полная версия

полная версияA Book of Nimble Beasts

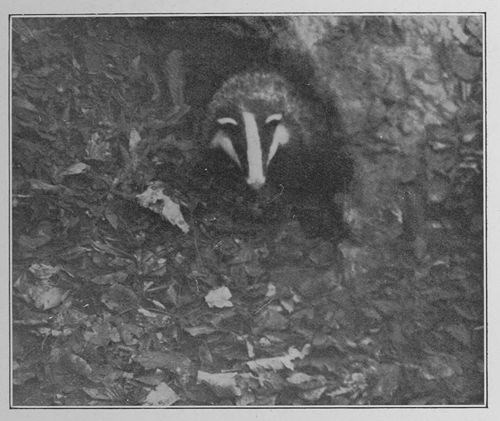

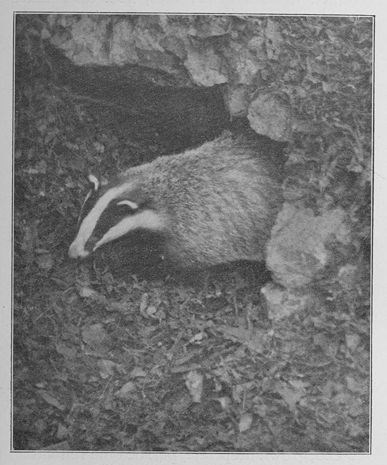

Viewed from below—it opened near the skyline—the hole seemed promising enough. It was a spacious sheltered hole, almost a cavern—the depths of it ink-black, the entrance to it jagged and arching. The Fox Cub stole up cautiously and stopped dead on its threshold. Something was in possession, something which split the darkened void in three; something which crept out slowly from the black, first shadowy grey, then white—a clean-cut fleur-de-lys of white.

It was another Badger.

The Fox Cub leapt back sideways, but even so she caught him. She came out (thirty pounds of her) full charge, and caught him low. The attacking badger tosses like a bull, trusting to weight and side-swing of the shoulders. He somersaulted twice. The Badger held straight on her course and disappeared downhill.

The Fox Cub slowly pulled himself together. Had he been bitten? Bruised he was all over, and sick, and giddy; and so, the hole being there, he crept within it, and crawled down the main shaft for fifteen yards, and took one of four turnings, and followed this until it forked, and then chose the right gallery, and so attained the nest. Rather the haystack, for the making of it had almost stripped an acre. Bracken there was, and bent-grass, thyme and clover, arum stalk and bluebell, thick swathes of them inextricably tangled, bedding enough for twenty half-grown cubs.

There was food also. He found a rabbit's leg at once, then a stiff mummied frog, then half a snake. He made a closer search, and found more rabbit. Each find he sampled. Most of them he gulped, but some he buried carefully for seasoning, scraping small hollows to receive them, and plastering earth upon them with his nose. This done, he coiled himself up tight, and for five minutes dozed with wakeful ears. Thirst brought him to his feet again; thirst and a sense of danger. Clearly this was the Badger's hole—he owed that Marten something. The hole had a main entrance. From this a single shaft led fifteen yards, but then it split, and smaller tunnels joined it, tunnels which might end blind. Badgers no doubt were most benevolent, but Badgers seem to charge at sight, and tunnels were poor places to be charged in. The last reflection scared him back to sense. He would be cornered hopelessly, would not know which of twenty turns to take. That settled it. To wait for them was madness. He must go.

It was another Badger

He reached the entrance without accident, and dropped soft-footed down the slope. A puddle on the ride was in his mind—a puddle just beyond the Polecat's stump. He reached this safely also, stooped down his head, and lapped his fill.

The wood was oddly silent. Dark clouds had massed low in the sky and streamed to either side, outflanking it. Beneath their dreary shadow the green and russet of the trees faded to lifeless grey. The grass-blades stood up stiffly; the leaves hung stiffly downwards. All that was weatherwise was taking cover. Down from the summit of the ride came the two Badgers, bumping. They travelled leisurely.

First He would root an arum up (a flick with one fore-paw), and She would place her paw where his had been. Then He would stretch tiptoe against an oak, and She would do the same. Then He would wheel sharp right or left, and She would follow like a truck.

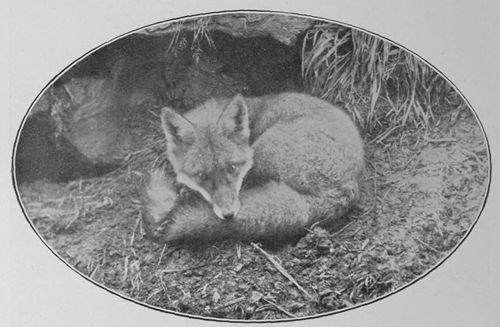

SHE CAME OUT FULL CHARGE

The Cub had time to entrench himself securely. He chose the summit of the Polecat's stump, and from it watched the pair of them bump past. They quickened as they faced the rise, and grunted to each other; then, with their heads down, sped in line uphill.

And with their going came the rain.

It spattered in large warning drops, then swished in sheets. Even before the thunder-peals, and rattle of fierce hail, the stump became untenable. The Fox Cub scrambled down from it, headed a dozen different ways, and, in the end, grown desperate, pursued the retreating Badgers. He caught them as they reached the hole, and saw them topple down it. He gave them half a minute's grace and toppled after.

And in due course of Time, His Wife

What happened next? That I can only guess at. Perhaps there was a Fox Cub course for dinner; perhaps (and this, I think, is likeliest) the Badgers took small notice of his entry. They may have even welcomed him, and, in due course of time, his wife.

SHEEP IN WOLVES' CLOTHING AND WOLVES IN SHEEP'S CLOTHING

(SEPTEMBER)

The Lobster Moth

Caterpillar

Pretending to be a Spider

THE wolves and sheep I am going to talk about are all of them insects, or rather all of them but one, for scientific people do not allow us to call spiders insects. Insects have six legs and six legs only, while spiders and mites and those sort of people have eight, and there are a great many other differences between spiders and true insects which would make it quite a dreadful blunder to put them in the same case in the Museum, or to speak of them in the same breath when you know you are talking to clever people.

The Spider, as you might guess, is one of the Wolves, and so is the Dragon in the Water-weed, who turns into one of our largest dragon flies, if he is lucky; while the caterpillars and the Giant Wood Wasp are just silly harmless sheep.

Have you ever thought of the wonderful struggles which are always going on in the insect world—the struggles to eat, and the struggles not to be eaten? Nearly all insects seem to be the food for something or other. Most animals enjoy them thoroughly, so do many birds, and many reptiles and amphibians (frogs and toads) and many fish. I think that spiders live on them entirely, and they have also cannibals to fear among their own kind, for though most insects feed on plant-juice, quite a large number of them turn to stronger meat, and spend their lives in hunting their poor relations. It sounds rather horrible, doesn't it? But we may be quite sure that everything of the kind has been mercifully arranged so that this beautiful world of ours, with all its joy and colour, and its millions and millions of happy children—I do not think that any lives but those of human beings are ever really unhappy—may keep its beauty always. That is why the ichneumon flies have to kill down the caterpillars, for, if there were too many caterpillars, there would be no hedgerows, let alone vegetables for dinner; and the Rove Beetles, who have curly cock-up tails, have to kill down the little boring beetles, for, if there were too many little boring beetles there would be no trees; and the Crabros have to kill down the blue-bottles, for if there were too many blue-bottles—well, goodness knows what would happen to some excitable people.

We must believe then that things are best as they are—that a struggle for life is part of a Great Plan, Greater than our human minds can grasp, and that the lives of the hunters are as useful in their way as the lives of the hunted.

Now how would we ourselves act, if our lives depended on catching things? And how would we act if our lives depended on not being caught? I don't think we could add much to what the insects and spiders have taught us. To hunt successfully you must get so near to your quarry that you can kill it. If you are quicker-footed, well and good. If you are slower-footed you may employ something quicker-footed than yourself—this is what happens in fox-hunting; or you may approach without being seen—this is what happens in deer-stalking: or you may hide yourself and wait for your quarry to approach you—this is what happens in tiger-shooting; or, lastly, you may employ traps and snares, which is how most fishing is done. I don't think that any creatures but ourselves employ lower creatures to hunt for them, but the other ways are used by all sorts of animals, and the last two are used more skilfully by insects and spiders than by anything else.

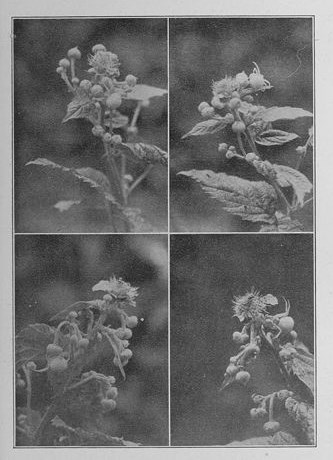

THE SPIDER ON THE BRAMBLE BLOSSOM

Look at the pictures of the spider on the bramble-blossom. This particular spider belongs to a family called Thomisus (I don't know why) and he varies in colour from a bright sulphur yellow to a delicate green, which is an exact match to the green of an unopened bramble-bud. In three of the pictures (a fly has settled close to the spider in two of them) you will be able to make out the spider pretty soon, I expect, for he has stretched his legs out. He keeps quite still in this position, and I think he fancies that he is a bramble-bud. But in the other picture I am pretty sure that, if he did not happen to be a rather fat spider, you would find it very difficult to distinguish him, and you may be certain that a fly would find it just as difficult. He is a wolf in sheep's clothing, and the sheep are bramble-buds.

The Dragon in the Water-weed

The Dragon in the Water-weed

This is the back of him, and you can see that he is covered with a delicate water-weed

And now for the Dragon in the Water-weed. You will not be able to make him out at all at first, but if you look long enough you will see his body which is too thick to be a piece of weed, and if you then let your eyes travel upwards, you will see his "mask," which is like a pair of folding-doors. These open and let his jaws out when he wants to use them. And his disguise is even more slim than that of the spider, for not only does he mimic the Water-weed round him—his straggly legs, which you should be able to make out also, help him in this—but he actually becomes part of his surroundings, for all over him grows a delicate water-weed, and when he is at the bottom of the pond, where he spends most of his time, he is part of the bottom of the pond, and the creatures which he would eat walk past him carelessly. He is a wolf in sheep's clothing, and the sheep are water-weeds.

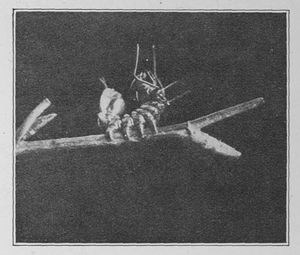

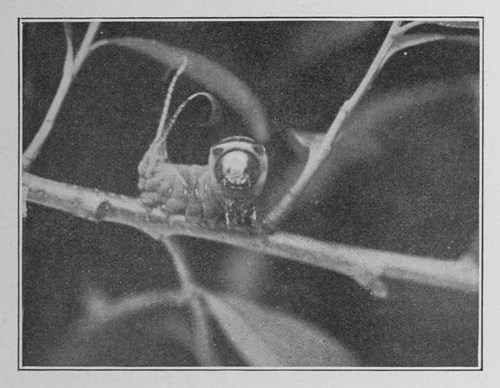

The Lobster Moth Caterpillar

As he looks when angry

And now for the sheep who are just as clever really as the wolves. Two of these are caterpillars—quite the most curious pair of caterpillars to be met with in this country—and the third is a sawfly. Sawflies get their name from having an instrument with which they can bore or saw, as the case may be, into leaves or trees, and this is the largest one we have in England.

The hunter-insects, as we have seen, disguise themselves so as to get near their victims unawares, and the hunted disguise themselves very often in the same way so as to avoid being seen, but sometimes in such a way that if they are seen they may appear to be much more terrible creatures than they really are. And so we have the sheep in wolves' clothing.

The hunters of the caterpillars are the ichneumon flies. Ichneumon flies do not eat caterpillars but lay their eggs inside them. They have a special instrument for the purpose, and when the grubs hatch out they gradually eat away the fleshy parts of the caterpillar so that it seldom has strength enough to turn into a chrysalis, let alone a butterfly, or moth, or beetle, as the case may be. Now what is the chief enemy of a fly? Why, of course, a spider. If then something which dreads an ichneumon fly can make itself look like that fly's worst enemy, a spider, it will have a good chance of scoring off the fly.

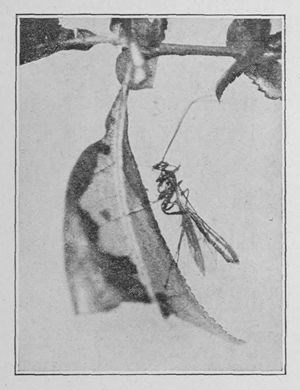

The Ichneumon Fly

The Caterpillar of the Lobster Moth, of which I show you two pictures, can do this to a nicety. He has, as you see, an extraordinary shape for a caterpillar, I don't think that any other caterpillar in this country has the same long skinny legs—and he is able to strike extraordinary attitudes which make him look very spidery indeed, particularly from in front, for then the two little spikes at the end of his lobster body appear over the top of his head and look like a spider's pincers. Mother Nature has been very careful of her Lobster Moth caterpillar. When he is quite a baby he looks just like a little black ant. When he is asleep he folds up his legs and looks like a shrivelled beech-leaf—he usually feeds on beech—and, when he is attacked by an ichneumon fly (you can make him think he is being attacked by tickling him with a paint-brush) he turns himself at once into a sham spider, by throwing back his head as far as it will go and shuddering his skinny legs in the air.

The Puss Moth Caterpillar

As he looks when angry

The Puss Moth caterpillar is almost as curious. He, too, strikes fearsome attitudes. He has eye-markings to help him (you will have read about these elsewhere) and he can also squirt out an acid from underneath his chin. These two defences are probably most useful against animals and birds and lizards and creatures of that kind, but they do not seem to be much use against an ichneumon fly, and so Mother Nature has helped him further, by giving him two little pink whiplashes, which shoot out from the prongs at his tail end when he is really annoyed. When a fly comes near him he brandishes them as you see in the picture.

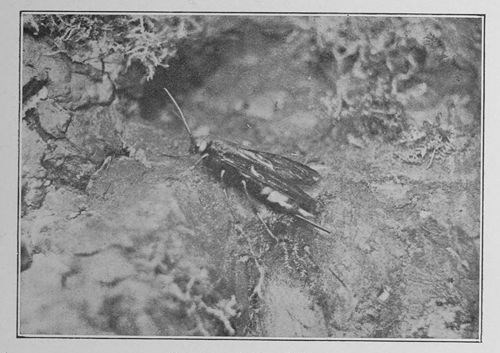

The Giant Wood Wasp

It has no poisonous sting, though it looks as if it had a very fine one

Our last sheep is the Giant Wood Wasp, who is not a wasp at all, and is much more common in this country than he used to be. He is a handsome black and yellow insect with a body about an inch long, and his wolf's clothing is his black and yellow colour. This is the commonest wolf's clothing of all. You know I expect that a number of stinging insects, wasps and bees, have a black and yellow, or black and red colouring, and you know too, I dare say, that there are a great many flies who have no stings but are coloured in much the same way. Well, it is thought that these flies without stings, of which the Giant Wood Wasp is one, may sometimes avoid attack because they frighten their enemies by looking as if they had stings. Suppose a young sparrow ate a wasp, he would probably get stung, and it might happen that next time he saw a black and yellow fly, he would mistake it for a wasp and so not eat it. If this did happen, the fly would have owed his life to being black and yellow.

THE BEASTIES' BEDTIME

(OCTOBER)

The Queen Wasp in her winter sleep

She puts her wings underneath her body, so that they sha'n't get damaged, and holds on chiefly with her mouth

HOW would you like to sleep straightaway through the winter, and miss Guy Fawkes, and Christmas, and New Year, and Valentine's Day, and skating, and snowballing, and round games in the evening, and having stories read to you by the fire, and all those delightful things which come to cheer us when the weather is damp and gloomy, making us feel somehow that summer is a queer, impossible kind of time, just as in summer we find it hard to imagine what it feels like to be really cold? I want you to remember in this winter which is coming what a number of little creatures in the wide world around you are fast, fast asleep. I want you to think how wonderful it is that these little creatures are able to dream away the time when there is nothing for them to eat, and to wake again when there is food in plenty.

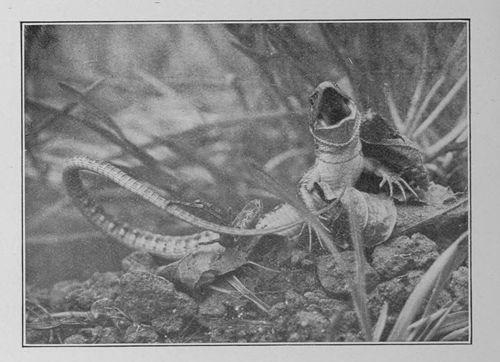

Bill the Lizard

Every year when the evenings begin to come quicker and quicker, and grow colder and colder, Mother Nature, who is the mother of our dear own mothers, puts her babies to bed at the time which she knows is best. A queer set of babies they are! Babies of such different kinds that it is a wonder she can keep them all in her head, and not have to say sometimes to herself: "Good gracious, I forgot my dormouse: and I don't believe my brown lizard was properly tucked up in the grass-tuft; and as for my prickly hedge-pig, I don't remember where I sent him last."

But Mother Nature never does forget, and never spoils her babies. She whispers "bedtime," and they go.

The little insects go first—the flies, and beetles, and earwigs, and frog-hoppers, and myriads of other tiny creatures which you can see in the grass on any warm day by just lying down and opening your eyes.

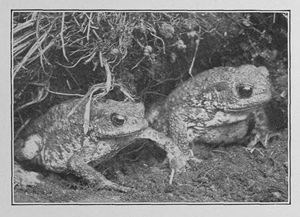

Toadums

For all Mother Nature's care I fear that most of these die, but some may manage to live through the cold, and among the larger kinds of insects some always do. You remember what I told you about the Brimstone Butterfly! The Queen Wasp is another of the lucky ones.

She creeps into some sheltered crevice, where she can find a shred of something small enough to take into her mouth. This sounds queer, doesn't it? I will tell you the reason. The Queen Wasp sleeps hanging by her jaws, and hardly trusting to her legs at all. You can see what she looks like in the picture, and you must notice that she has tucked her wings right underneath her body so that nothing can brush against them.

After the insects go the reptiles and the frogs. These are cold-blooded creatures, so they have no need to make a nest to keep them warm, but they don't like to be too cold, and always creep somewhere where the frost will not reach them. Bill the lizard sometimes goes deep down into a large grass-tuft, and sometimes creeps into a mouse-hole. Froggin dives into a pond and wriggles into the mud, or underneath a stone, and there sleeps under the water until the hot sunshine comes again, and he knows, by the feel of things, that it is time to be moving. Toadums prefers to sleep on land. He lies quite flat, with his hands in front of his eyes, and wakes up a little later than Froggin.

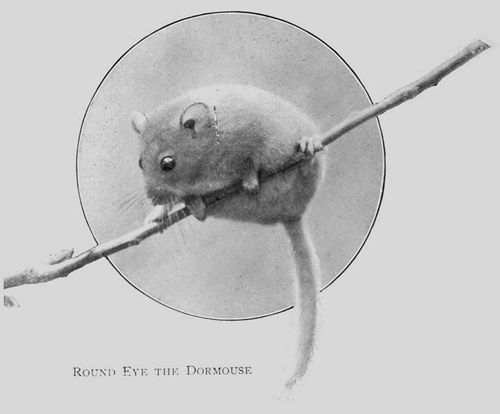

The Dormouse in his winter Sleep

He bunches himself up so as to close all the doors that the air can get in by, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, everything

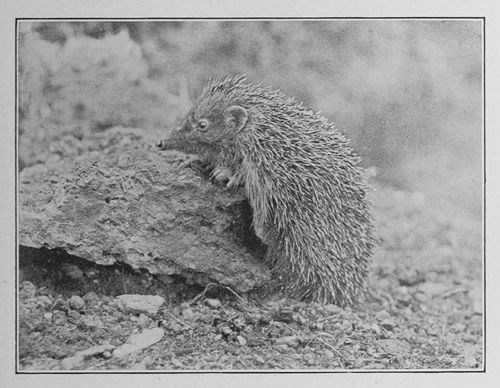

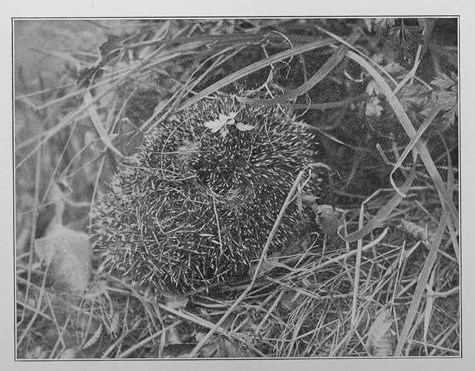

After these the animals. Round Eye the dormouse goes to sleep about November. He builds a nest of leaves and grass all around himself, and, if the winter is cold, sleeps straight away into April. If the winter is warm, however, he may wake up and eat a little food, and if he is a wise little mouse, as he usually is, he keeps a little store of nuts and seeds at hand in case he does wake up. Prickles the hedge-pig does much the same. He has a nest which is even warmer, for, besides the leaves and grass which make the round of it, he rolls his spines into anything soft which will stick to them and so has a nice warm blanket next to his skin. Once he has dropped off to sleep he stays asleep till the spring comes. I don't think he ever wakes up like the dormouse, or ever makes a store of food.

Prickles the Hedge-Pig

The only other animals which sleep the winter through in this country are the bats, and some of them sleep even longer than the dormouse and the hedge-pig; indeed, they are only awake for three or four months in the year. Sometimes there are crowds of them sleeping together in old caves, and tree trunks, and places like that, and it may be that they half wake up and talk to each other to pass away the time. Indeed, if you know their hole and can put your ear close to it, you can sometimes hear them talking and squabbling—faint little squabblings like the sound of a kettle simmering on the hob when you can just hear the tiny bubbles hitting each other and bursting with bad temper.

THE HEDGE-PIG IN HIS WINTER SLEEP

He is not so tightly coiled as when he shuts up to defend himself

When bats are flying about and hunting for moths they often squeak for joy, and then their voice is quite different. It is so high that some people cannot hear it at all; but you can make a noise just like it by striking two pennies sharply together, and if you can hear that being done when you are several yards away from the person who is doing it, you ought to be able to hear a bat squeak too.

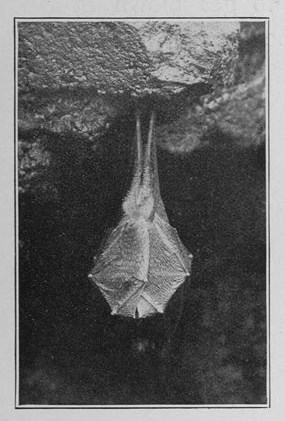

The Lesser Horseshoe Bat in his winter Sleep

He is hanging head-downwards and is completely shut up in his own wings, which, you see, are beautifully folded

You have to watch bats very closely before you can tell one kind from another, and I expect some of you will be surprised to hear that there are more different kinds of bats in England than there are of any other kinds of animals. There are, at least, twelve different kinds of English bats, and, as bats now and then seem to get blown over the sea from France, or be brought in the rigging of ships, quite a strange foreign bat may turn up sometimes.

THE BLUNDERS OF BARTIMÆUS

(MICHAELMAS DAY)

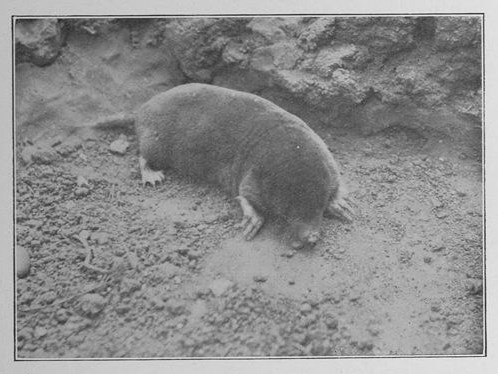

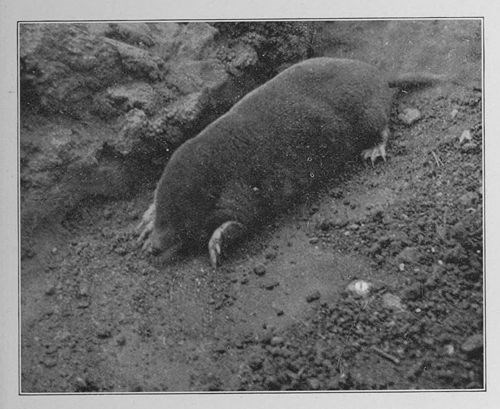

Bartimæus

BARTIMÆUS was simply mole-tired (which is as tired as a beastie can be), and he lay on his side, with his nose tucked into his waistcoat, and dreamed of Nydia, fretfully. Nydia was half a field away, dozing in a snug fortress of her own, with four fat helpless babies to attend to, and not a passing thought for Bartimæus.

Five times within twelve hours had Bartimæus sought her. Five times had he traversed his main-line tunnel, turned eastward at the junction by the fence, and, breasting up the up-grade full tilt, thrust an inquiring nose at Nydia's nest. Why shouldn't he? Why should he stand on ceremony with four fat, squirmy, wrinkled, hairless infants?

But Nydia had been mightily offended. Each time she had boxed his ears. Each time she had bitten him. And so he had retreated; not for fear, but for black shame—black shame which he had brought upon himself; for Father Moles may not approach Mole babies—that is Mole law, and that has been Mole law since Moles first dug.

Long journeyings these to Nydia, a hundred yards each way at least, but not of length to tire him. He had found time and energy for in-between excursions. One to the mill-house orchard—there staring hillocks proved it; one to the sacred croquet lawn—he left his marks here also; one to the mid-field partridge nest, which meant one egg the less.

He headed straight for Water

A cheerful strenuous day's work; on which, but for the finish of it, he might have slept at ease.

Nydia's last bite and buffet had been real.

She swept her right hand cross-ways, baring her teeth in line with it, and screwing round her shoulders for the swing. Then she lunged backwards viciously. This meant a dragging wound which hurt, and Bartimæus had bitten too, and, as ill-luck would have it, bitten a baby. Nydia flung at him squealing, and, when a Mother Mole flings at you squealing, one prudent course and only one is open.