полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

The Piltdown skull appears to date back to a period vastly more ancient than Neanderthal times.

Our special interest in the story of early man in Britain is with the "Red Man" of Paviland and Galley Hill man, because these were representatives of the species to which we ourselves belong. The Neanderthals and pre-Neanderthals, who have left their Eoliths and Palæoliths in our gravels, vanished like the glaciers and the icebergs, and have left, as has been indicated, no descendants in our midst. Our history begins with the arrival of the Crô-Magnon races, who were followed in time by other peoples to whom Europe offered attractions during the period of the great thaw, when the ice-cap was shrinking towards the north, and the flooded rivers were forming the beds on which they now flow.

We have little to learn from Galley Hill man. His geological horizon is uncertain, but the balance of the available evidence tends to show he was a pioneer of the medium-sized hunters who entered Europe from the east, during the Aurignacian stage of culture. It is otherwise with the "Red Man" of Wales. We know definitely what particular family he belonged to; he was a representative of the tall variety of Crô-Magnons. We know too that those who loved him, and laid his lifeless body in the Paviland Cave, had introduced into Europe the germs of a culture that had been radiated from some centre, probably in the ancient forest land to the east of the Nile, along the North African coast at a time when it jutted far out into the Mediterranean and the Sahara was a grassy plain.

The Crô-Magnons were no mere savages who lived the life of animals and concerned themselves merely with their material needs. They appear to have been a people of active, inventive, and inquiring minds, with a social organization and a body of definite beliefs, which found expression in their art and in their burial customs. The "Red Man" was so called by the archæologists because his bones and the earth beside them were stained, as has been noted, by "red micaceous oxide of iron". Here we meet with an ancient custom of high significance. It was not the case, as some have suggested, that the skeleton was coloured after the flesh had decayed. There was no indication when the human remains were discovered that the grave had been disturbed after the corpse was laid in it. The fact that the earth as well as the bones retained the coloration affords clear proof that the corpse had been smeared over with red earth which, after the flesh had decayed, fell on the skeleton and the earth and gravel beside it. But why, it will be asked, was the corpse so treated? Did the Crô-Magnons paint their bodies during life, as do the Australians, the Red Indians, and others, to provide "a substitute for clothing"? That cannot be the reason. They could not have concerned themselves about a "substitute" for something they did not possess. In France, the Crô-Magnons have left pictorial records of their activities and interests in their caves and other shelters. Bas reliefs on boulders within a shelter at Laussel show that they did not wear clothing during the Aurignacian epoch which continued for many long centuries. We know too that the Australians and Indians painted their bodies for religious and magical purposes—to protect themselves in battle or enable them to perform their mysteries—rain-getting, food-getting, and other ceremonies. The ancient Egyptians painted their gods to "make them healthy". Prolonged good health was immortality.

The evidence afforded by the Paviland and other Crô-Magnon burials indicates that the red colour was freshly applied before the dead was laid in the sepulchre. No doubt it was intended to serve a definite purpose, that it was an expression of a system of beliefs regarding life and the hereafter.

Apparently among the Crô-Magnons the belief was already prevalent that the "blood is the life". The loss of life appeared to them to be due to the loss of the red vitalizing fluid which flowed in the veins. Strong men who received wounds in conflict with their fellows, or with wild animals, were seen to faint and die in consequence of profuse bleeding; and those who were stricken with sickness grew ashen pale because, as it seemed, the supply of blood was insufficient, a condition they may have accounted for, as did the Babylonians of a later period, by conceiving that demons entered the body and devoured the flesh and blood. It is not too much to suppose that they feared death, and that like other Pagan religions of antiquity theirs was deeply concerned with the problem of how to restore and prolong life. Their medicine-men appear to have arrived at the conclusion that the active principle in blood was the substance that coloured it, and they identified this substance with red earth. If cheeks grew pale in sickness, the flush of health seemed to be restored by the application of a red face paint. The patient did not invariably regain strength, but when he did, the recovery was in all likelihood attributed to the influence of the blood substitute. Rest and slumber were required, as experience showed, to work the cure. When death took place, it seemed to be a deeper and more prolonged slumber, and the whole body was smeared over with the vitalizing blood substitute so that, when the spell of weakness had passed away, the sleeper might awaken, and come forth again with renewed strength from the cave-house in which he had been laid.

The many persistent legends about famous "sleepers" that survive till our own day appear to have originally been connected with a belief in the return of the dead, the antiquity of which we are not justified in limiting, especially when it is found that the beliefs connected with body paint and shell ornaments and amulets were introduced into Europe in early post-glacial times. Ancient folk heroes might be forgotten, but from Age to Age there arose new heroes to take their places; the habit of placing them among the sleepers remained. Charlemagne, Frederick of Barbarossa, William Tell, King Arthur, the Fians, and the Irish Brian Boroimhe, are famous sleepers. French peasants long believed that the sleeping Napoleon would one day return to protect their native land from invaders, and during the Russo-Japanese war it was whispered in Russia that General Skobeleff would suddenly awake and hasten to Manchuria to lead their troops to victory. For many generations the Scots were convinced that James IV, who fell at Flodden, was a "sleeper". His place was taken in time by Thomas the Rhymer, who slept in a cave and occasionally awoke to visit markets so that he might purchase horses for the great war which was to redden Tweed and Clyde with blood. Even in our own day there were those who refused to believe that General Gordon, Sir Hector MacDonald, and Lord Kitchener, were really dead. The haunting belief in sleeping heroes dies hard.

Among the famous groups of sleeping heroes are the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus—the Christians who had been condemned to death by the Emperor Decius and concealed themselves in a cave where they slept for three and a half centuries. An eighteenth century legend tells of seven men in Roman attire, who lay in a cave in Western Germany. In Norse Mythology, the seven sons of Mimer sleep in the Underworld awaiting the blast of the horn, which will be blown at Ragnarok when the gods and demons will wage the last battle. The sleepers of Arabia once awoke to foretell the coming of Mahomet, and their sleeping dog, according to Moslem beliefs, is one of the ten animals that will enter Paradise.

A representative Scottish legend regarding the sleepers is located at the Cave of Craigiehowe in the Black Isle, Ross-shire, a few miles distant from the Rosemarkie cave. It is told that a shepherd once entered the cave and saw the sleepers and their dog. A horn, or as some say, a whistle, hung suspended from the roof. The shepherd blew it once and the sleepers shook themselves; he blew a second time, and they opened their eyes and raised themselves on their elbows. Terrified by the forbidding aspect of the mighty men, the shepherd refrained from blowing a third time, but turned and fled. As he left the cave he heard one of the heroes call after him: "Alas! you have left us worse than you found us." As whistles are sometimes found in Magdalenian shelters in Western and Central Europe, it may be that these were at an early period connected with the beliefs about the calling back of the Crô-Magnon dead. The ancient whistles were made of hare—and reindeer-foot bone. The clay whistle dates from the introduction of the Neolithic industry in Hungary.

The remarkable tendency on the part of mankind to cling to and perpetuate ancient beliefs and customs, and especially those connected with sickness and death, is forcibly illustrated by the custom of smearing the bodies of the living and dead with red ochre. In every part of the world red is regarded as a particularly "lucky colour", which protects houses and human beings, and imparts vitality to those who use it. The belief in the protective value of red berries is perpetuated in our own Christmas customs when houses are decorated with holly, and by those dwellers in remote parts who still tie rowan berries to their cows' tails so as to prevent witches and fairies from interfering with the milk supply. Egyptian women who wore a red jasper in their waist-girdles called the stone "a drop of the blood of Isis (the mother goddess)".

Red symbolism is everywhere connected with lifeblood and the "vital spark"—the hot "blood of life". Brinton15 has shown that in the North American languages the word for blood is derived from the word for red or the word for fire. The ancient Greek custom of painting red the wooden images of gods was evidently connected with the belief that a supply of lifeblood was thus assured, and that the colour animated the Deity, as Homer's ghosts were animated by a blood offering when Odysseus visited Hades. "The anointing of idols with blood for the purpose of animating them is", says Farnell, "a part of old Mediterranean magic."16 The ancient Egyptians, as has been indicated, painted their gods, some of whom wore red garments; a part of their underworld Dewat was "Red Land", and there were "red souls" in it.17 In India standing stones connected with deities are either painted red or smeared with the blood of a sacrificed animal. The Chinese regard red as the colour of fire and light, and in their philosophy they identify it with Yang, the chief principle of life;18 it is believed "to expel pernicious influences, and thus particularly to symbolize good luck, happiness, delight, and pleasure". Red coffins are favoured. The "red gate" on the south side of a cemetery "is never opened except for the passage of an Emperor".19 The Chinese put a powdered red stone called hun-hong in a drink or in food to destroy an evil spirit which may have taken possession of one. Red earth is eaten for a similar reason by the Polynesians and others. Many instances of this kind could be given to illustrate the widespread persistence of the belief in the vitalizing and protective qualities associated with red substances. In Irish Gaelic, Professor W. J. Watson tells me, "ruadh" means both "red" and "strong".

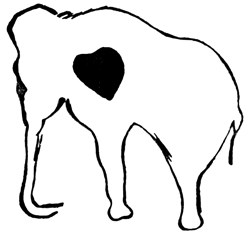

The Crô-Magnons regarded the heart as the seat of life, having apparently discovered that it controls the distribution of blood. In the cavern of Pindal, in south-western France, is the outline of a hairy mammoth painted in red ochre, and the seat of life is indicated by a large red heart. The painting dates back to the early Aurignacian period. In other cases, as in the drawing of a large bison in the cavern of Niaux, the seat of life and the vulnerable parts are indicated by spear—or arrowheads incised on the body. The ancient Egyptians identified the heart with the mind. To them the heart was the seat of intelligence and will-power as well as the seat of life. The germ of this belief can apparently be found in the pictorial art and burial customs of the Aurignacian Crô-Magnons.

Outline of a Mammoth painted in red ochre in the Cavern of Pindal, France

The seat of life is indicated by a large red heart. (After Breuil.)

Another interesting burial custom has been traced in the Grimaldi caves. Some of the skeletons were found to have small green stones between their teeth or inside their mouths.20 No doubt these were amulets. Their colour suggests that green symbolism has not necessarily a connection with agricultural religion, as some have supposed. The Crô-Magnons do not appear to have paid much attention to vegetation. In ancient Egypt the green stone (Khepera) amulet "typified the germ of life". A text says, "A scarab of green stone … shall be placed in the heart of a man, and it shall perform for him the 'opening of the mouth'"—that is, it will enable him to speak and eat again. The scarab is addressed in a funerary text, "My heart, my mother. My heart whereby I came into being." It is believed by Budge that the Egyptian custom of "burying green basalt scarabs inside or on the breasts of the dead" is as old as the first Dynasty (c. 3400 b.c.).21 How much older it is one can only speculate. "The Mexicans", according to Brinton, "were accustomed to say that at one time all men have been stones, and that at last they would all return to stones, and acting literally on this conviction they interred with the bones of the dead a small green stone, which was called 'the principle of life'."22 In China the custom of placing jade tongue amulets for the purpose of preserving the dead from decay and stimulating the soul to take flight to Paradise is of considerable antiquity.23 Crystals and pebbles have been found in ancient British graves. It may well be that these pebbles were regarded as having had an intimate connection with deities, and perhaps to have been coagulated forms of what has been called "life substance". Of undoubted importance and significance was the ancient custom of adorning the dead with shells. As we have seen, this was a notable feature of the Paviland cave burial. The "Red Man" was not only smeared with red earth, but "charmed" or protected by shell amulets. In the next chapter it will be shown that this custom not only affords us a glimpse of Aurignacian religious beliefs, but indicates the area from which the Crô-Magnons came.

Professor G. Elliot Smith was the first to emphasize the importance attached in ancient times to the beliefs associated with the divine "giver of life".

CHAPTER IV

Shell Deities and Early Trade

Early Culture and Early Races—Did Civilization originate in Europe?—An Important Clue—Trade in Shells between Red Sea and Italy—Traces of Early Trade in Central Europe—Religious Value of Personal Ornaments—Importance of Shell Lore—Links between Far East and Europe—Shell Deities—A Hebridean Shell Goddess—"Milk of Wisdom"—Ancient Goddesses as Providers of Food—Gaelic "Spirit Shell" and Japanese "God Body"—Influence of Deities in Jewels, &c.—A Shakespearean Reference—Shells in Crô-Magnon Graves—Early Sacrifices—Hand Colours in Palæolithic Caves—Finger Lore and "Hand Spells".

When the question is asked, "Whence came the Crô-Magnon people of the Aurignacian phase of culture?" the answer usually given is, "Somewhere in the East". The distribution of the Aurignacian sites indicates that the new-comers entered south-western France by way of Italy—that is, across the Italian land-bridge from North Africa. Of special significance in this connection is the fact that Aurignacian culture persisted for the longest period of time in Italy. The tallest Crô-Magnons appear to have inhabited south-eastern France and the western shores of Italy. "It is probable", says Osborn, referring to the men six feet four and a half inches in height, "that in the genial climate of the Riviera these men obtained their finest development; the country was admirably protected from the cold winds of the north, refuges were abundant, and game by no means scarce, to judge from the quantity of animal bones found in the caves. Under such conditions of life the race enjoyed a fine physical development and dispersed widely."24

It does not follow, however, that the tall people originated Aurignacian culture. As has been indicated, the stumpy people represented by Combe-Capelle skeletons were likewise exponents of it. "It must not be assumed", as Elliot Smith reminds us, "that the Aurignacian culture was necessarily invented by the same people who introduced it into Europe, and whose remains were associated with it … for any culture can be transmitted to an alien people, even when it has not been adopted by many branches of the race which was responsible for its invention, just as gas illumination, oil lamps, and even candles are still in current use by the people who invented the electric light, which has been widely adopted by many foreign peoples. This elementary consideration is so often ignored that it is necessary thus to emphasize it, because it is essential for any proper understanding of the history of early civilization."25

No trace of Aurignacian culture has, so far, been found outside Europe. "May it not, therefore," it may be asked, "have originated in Italy or France?" In absence of direct evidence, this possibility might be admitted. But an important discovery has been made at Grimaldi in La Grotte des Enfants (the "grotto of infants"—so called because of the discovery there of the skeletons of young Crô-Magnon children). Among the shells used as amulets by those who used the grotto as a sepulchre was one (Cassis rufa) that had been carried either by a migrating folk, or by traders, along the North African coast and through Italy from some south-western Asian beach. The find has been recorded by Professor Marcellin Boule.26

In a footnote, G. Dollfus writes:

"Cassis rufa, L., an Indian ocean shell, is represented in the collection at Monaco by two fragments; one was found in the lower habitation level D, the other is probably of the same origin. The presence of this shell is extraordinary, as it has no analogue in the Mediterranean, neither recent nor fossil; there exists no species in the North Atlantic or off Senegal with which it could be confounded. The fragments have traces of the reddish colour preserved, and are not fossil; one of them presents a notch which has determined a hole that seems to have been made intentionally. The species has not yet been found in the Gulf of Suez nor in the raised beaches of the Isthmus. M. Jousseaume has found it in the Gulf of Tadjoura at Aden, but it has not yet been encountered in the Red Sea nor in the raised beaches of that region. The common habitat of Cassis rufa is Socotra, besides the Seychelles, Madagascar, Mauritius, New Caledonia, and perhaps Tahiti. The fragments discovered at Mentone have therefore been brought from a great distance at a very ancient epoch by prehistoric man."

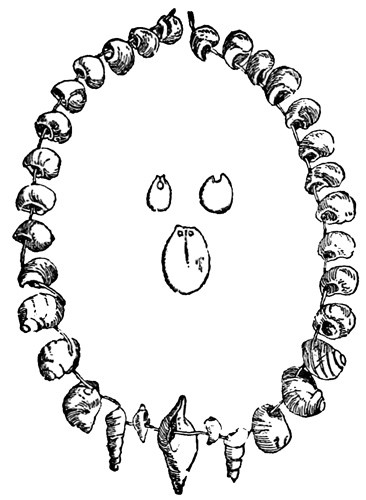

After the Crô-Magnon peoples had spread into Western and Central Europe they imported shells from the Mediterranean. At Laugerie Basse in the Dordogne, for instance, a necklace of pierced shells from the Mediterranean was found in association with a skeleton. Atlantic shells could have been obtained from a nearer sea-shore. It may be that the Rhone valley, which later became a well-known trade route, was utilized at an exceedingly remote period, and that cultural influences occasionally "flowed" along it. "Prehistoric man" had acquired some experience as a trader even during the "hunting period", and he had formulated definite religious beliefs.

It has been the habit of some archæologists to refer to shell and other necklaces, &c., as "personal ornaments". The late Dr. Robert Munro wrote in this connection:

"We have no knowledge of any phase of humanity in which the love of personal ornament does not play an important part in the life of the individual. The savage of the present day, who paints or tattoos his body, and adorns it with shells, feathers, teeth, and trinkets made of the more gaudy materials at his disposal, may be accepted as on a parallel with the Neolithic people of Europe.... Teeth are often perforated and used as pendants, especially the canines of carnivorous animals, but such ornaments are not peculiar to Neolithic times, as they were equally prevalent among the later Palæolithic races of Europe."27

Modern savages have very definite reasons for wearing the so-called "ornaments", and for painting and tattooing their bodies. They believe that the shells, teeth, &c., afford them protection, and bring them luck. Earpiercing, distending the lobe of the ear, disfiguring the body, the pointing, blackening, or knocking out of teeth, are all practices that have a religious significance. Even such a highly civilized people as the Chinese perpetuate, in their funerary ceremonies, customs that can be traced back to an exceedingly remote period in the history of mankind. It is not due to "love of personal ornament" that they place cowries, jade, gold, &c., in the mouth of the dead, but because they believe that by so doing the body is protected, and given a new lease of life. The Far Eastern belief that an elixir of ground oyster shells will prolong life in the next world is evidently a relic of early shell lore. Certain deities are associated with certain shells. Some deities have, like snails, shells for "houses"; others issue at birth from shells. The goddess Venus (Aphrodite) springs from the froth of the sea, and is lifted up by Tritons on a shell; she wears a love-girdle. Hathor, the Egyptian Venus, had originally a love-girdle of shells. She appears to have originated as the personification of a shell, and afterwards to have personified the pearl within the shell. In early Egyptian graves the shell-amulets have been found in thousands. The importance of shell lore in ancient religious systems has been emphasized by Mr. J. Wilfrid Jackson in his Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture.28 He shows why the cowry and snail shells were worn as amulets and charms, and why men were impelled "to search for them far and wide and often at great peril". "The murmur of the shell was the voice of the god, and the trumpet made of a shell became an important instrument in initiation ceremonies and in temple worship." Shells protected wearers against evil, including the evil eye. In like manner protection was afforded by the teeth and claws of carnivorous animals. In Asia and Africa the belief that tigers, lions, &c., will not injure those who are thus protected is still quite widespread.

Necklace of Sea Shells, from the cave of Crô-Magnon. (After E. Lartet.)

It cannot have been merely for love of personal ornaments that the Crô-Magnons of southern France imported Indian Ocean shells, and those of Central and Western Europe created a trade in Mediterranean shells. Like the ancient inhabitants of the Nile Valley who in remote pre-dynastic times imported shells, not only from the Mediterranean but from the Red Sea, along a long and dangerous desert trade-route, they evidently had imparted to shells a definite religious significance. The "luck-girdle" of snail-shells worn by the "Red Man of Paviland" has, therefore, an interesting history. When the Crô-Magnons reached Britain they brought with them not only implements invented and developed elsewhere, but a heritage of religious beliefs connected with shell ornaments and with the red earth with which the corpse was smeared when laid in its last resting-place.

The ancient religious beliefs connected with shells appear to have spread far and wide. Traces of them still survive in districts far separated from one another and from the area of origin—the borderlands of Asia and Africa. In Japanese mythology a young god, Ohonamochie—a sort of male Cinderella—is slain by his jealous brothers. His mother makes appeal to a sky deity who sends to her aid the two goddesses Princess Cockleshell and Princess Clam. Princess Cockleshell burns and grinds her shell, and with water provided by Princess Clam prepares an elixir called "nurse's milk" or "mother's milk". As soon as this "milk" is smeared over the young god, he is restored to life. In the Hebrides it is still the custom of mothers to burn and grind the cockle-shell to prepare a lime-water for children who suffer from what in Gaelic is called "wasting". In North America shells of Unio were placed in the graves of Red Indians "as food for the dead during the journey to the land of spirits". The pearls were used in India as medicines. "The burnt powder of the gems, if taken with water, cures hæmorrhages, prevents evil spirits working mischief in men's minds, cures lunacy and all mental diseases, jaundice, &c.... Rubbed over the body with other medicines it cures leprosy and all skin diseases."29 The ancient Cretans, whose culture was carried into Asia and through Europe by their enterprising sea-and-land traders and prospectors, attached great importance to the cockle-shell which they connected with their mother goddess, the source of all life and the giver of medicines and food. Sir Arthur Evans found a large number of cockle-shells, some in Faeince, in the shrine of the serpent goddess in the ruins of the Palace of Knossos. The fact that the Cretans made artificial cockle-shells is of special interest, especially when we find that in Egypt the earliest use to which gold was put was in the manufacture of models of snail-shells in a necklace.30 In different countries cowrie shells were similarly imitated in stone, ivory, and metal.31