полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

How did early man come to invent the dug-out? Not only did he hollow out a tree trunk by the laborious process of burning and by chipping with a flint adze, he dressed the trunk so that his boat could be balanced on the water. The early shipbuilders had to learn, and did learn, for themselves, "the values of length and beam, of draught and sweet lines, of straight keel; with high stem to breast a wave and high stern to repel a following sea". The fashioning of a sea-worthy, or even a river-worthy boat, must have been in ancient times as difficult a task as was the fashioning of the first aeroplane in our own day. Many problems had to be solved, many experiments had to be made, and, no doubt, many tragedies took place before the first safe model-boat was paddled across a river. The early experimenters may have had shapes of vessels suggested to them by fish and birds, and especially by the aquatic birds that paddled past them on the river breast with dignity and ease. But is it probable that the first experiments were made with trees? Did early man undertake the laborious task of hewing down tree after tree to shape new models, until in the end he found on launching the correctly shaped vessel that its balance was perfect? Or was the dug-out canoe an imitation of a boat already in existence, just as a modern ship built of steel or concrete is an imitation of the earlier wooden ships? The available evidence regarding this important phase of the shipping problem tends to show that, before the dug-out was invented, boats were constructed of light material. Ancient Egypt was the earliest shipbuilding country in the world, and all ancient ships were modelled on those that traded on the calm waters of the Nile. Yet Egypt is an almost treeless land. There the earliest boats—broad, light skiffs—were made by binding together long bundles of the reeds of papyrus. Ropes were twisted from papyrus as well as from palm fibre.51 It would appear that, before dug-outs were made, the problems of boat construction were solved by those who had invented papyri skiffs and skin boats. In the case of the latter the skins were stretched round a framework, sewed together and made watertight with pitch. We still refer to the "seams" and the "skin" of a boat.

The art of boat-building spread far and wide from the area of origin. Until recently the Chinese were building junks of the same type as they did four or five hundred years earlier. These junks have been compared by more than one writer to the deep-sea boats of the Egyptian Empire period. The Papuans make "dug-outs" and carve eyes on the prows as did the ancient Egyptians and as do the Maltese, Chinese, &c., in our own day. Even when only partly hollowed, the Papuan boats have perfect balance in the water as soon as they are launched.52 The Polynesians performed religious ceremonies when cutting down trees and constructing boats.53 In their incantations, &c., the lore of boat-building was enshrined and handed down. The Polynesian boat was dedicated to the mo-o (dragon-god). We still retain a relic of an ancient religious ceremony when a bottle of wine is broken on the bows of a vessel just as it is being launched.

After the Egyptians were able to secure supplies of cedar wood from the Atlas Mountains or Lebanon, by drifting rafts of lashed trees along the coast line, they made dug-out vessels of various shapes, as can be seen in the tomb pictures of the Old Kingdom period. These dug-outs were apparently modelled on the earlier papyri and skin boats. A ship with a square sail spread to the wind is depicted on an Ancient Egyptian two-handed jar in the British Museum, which is of pre-dynastic age and may date to anything like 4000 or 5000 b.c. At that remote period the art of navigation was already well advanced, no doubt on account of the experience gained on the calm waters of the Nile.

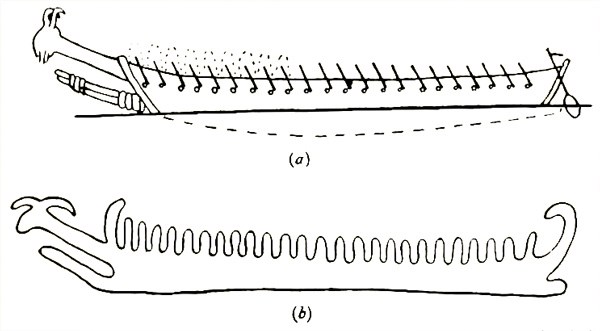

(a) Sketch of a boat from Victoria Nyanza, after the drawing in Sir Henry Stanley's Darkest Africa. Only the handles of the oars are shown. In outline the positions of some of the oarsmen are roughly represented.

(b) Crude drawing of a similar boat carved upon the rocks in Sweden during the Early Bronze Age, after Montelius. By comparison with (a) it will be seen that the vertical projections were probably intended to represent the oarsmen.

The upturned hook-like appendage at the stern is found in ancient Egyptian and Mediterranean ships, but is absent in the modern African vessel shown in (a).

These figures are taken from Elliot Smith's Ancient Mariners (1918).

The existence of these boats on the Nile at a time when great race migrations were in progress may well account for the early appearance of dug-outs in Northern Europe. One of the Clyde canoes, found embedded in Clyde silt twenty-five feet above the present sea-level, was found to have a plug of cork which could only have come from the area in which cork trees grow—Spain, Southern France, or Italy.54 It may have been manned by the Azilians of Spain whose rock paintings date from the Transition period. Similar striking evidence of the drift of culture from the Mediterranean area towards Northern Europe is obtained from some of the rock paintings and carvings of Sweden. Among the canoes depicted are some with distinct Mediterranean characteristics. One at Tegneby in Bohuslän bears a striking resemblance to a boat seen by Sir Henry Stanley on Lake Victoria Nyanza. It seems undoubted that the designs are of common origin, although separated not only by centuries but by barriers of mountain, desert, and sea extending many hundreds of miles. From the Maglemosian boat the Viking ship was ultimately developed; the unprogressive Victoria Nyanza boatbuilders continued through the Ages repeating the design adopted by their remote ancestors. In both vessels the keel projects forward, and the figure-head is that of a goat or ram. The northern vessel has the characteristic inward curving stern of ancient Egyptian ships. As the rock on which it was carved is situated in a metal-yielding area, the probability is that this type of vessel is a relic of the visits paid by searchers for metals in ancient times, who established colonies of dark miners among the fair Northerners and introduced the elements of southern culture.

The ancient boats found in Scotland are of a variety of types. One of those at Glasgow lay, when discovered, nearly vertical, with prow uppermost as if it had foundered; it had been built "of several pieces of oak, though without ribs". Another had the remains of an outrigger attached to it: beside another, which had been partly hollowed by fire, lay two planks that appear to have been wash-boards like those on a Sussex dug-out. A Clyde clinker-built boat, eighteen feet long, had a keel and a base of oak to which ribs had been attached. An interesting find at Kinaven in Aberdeenshire, several miles distant from the Ythan, a famous pearling river, was a dug-out eleven feet long, and about four feet broad. It lay embedded at the head of a small ravine in five feet of peat which appears to have been the bed of an ancient lake. Near it were the stumps of big oaks, apparently of the Upper Forestian period.

Among the longest of the ancient boats that have been discovered are one forty-two feet long, with an animal head on the prow, from Loch Arthur, near Dumfries, one thirty-five long from near the River Arun in Sussex, one sixty-three feet long excavated near the Rother in Kent, one forty-eight feet six inches long, found at Brigg, Lincolnshire, with wooden patches where she had sprung a leak, and signs of the caulking of cracks and small holes with moss.

These vessels do not all belong to the same period. The date of the Brigg boat is, judging from the geological strata, between 1100 and 700 b.c. It would appear that some of the Clyde vessels found at twenty-five feet above the present sea-level are even older. Beside one Clyde boat was found an axe of polished green-stone similar to the axes used by Polynesians and others in shaping dug-outs. This axe may, however, have been a religious object. To the low bases of some vessels were fixed ribs on which skins were stretched. These boats were eminently suitable for rough seas, being more buoyant than dug-outs. According to Himilco the inhabitants of the Œstrymnides, the islands "rich in tin and lead", had most sea-worthy skiffs. "These people do not make pine keels, nor", he says, "do they know how to fashion them; nor do they make fir barks, but, with wonderful skill, fashion skiffs with sewn skins. In these hide-bound vessels, they skim across the ocean." Apparently they were as daring mariners as the Oregon Islanders of whom Washington Irving has written:

"It is surprising to see with what fearless unconcern these savages venture in their light barks upon the roughest and most tempestuous seas. They seem to ride upon the wave like sea-fowl. Should a surge throw the canoe upon its side, and endanger its over turn, those to the windward lean over the upper gunwale, thrust their paddles deep into the wave, and by this action not merely regain an equilibrium, but give their bark a vigorous impulse forward."

The ancient mariners whose rude vessels have been excavated around our coasts were the forerunners of the Celtic sea-traders, who, as the Gaelic evidence shows, had names not only for the North Sea and the English Channel but also for the Mediterranean Sea. They cultivated what is known as the "sea sense", and developed shipbuilding and the art of navigation in accordance with local needs. When Julius Cæsar came into conflict with the Veneti of Brittany he tells that their vessels were greatly superior to those of the Romans. "The bodies of the ships", he says, "were built entirely of oak, stout enough to withstand any shock or violence.... Instead of cables for their anchors they used iron chains.... The encounter of our fleet with these ships was of such a nature that our fleet excelled in speed alone, and the plying of oars; for neither could our ships injure theirs with their rams, so great was their strength, nor was a weapon easily cast up to them owing to their height.... About 220 of their ships … sailed forth from the harbour." In this great allied fleet were vessels from our own country.55

It must not be imagined that the "sea sense" was cultivated because man took pleasure in risking the perils of the deep. It was stern necessity that at the beginning compelled him to venture on long voyages. After England was cut off from France the peoples who had adopted the Neolithic industry must have either found it absolutely necessary to seek refuge in Britain, or were attracted towards it by reports of prospectors who found it to be suitable for residence and trade.

CHAPTER VIII

Neolithic Trade and Industries

Attractions of Ancient Britain—Romans search for Gold, Silver, Pearls, &c.—The Lure of Precious Stones and Metals—Distribution of Ancient British Population—Neolithic Settlements in Flint-yielding Areas—Trade in Flint—Settlements on Lias Formation—Implements from Basic Rocks—Trade in Body-painting Materials—Search for Pearls—Gold in Britain and Ireland—Agriculture—The Story of Barley—Neolithic Settlers in Ireland—Scottish Neolithic Traders—Neolithic Peoples not Wanderers—Trained Neolithic Craftsmen.

The "drift" of peoples into Britain which began in Aurignacian times continued until the Roman period. There were definite reasons for early intrusions as there were for the Roman invasion. "Britain contains to reward the conqueror", Tacitus wrote,56 "mines of gold and silver and other metals. The sea produces pearls." According to Suetonius, who at the end of the first century of our era wrote the Lives of the Cæsars, Julius Cæsar invaded Britain with the desire to enrich himself with the pearls found on different parts of the coast. On his return to Rome he presented a corselet of British pearls to the goddess Venus. He was in need of money to further his political ambitions. He found what he required elsewhere, however. After the death of Queen Cleopatra sufficient gold and silver flowed to Rome from Egypt to reduce the loan rate of interest from 12 to 4 per cent. Spain likewise contributed its share to enrich the great predatory state of Rome.57

Long ages before the Roman period the early peoples entered Britain in search of pearls, precious stones, and precious metals because these had a religious value. The Celts of Gaul offered great quantities of gold to their deities, depositing the precious metals in their temples and in their sacred lakes. Poseidonius of Apamea tells that after conquering Gaul "the Romans put up these sacred lakes to public sale, and many of the purchasers found quantities of solid silver in them". He also says that gold was similarly placed in these lakes.58 Apparently the Celts believed, as did the Aryo-Indians, that gold was "a form of the gods" and "fire, light, and immortality", and that it was a "life giver".59 Personal ornaments continued to have a religious value until Christian times.

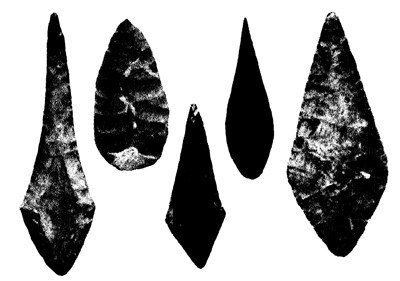

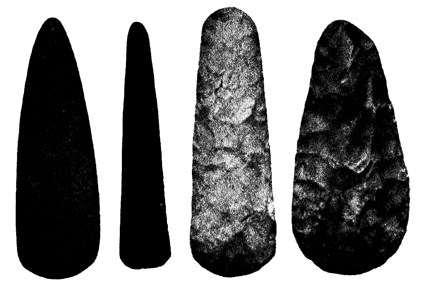

FLINT LANCE-HEADS FROM IRELAND (British Museum)

Photo Oxford University Press

CHIPPED AND POLISHED ARTIFACTS FROM SOUTHERN ENGLAND (British Museum)

As we have seen when dealing with the "Red Man of Paviland", the earliest ornaments were shells, teeth of wild animals, coloured stones, ivory, &c. Shells were carried great distances. Then arose the habit of producing substitutes which were regarded as of great potency as the originals. The ancient Egyptians made use of gold to manufacture imitation shells, and before they worked copper they wore charms of malachite, which is an ore of copper. They probably used copper first for magical purposes just as they used gold. Pearls found in shells were regarded as depositories of supernatural influence, and so were coral and amber (see Chapter XIII). Like the Aryo-Indians, the Egyptians, Phœnicians, Greeks, and others connected precious metals, stones, pearls, &c., with their deities, and believed that these contained the influence of their deities, and were therefore "lucky". These and similar beliefs are of great antiquity in Europe and Asia and North Africa. It would be rash to assume that they were not known to the ancient mariners who reached our shores in vessels of Mediterranean type.

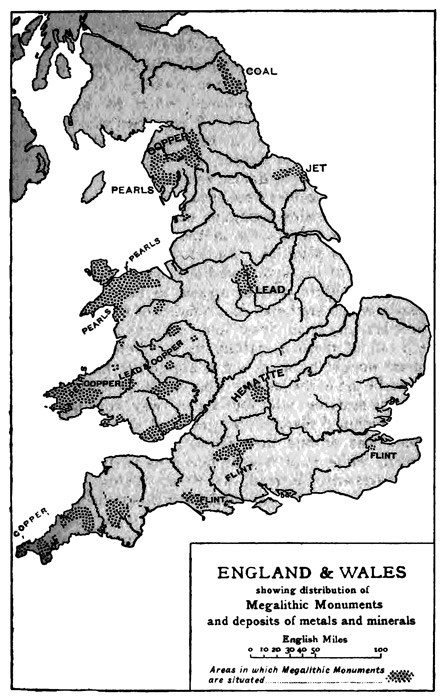

The colonists who were attracted to Britain at various periods settled in those districts most suitable for their modes of life. It was necessary that they should obtain an adequate supply of the materials from which their implements and weapons were manufactured. The distribution of the population must have been determined by the resources of the various districts.

At the present day the population of Britain is most dense in those areas in which coal and iron are found and where commerce is concentrated. In ancient times, before metals were used, it must have been densest in those areas where flint was found—that is, on the upper chalk formations. If worked flints are discovered in areas which do not have deposits of flint, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that the flint was obtained by means of trade, just as Mediterranean shells were in Aurignacian and Magdalenian times obtained by hunters who settled in Central Europe. In Devon and Cornwall, for instance, large numbers of flint implements have been found, yet in these counties suitable flint was exceedingly scarce in ancient times, except in East Devon, where, however, the surface flint is of inferior character. In Wilts and Dorset, however, the finest quality of flint was found, and it was no doubt from these areas that the early settlers in Cornwall and Devon received their chief supplies of the raw material, if not of the manufactured articles.

In England, as on the Continent, the most abundant finds of the earliest flint implements have been made in those areas where the early hunters and fishermen could obtain their raw materials. River drift implements are discovered in largest numbers on the chalk formations of south-eastern England between the Wash and the estuary of the Thames.

The Neolithic peoples, who made less use of horn and bone than did the Azilians and Maglemosians, had many village settlements on the upper chalk in Dorset and Wiltshire, and especially at Avebury where there were veritable flint factories, and near the famous flint mines at Grimes Graves in the vicinity of Weeting in Norfolk and at Cissbury Camp not far from Worthing in Sussex. Implements were likewise made of basic rocks, including quartzite, ironstone, green-stone, hornblende schist, granite, mica-schist, &c.; while ornaments were made of jet, a hydrocarbon compound allied to cannel coal, which takes on a fine polish, Kimeridge shale and ivory. Withal, like the Aurignacians and Magdalenians, the Neolithic-industry people used body paint, which was made with pigments of ochre, hæmatite, an ore of iron, and ruddle, an earthy variety of iron ore.

In those districts, where the raw materials for stone implements, ornaments, and body paint were found, traces survive of the activities of the Neolithic peoples. Their graves of long-barrow type are found not only in the chalk areas but on the margins of the lias formations. Hæmatite is found in large quantities in West Cumberland and north Lancashire and in south-western England, while the chief source of jet is Whitby in Yorkshire, where it occurs in large quantities in beds of the Upper Lias shale.

Mr. W. J. Perry, of Manchester University, who has devoted special attention to the study of the distribution of megalithic monuments, has been drawing attention to the interesting association of these monuments with geological formations.60 In the Avebury district stone circles, dolmens, chambered barrows, long barrows, and Neolithic settlements are numerous; another group of megalithic monuments occurs in Oxford on the margin of the lias formation, and at the south-end of the great iron field extending as far as the Clevelands. According to the memoir of the geological survey, there are traces of ancient surface iron-workings in the Middle Lias formation of Oxfordshire, where red and brown hæmatite were found. Mr. Perry notes that there are megalithic monuments in the vicinity of all these surface workings, as at Fawler, Adderbury, Hook Norton, Woodstock, Steeple Aston, and Hanbury. Apparently the Neolithic peoples were attracted to the lias formation because it contains hæmatite, ochre, shale, &c. There are significant megaliths in the Whitby region where the jet is so plentiful. Amber was obtained from the east coast of England and from the Baltic.

The Neolithic peoples appear to have searched for pearls, which are found in a number of English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish rivers, and in the vicinity of most, if not all, of these megaliths occur. Gold was the first metal worked by man, and it appears to have attracted some of the early peoples who settled in Britain. The ancient seafarers who found their way northward may have included searchers for gold and silver. The latter metal was at one time found in great abundance in Spain, while gold was at one time fairly plentiful in south-western England, in North Wales, in various parts of Scotland and especially in Lanarkshire, and in north-eastern, eastern, and western Ireland. That there was a "drift" of civilized peoples into Britain and Ireland during the period of the Neolithic industry is made evident by the fact that the agricultural mode of life was introduced. Barley does not grow wild in Europe. The nearest area in which it grew wild and was earliest cultivated was the delta area of Egypt, the region from which the earliest vessels set out to explore the shores of the Mediterranean. It may be that the barley seeds were carried to Britain not by the overland routes alone to Channel ports, but also by the seafarers whose boats, like the Glasgow one with the cork plug, coasted round by Spain and Brittany, and crossed the Channel to south-western England and thence went northward to Scotland. As Irish flints and ground axe-heads occur chiefly in Ulster, it may be that the drift of early Neolithic settlers into County Antrim, in which gold was also found, was from south-western Scotland. The Neolithic settlement at Whitepark Bay, five miles from the Giant's Causeway, was embedded at a considerable depth, showing that there has been a sinking of the land in this area since the Neolithic industry was introduced.

Neolithic remains are widely distributed over Scotland, but these have not received the intensive study devoted to similar relics in England. Mr. Ludovic Mann, the Glasgow archæologist, has, however, compiled interesting data regarding one of the local industries that bring out the resource and activities of early man. On the island of Arran is a workable variety of the natural volcanic glass, called pitch-stone, that of other parts of Scotland and of Ireland being "too much cracked into small pieces to be of use". It was used by the Neolithic settlers in Arran for manufacturing arrowheads, and as it was imported into Bute, Ayrshire, and Wigtownshire, a trade in this material must have existed. "If", writes Mr. Mann, "the stone was not locally worked up into implements in Bute, it was so manipulated on the mainland, where workshops of the Neolithic period and the immediately succeeding overlap period yielded long fine flakes, testifying to greater expertness in manufacturing there than is shown by the remains in the domestic sites yet awaiting adequate exploration in Arran. The explanation may be that the Wigtownshire flint knappers, accustomed to handle an abundance of flint, were more proficient than in most other places, and that the pitch-stone was brought to them as experts, because the material required even more skilful handling than flint".61 In like manner obsidian, as has been noted, was imported into Crete from the island of Melos by seafarers, long before the introduction of metal working.62

It will be seen that the Neolithic peoples were no mere wandering hunters, as some have represented them to have been, but they had their social organization, their industries, and their system of trading by land and sea. They settled not only in those areas where they could procure a regular food supply, but those also in which they obtained the raw materials for implements, weapons, and the colouring material which they used for religious purposes. They made pottery for grave offerings and domestic use, and wooden implements regarding which, however, little is known. Withal, they had their spinners and weavers. The conditions prevailing in Neolithic settlements must have been similar to those of later times. There must have been systems of laws to make trade and peaceful social intercourse possible, and no doubt these had, as elsewhere, a religious basis. Burial customs indicate a uniformity of beliefs over wide areas. The skill displayed in working stone was so great that it cannot now be emulated. Ripple-flaking has long been a lost art. Craftsmen must have undergone a prolonged period of training which was intelligently controlled under settled conditions of life. It is possible that the so-called Neolithic folk were chiefly foreigners who exploited the riches of the country. The evidence in this connection will be found in the next chapter.

CHAPTER IX

Metal Workers and Megalithic Monuments

"Broad-heads" of Bronze Age—The Irish Evidence—Bronze Introduced by Traders—How Metals were Traced—A Metal Working Tribe—Damnonii in England, Scotland, and Ireland—Miners as Slaves—The Lot of Women Workers—Megalithic Monuments in English Metal-yielding Areas—Stone Circles in Barren Localities—Early Colonies of Easterners in Spain—Egyptian and Babylonian Relics associated with British Jet and Baltic Amber—A New Flint Industry of Eastern Origin—British Bronze identical with Continental—Ancient Furnaces of Common Origin—"Stones of Worship" adorned with Metals—The "Maggot God" of Stone Circles—Ancient Egyptian Beads at Stonehenge—Earliest Authentic Date in British History—The Aim of Conquests.

It used to be thought that the introduction of metal working into Britain was the result of an invasion of alien peoples, who partly exterminated and partly enslaved the long-headed Neolithic inhabitants. This view was based on the evidence afforded by a new type of grave known as the "Round Barrow". In graves of this class have been found Bronze Age relics, a distinctive kind of pottery, and skulls of broad-heads. The invasion of broad-heads undoubtedly took place, and their burial customs suggest that their religious beliefs were not identical with those of the long-heads. But it remains to be proved that they were the actual introducers of the bronze industry. They do not appear to have reached Ireland, where bronze relics are associated with a long-headed people of comparatively low stature.