полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

That certain of the megalithic monuments were intimately connected with the people who attached a religious value to metals is brought out very forcibly in the references to pagan customs and beliefs in early Christian Gaelic literature. There are statements in the Lives of St. Patrick regarding a pagan god called "Cenn Cruach" and "Crom Cruach" whose stone statue was "adorned with gold and silver, and surrounded by twelve other statues with bronze ornaments". The "statue" is called "the king idol of Erin", and it is stated that "the twelve idols were made of stone, but he ('Crom Cruach') was of gold". To this god of a stone circle were offered up "the firstlings of every issue and the chief scions of every clan". Another idol was called Crom Dubh ("Black Crom"), and his name "is still connected", O'Curry has written, "with the first Sunday of August in Munster and Connaught". An Ulster idol was called Crom Chonnaill, which was either a living animal or a tree, or was "believed to have been such", O'Curry says. De Jubainville translates Cenn Cruach as "Bloody Head" and Crom Cruach as "Bloody Curb" or "Bloody Crescent". O'Curry, on the other hand, translates Crom Cruach as "Bloody Maggot" and Crom Dubh as "Black Maggot". In Gaelic legends "maggots" or "worms" are referred to as forms of supernatural beings. The maggot which appeared on the flesh of a slain animal was apparently regarded as a new form assumed by the indestructible soul, just as in the Egyptian story of Bata the germ of life passes from his bull form in a drop of blood from which two trees spring up, and then in a chip from one of the trees from which the man is restored in his original form.76 A similar belief, which is widespread, is that bees have their origin as maggots placed in trees. One form of the story was taken over by the early Christians, which tells that Jesus was travelling with Peter and Paul and asked hospitality from an old woman. The woman refused it and struck Paul on the head. When the wound putrified maggots were produced. Jesus took the maggots from the wound and placed them in the hollow of a tree. When next they passed that way, "Jesus directed Paul to look in the tree hollow where, to his surprise, he found bees and honey sprung from his own head".77 The custom of placing crape on hives and "telling the bees" when a death takes place, which still survives in the south of England and in the north of Scotland, appears to be connected with the ancient belief that the maggot, bee, and tree were connected with the sacred animal and the sacred stone in which was the spirit of a deity. Sacred trees and sacred stones were intimately connected. Tacitus tells us that the Romans invaded Mona (Anglesea), they destroyed the sacred groves in which the Druids and black-robed priestesses covered the altars with the blood of captives.78 There are a number of dolmens on this island and traces of ancient mine-workings, indicating that it had been occupied by the early seafarers who colonized Britain and Ireland and worked metals. A connection between the tree cult of the Druids and the cult of the builders of megaliths is thus suggested by Tacitus, as well as by the Irish evidence regarding the Ulster idol Crom Chonnaill, referred to above (see also Chapter XII).

Who were the people that followed the earliest Easterners and visited our shores to search like them for metals and erect megalithic monuments? It is impossible to answer that question with certainty. There were after the introduction of bronze working, as has been indicated, intrusions of aliens. These included the introducers of the short-barrow method of burial and the later introducers of burial by cremation. It does not follow that all intrusions were those of conquerors. Traders and artisans may have come with their families in large numbers and mingled with the earlier peoples. Some intruders appear to have come by overland routes from southern and central France and from Central Europe and the Danube valley, while others came across the sea from Spain. That a regular over-seas trade-route was in existence is indicated by the references made by classical writers to the Cassiterides (Tin Islands). Strabo tells that the natives "bartered tin and hides with merchants for pottery, salt, and articles of bronze". The Phœnicians, as has been noted, "monopolized the trade from Gades (Cadiz) with the islanders and kept the route a close secret". It was probably along this sea-route that Egyptian blue beads reached Britain. Professor Sayce has identified a number of these in Devizes Museum, and writes:

"They are met with plentifully in the Early Bronze Age tumuli of Wiltshire in association with amber beads and barrel-shaped beads of jet or lignite. Three of them come from Stonehenge itself. Similar beads of ivory have been found in a Bronze Age cist near Warminster: if the material is really ivory it must have been derived from the East. The cylindrical faience beads, it may be added, have been discovered in Dorsetshire as well as in Wiltshire."

Professor Sayce emphasizes that these blue beads "belong to one particular period in Egyptian history, the latter part of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the earlier part of the Nineteenth Dynasty.... The period to which they belong may be dated 1450-1250 b.c., and as we must allow some time for their passage across the trade routes to Wiltshire an approximate date for their presence in the British barrows will be 1300 b.c."

Beads from Bronze Age Barrows on Salisbury Plain

The large central bead and the small round ones are of amber; the long plain ones are of jet; and the long segmented or notched beads are of an opaque blue substance (faience).

Dr. H. R. Hall, of the British Museum, who discovered, at Deir el-Bahari in Egypt, "thousands of blue glaze beads of the exact particular type of those found in Britain", says that they date back till "about 1500 b.c.". He noted the resemblance before Professor Sayce had written. "It is gratifying", he comments, "that the Professor agrees that the Devizes beads are undoubtedly Egyptian, as an important voice is thereby added to the consensus of opinion on the subject." Similar beads have been found in the "Middle Bronze Age in Crete and in Western Europe". Dr. Hall thinks the Egyptian beads may have reached Britain as early as "about 1400 b.c.".79 We have thus provided for us an early date in British history, based on the well authenticated chronology of the Empire period of Ancient Egypt. Easterners, or traders in touch with Easterners, reached our shores carrying Egyptian beads shortly before or early in the fourteenth century b.c. At this time amber was being imported into the south of England from the Baltic, while jet was being carried from Whitby in Yorkshire.

After the introduction of bronze working in Western Europe the natives began to work and use metals. These could not have been Celts, for in the fourteenth century b.c. the Celts had not yet reached Western Europe.80 The earliest searchers for metals who visited Britain must therefore have been the congeners of those who erected the megalithic monuments in the metal-yielding areas of Spain and Portugal and north-western France.

It would appear that the early Easterners exploited the virgin riches of Western Europe for a long period—perhaps for over a thousand years—and that, after their Spanish colonies were broken up by a bronze-using people from Central Europe, the knowledge of how to work metals spread among the natives. Overland trade routes were then opened up. At first these were controlled in Western Europe by the Iberians. In time the Celts swept westward and formed with the natives mixed communities of Celtiberians. The Easterners appear to have inaugurated a new era in Western European commerce after the introduction of iron working. They had colonies in the south and west of Europe and on the North African coast, and obtained supplies of metals, &c., by sea. They kept the sea-routes secret. British ores, &c., were carried to Spain and Carthage. After Pytheas visited Britain (see next chapter) the overland trade-route to Marseilles was opened up. Supplies of surface tin having become exhausted, tin-mines were opened in Cornwall. The trade of Britain then came under the control of Celtiberian and Celtic peoples, who had acquired their knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation from the Easterners and the mixed descendants of Eastern and Iberian peoples.

It does not follow that the early and later Easterners were all of one physical type. They, no doubt, brought with them their slaves, including miners and seamen, drawn from various countries where they had been purchased or abducted.

The men who controlled the ancient trade were not necessarily permanent settlers in Western Europe. When the carriers of bronze from Central Europe obtained control of the Iberian colonies, many traders may have fled to other countries, but many colonists, and especially the workers, may have become the slaves of the intruders, as did the Fir-bolgs of Ireland who were subdued by the Celts. The Damnonians of Britain and Ireland who occupied mineral areas may have been a "wave" of early Celtic or Celtiberian people. Ultimately the Celts came, as did the later Normans, and formed military aristocracies over peoples of mixed descent. The idea that each intrusion involved the extermination of earlier peoples is a theory which does not accord with the evidence of the ancient Gaelic manuscripts, of classical writers, of folk tradition, and of existing race types in different areas in Britain and Ireland.

A people who exterminated those they conquered would have robbed themselves of the chief fruits of conquest. In ancient as in later times the aim of conquest was to obtain the services of a subject people and the control of trade.

CHAPTER X

Celts and Iberians as Intruders and Traders

Few Invasions in 1000 Years—Broad-heads—The Cremating People—A New Religion—Celtic People in Britain—The Continental Celts—Were Celts Dark or Fair?—Fair Types in Britain and Ireland—Celts as Pork Traders—The Ancient Tin Trade—Early Explorers—Pytheas and Himilco—The Cassiterides—Tin Mines and Surface Tin—Cornish Tin—Metals in Hebrides and Ireland—Lead in Orkney—Dark People in Hebrides and Orkney—Celtic Art—Homeric Civilization in Britain and Ireland—Why Romans were Conquerors.

The beginnings of the Bronze and Iron Ages in Britain are, according to the chronology favoured by archæologists, separated by about a thousand years. During this long period only two or three invasions appear to have taken place, but it is uncertain, as has been indicated, whether these came as sudden outbursts from the Continent or were simply gradual and peaceful infiltrations of traders and settlers. We really know nothing about the broad-headed people who introduced the round-barrow system of burial, or of the people who cremated their dead. The latter became predominant in south-western England and part of Wales. In the north of England the cremating people were less numerous. If they were conquerors they may have, as has been suggested, represented military aristocracies. It may be, however, on the other hand, that the cremation custom had in some areas more a religious than a racial significance. The beliefs associated with cremation of the dead may have spread farther than the people who introduced the new religion. It would appear that the habit of burning the dead was an expression of the beliefs that souls were transported by means of fire to the Otherworld paradise. As much is indicated by Greek evidence. Homer's heroes burned their dead, and when the ghost of Patroklos appeared to his friend Achilles in a dream, he said: "Thou sleepest, and hast forgotten me, O Achilles. Not in my life wast thou unmindful of me, but in my death. Bury me with all speed, that I may pass the gates of Hades. Far off the spirits banish me, the phantoms of men outworn, nor suffer me to mingle with them beyond the River, but vainly I wander along the wide-gated dwelling of Hades. Now give me, I pray pitifully of thee, thy hand, for never more again shall I come back from Hades, when ye have given me my due of fire."81 The Arab traveller Ibn Haukal, who describes a tenth-century cremation ceremony at Kieff, was addressed by a Russ, who said: "As for you Arabs you are mad, for those who are the most dear to you, and whom you honour most, you place in the ground, where they will become a prey to worms, whereas with us they are burned in an instant and go straight to Paradise."82

The cremating people, who swept into Greece and became the over-lords of the earlier settlers, were represented in the western movement of tribes towards Gaul and Britain. It is uncertain where the cremation custom had origin. Apparently it entered Europe from Asia. The Vedic Aryans who invaded Northern India worshipped the fire-god Agni, who was believed to carry souls to Paradise; they cremated their dead and combined with it the practice of suttee, that is, of burning the widows of the dead. In Gaul, however, as we gather from Julius Cæsar, only those widows suspected of being concerned in the death of their husbands were burned. The Norsemen, however, were acquainted with suttee. In one of the Volsung lays Brynhild rides towards the pyre on which Sigurd is being burned, and casts herself into the flames. The Russians strangled and burned widows when great men were cremated.

The cremating people erected megalithic monuments, some of which cover their graves in Britain and elsewhere.

In some districts the intruders of the Bronze Age were the earliest settlers. The evidence of the graves in Buchan, Aberdeenshire, for instance, shows that the broad-heads colonized that area. It may be that, like the later Norsemen, bands of people sought for new homes in countries where the struggle for existence would be less arduous than in their own, which suffered from over population, and did not land at points where resistance was offered to them. Agriculturists would, no doubt, select areas suitable for their mode of life and favour river valleys, while seafarers and fishermen would cling to the coasts. The tendency of fishermen and agriculturists to live apart in separate communities has persisted till our own time. There are fishing villages along the east coast of Scotland the inhabitants of which rarely intermarry with those who draw their means of sustenance from the land.

During the Bronze Age Celtic peoples were filtering into Britain from Gaul. They appear to have come originally from the Danube area as conquerors who imposed their rule on the people they subjected. Like the Achæans who overran Greece they seem to have originally been a vigorous pastoral people who had herds of pigs, were "horse-tamers", used chariots, and were fierce and impetuous in battle. In time they crossed the Rhine and occupied Gaul. They overcame the Etruscans. In 390 b.c. they sacked Rome. Their invasion of Greece occurred in the third century, but their attempt to reach Delphi was frustrated. Crossing into Asia Minor they secured a footing in the area subsequently known as Galatia, and their descendants there were addressed in an epistle by St. Paul.

Like the Achæans, the Celts appear to have absorbed the culture of the Ægean area and that of the Ægean colony at Hallstatt in Austria. They were withal the "carriers" of the La Tène Iron Age culture to Britain and Ireland. The potter's wheel was introduced by them into Britain during the archæological early Iron Age. It is possible that the cremating people of the Bronze Age were a Celtic people. But later "waves" of the fighting charioteers did not cremate their dead.

Sharp difference of opinion exists between scholars regarding the Celts. Some identify them with the dark-haired, broad-headed Armenoids, and others with the tall and fair long-headed people of Northern Europe. It is possible that the Celts were not a pure race, but rather a confederacy of peoples who were influenced at different periods by different cultures. That some sections were confederacies or small nations of blended people is made evident by classic references to the Celtiberians, the Celto-Scythians, the Celto-Ligyes, the Celto-Thracians, and the Celtillyrians. On reaching Britain they mingled with the earlier settlers, forming military aristocracies, and dominating large areas. The fair Caledonians of Scotland had a Celtic tribal name, and used chariots in battle like the Continental Celts. Two Caledonian personal names are known—Calgacus ("swordsman") and Argentocoxus ("white foot"). In Ireland the predominant tribes before and during the early Roman period were of similar type. Queen Meave of Connaught was like Queen Boadicea83 of the Iceni, a fair-haired woman who rode to battle in a chariot.

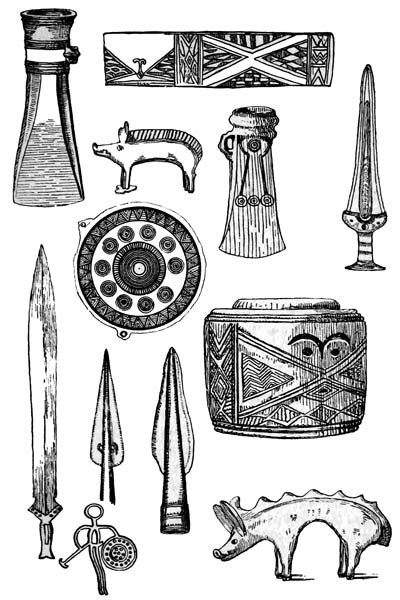

Weapons and Religious Objects (British Museum)

Bronze socketed celts, bronze dagger, sword and spear-heads from Thames; two bronze boars with "sun-disc" ears, which were worn on armour; bronze "sun-disc" from Ireland; "chalk drum" from grave (Yorkshire), with ornamentation showing butterfly and St. Andrew's Cross symbols; warrior with shield, from rock carving (Denmark).

The Continental trade routes up the Danube and Rhone valleys leading towards Britain were for some centuries under the control of the Celts. It was no doubt to obtain a control over trade that they entered Britain and Ireland. On the Continent they engaged in pork curing, and supplied Rome and indeed the whole of Italy with smoked and salted bacon. Dr. Sullivan tells that among the ancient Irish the general name for bacon was tini. Smoke-cured hams and flitches were called tineiccas, which "is almost identical in form with the Gallo-Roman word taniaccae or tanacae used by Varro for hams imported from Transalpine Gaul into Rome and other parts of Italy". Puddings prepared from the blood of pigs—now known as "black puddings"—were, we learn from Varro, likewise exported from Gaul to Italy. The ancient Irish were partial to "black puddings".84 It would appear, therefore, that the so-called dreamy Celt was a greasy pork merchant.

According to Strabo the exports from Britain in the early part of the first century consisted of gold, silver, and iron, wheat, cattle, skins, slaves, and dogs; while the imports included ivory ornaments, such as bracelets, amber beads, and glass. Tin was exported from Cornwall to Gaul, and carried overland to Marseilles, but this does not appear to have been the earliest route. As has been indicated, tin appears to have been carried, before the Celts obtained control of British trade, by the sea route to the Carthaginian colonies in Spain.

The Carthaginians had long kept secret the sources of their supplies of tin from the group of islands known as the Cassiterides. About 322 b.c., however, the Greek merchants at Marseilles fitted out an expedition which was placed in charge of Pytheas, a mathematician, for the purpose of exploring the northern area. This scholar wrote an account of his voyage, but only fragments of it quoted by different ancient authors have come down to us. He appears to have coasted round Spain and Brittany, and to have sailed up the English Channel to Kent, to have reached as far north as Orkney and Shetland, and perhaps, as some think, Iceland, to have crossed the North Sea towards the mouth of the Baltic, and explored a part of the coast of Norway. He returned to Britain, which he appears to have partly explored before crossing over to Gaul. In an extract from his diary, quoted by Strabo, he tells that the Britons in certain districts not detailed grew corn, millet, and vegetables. Such of them as had corn and honey made a beverage from these materials. They brought the corn ears into great houses (barns) and threshed them there, for on account of the rain and lack of sunshine out-door threshing floors were of little use to them. Pytheas noted that in Britain the days were longer and the nights brighter than in the Mediterranean area. In the northern parts he visited the nights were so short that the interval between sunset and sunrise was scarcely perceptible. The farthest north headland of Britain was Cape Orcas.85 Six days sail north of Britain lay Thule, which was situated near the frozen sea. There a day lasted six months and a night for the same space of time.

Another extract refers to hot springs in Britain, and a presiding deity identified with Minerva, in whose temple "the fires never go out, yet never whiten into ashes; when the fire has got dull it turns into round lumps like stones". Apparently coal was in use at a temple situated at Bath. Timæus, a contemporary of Pytheas, quoting from the lost diary of the explorer, states that tin was found on an island called Mictis, lying inwards (northward) at a distance of six days' sail from Britain. The natives made voyages to and from the island in their canoes of wickerwork covered with hides. Mictis could not have been Cornwall or an island in the English Channel. Strabo states that Crassus, who succeeded in reaching the Cassiterides, announced that the distance to them was greater than that from the Continent to Britain, and he found that the tin ore lay on the surface. Evidently tin was not mined on the island of Mictis as it was in Cornwall in later times.

An earlier explorer than Pytheas was Himilco, the Carthaginian. He reached Britain about 500 b.c. A Latin metrical rendering of his lost work was made by Rufus Festus Avienus in the fourth century of our era. Reference is made to the islands called the Œstrymnides that "raise their heads, lie scattered, and are rich in tin and lead". These islands were visited by Himilco, and were distant "two days voyage from the Sacred Island (Ireland) and near the broad Isle of the Albiones". As Rufus Festus Avienus refers to "the hardy folk of Britain", his Albiones may have been the people of Scotland. The name Albion was originally applied to England and Scotland. In the first century, however, Latin writers never used "Albion" except as a curiosity, and knew England as Britain. According to Himilco, the Tartessi of Spain were wont to trade with the natives of the northern tin islands. Even the Carthaginians "were accustomed to visit these seas". From other sources we learn that the Phœnicians carried tin from the Cassiterides direct to the Spanish port of Corbilo, the exact location of which is uncertain.

ENAMELLED BRONZE SHIELD (from the Thames near Battersea)

(British Museum)

It is of special importance to note that the tin-stone was collected on the surface of the islands before mining operations were conducted elsewhere. In all probability the laborious work of digging mines was not commenced before the available surface supplies became scanty. According to Sir John Rhys86 the districts in southern England, where surface tin was first obtained, were "chiefly Dartmoor, with the country round Tavistock and that around St. Austell, including several valleys looking towards the southern coast of Cornwall. In most of the old districts where tin existed, it is supposed to have lain too deep to have been worked in early times." When, however, Poseidonius visited Cornwall in the first century of our era, he found that a beginning had been made in skilful mining operations. It may be that the trade with the Cassiterides was already languishing on account of changed political conditions and the shortage of supplies.

Where then were the Cassiterides? M. Reinach struck at the heart of the problem when he asked, "In what western European island is tin found?" Those writers who have favoured the group of islands off the north-western coast of Spain are confronted by the difficulty that these have failed to yield traces of tin, while those writers who favour Cornwall and the Scilly Islands cannot ignore the precise statements that the "tin islands" were farther distant from the Continent than Britain, and that in the time of Pytheas tin was carried from Mictis, which was six days' sail from Britain. The fact that traces of tin, copper, and lead have been found in the Hebrides is therefore of special interest. Copper, too, has been found in Shetland, and lead and zinc in Orkney. Withal there are Gaelic place-names in which staoin (tin) is referred to, in Islay, Jura (where there are traces of old mine-workings), in Iona, and on the mainland of Ross-shire. Traces of tin are said to have been found in Lewis where the great stone circle of Callernish in a semi-barren area indicates the presence at one time in its area of a considerable population. The Hebrides may well have been the Œstrymnides of Himilco and the Cassiterides of classical writers. Jura or Iona may have been the Mictis of Pytheas. Tin-stone has been found in Ireland too, near Dublin, in Wicklow, and in Killarney.