полная версия

полная версияA Book of Nimble Beasts

SPINIPES THE SAND-WASP

(MIDSUMMER DAY)

AUTHOR'S NOTE

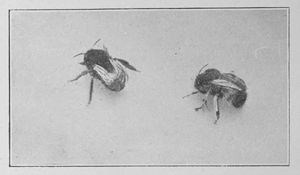

THIS insect-tale is based on observations of fact extending over several summers. It may interest some of my readers to know the scientific names of the chief characters mentioned. I do not think that any of them have popular names. The heroine is the solitary Sand-Wasp Odynerus Spinipes, a blacker and somewhat smaller insect than the familiar yellow Wasps of Town and Garden. The Red King and the Black Queen are the male and female of a solitary Bumble Bee, Anthophora Pilipes. The Mistress of the Robes is a "Cuckoo" Bee, Melecta armata, which attends on Anthophora, and lays its eggs in the cells made by Anthophora for her own eggs. The grubs of both feed on the honey and pollen which Anthophora alone has the trouble of procuring. O. Spinipes has several cuckoos, the most officious being the jewel flies, Chrysis ignita and Chrysis bidentata, whose grubs, I fancy, eat the grub of Spinipes, as well as the food stored up for it. The Ophion is a common Ichneumon fly, and the beetle-grubs belong to a very common and destructive weevil, Hypera variabilis.

THE Sand Cliff splits the old gravel-pit in two, and, jutting southward, fronts the mid-day sun. The cuttings driven east and west of it have long been clothed with furze and briar and nettle. Rank grass conceals the cart-track round its base, and, on its summit, a thin, root-bound soil gives foothold to a straggling hedge of privet.

THE SAND CLIFF SPLITS THE OLD GRAVEL-PIT IN TWO

Man, needing gravel only, scorned the sand; and, as he turned his back on it, came Nature, gently mothering; and brought it warmth, and light, and life.

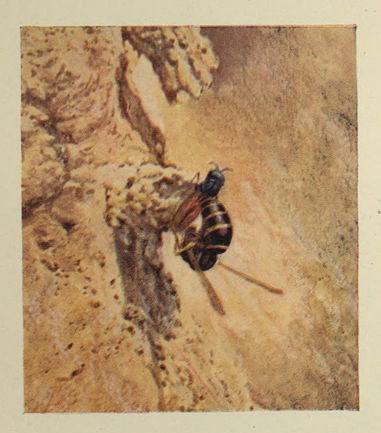

First the Wild Bees, Red Kings, Black Queens

First the wild Bees, Red Kings, Black Queens, fringe-footed, shaggy-coated. These made a chambered palace of the cliff, and peopled it within a summer. With them came Lords-in-Waiting and their Ladies, in liveries of black velvet, ermine-faced; and, after these, a fluttering gauze-winged host—jewel-flies ablaze with green and blue and crimson, trim slender-waisted digger-wasps, long-streamered swart ichneumons. And, last of all, came Spinipes herself.

Straight from the blue she dropped on May's last morning, swerved through the hum and racket of the Bees, poised with her smoke-grey wings a-whir, and lighted softly on the centre ledge, her ebony body mirroring the sun, her five gold girdles blazing.

Down dropped a Red King at her side. He stared at her right royally, and kept right royal silence, yet there was kindness in his yellow face, and kindness in the purr of his departure.

Down dropped a Black Queen in his place, and danced and hummed about her, and measured her slim-waistedness, and buzzed her disapproval.—"What is it?" asked she snappishly. "Why does it come in this get-up? Where has it left its furs?"

Down dropped a Red King at her side. He stared at her right royally

"It never had furs," said a voice behind her. It was her Mistress of the Robes.

"I know the family, Ma'am. Queer clothes, of course. But artists, Ma'am, artists to the toe-tips."

"Artists in what?" said the Black Queen.

"In Sand, Ma'am, in Sand. See, she's starting now."

"That's hive-bee's work," said the Black Queen contemptuously.

"The art comes at the finish, Ma'am–"

"Well, call me when it comes," said the Black Queen, "and keep her off the nurseries, and clean that eleventh cell of mine, and wait till I come back. She soared up skywards, fussily, cleared the cliff's head, circled three times about, and set a straight course south.

"Good riddance!" said the Mistress of the Robes.

"They're like that everywhere," said Spinipes. "What are her nurseries to me? Black Queens and black sand go together. Now this is red sand. I feel the grip and bind of it."

In Sand, Ma'am, in Sand. See, she's starting now

She was quite right. The ledge was rain-washed silt. Sunshine had bleached the outer crust of it, but, under this, its substance was brick-red—fine ground stuff too, damp, clingy, easily tunnelled, and easily smarmed into a hold-fast mortar.

"In that case," said the Mistress of the Robes, "I may as well be going."

Slowly she floated off the ledge, yet kept her face towards it. Slowly she tacked from side to side, in dipping, widening sweeps. Slowly she passed the cliff's east edge, and disappeared.

Then Spinipes commenced to dig in earnest.

"Well, call me when it comes," said the Black Queen

Her scissor-jaws worked viciously, carved four-square pellets from the sun-baked crust, gripped them and flung them backwards. As she engaged the softer soil, she added feverish foot-work, and scraped, and rasped, and scrabbled it, and kicked it back in dust-clouds. Her head was quickly buried, next her waist, and, presently, she disappeared completely.

But not for long.

She backed up to the surface, dragging a sand-load underneath her body. She shook this clear, and, without resting, dived afresh. Ten loads in all she raised, and each one meant a longer spell below. For she had more to do than dig. From end to end her shaft must needs be glazed—and this meant patient mouth-work, deft steadying touches as the mortar set, and skill to keep her tube's round symmetry, and guide it in a gentle curve to end in quiet darkness. Three inches down she sank, and, at the bottom, drove a slant, and hollowed out a store-room.

With this the first stage ended. She left her shaft, and, poising in mid-air, made survey of the ledge. To right she swerved, to left again, outwards and back, upwards and down, until its bearings east and west, from sky above, and earth below, were rooted in her memory.

Then Spinipes commenced to dig in earnest

So far, so good—her morning's work was done, the picture of it fixed into her mind. Upwards she soared until the receding cliff shrunk to a splotch of brown. Once more she took her bearings and was satisfied, set her course east, and, with a dropping arrow's flight, came to the hill-top coppice. She landed on the bramble hedge which skirts its western clearing.

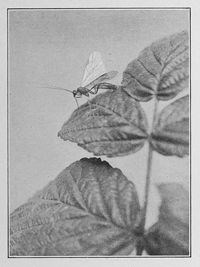

"Good hunting, sister!" said the Ophion Fly. She sat on a high briar-leaf, her rainbow wings uplifted.

"It's hardly time for that," said Spinipes. "To-morrow, p'raps. To-day I feed myself."

"There's lucerne on the slope," the Ophion said, "and something underneath you."

"Good hunting, sister!" said the Ophion Fly

There was a snap and flicker in the grass, and presently appeared a pygmy beetle, long-snouted, dusty-coated, trailing its slow legs wearily.

"D'you see it?" said the Ophion Fly.

"I see it, but what of it?"

"It means good hunting, sister. Green grubs, black-headed, fatted. Too small for me, but just the size for you. You'll find them in the lucerne."

"Thank you," said Spinipes, but she was half across the field, a dancing, filmy wisp of pink, wind-borne.

A meal, and then to work, thought Spinipes. It must be done by sunset. It must. It must.

From spray to spray she flitted. Flower after flower she robbed of its pale nectar. Bud after bud she nibbled. At last she found the food she sought, and, with her strength renewed, took flight. Upwards she soared; three times she circled round; then in a straight, unbroken course, whizzed to her shaft. Her pace was scarcely slackened as she entered. Her wings closed lengthways on her back, and, in a moment, she was at the bottom.

Something was there before her.

Something six legged, which kicked and squirmed and writhed. Something which coiled to a hard, slippery ball, and rolled away from capture.

There was no space for it to pass, and yet there seemed no holding it. At last she pinned it with her feet, and, backing, dragged it upwards to the light. It was a radiant jewel fly, a squat, short-waisted, dumpy thing made glorious by its colour. Gems sparkled on it head to tail, sapphire and ruby, emerald and topaz, and, as it struggled, fire of gold blazed and died down upon its jerking body. Instinctively she shook and worried it. Instinctively she flung it down the slope. Head over tail, tight-clenched, it spun, nor opened till it reached the grass below. Here it snapped out to shape again, took instant wing, and, with a glancing flight, regained the ledge.

"An excellent shaft, Madam; quite excellent. No doubt you made it for a special purpose. Now I–"

"Listen to me," said Spinipes, "and mark my every word. If you come near that shaft again—if you so much as touch it with your feet, I'll sting your prying life out."

She charged at it full swing and chased it off the ledge.

"An area sneak!" she muttered, as she dropt underground once more—"and over-dressed at that."

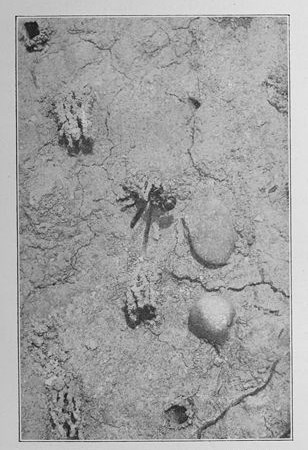

The last to cease from play was the Rose-Chafer

Below the walls showed signs of the encounter—it took ten minutes to repair their glazing. When this was done, she crept back to the entrance. It was high noon. A shimmery haze rose from the heated sand. The hum of work died fitfully away, as, one by one, the homing bees sought shade. The digger-wasps dived deep into their holes; the hunting spiders hid themselves. These were the last to cease from work; the last to cease from play was the rose-chafer.

Him the fierce blaze of heat impelled to bursts of clumsy flight. Across the pit and back again, and up and down the surface of the cliff, he whirred and swung at random. Soon even he grew listless, and crept within the shelter of the privet.

The change came with a catspaw breeze, which rippled from the valley, and, in its quiet passing, fanned the cliff.

It brought back life and energy.

Out flew the bees, a jostling, buzzing throng of them, see-sawing wildly up and down, swinging, reversing, wheeling. At length they towered and broke to work. Out crept the hunting spiders, zebra-coated; the fluttering, dancing, digger-wasps; the lightning-footed ants. Out, last of all, came Spinipes herself.

Out flew the Bees

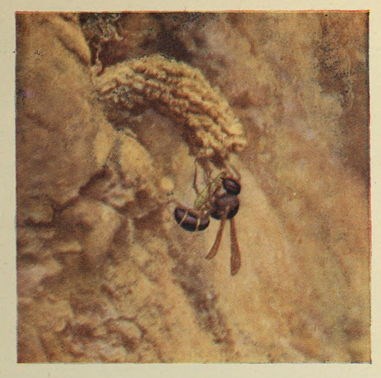

Her first care was her toilet. She combed her long antennæ out and nibbled at each foot. A circling flight to stretch her wings ended where it had started; and, in a moment, she had plunged below. Two minutes she stayed underground, then came up slowly backwards. Between her jaws was a clean-cut sand pellet. She placed it on the rim of the shaft opening, and, with deft touches from her lips, cemented it in station. She danced about it joyously, with fluttery wings, with airy, buoyant feet, moistened it here, kneaded it there. Once more she dived and dragged a second pellet up, and fixed this too upon the rim. So diving, digging, fixing, shaping, she raised a low ring-parapet.

Hour after hour she toiled

Hour after hour she toiled, tier after tier she added, gluing each pellet firmly to the last, yet leaving open space between each junction. So rose a filagree tube of sand, so fragile that a touch would crumble it; so strong that it would bear four times her weight. Before a shadow reached the cliff, it was a half-inch high. But shadows meant an end to the day's work, and Spinipes crept down below and slept.

The morning sun had shone four hours before she stirred. She peered out round-eyed from her tower, and, twisting on the rim of it, hung for a while head-downwards. A flash of green and crimson light, and something settled under her. It was the Jewel Fly again.

"Fine progress, Madam, and a first-rate tower. I never saw a better."

No word said Spinipes, but straightway launched, and flew at her.

"Out, cuckoo-sneak!" she screamed. "Out! or I sting!"

The Jewel Fly dodged like a gnat, and vanished round the corner.

She certainly meant mischief.

The lowest chamber of the shaft now held a precious thing—a spindle-shaped gold egg, slung to the side-wall by a silken thread. Back darted Spinipes to look at it; and test the fine-spun sling again; and fuss with it; and feel that it was hers.

The lowest chamber of the shaft now held a precious thing

Then up to her look-out once more. This time she dropped down to the sand and sunned herself contentedly.

The Bees had long been working. Forward and back they passed unceasingly, now and again one towered, now and again one settled; but never did their labour-song, a droning, buzzing, humming chanty, weaken or gather strength. The Jewel Fly had vanished altogether, yet Spinipes still seemed to fear her coming. A full half hour she stayed on guard, and spent the time in adding to her tower, and rounding off its entrance, which, of its own weight, took a gentle down-curve. Then, after one last gaze upon her egg, she flew afield.

"Good hunting, sister!" said the Ophion Fly. She sat on the same leaf as yesterday.

"I want them now," said Spinipes.

"The're thousands of them, thousands," said the fly, "and most of them quite fat."

It was a flabby, green, black-headed Grub

But Spinipes was too engrossed to hear her. Already, swayed by instinct she was hunting, hunting an unknown quarry in the lucerne. From plant to plant, from leaf to leaf, she fluttered. Now she dropped down to earth, and ran this way and that in the green twilight tangle. Now she sped nimble-footed up a stalk. Now she took flight and skimmed above the leaves.

At last she paused, her every muscle trembling, and stared at what confronted her.

It was a flabby, green, black-headed grub, fixed slug-like on its food-plant. A trail of skeleton tracery marked where its jaws had passed, and, as it reached the border of its leaf it swung its head, and starting near midrib, gnawed yet another ribbon-strip of green.

It ceased to feed as Spinipes appeared, and rested motionless, until her weight made its leaf-platform shiver. Then it dropped silently to earth. But Spinipes reached earth almost as fast, and, quartering every inch of ground, found it and gripped it tightly. It struggled feebly as she pinned it down, and, as she stung it, shuddered. The sting was measured to the millionth part. It robbed the grub of sentient life, yet left it living. So Nature had enjoined. For every infant Spinipes, a score of live green grubs. Robbed of full life, lest struggling they should harm the egg; forbidden death, lest dying they should taint the shaft; lulled to long sleep in mercy. Of Nature's ordinance the grub knew nothing—and Spinipes knew nothing. Her task was to make store of food against the time when her gold egg should hatch. Instinctively she knew the grub was food: instinctively she paralysed its being: instinctively she laboured to transport it.

Her jaws were fastened tight behind its head. Slowly she dragged it up a stalk until blue sky alone was over her. Then, loosing her mouth-grip of it, and clasping it with all six legs, she soared on high; one long unbroken down-glide brought her to her tower. An instant's pause to shift her grip, and she had pushed the grub within the entrance. Keeping a foot-hold on it, she eased it gently downwards, until it lay beneath her egg. She turned it over on its back and propped it to the side wall, caressed her egg, and mounted to the light again.

Back to the lucerne field she flew, and, in ten minutes, reappeared, a second grub beneath her.

This, too, she propped up carefully, and so she worked throughout the day, hunting, benumbing, storing. Twelve grubs in all she brought. All twelve she packed into a single pile. A few made feeble movements, and these, for prudence' sake, she stung afresh.

She passed the night contentedly, for it had been good hunting.

An instant's pause to shift her grip, and she had pushed the grub within the entrance.

"Take that—and that—and that," said Spinipes, and drove her sharp sting home.

Twelve Grubs in all she brought

The morrow's sky was wind-swept. Across it scurried wisps of grey with torn and fretted edges. These raced to catch each other, and fused in rounded velvet clouds. Mass joined to mass, and, surging slowly upwards, veiled the sun. Southwards, where earth met sky, a fine-drawn streak of blue endured, while, here and there, a rent across the veil gave passage to a radiant fan-spread beam. Once only did such radiance reach the cliff. It brought a treacherous message. Out swarmed the bees to snatch the chance of work, and out, with like intent, came Spinipes. Straight to her hunting-ground she flew, but, even as she reached it, came the rain.

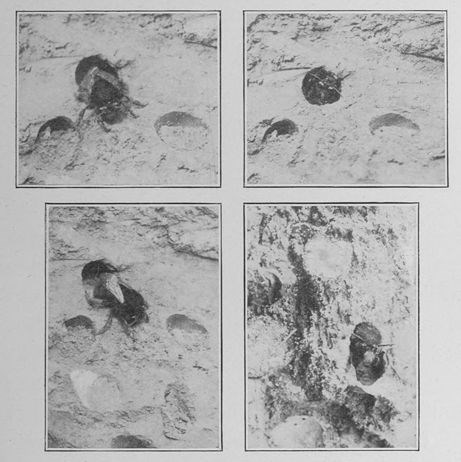

For two hours she was weather-bound. At last a watery gleam of light, mirrored in every dripping leaf, enticed her from her shelter. Homeward she sped, and, reaching home, found havoc. Her tower was gone—the rain had razed it utterly—but there was worse mishap than this. Swift-scurrying on the surface of the sand were gangs of ants, and every gang was busy with a grub, one of her grubs. They pulled and pushed and shouted to each other, and worked their burdens upward to the cleft which marked their city's entrance. She poised aghast, as with a mocking spit at her, the gaping shaft disgorged another grub. Six sturdy ants came with it, and, ranging up in order, (a pair to tug, a pair to push, a pair to guide,) commenced their long ascent.

The grubs might be replaced in time—what of her precious egg? Downwards she tumbled headlong. Three grubs, the lowest of the pile, were left; her egg— She had been in the nick of time. Her egg was there, nay more, it was uninjured. Her mother instinct told her this as, with quick trembling passes, she felt the hang and weight of it. Her mother instinct swung her round, as down the shaft she heard a scraping footfall. Even as she turned, an ant's black face peered round the lower bend.

"Out thief!" she cried. "Assassin! Bandit! Robber!"

The ant retreated hurriedly, but all that night she sat at the shaft's mouth, and barred the way below with her own body.

Next day the weather mended—a blaze of sun from an unclouded sky, and, on the sand-cliff, ecstasy of life.

Hard work in store for Spinipes! Three hours she spent in raising a fresh tower, five hours in reprovisioning her burrow. But she no longer worked alone. For others of her race had found the cliff, and other towers, twin to her own, were rising from the sand-ledge. Between them pygmy digger wasps dug shafts to match their bodies, and trident-tailed ichneumons sailed about them, and sneaking, prying, jewel flies, here, there, and everywhere on mischief bent.

She caught her old acquaintance, caught her in the act, and dragged her out, and stung her as was promised.

"I looked inside, that's all—that's really all," whimpered the culprit as she clutched the rim.

"Take that—and that—and that," said Spinipes, and drove her sharp sting home. But jewel flies are toughened folk, and this one, flung aside at last, was in full flight, and merry as a grig, within a minute of her punishment.

Daily the work grew harder. It took more time to find the grubs, since other wasps were hunting, and soon the increasing bulk of them taxed her full powers of flight. Once, as she neared the ledge, she dropped her burden. It lay where it had fallen till it died, for neither she nor other of her kind had wit to forge, or mend, a link in instincts broken chain. Once she found strange additions to her store. A human hand had robbed a neighbouring shaft and, with well-meant intention, sought to help her. Vain fancy! Here the self-same chain (to hunt—to catch—to bring—to store) was, end for end, reversed. The alien grubs were, one by one, dragged forth, and, one by one, flung headlong.

SHE SANK FIVE OTHER CURVING SHAFTS AND BUILT FIVE TOWERS TO GUARD THEM

Within a week the burrow held full store, a stack of five-and-twenty grubs piled up to meet the egg. This last was at the hatching-point. The silken cord, by which it hung, had lengthened with its growth, and each hour found it closer to its food. All had gone well, and Spinipes' last task, to seal the shaft with a partition-wall, was soon accomplished. Nor did she ever see that egg again. In time the tower itself fell in—I fancy that she helped it, and in its falling, smothered the main entrance.

She sank five other curving shafts—each held an egg—and built five towers to guard them. She made five further stores of grubs; and then, her life-work ended, she crept into a cleft and died.

What of the eggs? you ask. They hatched to golden yellow grubs, which fattened on the food stores, and when, at length, their food was all consumed, they spun them silken coverlets, and changed from grubs to sleeping nymphs. They slept through autumn's dreariness, through winter's cold, through spring's soft showers, and, when at length the warmth of summer beckoned, they burst their bonds, and, working through the sand, flew forth, as those before them had flown forth. So recommenced the cycle. An æon back it was the same. An æon hence—who knows?

PICTURES ON BUTTERFLIES' WINGS

(JULY)

The Magpie Moth

I HAVE already told you of the beautiful colours to be found on butterflies' wings, and how people have actually used a butterfly paintbox to make pictures with. Now I am going to show you some butterflies and moths (quite common ones all of them) which have queer little pictures on their wings ready made—real pictures I mean, faces and animals and things like that.

You may find it, at first, a little hard to see them, for they are puzzle pictures, like those you get in crackers, but once you have found the face, or whatever it may be, you won't be able to help seeing it.

I will start you with quite an easy one. Some of you, I expect, have noticed how often living creatures have a pattern on them like an open eye. This is called an "eye-marking," and is of course quite a different thing from the eye which is used for seeing with. Nearly all our butterflies have an eye-marking somewhere on their wings, and we find it in many other creatures besides butterflies. In birds, for instance (you will remember the peacock at once), and fish (next time you pass a big fishmonger's look out for a John Dory, he has a beauty) and lizards and snakes and frogs and things like that. It is not often seen on animals, though a leopard's or a jaguar's spots are something very like it.