полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

Shells were thought to impart vitality and give protection, not only to human beings, but even to the plots of the earliest florists and agriculturists. "Mary, Mary, quite contrairie", who in the nursery rhyme has in her garden "cockle-shells all in row", was perpetuating an ancient custom. The cockle-shell is still favoured by conservative villagers, and may be seen in their garden plots and in graveyards. Shells placed at cottage doors, on window-sills, and round fire-places are supposed to bring luck and give security, like the horse-shoe on the door.

The mother goddess, remembered as the fairy queen, is still connected with shells in Hebridean folk-lore. A Gaelic poet refers to the goddess as "the maiden queen of wisdom who dwelt in the beauteous bower of the single tree where she could see the whole world and where no fool could see her beauty". She lamented the lack of wisdom among women, and invited them to her knoll. When they were assembled there the goddess appeared, holding in her hand the copan Moire ("Cup of Mary"), as the blue-eyed limpet shell is called. The shell contained "the ais (milk) of wisdom", which she gave to all who sought it. "Many", we are told, "came to the knoll too late, and there was no wisdom left for them."32 A Gaelic poet says the "maiden queen" was attired in emerald green, silver, and mother-of-pearl.

Here a particular shell is used by an old goddess for a specific purpose. She imparts knowledge by providing a magic drink referred to as "milk". The question arises, however, if a deity of this kind was known in early times. Did the Crô-Magnons of the Aurignacian stage of culture conceive of a god or goddess in human form who nourished her human children and instructed them as do human mothers? The figure of a woman, holding in her hand a horn which appears to have been used for drinking from, is of special interest in this connection. As will be shown, the Hebridean "maiden" links with other milk-providing deities.

The earliest religious writings in the world are the Pyramid Texts of ancient Egypt which, as Professor Breasted so finely says, "vaguely disclose to us a vanished world of thought and speech". They abound "in allusions to lost myths, to customs and usages long since ended". Withal, they reflect the physical conditions of a particular area—the Nile Valley, in which the sun and the river are two outstanding natural features. There was, however, a special religious reason for connecting the sun and the river.

In these old Pyramid Texts are survivals from a period apparently as ancient as that of early Aurignacian civilization in Europe, and perhaps, as the clue afforded by the Indian shell found in the Grimaldi cave, not unconnected with it. The mother goddess, for instance, is prayed to so that she may suckle the soul of the dead Pharaoh as a mother suckles her child and never wean him.33 Milk was thus the elixir of life, and as the mother goddess of Egypt is found to have been identified with the cowrie—indeed to have been the spirit or personification of the shell—the connection between shells and milk may have obtained even in Aurignacian times in south-western Europe. That the mother goddess of Crô-Magnons had a human form is suggested by the representations of mothers which have been brought to light. An Aurignacian statuette of limestone found in the cave of Willendorf, Lower Austria, has been called the "Venus of Willendorf". She is very corpulent—apparently because she was regarded as a giver of life. Other statues of like character have been unearthed near Mentone, and they have a striking resemblance to the figurines of fat women found in the pre-dynastic graves of Egypt and in Crete and Malta. The bas-relief of the fat woman sculptured on a boulder inside the Aurignacian shelter of Laussel may similarly have been a goddess. In her right hand she holds a bison's horn—perhaps a drinking horn containing an elixir. Traces of red colouring remain on the body. A notable fact about these mysterious female forms is that the heads are formal, the features being scarcely, if at all, indicated.

Even if no such "idols" had been found, it does not follow that the early people had no ideas about supernatural beings. There are references in Gaelic to the coich anama (the "spirit case", or "soul shell", or "soul husk"). In Japan, which has a particularly rich and voluminous mythology, there are no idols in Shinto temples. A deity is symbolized by the shintai (God body), which may be a mirror, a weapon, or a round stone, a jewel or a pearl. A pearl is a tama; so is a precious stone, a crystal, a bit of worked jade, or a necklace of jewels, ivory, artificial beads, &c. The soul of a supernatural being is called mi-tama—mi being now a honorific prefix, but originally signifying a water serpent (dragon god). The shells, of which ancient deities were personifications, may well have been to the Crô-Magnons pretty much what a tama is to the Japanese, and what magic crystals were to mediæval Europeans who used them for magical purposes. It may have been believed that in the shells, green stones, and crystals remained the influence of deities as the power of beasts of prey remained in their teeth and claws. The ear-rings and other Pagan ornaments which Jacob buried with Laban's idols under the oak at Shechem were similarly supposed to be god bodies or coagulated forms of "life substance". All idols were temporary or permanent bodies of deities, and idols were not necessarily large. It would seem to be a reasonable conclusion that all the so-called ornaments found in ancient graves were supposed to have had an intimate connection with the supernatural beings who gave origin to and sustained life. These ornaments, or charms, or amulets, imparted vitality to human beings, because they were regarded as the substance of life itself. The red jasper worn in the waist girdles of the ancient Egyptians was reputed, as has been stated, to be a coagulated drop of the blood of the mother goddess Isis. Blood was the essence of life.

The red woman or goddess of the Laussel shelter was probably coloured so as to emphasize her vitalizing attributes; the red colour animated the image.

An interesting reference in Shakespeare's Hamlet to ancient burial customs may here be quoted, because it throws light on the problem under discussion. When Ophelia's body is carried into the graveyard34 one of the priests says that as "her death was doubtful" she should have been buried in "ground unsanctified"—that is, among the suicides and murderers. Having taken her own life, she was unworthy of Christian burial, and should be buried in accordance with Pagan customs. In all our old churchyards the takers of life were interred on the north side, and apparently in Shakespeare's day traditional Pagan rites were observed in the burials of those regarded as Pagans. The priest in Hamlet, therefore, says of Ophelia:

She should in ground unsanctified have lodgedTill the last trumpet; for charitable prayers,Shards, flints, and pebbles should be thrown on her.There are no shards (fragments of pottery) in the Crô-Magnon graves, but flints and pebbles mingle with shells, teeth, and other charms and amulets. Vast numbers of perforated shells have been found in the burial caves near Mentone. In one case the shells are so numerous that they seem to have formed a sort of burial mantle. "Similarly," says Professor Osborn, describing another of these finds, "the female skeleton was enveloped in a bed of shells not perforated; the legs were extended, while the arms were stretched beside the body; there were a few pierced shells and a few bits of silex. One of the large male skeletons of the same grotto had the lower limbs extended, the upper limbs folded, and was decorated with a gorget and crown of perforated shells; the head rested on a block of red stone." In another case "heavy stones protected the body from disturbance; the head was decorated with a circle of perforated shells coloured in red, and implements of various types were carefully placed on the forehead and chest". The body of the Combe-Capelle man "was decorated with a necklace of perforated shells and surrounded with a great number of fine Aurignacian flints. It appears", adds Osborn, "that in all the numerous burials of these grottos of Aurignacian age and industry of the Crô-Magnon race we have the burial standards which prevailed in western Europe at this time."35

It has been suggested by one of the British archæologists that the necklaces of perforated cowrie shells and the red pigment found among the remains of early man in Britain were used by children. This theory does not accord with the evidence afforded by the Grimaldi caves, in which the infant skeletons are neither coloured nor decorated. Occasionally, however, the children were interred in burial mantles of small perforated shells, while female adults were sometimes placed in beds of unperforated shells. Shells have been found in early British graves. These include Nerita litoralis, and even Patella vulgata, the common limpet. Holes were rubbed in them so that they might be strung together. In a megalithic cist unearthed in Phœnix Park, Dublin, in 1838, two male skeletons had each beside them perforated shells (Nerita litoralis). During the construction of the Edinburgh and Granton railway there was found beside a skeleton in a stone cist a quantity of cockle-shell rings. Two dozen perforated oyster-shells were found in a single Orkney cist. Many other examples of this kind could be referred to.36

In the Crô-Magnon caverns are imprints of human hands which had been laid on rock and then dusted round with coloured earth. In a number of cases it is shown that one or more finger joints of the left hand had been cut off.

The practice of finger mutilation among Bushman, Australian, and Red Indian tribes, is associated with burial customs and the ravages of disease. A Bushman woman may cut off a joint of one of her fingers when a near relative is about to die. Red Indians cut off finger-joints when burying their dead during a pestilence, so as "to cut off deaths"; they sacrificed a part of the body to save the whole. In Australia finger mutilation is occasionally practised. Highland Gaelic stories tell of heroes who lie asleep to gather power which will enable them to combat with monsters or fierce enemies. Heroines awake them by cutting off a finger joint, a part of the ear, or a portion of skin from the scalp.37

The colours used in drawings of hands in Palæolithic caves are black, white, red, and yellow, as the Abbé Breuil has noted. In Spain and India, the hand prints are supposed to protect dwellings from evil influences. Horse-shoes, holly with berries, various plants, shells, &c, are used for a like purpose among those who in our native land perpetuate ancient customs.

The Arabs have a custom of suspending figures of an open hand from the necks of their children, and the Turks and Moors paint hands upon their ships and houses, "as an antidote and counter charm to an evil eye; for five is with them an unlucky number; and 'five (fingers, perhaps) in your eyes' is their proverb of cursing and defiance". In Portugal the hand spell is called the figa. Southey suggests that our common phrase "a fig for him" was derived from the name of the Portuguese hand amulet.38

"The figo for thy friendship" is an interesting reference by Shakespeare.39 Fig or figo is probably from fico, a snap of the fingers, which in French is faire la figue, and in Italian far le fiche. Finger snapping had no doubt originally a magical significance.

CHAPTER V

New Races in Europe

The Solutrean Industry—A Racial and Cultural Intrusion—Decline of Aurignacian Art—A God-cult—The Solutrean Thor—Open-air Life—Magdalenian Culture—Decline of Flint Working—Horn and Bone Weapons and Implements—Revival of Crô-Magnon Art—The Lamps and Palettes of Cave Artists—The Domesticated Horse—Eskimos in Europe—Magdalenian Culture in England—The Vanishing Ice—Reindeer migrate Northward—New Industries—Tardenoisian and Azilian Industries—Pictures and Symbols of Azilians—"Long-heads" and "Broad-heads"—Maglemosian Culture of Fair Northerners—Pre-Neolithic Peoples in Britain.

In late Aurignacian times the influence of a new industry was felt in Western Europe. It first came from the south, and reached as far north as England where it can be traced in the caverns. Then, in time, it spread westward and wedge-like through Central Europe in full strength, with the force and thoroughness of an invasion, reaching the northern fringe of the Spanish coast. This was the Solutrean industry which had distinctive and independent features of its own. It was not derived from Aurignacian but had developed somewhere in Africa—perhaps in Somaliland, whence it radiated along the Libyan coast towards the west and eastward into Asia. The main or "true" Solutrean influence entered Europe from the south-east. It did not pass into Italy, which remained in the Aurignacian stage until Azilian times, nor did it cross the Pyrenees or invade Spain south of the Cantabrian Mountains. The earlier "influence" is referred to as "proto-Solutrean".

Solutrean is well represented in Hungary where no trace of Aurignacian culture has yet been found. Apparently that part of Europe had offered no attractions for the Crô-Magnons.

Who the carriers of this new culture were it is as yet impossible to say with confidence. They may have been a late "wave" of the same people who had first introduced Aurignacian culture into Europe, and they may have been representative of a different race. Some ethnologists incline to connect the Solutrean culture with a new people whose presence is indicated by the skulls found at Brünn and Brüx in Bohemia. These intruders had lower foreheads than the Crô-Magnons, narrower and longer faces, and low cheek-bones. It may be that they represented a variety of the Mediterranean race. Whoever they were, they did not make much use of ivory and bone, but they worked flint with surpassing skill and originality. Their technique was quite distinct from the Aurignacian. With the aid of wooden or bone tools, they finished their flint artifacts by pressure, gave them excellent edges and points, and shaped them with artistic skill. Their most characteristic flints are the so-called laurel-leaf (broad) and willow-leaf (narrow) lances. These were evidently used in the chase. There is no evidence that they were used in battle. Withal, their weapons had a religious significance. Fourteen laurel-leaf spear-heads of Solutrean type which were found together at Volgu, Saône-et-Loire, are believed to have been a votive offering to a deity. At any rate, these were too finely worked and too fragile, like some of the peculiar Shetland and Swedish knives of later times, to have been used as implements. One has retained traces of red colouring. It may be that the belief enshrined in the Gaelic saying, "Every weapon has its demon", had already come into existence. In Crete the double-axe was in Minoan times a symbol of a deity;40 and in northern Egypt and on the Libyan coast the crossed arrows symbolized the goddess Neith; while in various countries, and especially in India, there are ancient stories about the spirits of weapons appearing in visions and promising to aid great hunters and warriors. The custom of giving weapons personal names, which survived for long in Europe, may have had origin in Solutrean times.

Art languished in Solutrean times. Geometrical figures were incised on ivory and bone; some engraving of mammoths, reindeer, and lions have been found in Moravia and France. When the human figure was depicted, the female was neglected and studies made of males. It may be that the Solutreans had a god-cult as distinguished from the goddess-cult of the Aurignacians, and that their "flint-god" was an early form of Zeus, or of Thor, whose earliest hammer was of flint. The Romans revered "Jupiter Lapis" (silex). When the solemn oath was taken at the ceremony of treaty-making, the representative of the Roman people struck a sacrificial pig with the silex and said, "Do thou, Diespiter, strike the Roman people as I strike this pig here to-day, and strike them the more, as thou art greater and stronger". Mr. Cyril Bailey (The Religion of Ancient Rome, p. 7) expresses the view that "in origin the stone is itself the god".

During Solutrean times the climate of Europe, although still cold, was drier that in Aurignacian times. It may be that the intruders seized the flint quarries of the Crô-Magnons, and also disputed with them the possession of hunting-grounds. The cave art declined or was suspended during what may have been a military regime and perhaps, too, under the influence of a new religion and new social customs. Open-air camps beside rock-shelters were greatly favoured. It may be, as has been suggested, that the Solutreans were as expert as the modern Eskimos in providing clothing and skin-tents. Bone needles were numerous. They fed well, and horse-flesh was a specially favoured food.

In their mountain retreats, the Aurignacians may have concentrated more attention than they had previously done on the working of bone and horn; it may be that they were reinforced by new races from north-eastern Europe, who had been developing a distinctive industry on the borders of Asia. At any rate, the industry known as Magdalenian became widespread when the ice-fields crept southward again, and southern and central Europe became as wet and cold as in early Aurignacian times. Solutrean culture gradually declined and vanished and Magdalenian became supreme.

The Magdalenian stage of culture shows affinities with Aurignacian and betrays no influence of Solutrean technique. The method of working flint was quite different. The Magdalenians, indeed, appear to have attached little importance to flint for implements of the chase. They often chipped it badly in their own way and sometimes selected flint of poor quality, but they had beautiful "scrapers" and "gravers" of flint. It does not follow, however, that they were a people on a lower stage of culture than the Solutreans. New inventions had rendered it unnecessary for them to adopt Solutrean technique. Most effective implements of horn and bone had come into use and, if wars were waged—there is no evidence of warfare—the Magdalenians were able to give a good account of themselves with javelins and exceedingly strong spears which were given a greater range by the introduction of spear-throwers—"cases" from which spears were thrown. The food supply was increased by a new method of catching fish. Barbed harpoons of reindeer-horn had been invented, and no doubt many salmon, &c., were caught at river-side stations.

The Crô-Magnons, as has been found, were again in the ascendant, and their artistic genius was given full play as in Aurignacian times, and, no doubt, as a result of the revival of religious beliefs that fostered art as a cult product. Once again the painters, engravers, and sculptors adorned the caves with representations of wild animals. Colours were used with increasing skill and taste. The artists had palettes on which to mix their colours, and used stone lamps, specimens of which have been found, to light up their "studios" in deep cave recesses. During this Magdalenian stage of culture the art of the Crô-Magnons reached its highest standard of excellence, and grew so extraordinarily rich and varied that it compares well with the later religious arts of ancient Egypt and Babylonia.

The horse appears to have been domesticated. There is at Saint Michel d'Arudy a "Celtic" horse depicted with a bridle, while at La Madeleine was found a "bâton de commandement" on which a human figure, with a stave in his right hand, walks past two horses which betray no signs of alarm.

Our knowledge is scanty regarding the races that occupied Europe during Magdalenian times. In addition to the Crô-Magnons there were other distinctive types. One of these is represented by the Chancelade skeleton found at Raymonden shelter. Some think it betrays Eskimo affinities and represents a racial "drift" from the Russian steppes. In his Ancient Hunters Professor Sollas shows that there are resemblances between Eskimo and Magdalenian artifacts.

The Magdalenian culture reached England, although it never penetrated into Italy, and was shut out from the greater part of Spain. It has been traced as far north as Derbyshire, on the north-eastern border of which the Cresswell caves have yielded Magdalenian relics, including flint-borers, engravers, &c., and bone implements, including a needle, an awl, chisels, an engraving of a horse on bone, &c. Kent's Cavern, near Torquay in Devonshire, has also yielded Magdalenian flints and implements of bone, including pins, awls, barbed harpoons, &c.

During early Magdalenian times, however, our native land did not offer great attractions to Continental people. The final glacial epoch may have been partial, but it was severe, and there was a decided lowering of the temperature. Then came a warmer and drier spell, which was followed by the sixth partial glaciation. Thereafter the "great thaw" opened up Europe to the invasion of new races from Asia and Africa.

Three distinct movements of peoples in Europe can be traced in post-Magdalenian times, and during what has been called the "Transition Period", between the Upper Palæolithic and Lower Neolithic Ages or stages. The ice-cap retreated finally from the mountains of Scotland and Sweden, and the reindeer migrated northward. Magdalenian civilization was gradually broken up, and the cave art suffered sharp decline until at length it perished utterly. Trees flourished in areas where formerly the reindeer scraped the snow to crop moss and lichen, and rich pastures attracted the northward migrating red deer, the roe-deer, the ibex, the wild boar, wild cattle, &c.

The new industries are known as the Tardenoisian, the Azilian, and the Maglemosian.

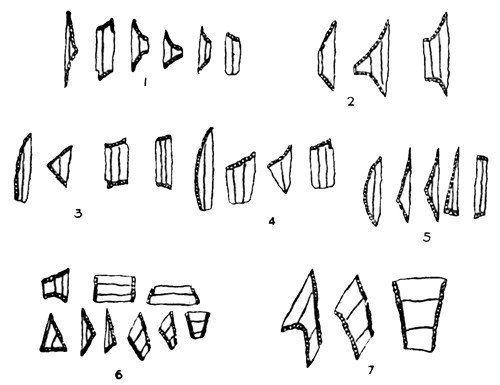

Geometric or "Pygmy" Flints. (After Breuil.)

1, From Tunis and Southern Spain. 2, From Portugal. 3, 4, Azilian types. 5, 6, 7, Tardenoisian types.

Tardenoisian flints are exceedingly small and beautifully worked, and have geometric forms; they are known as "microliths" and "pygmy flints". They were evidently used in catching fish, some being hooks and others spear-heads; and they represent a culture that spread round the Mediterranean basin: these flints are found in northern Egypt, Tunis, Algeria, and Italy; from Italy they passed through Europe into England and Scotland. A people who decorated with scenes of daily life rock shelters and caves in Spain, and hunted red deer and other animals with bows and arrows, were pressing northward across the new grass-lands towards the old Magdalenian stations. Men wore pants and feather head-dresses; women had short gowns, blouses, and caps, as had the late Magdalenians, and both sexes wore armlets, anklets, and other ornaments of magical potency. Females were nude when engaged in the chase. The goddess Diana had evidently her human prototypes. There were ceremonial dances, as the rock pictures show; women lamented over graves, and affectionate couples—at least they seem to have been affectionate—walked hand in hand as they gradually migrated towards northern Spain, and northern France and Britain. The horse was domesticated, and is seen being led by the halter. Wild animal "drives" were organized, and many victims fell to archer and spearman. Arrows were feathered; bows were large and strong. Symbolic signs indicate that a script similar to those of the Ægean area, the northern African coast, and pre-dynastic Egypt was freely used. Drawings became conventional, and ultimately animals and human beings were represented by signs. This culture lasted after the introduction of the Neolithic industry in some areas, and in others after the bronze industry had been adopted by sections of the people.

When the Magdalenian harpoon of reindeer horn was imitated by the flat harpoon of red-deer horn, this new culture became what is known as Azilian. It met and mingled with Tardenoisian, which appears to have arrived later, and the combined industries are referred to as Azilian-Tardenoisian.

While the race-drifts, represented by the carriers of the Azilian and Tardenoisian industries, were moving into France and Britain, another invasion from the East was in progress. It is represented in the famous Ofnet cave where long-heads and broad-heads were interred. The Asiatic Armenoids (Alpine type) had begun to arrive in Europe, the glaciers having vanished in Asia Minor. Skulls of broad-heads found in the Belgian cave of Furfooz, in which sixteen human skeletons were unearthed in 1867, belong to this period. The early Armenoids met and mingled with representatives of the blond northern race, and were the basis of the broad-headed blonds of Holland, Denmark, and Belgium.