полная версия

полная версияA Book of Nimble Beasts

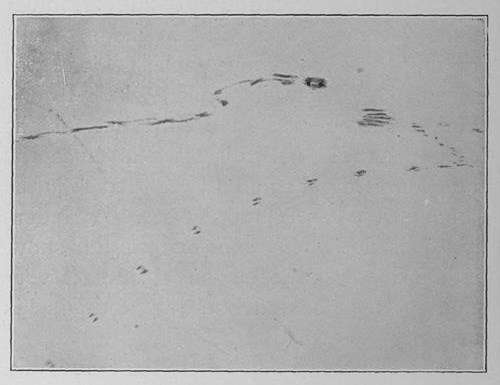

The Weasel's Trail

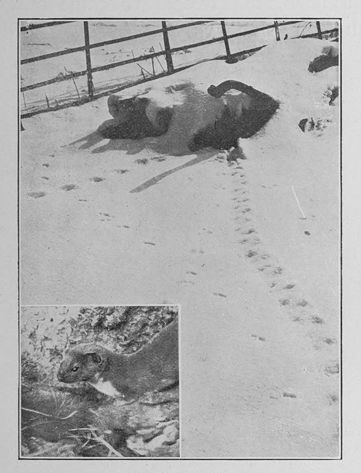

We will begin with the Weasel's trail in the picture on the opposite page. You will see that there are two different looking trails showing, but they both belong to the same weasel. The reason they look so different is that one set are fresh and the other set are a day old. There has been a slight thaw, and this has melted the snow so that the oldest trail has fallen in a little. All the trails lead to a woodpile, and I used, after the snow had all gone, to go to that woodpile in the evening and wait for the weasel to come out, and watch him play, which he always did for some time before he started hunting.

Where the Weasel met the Mice

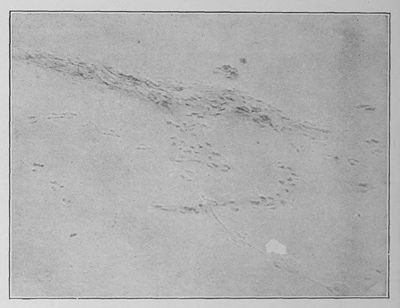

The mice had made quite a beaten track from one hole to another—this you can see at the top of the picture. The other tracks are the weasel's, except one, which shows the imprint of a mouse-tail

It was quite exciting to follow that little Weasel's trail in the snow. I came to where he had startled a moor-hen and to where he had startled a rook, and to where he had had a splendid game chasing mice. I am showing you a picture of this, and you will notice at once the line down the centre of one of the tracks, which is made by Mousey's tail. Another of the pictures shows you two mouse-tracks running to separate mouse-holes, which I was very glad to know about, and which I don't think I should ever have seen but for the tell-tale snow. A Rat's track is much the same, only larger; and a Stoat's track is the same as a Weasel's, only larger. A Hedgehog does not often come out in the snow, but he does sometimes and leaves a very smudgy track behind him, for he drags his fur along the ground.

Where The Weasel met the Rook

You can see where the Rook's wing hit the snow

Two Mouse Trails leading to holes in the snow

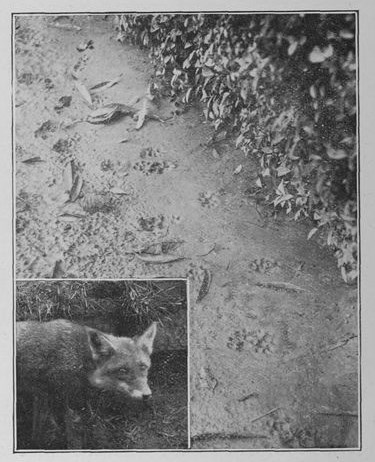

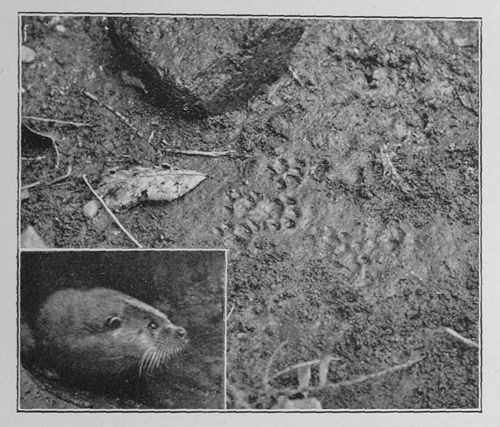

Snow shows one much more than mud, but, unless it is of just the right softness the prints in it are apt to be splodgy, and I don't think you ever get so perfect a track in snow as you sometimes do in mud. The pictures of the Vixen's and the Otter's footprints will show you what I mean. A Vixen's footprints are smaller than a Fox's, and a Fox's footprints are smaller than most people think, indeed a Fox is a smaller animal than most people think. I have a little wire-haired terrier whose footprints are much larger than those of a Vixen. At the same time it is not very easy to distinguish a Fox's track from that of a small dog. Generally a Dog's claws make their mark as well as the pads, and this does not often happen with the Fox; but I think a better way of telling the difference is to remember that a Fox's pads are more oval-shaped than a Dog's. You will always, I think, be able to tell an Otter's footprints (some people call them the Otter's seal) by their size, and by their leading to or from the water. Usually the claws can be clearly traced and sometimes the webbing of the feet as well. I have never seen clean-cut Badger's footprints—all I have met with have been very broad and splodgy, more smears than patterns—and I have never seen a Marten's trail at all.

The Fox's Footprints

Footprints tell us a good deal of what is going on about us, and so do "runs" in the grass, and "runs" in the hedges. But, of course, there are other things to be looked for. Often one finds the remains of beasties' meals, nuts for instance. Nuts with clean-cut round holes in them have been gnawed by Dormice, nuts with jagged holes by Red Meadow Mice and Wood Mice, nuts split clean in half most likely by Squirrels. Otters leave half-eaten fish about sometimes, and scattered broken eggshells tell you where Stoats have been running the hedgerow. If you notice where you find these things and keep your eyes open, you are sure in time to see what you are looking for.

And the last thing that Winnie remembers was the Great Green Grasshopper's Wife hurrying the little Skipjacks off to bed.

THE GREAT GREEN GRASSHOPPER'S BAND

(CHRISTMAS DAY)

"I BEG your pardon!" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife.

"I think I ought to beg yours," said Winnie politely.

Perhaps, however, you would like me to begin at the very beginning. Very well, then; but you must remember that, for most of it, I can only tell you what Winnie told me. It all seems to have happened between Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. On Christmas Eve, our Cricket, who lives in the kitchen behind the hot-water pipes, had started chirruping as usual, and I had gone into the library, and hunted out an old, old Christmas book and started reading to my small friends a story which began with a cricket singing against a tea-kettle. Then we had had a snapdragon, and then the waits had come round, so everything had been as Christmassy as ever it could be. Just as the waits finished Winnie had got into bed and snuggled herself up. All this I can vouch for myself, for I was there all the time, and I can remember how good the snapdragon was, though I did not eat quite so many raisins as one little girl. However, as she said afterwards, "Even if I did eat thirty, Father, it was quite worth it."

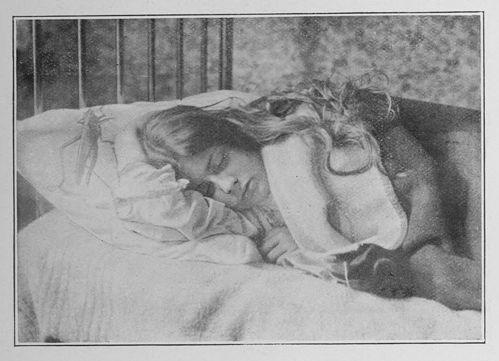

So much for the true part of the tale—now for the magic. Winnie tells me that she never went to sleep at all! The waits and the cricket and the snapdragon and the kettle were all mixed up in her head, and the snapdragon had turned hungry and was trying to snap up the waits, and the kettle was puffing like a little traction engine, and in between the puffs there was a sad little chirrupy sound which she thought must be the cricket. It seemed only kind then that she should slip out of bed, listen on the landing, and creep down to the kitchen to see how the cricket was getting on. She found him sitting on the hearthstone and watching the people in the fire going to church.

Winnie tells me that She never went to sleep at All!

"I can't attend to you now," he said, "I'm just going out."

Winnie had half expected him to speak, but she was a little frightened all the same, and a little curious too.

"Do take me with you," she said. "Where are you going?"

"Where am I going?" said the Cricket in a surprised tone. "Why, it's Christmas Eve!"

"Yes, isn't it lovely!" said Winnie; "and to-morrow there'll be presents. But where are you going?"

"I'm going to be a wait, of course," said the Cricket. "I've been practising all the evening. Listen!"

He ducked his head and lifted up his wings, and a chirrup fluttered out of them and ran all round the dresser. It was a chirrup! It wriggled in between the plates and dived into the soup-tureen, and climbed the tea-cup handles, and danced upon the saucers, until the sour deal boards, which had had all the softness scrubbed out of them (and were cross-grained to begin with), felt little thrills of pleasure running down their backs. Then it climbed up the wall and rattled the dish-covers, and at last it died away with a little squeak inside the coffee-pot.

"What do you think of that?" said the Cricket triumphantly.

"It's beautiful," said Winnie; "but where are you going?"

"You'll see presently," said the Cricket; "and I wish you wouldn't chatter so. You nearly made me forget him."

The Cricket was sitting on the Hearthstone watching the People in the Fire going to Church

"Forget who?" said Winnie.

"Our drummer," said the Cricket. "Keep still—I heard him a minute ago."

There was a long pause—so long that Winnie almost screamed, for there was nothing but the clock-tick to listen to.

Then something joined the clock-tick—One-two-three-four, pit-tip, tip-pit, one-two-three-four, pat-tap, tap-pat (just like soldiers a long way off, as Winnie explained), and presently the drummer himself appeared. He was a very small, squat, round-shouldered beetle, and he came out of a hole in the beam which ran across the ceiling.

The Pair of Them dropped … on to the Edge of the Kitchen Table

"What a nuisance it all is!" he yawned. "I was just going off to sleep when I heard you. Is there no one else who can drum?"

"No one who can drum like you," said the Cricket, which is far the best way to answer these questions.

"Very well," said the Beetle, "but my wife must come too," and the pair of them dropped with two little flops on to the edge of the kitchen table. Then the clock chimed in—one-two-three-four, right away up to eleven.

"Shall I come too?" said a mean little oily voice from under the coal-scuttle. Winnie could just see the Cockroach's whiskers making quivery passes in the air, and she sat down and drew her nightie round her feet as tight as ever she could. She was quite relieved to hear the Cricket's answer.

"Of course not," he said; "you never played anything in your life."

"It's all the same to me," said the Cockroach. "I've given up those silly meadows long ago. Good-night, lunatics!" and he drew his whiskers in and disappeared.

"Was that eleven?" said the House Cricket, taking no notice of his rudeness. "We've no time to lose then. Come along!"

Winnie climbed up on his back as if it were the most natural thing in the world, and the two Beetles climbed up behind her. The drummer Beetle started playing at once—one-two-three-four, pit-tip, tip-pit; one-two-three-four, pat-tap, tap-pat—and the whole four of them sailed up the chimney. It was not hot (as Winnie explained), for the fire had burnt very low and that was what had beaten the kettle, but it was sooty, and she remembers quite well longing to see the clean, white snow on the roof. The Cricket went up crab-wise—a little jump to one side and a little jump to the other; so he took quite a long time to reach the chimney-pot, and when he crawled on to the edge of it the snow was all gone. ("That was the queerest thing of all, Father," said Winnie "there were leaves and flowers and sunshine, and it was just like summer.")

"Now hold tight," said the Cricket, "while I unpack my wings."

This was quite a long business, for the Cricket had to keep moistening his fingers, and Winnie and the Beetles had to keep crawling up and down his back, so as not to be in the way. At last everything was ready, and the Cricket poised himself on the edge of the chimney, spread his wings wide apart, and slid into the air. Winnie was just a little frightened at first, and she put her head down close to the Cricket's neck and shut her eyes and dug her fingers into the chinks of his back; but presently she felt that it was no good being frightened, for they were going quite smoothly, and the Cricket's wing-covers were high up on either side of her, so that she could hardly have fallen off if she had tried to. Soon she felt brave enough to raise her head very carefully and look about her. The kitchen chimney was some way behind, the great elm on her left, and the river close in front. Just before they reached the river the Cricket's wings buzzed like blue-bottles, and she felt they were going upwards. Then came another long, gentle glide, and the Cricket landed on the blackberry hedge at the bottom of the meadow.

"You must all get off here," he said.

Winnie stepped off his back on to a slippery thorn, missed her footing, and fell on the top of the Great Green Grasshopper's wife.

"I beg your pardon!" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife.

"I think I ought to beg yours," said Winnie politely—which is where the story began some time ago.

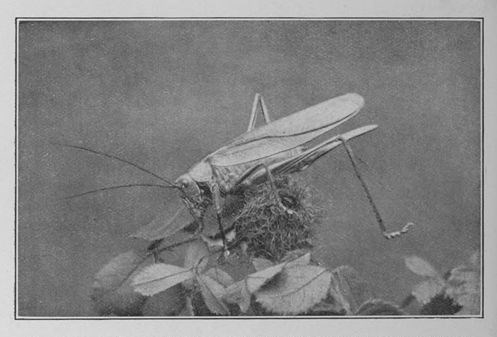

"I beg your Pardon," said the Great Green Grasshopper's Wife

The Great Green Grasshopper's wife was more amused than offended.

"Don't mention it," she said. "I suppose you've come to help us, and I'm very glad to see you. It is really most unfortunate, but I couldn't possibly let my husband come—the first Christmas Eve he has missed for years—but, as I said to him, 'If your leg's frostbitten, you're much better in your hole.' Don't you agree with me?"

"Oh, yes, I think so," said Winnie, who felt she must say something.

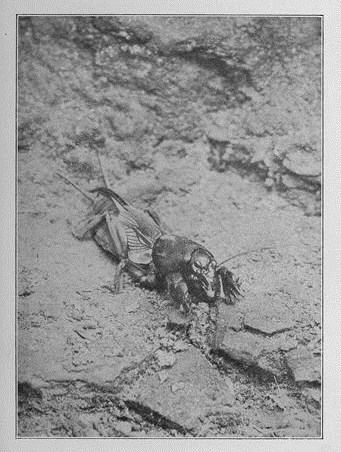

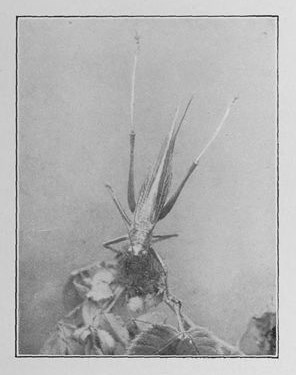

"Of course we shall miss him very much," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife, "but if the Field Cricket isn't too nervous, I dare say we shall pull through. I see you have brought our drummer with you, and here is the Mole Cricket coming up, and the Wood Cricket, and I saw the Bush-cheeps a moment ago. Do you really mean to tell me that you have never met any of them? Then I must introduce you. This is the Mole Cricket. You can't ever mistake him if you have once seen his feet; and this is the Field Cricket—you can't mistake a blackamoor like him either; and this is the Wood Cricket with the check trowsers; and the Bush-cheep always wears a brown tail-coat and a greeny waistcoat. Now you all know each other and we must get to work. What do you play?"

Winnie had been getting a little uneasy all this time, for the Crickets had been unpacking their instruments and making little scrapes just like the band before the pantomime, and she had felt that she would be expected to do something too, and had made up her mind as to what she would say if she were asked.

"I can play a grass-blade a little," she said.

"Well, there's lots of grass about," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "Let's hear you do it."

So Winnie picked a big blade of grass and jammed it tight between the balls of her thumbs and pressed her lips hard against it and began to play. The first note sent the Great Green Grasshopper's wife's hind legs straight up in the air, turned the Mole Cricket and the House Cricket and the Wood Cricket and the Bush-cheeps head-over-heels, and drove the Field Cricket into his hole.

"Easy, easy!" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "You nearly blew my tail off. Can't you play more softly?"

THIS IS THE MOLE CRICKET

"I'll try," said Winnie.

"Please do," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "There, I knew what would happen. See what you've done."

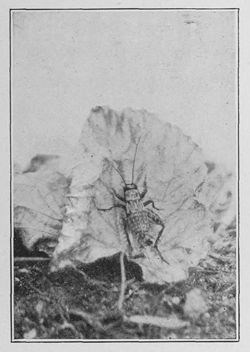

This is the Field Cricket

The Field Cricket had all but disappeared, and there were only two little black legs sticking out of his hole.

"It's no use your trying to play in there," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "Nobody will hear you at all."

"I can't help it," said the Field Cricket; "my nerves are completely upset."

"See what you've done," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife again. "It will take him twenty minutes to recover."

And she was quite right. For twenty long minutes they had to wait and look at one another, and even at the end of that time the Field Cricket still seemed very shaken.

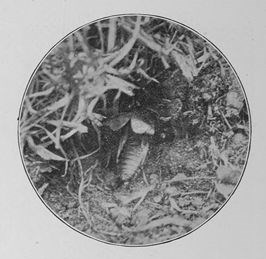

"I will do my best now," he said at last, "but I simply must have my head hidden." He had backed out of his hole a little way and lifted up his wing-covers. Every now and then he chirruped softly.

And this is the Wood Cricket

"Well, it's better than nothing," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife, "and you certainly have some excuse this time. Now let's begin." She climbed a little higher in the hedge, tapped sharply with one hind leg, and looked about her.

"Are you all ready?" she said. "Drums?"

"Here!" said the Beetles.

"First violin?"

"Here!" said the Field Cricket.

"Second violin?"

"Here!" said the House Cricket.

"Viola?"

"Here!" said the Wood Cricket.

"'Cello?"

"Here!" said the Mole Cricket.

"Flutes?"

"Here!" said the Bush-cheeps.

"Grass-blade?"

"Here!" said Winnie, screwing her lips up very tight.

"Good!" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife, and she reared herself up backwards and began to beat time with her hind legs.

"Two bars first," she said. "Now!"

At the third bar they all came in very fairly together, but before they had played half a minute the Great Green Grasshopper's wife stopped short.

("It was really worse than the real waits," Winnie explained. "It was like a million little glass stoppers being squeaked out of bottles—and they didn't seem to mind the time a bit.")

The Great Green Grasshopper's wife looked at Winnie quite severely.

"I asked you to play softly," she said; "you're drowning the whole band."

The First Note sent the Great Green Grasshopper's Wife's Hind Legs straight Up in the Air

"I can't play more softly than that," said Winnie.

"Well, there's only one thing to be done then," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "I must hunt up the Skipjacks."

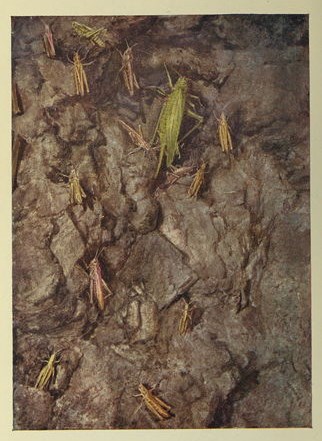

The Skipjacks are the little grasshoppers who live in the fields, and it takes quite a number of them to play a tune that you can hear.

He had Backed Out of His Hole a Little Way and Lifted up His Wing-covers

"Wait for me here," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife; "I sha'n't be long!" And she leapt like a jump-jim-crow and landed three yards clear of the hedge.

She really was some time away, but at last she reappeared driving the Skipjacks in front of her.

"It is so troublesome to keep them straight," she explained; "the little idiots! Look at them."

The Great Green Grasshopper's Wife Reared Herself up Backwards and began to beat Time with her Hind Legs

They certainly were a queer flock to manage, for they could only move by jumps, and when they jumped even they themselves had no idea of where they were jumping to. However, by driving them in front of her she managed to keep a few of them together, and at last she got them into their places.

"You must fiddle," she said, "as you never fiddled before. The band shall not be beaten by a grass-blade. Now altogether—one, two, three, four!"

It was really much better that time, and though Winnie could not pick up the tune, everybody else seemed quite pleased with themselves.

"That's better!" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "Now again!"

But before the words were out of her mouth the great hall clock chimed in, Ting—Ting—Ting—Ting——

"Midnight!" screamed the Great Green Grasshopper's wife. "What will become of us?"

Ting—Ting—Ting—Ting——

"It's fast!" cried Winnie: "I know it's fast. I put it on myself for getting up tomorrow."

"Are you quite sure?" said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife.

"Quite sure," declared Winnie; "it's five minutes fast at least."

"That's a great relief to my mind," said the Great Green Grasshopper's wife; "but, of course, we must stop at once."

Indeed, the Crickets were already packing up their instruments, and the last thing that Winnie remembers was the Great Green Grasshopper's wife hurrying the little Skipjacks off to bed.

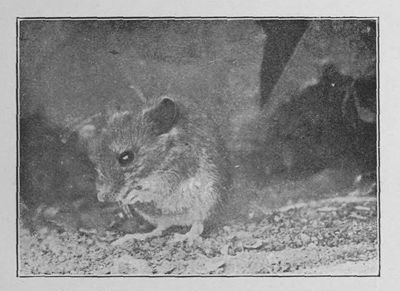

THE PYGMY SHREW

(BOXING-DAY)

FEW know him and the careless eye may never see him. He is so small,—that four of him just stop a mouse-hole; so light,—that ten of him just tilt an ounce. Yet, if you search the files, you find him eminent. The Pygmy Shrew in Cornwall! The Pygmy Shrew in Kent!! The Pygmy Shrew in Rutlandshire!!!

Thus fame is garlanded round mystery.

Man's kingdom is brick-built and parchment guarded. The beasties have a nobler heritage. Fence your broad acres as you please, yet they shall quietly share them, paying you naught, and taking what they will. Water and air and land are theirs by prior, nay primeval, right. So shall you bend before their quality, and, for their lineage, you shall respect them.

Something had brushed across the Pygmy's nose. He shook off three days' sleep in three half-seconds. Where was his tail? Sleeping, he swings it up across his face, and gathers all four feet within its shelter. His tail was there, but in its waking-place, behind him. Then something must have moved it. He stretched his neck and sniffed, long wheezy sniffs which ended in a shiver; then he peered down the shaft. He jerked back to avoid an avalanche—a blinding dust-cloud, a rattle of small stones, and, in the midst, two common shrews close locked.

But I go on too fast.

The stump is close against the rookery-fence. It is a stump of quality, a residential stump, a maze of winding roots and secret chambers, wherein field-folk may live without acquaintance. There is a fellow to it in the meadow, another fronts the rabbit mound, and all three hold like tenants.

The woodmouse first, round-eyed and debonair; then the bank-vole, he who is half a mouse, with chestnut coat, broad ear and estimable tail; lastly the ranny-noses; the common shrew—a velvet-coated pepper-tempered gallant; the Pygmy, who is common shrew refined—purple and orange ripple in his fur, and him my Lady Sunshine loves the best of all.

The Woodmouse First, Round-eyed and Debonair

All live together, yet apart, for, under ground, the stumps are intricate. The roots twist right and left and back upon themselves, and, over and beneath them, are the runs. Most are blind alleys, but a few creep on, and strike the upper air. The mice and voles reserve the lowest depths; they must be near the water; moreover they can tunnel where they will. The common shrews live higher, scratch two-inch levels where the rootlets aid them, and trust to their quick ears. The Pygmy takes what stouter beasties leave; and that is how the Pygmy's tail was moved—his sleeping-hole, the mould of some long-fallen stone, abutted on the shaft.

That two shrews should be fighting was quite usual. Shrews fight to keep their limbs in trim; they fight in play; they fight in deadly earnest. A veteran shrew is scarred in every part of him; great scars like thumbmarks, where new growth of fur has failed to draw up level with the old.

Yet even shrews need open ground to fight on. The Pygmy waited till the dust had cleared, then peered into the darkness. The scuffling of them could be plainly heard; and, sharp above it, rose their vicious war scream. The Pygmy knew what that meant—a bolt for upper air and honest fighting. He crouched back prudently. They rattled past once more in quick succession, the foremost gibbering his distress, the hindmost dumb. But this was dubious measure of their quality, for, where there is bare tunnel-room for one, one needs must be in front, and, then, his only weapon is his voice.