полная версия

полная версияA Book of Nimble Beasts

His nose was bleeding as he started home, and he was hot and thirsty. He headed straight for water. A ten-yard down-slant brought him to the brook. He drank his fill, then, tempted by the coolness, set off swimming. He swam as deftly as a water-shrew, high out of water, with his stumpy tail cocked upward in his wake.

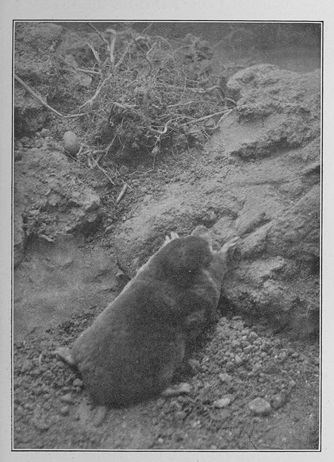

THE BANK ROSE STEEPLY OVER HIM

He reached the farther side without mishap, rustled the moisture off his fur, then started climbing. The bank rose steeply over him, but here and there a naked root gave hand-hold, and, shoulder-hoisted over these, he scrambled to the level. On this he travelled easily, using his paddle-hands as sweeps, and scuttling with his feet. From the brookside half-way across the field, and almost to the dried-up middle-ditch, bent grass-stems marked his trail. He checked close by the alder-stump, nosed at the ground, and started digging.

Perhaps he scented supper.

The alder-stump is populous still. Its core, now sapless, lifeless touchwood, is riddled through and through. Here moths-to-be, and flies-to-be, and beetles-to-be have spent their youth and fattened. Virtue still lingers in the roots, and, hidden by the forks and bends of them, quiet lives consume, or bide their time. Now and again a human hand "collects" them, now and again a mole, the skilfullest pupa hunter in the world.

Yet Bartimæus was not really hungry—he dug more from ill-humour, wrenching the grass-tufts sideways with his teeth, and slashing fiercely with his hands, until he forced an entrance for his shoulders.

Then his whole action changed.

He stabbed his nose into the soil, and, twisting from the shoulders, screwed it home. Then he drew back his head, turned over sideways, and, with one shoulder and one hand thrust out, gained purchase where his nose had been, and scratched at the soft earth. As one side tired he turned about, and thrust its fellow forward. Sometimes he lay upon his back, and heaved and squirmed and shuffled. Sometimes he screwed his way, his whole frame twisted spirally, half prostrate, half supine.

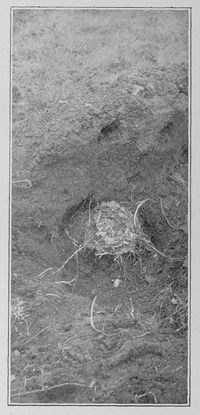

He drove a six-inch downward slant, then, for one yard, a level course, then upwards half a foot again. His pink nose broke the surface crust, snuffed, and dropped back. The first stage was accomplished, but only the first stage. His tube was choked and littered end to end. He backed nine inches through the loose, reversed, ducked down his head, and charged. Part of the rubble caked as he drove past, and part was swept before him to the outlet. It spurted through and sprayed upon the grass. Six charges raised a mole hill, and left a half-yard tunnel clear. His hands compressed the sides of it to smoothness.

He made a cave and four runs leading from it. Three plunged deep down, and hillocks marked their course. The fourth was near the surface. Its flimsy roof, pressed upwards from below, and dotted end to end with spits of soil, cast a betraying shadow.

It was good feeding-ground. In it were worms innumerable, slow-minded worms which held their ground too long, and footless leathern-coated grubs, grubs of beetles and flies, and eggs innumerable, grasshoppers' eggs, earwigs' eggs, and eggs of smaller fry, some massed in sticky clutches, some dispersed.

He toiled and fed alternately. He made a nest inside his cave, a mass of leaves and grasses dragged down into his surface run (to thrust his mouth out was sufficient), and pulled or pushed into their proper station.

This done he slept, his head tucked down between his hands, his hind feet curled up under him.

All but his ears slept soundly.

*****One-Two—One-Two—One-Two. Twin footfalls almost over him, and with them a soliloquy deep-toned.

"Comin' right down valley they be. That's them water-works. Down goes springs. Up comes nunkey-tumps. I'll get this one for sure. Here! Tatters!"

Out like a loosened spring leapt Bartimæus, and plunged into his surface run. Half-way along it he stopped dead and listened, the tip of his pink nose thrust through the roof.

Man's booted tread he knew full well; man's voice he knew, but something else was coming,—something which lilted pit-a-pat, something with yielding velvet pads, something four-footed. It danced towards him, louder still and louder, till a hoarse whisper checked it. "Steady you fool! Here good dog! Steady!"

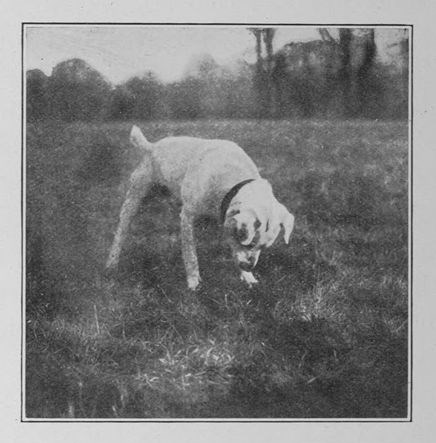

The pink nose dropped. Only one grass-blade stirred, but Tatters saw it.

His every muscle tautened as he pointed. His hair stood stiff upon his back, his eyes stared fixedly.

Only one grass-blade stirred, but Tatters saw it

For half a minute he stood tense; then Bartimæus breathed, and at his breath a grass-stem twitched and flickered.

Tatters upreared and poised himself, stayed poised a moment, then, with a vicious dropping lunge, stabbed with his forefeet downward. His muzzle followed instantly, and screwed and ploughed along the run until the weight of roof upcurled checked further progress.

Then only did he raise his head and look back shamefaced at his master. He had completely missed.

"Tatters, you'm grown old, I reckon—like your Master. Never mind, lad, we'll have 'im yet. We'll put a trap down tea-time. Come off it now! Think you can scratch him out?"

Tatters was burrowing tooth and nail, uprooting grass clumps with his teeth, drumming with his forefeet, and showering sods between his hind feet backwards. He raised a wistful, mud-stained face and whined, shook himself doubtfully, started, turned back for one more scratch, then galloped to his master's call.

And Bartimæus had been burrowing too—opening a bolt-hole which should close behind him, passing the dislodged earth beneath himself, and piling it to cover his retreat.

Tatters had all but pinned his body, and that would have meant death to him. Tatters had pinned his tail, but, with a wriggle, he had freed himself, out-distanced the pursuing nose, dived through the nest, and twisting sharply right, reached the west outlet shaft. Fist over feet he scuttled down and screwed himself into the blinded end. He bored two yards zigzagging, then paused for breath. He pricked his stumpy whiskers up, starred the grey fur about his eyes, spread wide his pinhole ears. He was quite safe. The ground before, behind, and on all sides of him, was dead. Ten minutes passed before he moved, then he worked quickly upwards, and broke the ground beneath a clump of thistles.

"They've gone," said a small piping voice above him.

The nose of Bartimæus, pink and quivery, had issued first, his bullet head had followed, then his great hands and shoulders. The sunbeams played upon his coat, and waves of limpid shimmery blue crept softly to and fro in it.

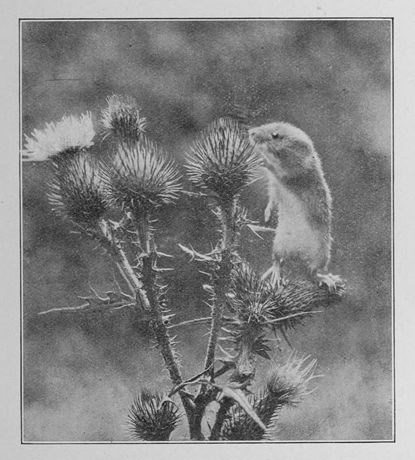

"They've gone," the Harvest Mouse repeated.

"Excellent!" said Bartimæus. "I can't see who I am talking to—this awful glare!—but it will pass—and meanwhile I can guess at you. You are a mouse; a small mouse, with sharp-pointed toes, a blunted tail, and a warm-orange coat."

"How did you know that?" said the Harvest Mouse.

"I heard you, and I felt you, and I smelt you," said Bartimæus. "You ran up just before I put my nose out. I heard your tail flick after you. I heard the leaves crack underneath your feet. I felt and smelt your colour. If you lived underground like me, you'd notice things."

"Give me the sunshine," said the Harvest Mouse (its beauty doubled on her coat). "If you could see what I can see you'd go back home."

"How's that?" said Bartimæus.

"It's near the fence," the Harvest Mouse replied, "you'd better run and look at it."

"It would take a lot to scare me," said Bartimæus, and puffed his little chest out. His chest was like the mouse's back, warm orange.

"This will scare you," she said. "You strike from here towards the sun and you can't miss it. It throws a shadow at you."

"I'm off," said Bartimæus, and straightway started burrowing.

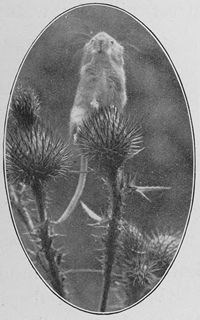

The Harvest Mouse stood up full length, and watched his ripple fading into distance. Then she dropped down to earth.

"That was a quite nice Mole," she said, "it really is a pity."

A surface run is child's play to a Mole. He bores it almost at his surface pace. The roof springs ready-moulded from his back, and lengthens like a paid-out rope behind him.

The fence was reached so suddenly that Bartimæus stubbed his nose against it. He bit and tore it, thinking it was root, then, finding it too hard for him—it was red teak—worked ten yards back and thrust his head and shoulders above ground.

The Harvest Mouse stood up full length

The sun was low behind the fence. The shadow of it lengthened out towards him and, in between its clefts, crept dazzling gold-red rays. For full ten minutes Bartimæus' head swayed nodding side to side. Now and again he twitched one hand impatiently. He fought for a clear vision. Each time he faced the dazzling streams of light, his head fell worsted sideways, and minutes passed before he could look up again.

At last their brilliance faded, and, somewhat to the right of him, a stunted bush took shape.

The stem of it loomed dark in the fence shadow; the leaves were darker still—and there was something queer about the leaves. They were too large, too black, too solid.

The breeze could hardly stir them, and, when they stirred, it was as though they spun.

No more could be determined certainly. He left his run bent on a closer vision.

It was no bush at all. It was a thick-stemmed alder-branch staked in the soil. The leaves were moles—moles like himself, or rather moles which had been like himself. For all were dead. Their bodies dangled pitifully, or, with poor shrivelled outstretched hands, spun as the breeze compelled them.

It was too much for Bartimæus' nerves. He turned about and fled, crashed luckily through his own tunnel's roof, and ran as though mole-ghosts were at his heels.

And something ran ahead of him, and reached the thistle half a yard in front.

The Harvest Mouse drew herself up indignant

"Did you find it?" said the Harvest Mouse. She sat at her old station nibbling.

"You beast," said Bartimæus, "you heartless little beast."

The Harvest Mouse drew herself up indignant.

"You're blinder than I thought," she said.

"It was a mean trick," muttered Bartimæus.

"It was a good turn," said the Harvest Mouse.

"Now listen, for I know this meadow end to end. It is no place for Moles. Ask the red-coated Meadow Mouse. Ask the Pygmy Shrew. Ask any one who really knows. Worse things than dogs come into it."

"Weasels!" said the Meadow Mouse

"Weasels!" said the Meadow Mouse. "Oh, never wait for weasels in a run. I really thought that you were one behind me." This to Bartimæus.

"Cats!" said the Pygmy Shrew. Vainly did Bartimæus strive to see her—a sorrel leaf concealed her, head to tail.

"Worse than dogs. Worse than weasels. Worse than cats," said the Harvest Mouse. "TRAPS!"

"We Harvest Mice are never trapped, and stump-tail mice are only trapped by chance—or their own folly. I saw one once. He walked inside because it rained in torrents. Down went the door, and he was drowned, with cheese afloat all round him."

"Cheese is good," said the Meadow Mouse.

"Cheese is glorious," said the Pygmy Shrew.

"There you are. You'd go anywhere for cheese," said the Harvest Mouse. "One bite—a snap behind—and then where are you?"

"I'm out in front," said the Pygmy Shrew.

"You'll try that once too often," said the Harvest Mouse.

"Now I hate cheese—the smell of it spells danger. But there are traps and traps—and the worst traps are traps with nothing in them."

"That's so," said the Meadow Mouse.

"You can smell them, can't you?" said Bartimæus.

"You can smell them if you go slow enough," said the Harvest Mouse, "but when do you go slow? Now mark my words. It's just about your sleeping time. You'll sleep for your full hour, then you'll wake hungry. You'll rush full tilt until you reach your slant. You'll rush down that, you'll rush along your gallery. Won't you now?"

"P'raps," muttered Bartimæus. He had withdrawn his nose below, and sleep was stealing over him.

"Well, don't!" said the Harvest Mouse.

"Don't!" said the Meadow Mouse.

"Don't!" said the Pygmy.

"Don't what?" said Bartimæus in his sleep.

"Don't rush!" said the Harvest Mouse. "Don't rush. Don't rush!"

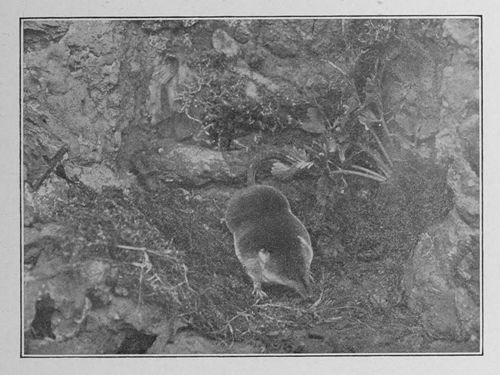

*****He slept for his full hour and woke to find the Pygmy at his side. "It's in your centre gallery," she whispered. "I've slipped right through it twice."

"My centre gallery?" shouted Bartimæus. "My centre gallery? I'll have my centre gallery clear."

He started burrowing straightway.

"Don't rush!" the Pygmy screamed behind. "Don't rush! It's death to rush!"

And yet it was his rush that saved him.

"Don't rush!" the Pygmy screamed behind

The crumbled earth which still lay in the bolt-hole, melted before it. Part slipped to either side of him. Part massed before his plunging head, and, reaching the clear downshaft, dropped. With it there dropped a stone—a rounded half-inch stone, which danced along the gallery at the foot, cannoned from side to side of it, spun round and pulled up short, six inches in advance of him. His senses signalled something in his path. His senses signalled a clear passage through it, and a clear space beyond it. His senses urged more pace. So he crashed on. He stubbed his hands against a ring of iron: the ring gave way: there was a snap and two iron jaws had gripped his waist. But for the stone which jammed against the clinch of them, he must have met his death. And death itself had scarcely brought more torture. It was as though the half of him sped on while half remained behind. The back wrench left him senseless, and so the Pygmy found him. It was the pit-pat of her on his fur, the cobweb flutter of her questionings, which roused him back to life.

His Fortress, his own Fortress, had been breached

"I'm done," he muttered, "done as sure as sure."

"Not you!" she answered bravely, "the trap's not closed—not half. Wriggle, dear Uncle, wriggle!"

And Bartimæus wriggled.

He wriggled right; he wriggled left; he wriggled up; he wriggled down; he brought his hands to bear upon the iron and with a supreme twist he wriggled free.

Then he saw red.

He flung himself against the trap, and bit at it, and scratched at it, and shook it with his shoulders, and heaved and strained and wrenched at it, until it lay upturned upon the surface. He was convulsed with windy gusts of rage: nose-tip to tail he boiled; nor did he gain composure until the field was far behind, and he had reached the smooth-faced tube which led to his own fortress. Hand over foot he sped the length of it, dived down the U-shaped entrance hole, bobbed up again and climbed into his nest.

His troubles were not over.

His fortress, his own fortress, had been breached. The nest lay open to the day, windswept.

For a full hour he toiled repairing it, then, mole-tired, coiled to sleep.

SOMETHING ABOUT A CHAMÆLEON

(NOVEMBER)

"''Tis green! 'tis green, Sir, I assure ye.''Green!' cries the other in a fury.'Why, Sir, d'ye think I've lost my eyes?'''Twere no great loss,' the friend replies,'For if they always serve you thus,'You'll find them but of little use.'"I WONDER how many of you know these lines? Not so very long ago most young people used to have to learn the poem from which they are taken, but I don't think the poem can be quite such a favourite as it used to be. Perhaps we are all getting to be such good naturalists that we know it is not quite true, for, though Chamæleons change their colours in a very wonderful way, they do not go red, white, and blue, in the way which the poem makes out.

I think I must tell you a little story about a Chamæleon, though some of you may perhaps have heard it before. An old lady once had a pet Chamæleon which she was very fond of, and which her manservant, John, used to look after. He was very fond of the Chamæleon too, and he used to amuse himself by putting it on to different coloured things in his room and watching it change colour. Well, one day, the old lady had a friend to tea, and she thought she would like to show her the Chamæleon, so she rang for John.

"John," she said, "bring in the Chamæleon."

John looked very sorry for himself. "Please ma'am," he said, "I can't."

"Can't?" said his mistress. "Why not?"

John looked still more confused. "Please, ma'am," he said, "he's gone."

"Why, how is that?" said the lady.

"Well, ma'am, I was playing with him, and I put him against my baize apron, and he turned green."

"Well?"

"And then I put him against the red tray, ma'am, and he turned red."

"Yes, yes! Of course he would."

"And then I put him against your tartan plaid, ma'am, and—and he just bust hisself."

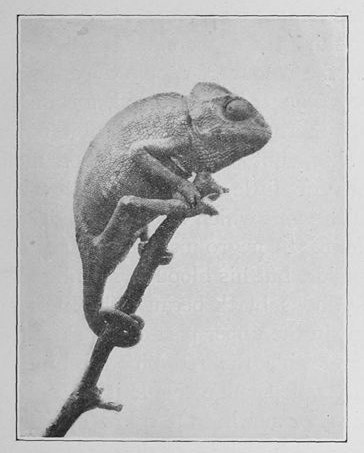

You can see his Eye looking back over his Shoulder in this Picture

I am afraid that that story is not altogether true either.

I must try to explain to you how a Chamæleon changes colour. Of course you all know that there are black men, and brown men, and copper-coloured men, and yellow men, and what we call white men; and you know, too, that among white men some have much darker skins than others.

Now the colour of people depends a little on the colour of their blood, for there is a network of tiny veins in the lower part of their skin, but it depends even more on millions of little specks of yellowish and brownish paint which lie in the upper part of their skin. A negro may be as black as your hat outside, but his blood is red all the same, and he looks black because the little specks of paint in the upper part of his skin are very dark and hide the red blood behind them. When people change colour it is because for one cause or another the colour of their blood can be more plainly, or less plainly, seen; and, when this cause is taken away, their old colour returns, for the little specks of paint have not altered in themselves at all.

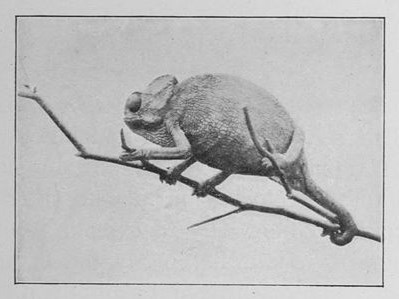

You can see his Hands and Feet well in this Picture

In Chamæleons, however, and several other creatures, which change colour much more than we do, and keep their changed colour for quite a long time, the specks of paint lie in the lower part of the skin, and often there are numbers of them clustered together as if they had been pressed down tight into little bags. These clusters of paint specks have the power of branching out like sea anemones, and afterwards pulling themselves together again like sea anemones when they are frightened. When they are spread out so as to be as large as possible, the Chamæleon is dark-coloured; and when they are drawn in so as to be as small as possible, the Chamæleon is light coloured; and when, as is really most usual, they are spread out in one part of his body and drawn in in another, the Chamæleon is piebald. I expect you will be curious to know what colour the specks of paint are, and whether they are always the same. They are so small that one needs a powerful microscope to see them; but, as far as we can tell, they are always brownish or reddish, so that the greens and blues which are often to be seen in patches on a Chamæleon have to be accounted for in some other way. It would take too long to explain the blues and greens to you thoroughly, but I think I can give you one little hint about them. You all know what mother-of-pearl looks like. If you hold a piece one way it seems a dull grey all over, but if you hold it another you see all the colours of the rainbow, and you can even make the colours move about it if you handle it properly. Now if the colours were paint they would not move about, though they might not be so bright in some positions as in others, and for the present you must be satisfied to know that a Chamæleon skin, besides holding clusters of paint-specks which change their shape, is so wonderfully made that it can show mother-of-pearl colours as well.

A grown-up Chamæleon is usually greenish in the daytime, with brown patches on his sides. When he goes to sleep at night he turns cream-coloured and his patches become yellowish. A baby Chamæleon is snowy white, and doesn't get spotted even when he is angry or excited, as a grown-up Chamæleon always does.

Now for the Chamæleon pictures. First you must notice his eyes. He has enormous eyeballs, but instead of having two eyelids to each, as we have, he has one eyelid to each (it is really made up of two stuck together), with a tiny round hole in the centre for his eye to look through. This is queer enough, but there is something even queerer about a Chamæleon's eyes. He can move either eyeball up or down or sideways, but he hardly ever moves both the same way, so that he has quite the most wonderful squint in the world, and often keeps one eye looking over his shoulder while the other looks straight in front of him.

Next you must look at his long, skinny arms and legs, and especially at his hands and feet. Like ourselves he has five fingers or toes on each, but they are differently arranged from ours. You must remember, of course, that our thumbs are really fingers. On each hand a Chamæleon has three thumbs and two fingers, and on each foot he has two great toes and three ordinary toes.

THE TRAIL OF NIMBLE BEASTS

(DECEMBER)

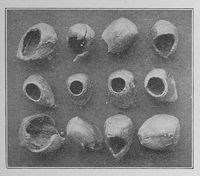

Top Row Nuts gnawed by Meadow Mice

Second Row " Dormice

Third Row " Field Mice

I AM going to end the articles in this book by telling you how you may best see for yourselves some of the queer creatures which I have photographed, for the real beasties are far, far more interesting than any photographs of them can be, and they are not so very difficult to see if only you go the right way about it. I think the Winter is as good a season as any to begin in, at any rate with the fur-folk, for there is sure to be plenty of mud, which is a splendid thing for footprints to show up on, and there may be a fall of snow, which will tell you more in a day of the coming and goings of your little brothers, than you could learn without it in a year.

If you put on your thickest boots and go out into the fields and along the hedgerows, after a heavy snowfall, you will find thousands and thousands of footprints. Most of these will be the footprints of birds, but some, you will see at once, belong to four-footed creatures. I am showing you pictures of some of the commonest of these so that you may know them the next time you see them. I have left out Bunny-Rabbit on purpose, because I think you will be able to find out what his curious footprints are like for yourselves, and will remember them better that way.