas, which is often repeated, the Halba’s name does not occur:

Which may be rendered: “The Rāja was of the Chalki race.140 The drum was called Dibdibi. Kosaria Rāwat, Pita Bhatra, Peng Parja and Rāja Muria,141 these four castes came with the Rāja. The tribute paid (to the Rāja) was a comb of tendu wood and a lava quail.” This doggerel rhyme is believed to recall the circumstances of the immigration of the Bastar Rājas. So the Halbas did not perhaps come with the Rāja, but they were his guards for a long time. In the Dasahra ceremony a Halba carried the royal Chhatra or Umbrella, and the Rāja walked under the protection of another Halba’s naked sword. A Halba’s widows were not sold and his intestate property was not taken over by the Rāja.

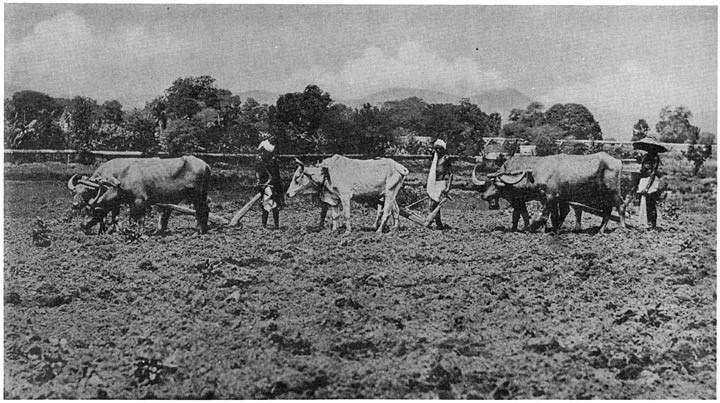

Ploughing with cows and buffaloes in Chhattīsgarh

2. Halba landowners in Bastar and Bhandāra

Thus the Halbas occupy a comparatively honourable position in Bastar. They are the highest local caste with the exception of the Brāhmans, the Dhākars or illegitimate descendants of Brāhmans, and a few Rājpūt families. The reason for this is no doubt that they have become landholders in the State, a position which it would not be difficult for them to acquire when their only rivals were the Gonds. They are moderately good cultivators, and in Dhamtari can hold their own with Hindus, so that they could well surpass the Gond. Traditions also remain in Bastar of a Halba revolt. It is said that during Rāja Daryao Deo’s reign, about 125 years back, the Halbas rebelled and many were thrown down a waterfall ninety feet high, one only of these escaping with his life. The eyes of some were also put out as a punishment for the oppression they had exercised, and a stone inscription at Donger records the oath of fealty taken by the Halbas before the image of Danteshwari, the tutelary deity of Bastar, after their insurrection was put down in Samvat 1836 or A.D. 1779. The Halbas were thus a caste of considerable influence, since they could attempt to subvert the ruling dynasty. In Bhandāra again the caste have quite a different story, and say that they came from the United Provinces or, according to another version, the Makrai State, where they were of the status of Rājpūts and wore the sacred thread. There a girl of their family, of great beauty, was asked in marriage by a Muhammadan king. The father could not refuse the king, but would not give his daughter in marriage to one not of his own caste. So he fled south and took asylum with the Gond Rāja of Chānda, from whom the Halba zamīndārs subsequently received their estates. It seems unnecessary to attach any importance to this story; the tale of the beautiful daughter is most hackneyed, and the whole has probably been devised by the Brāhmans to give the Halba zamīndārs of Bhandāra a more respectable ancestry than they could claim if they admitted having come from Bastar, certainly no home of Rājpūts. But if this supposition is correct it is interesting to note how a legend may show a caste as originating in some place with which it never had any connection whatever; and it seems a necessary conclusion that no importance can be attached to such traditions without corroborating evidence.

3. Internal structure: subcastes

The caste have local divisions known as Bastarha, Chhattīsgarhia and Marethia, according as they live in Bastar, Chhattīsgarh, or Bhandāra and the other Marātha Districts. The last two groups, however, intermarry, so only the Bastar Halbas really form a separate subcaste. But the caste is also everywhere divided into two groups of pure and mixed Halbas. These are known in Bastar and Chhattīsgarh as Purāit or Nekha, and Surāit or Nāyak, respectively, and in Bhandāra as Barpangat and Khālpangat or those of good and bad stock. The Surāits or Khālpangats are said to be of mixed origin, born from Halba fathers and women of other castes. But in past times unions of Halba mothers and men of other castes were perhaps not less frequent. These two sets of groups do not intermarry. A Surāit Halba will take food from a Purāit, but the Purāits do not return the compliment; though in some localities they will accept food which does not contain salt. The two divisions will take water from each other and exchange leaf-pipes. In Bhandāra the Barpangat or pure Halbas have now further split into two groups, the zamīndāri families having constituted themselves into a separate subdivision; they practise hypergamy with the others, taking daughters from them in marriage but not giving their daughters to them. This is simply of a piece with their claim to be Rājpūts, hypergamy being a custom of northern India.

4. Exogamous sections

The exogamous sections of the caste afford further evidence of their mixed origin. Many of the names recorded are those of other castes, as Baretha (a washerman), Bhoyar (Bhoi or bearer), Rāwat (herdsman), Barhai (carpenter), Mālia (Māli or gardener), Dhākar (Vidūr or illegitimate Brāhman), Bhandāri (barber), Pardhān (Gond), Mānkar (title of various tribes), Sahara (Saonr), Kanderi (turner), Agri (Agarwāla Bania), Baghel (a sept of Rājpūts), Elmia (from Velama, Telugu cultivators), and Chalki and Ponwār (Chalukya and Panwār Rājpūts). It may be concluded that these groups are descended from ancestors of the caste after which they are named. There are also a number of territorial and titular names of the usual type, and many totemistic names, as Ghorapatia (a horse), Kawaliha (lotus), Aurila (tamarind), Lendia (a tree), Gohi (a lizard), Manjur (a peacock), Bhringrāj (a blackbird) and so on. In Bastar they revere the animal or plant after which their sept is named and will not kill or injure it. If a man accidentally kills his devak or sacred animal he will tear off a small piece of his cloth and throw it away to make a shroud for the corpse. A few of them will break their earthen pots as if a relative had died in their house, but this is not general. In Bastar the totemistic groups are named barags, and many men also belong to a thok, having some titular name which they use as a surname. Nowadays marriage is avoided by persons having the same thok or surname as well as between those of the same barag.

5. Theory of the origin of the caste

In view of the information available the most probable theory of the origin of the Halbas is that they were a mixed caste, born of irregular alliances between the Uriya Rājas and their retainers with the women of their household servants and between the different servants themselves. Mr. Gokul Prasād points out that many of the names of Halba sections are those of the haguas or household menials of the Uriya chiefs. The Halbas, according to their own story, came here in attendance on one of the chiefs, and are still employed as household servants in Kānker and Bastar. They are clearly a caste of mixed origin as they still admit women of other castes married by Halba men into the community, and one of their two subcastes in each locality consists of families of impure descent. The Dhākars of Bastar are the illegitimate offspring of Brāhmans with women of the country who have grown into a caste, and Mr. Panda Baijnāth quotes a proverb, saying that ‘The Halbas and Dhākars form two portions of a bedsheet.’ Instances of other castes similarly formed are the Audhelias of Bilāspur, who are said to be the offspring of Daharia Rājpūts by their kept women, and the Bargāhs, descended from the nurses of Rājpūt families. The name Halba might be derived from hal, a plough, and be a variant for harwāha, the common term for a farmservant in the northern Districts. This derivation they give themselves in one of their stories, saying that their first ancestor was created from a sod of earth on the plough of Balarām or Haladhara, the brother of Krishna; and it has also the support of Sir G. Grierson. The caste includes no doubt a number of Gonds, Rāwats (herdsmen) and others, and it may be partly occupational, consisting of persons employed as farmservants by the Hindu settlers. The farmservant in Chhattīsgarh has a very definite position, his engagement being permanent and his wages consisting always in a fourth share of the produce, which is divided among them when several are employed. The caste have a peculiar dialect of their own, which Dr. Grierson describes as follows:142 “Linguistic evidence also points to the fact that the Halbas are an aboriginal tribe, who have adopted Hinduism and an Aryan language. Their dialect is a curious mixture of Uriya, Chhattīsgarhi and Marāthi, the proportions varying according to the locality. In Bhandāra it is nearly all Marāthi, but in Bastar it is much more mixed and has some forms which look like Telugu.” If the home of the Halbas was in the debateable land between Chhattīsgarh and the Uriya country to the east and south of the Mahānadi, their dialect might, as Mr. Hīra Lāl points out, have originated here. They themselves give the ruined but once important city of Sihāwa on the banks of the Mahānadi in this tract as that of their first settlement; and Uriya is spoken to the east of Sihāwa and Marāthi to the west, while Chhattīsgarhi is the language of the locality itself and of the country extending north and south. Subsequently the Halbas served as soldiers in the armies of the Ratanpur kings and their position no doubt considerably improved, so that in Bastar they became an important landholding caste. Some of these soldiers may have migrated west and taken service under the Gond kings of Chānda, and their descendants may now be represented by the Bhandāra zamīndārs, who, however, if this theory be correct, have entirely forgotten their origin. Others took up weaving and have become amalgamated with the Koshti caste in Bhandāra and Berār.

6. Marriage

Girls are not usually married until they are above ten years old, or nearly adult as age goes in India; but there is no rule on the subject. Many girls reach twenty without entering wedlock. If the parents are too poor to pay for their daughter’s marriage the neighbours will subscribe. In Bastar, however, the Uriya custom prevails, and an unmarried girl in whom the signs of puberty appear is put out of caste. In such a case her father marries her to a mahua tree. The strictness of the rule on this subject among the Uriyas is probably due to the strength of Brāhmanical influence, the priestly caste possessing more power and property in Sambalpur and Orissa than in almost any part of India. If a death occurs in the family of the bridegroom just before the date fixed for the wedding, and the ceremonies of purification cannot be completed prior to it, the bride is formally wedded to an achar143 or mahua tree;144 the marriage crown is tied on to the tree, and the bride walks round it seven times. After the bridegroom’s purification the couple are taken to the same tree, and here the forehead of the bridegroom is marked with turmeric paste and rice. The couple sit one on each side of the tree, and the Tikāwan ceremony or presentation of gifts by the relatives and friends is performed, and the marriage is considered to be complete. If an unmarried girl goes wrong with an outsider of low caste she is expelled from the community; but if with a member of a caste from whom a Halba can take water she may be readmitted to caste, provided she has not eaten food cooked in an earthen pot from the hands of her seducer; but not if she has done so. If there be a child of the seducer she must wait until it be weaned and either taken by the putative father or given away to a Chamār or Gond. The girl can then be given in marriage to any Halba as a widow. Women of other castes married by Halbas are admitted into the community. This happens most frequently in the case of women of the Rāwat (herdsman) caste.

7. Importance of the sister’s son

A match which is commonly arranged where practicable is that of a brother’s daughter to a sister’s son. And a man always shows a special regard and respect for his sister’s son, touching his feet as to a superior, while, whenever he desires to make a gift as an offering of thanks or atonement or as a meritorious action, the sister’s son is the recipient. At his death he usually leaves a substantial legacy, such as one or two buffaloes, to his sister’s son, the remainder of the property going to his own family. This recognition of a special relationship is probably a survival of the matriarchate, when property descended through women, and a sister’s son would be his uncle’s heir. Thus a man would naturally desire to marry his daughter to his nephew in order that she might participate in his property, and hence arose the custom of making this match, which is still the most favoured among the Halbas and Gonds, though the reasons which led to it have been forgotten for several centuries.

8. The wedding ceremony

Matches are usually arranged on the initiative of the boy’s father through a mutual friend who resides in the girl’s village, and is known as the Mahālia or matchmaker. When the contract is concluded the boy’s father sends a present of fixed quantities of grain to the girl, which are in the nature of a bride-price, and subsequently on an auspicious day selected by the family priest he and his friends proceed to the girl’s village. The girl meets them, standing at the entrance of the principal house, dressed in the new clothes sent on behalf of the bridegroom, and holding out her cloth for the reception of presents. The boy’s father goes up to her and smooths her hair with his hand, chucks her under the chin with his right hand, and makes a noise with his lips as if he were kissing her. He then touches her feet, places a rupee on the skirt of her cloth, and retires. The other members of his party follow his example, giving small presents of copper, and afterwards the women of the girl’s party treat the bridegroom in the same manner, but they actually kiss him (chūmna). Betrothals can be held only in the five months from Māgh (January) to Jeth (May), while marriages may be celebrated during the eight dry months. The auspicious date is selected by the Joshi or caste-priest, who is chosen by the community for his personal qualities. If the names of the couple do not point to an auspicious union the bridegroom’s name may be changed either temporarily or permanently. The Joshi takes two pieces of cloth, which should be torn from the scarf of the boy’s father, and ties up in each of them some rice, areca nuts, turmeric and dūb grass (Cynodon dactylon). One of these is marked with red lead, and is intended for the bride, and the other, which is left plain, is for the bridegroom. At the wedding some of this rice with pulse is placed with a twig of mahua in a hole in the marriage-shed and addressed: ‘You are the goddess Lachhmi; you have come to assist in the marriage.’

The Halbas, like the other lower castes of Chhattīsgarh, have two forms of wedding, known as the ‘Small’ and ‘Large,’ the former being held at the bridegroom’s house with curtailed ceremonies, and being much cheaper than the latter or Hindu marriage proper, which is held at the bride’s house. The ‘small’ wedding is more popular among the Halbas, and for this the bride, accompanied by some of her girl and boy friends, arrives at the bridegroom’s village in the evening, her parents following her only on the third day. On entering the lands of the village her party begin singing obscene songs filled with abuse of the bridegroom’s parents and relatives. Nobody goes to receive or welcome them, and on reaching the bridegroom’s house they enter it without ceremony and sit down in the room where the family gods are kept. All this time they continue singing, and the musicians keep up a deafening din in accompaniment. Subsequently the bride’s party are shown to their lodging, known as the Dulhi-kuria or bride’s apartments, and here the bridegroom’s father visits her and washes her big toes first with milk and then with water. The practice of washing the feet of guests, which strikes strangely on our minds when we meet it in Scripture, was obviously a welcome attention when travellers went bare-footed, or at most wore sandals, and arrived at their journey’s end with the feet soiled and bruised by the rigours of the way. Another of the bridegroom’s friends pretends to act as a barber, and shaves all the bride’s men friends with a piece of straw as if it were a razor. For the marriage ceremony proper the bride and bridegroom stand facing each other by the marriage hut with a sheet held between them; the Joshi or caste-priest takes two lamps and mingles their flames, and the cloth between the couple being pulled down the bridegroom drags the bride over to him. If the wedding is held on a Sunday, Tuesday or Saturday the bridegroom stands facing the east, and if on a Monday, Thursday or Friday, to the north. After this the cloths of the couple are tied together, or the end of the bridegroom’s scarf is tucked in the bride’s waistcloth, and they go round the marriage-post seven times, the bride following the bridegroom throughout. A plough-yoke is then brought and placed close by the marriage-post and the couple take their seats on it, the bride sitting on the left of the bridegroom. The bundles of rice consecrated by the Joshi are given to them and they throw it over each other. The bridegroom takes some red lead and smears the bride’s face with it, making a line from the end of her nose up across her forehead and along the parting of her hair. He says her name aloud and covers her head with her cloth. This signifies that she is a married woman, as in Chhattīsgarh unmarried girls go about with the head bare. After this the mother and father of the bride come and wash the feet of the couple with milk and water. This ceremony is known as Dharam Tīka, and after its completion the bride’s parents will take food in the bridegroom’s house, which they abstain from doing from the date of the betrothal up to this washing of the feet. It is on this account that they do not accompany the bride but only follow her on the third day, but the reason for the rule is by no means clear. On the following day more ceremonies are performed, and the friends of the couple touch their foreheads with rice and make presents to them of cowries. Last of all the bride’s parents come and give them cattle and other articles according to their means. These gifts are known as Tikāwan and remain the separate property of the bride which she can dispose of as she pleases. The ceremonies usually extend over four days, the wedding itself taking place on the third. The bride’s party then go home, leaving her with her husband, and after a week or so they return and take the couple to the bride’s house for the ceremony known as Pinar Dhawai or getting their yellow wedding clothes washed. The bridegroom stays here two or three weeks, and during this time he must work at building or repairing the walls of his father-in-law’s house. The custom of serving for a wife still obtains among the Halbas, and the above rule may perhaps indicate that it was once more general. At the end of the bridegroom’s visit his father-in-law gives him a new cloth and pair of shoes and sends him back to his parents’ house with his wife. The expenses of the wedding average about fifty rupees for the bridegroom’s family and from five to thirty rupees for the bride’s family.