полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

Thus far the street and its idleness as factors in making criminals of the boys. Of the factory I have spoken. Certainly it is to be preferred to the street, if the choice must be between the two. Its offence is that it makes a liar of the boy and keeps him in ignorance, even of a useful trade, thus blazing a wide path for him straight to the prison gate. The school does not come to the rescue; the child must come to the school, and even then is not sure of a welcome. The trades’ unions do their worst for the boy by robbing him of the slim chance to learn a trade which the factory left him. Of the tenement I have said enough. Apart from all other considerations and influences, as the destroyer of character and individuality everywhere, it is the wickedest of all the forces that attack the defenceless child. The tenements are increasing in number, and so is “the element that becomes criminal because of lack of individuality and the self-respect that comes with it.”17

I am always made to think in connection with this subject of a story told me by a bright little woman of her friend’s kittens. There was a litter of them in the house and a jealous terrier dog to boot, whose one aim in life was to get rid of its mewing rivals. Out in the garden where the children played there was a sand-heap and the terrier’s trick was to bury alive in the sand any kitten it caught unawares. The children were constantly rushing to the rescue and unearthing their pets; on the day when my friend was there on a visit they were too late. The first warning of the tragedy in the garden came to the ladies when one of the children rushed in, all red and excited, with bulging eyes. “There,” she said, dropping the dead kitten out of her apron before them, “a perfectly good cat spoiled!”

Perfectly good children, as good as any on the Avenue, are spoiled every day by the tenement; only we have not done with them then, as the terrier had with the kitten. There is still posterity to reckon with.

What this question of heredity amounts to, whether in the past or in the future, I do not know. I have not had opportunity enough of observing. No one has that I know of. Those who have had the most disagree in their conclusions, or have come to none. I have known numerous instances of criminality, running apparently in families for generations, but there was always the desperate environment as the unknown factor in the make-up. Whether that bore the greatest share of the blame, or whether the reformation of the criminal to be effective should have begun with his grandfather, I could not tell. Besides, there was always the chance that the great-grandfather, or some one still farther back, of whom all trace was lost, might have been a paragon of virtue, even if his descendant was a thief, and so there was no telling just where to begin. In general I am inclined to think with such practical philanthropists as Superintendent Barnard, of the Five Points House of Industry, the Manager of the Children’s Aid Society, Superintendent E. Fellows Jenkins, of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, and Mr. Israel C. Jones, who for more than thirty years was in charge of the House of Refuge, that the bugbear of heredity is not nearly as formidable as we have half taught ourselves to think. It is rather a question of getting hold of the child early enough before the evil influences surrounding him have got a firm grip on him. Among a mass of evidence quoted in support of this belief, perhaps this instance, related by Superintendent Jones in The Independent last March, is as convincing as any:

Thirty years ago there was a depraved family living adjacent to what is now a part of the city of New York. The mother was not only dishonest, but exceedingly intemperate, wholly neglectful of her duties as a mother, and frequently served terms in jail until she finally died. The father was also dissipated and neglectful. It was a miserable existence for the children.

Two of the little boys, in connection with two other boys in the neighborhood, were arrested, tried, and found guilty of entering a house in the daytime and stealing. In course of time both of these boys were indentured. One remained in his place and the other left for another part of the country, where he died. He was a reputable lad.

The first boy, in one way and another, got a few pennies together with which he purchased books. After a time he proposed to his master that he be allowed to present himself for examination as a teacher. The necessary consent was given, he presented himself, and was awarded a “grade A” certificate.

Two years from that time he came to the House of Refuge, as proud as a man could be, and exhibited to me his certificate. He then entered a law office, diligently pursued his studies, and was admitted to the bar. He was made a judge, and is now chief magistrate of the court in the city where he lives.

His sister, a little girl, used to come to the Refuge with her mother, wearing nothing but a thin cloak in very cold weather, almost perishing with the cold. As soon as this young man got on his feet he rescued the little girl. He placed her in a school; she finally graduated from the Normal School, and to-day holds an excellent position in the schools in the State where she lives.

The records of the three reformatory institutions before mentioned throw their own light upon the question of what makes criminals of the young. At the Elmira Reformatory, of more than five thousand prisoners only a little over one per cent. were shown to have kept good company prior to their coming there. One and a half per cent. are put down under this head as “doubtful,” while the character of association is recorded for 41.2 per cent. as “not good,” and for 55.9 per cent. as “positively bad.” Three-fourths possessed no culture or only the slightest. As to moral sense, 42.6 per cent. had absolutely none, 35 per cent. “possibly some.” Only 7.6 per cent. came from good homes. Of the rest 39.8 per cent. had homes that are recorded as “fair only,” and 52.6 per cent. downright bad homes; 4.8 per cent. had pauper, and 76.8 per cent. poor parents; 38.4 per cent. of the prisoners had drunken parents, and 13 per cent. parents of doubtful sobriety. Of more than twenty-two thousand inmates of the Juvenile Asylum in thirty-nine years one-fourth had either a drunken father or mother, or both. At the Protectory the percentage of drunkenness in parents was not quite one-fifth among over three thousand children cared for in the institution last year.

There is never any lack of trashy novels and cheap shows in New York, and the children who earn money selling newspapers or otherwise take to them as ducks do to water. They fall in well with the ways of the street that are showy always, however threadbare may be the cloth. As for that, it is simply the cheap side of our national extravagance.

The cigarette, if not a cause, is at least the mean accessory of half the mischief of the street. And I am not sure it is not a cause too. It is an inexorable creditor that has goaded many a boy to stealing; for cigarettes cost money, and they do not encourage industry. Of course there is a law against the cigarette, or rather against the boy smoking it who is not old enough to work—there is law in plenty, usually, if that would only make people good. It don’t in the matter of the cigarette. It helps make the boy bad by adding the relish of law-breaking to his enjoyment of the smoke. Nobody stops him.

The mania for gambling is all but universal. Every street child is a born gambler; he has nothing to lose and all to win. He begins by “shooting craps” in the street and ends by “chucking dice” in the saloon, two names for the same thing, sure to lead to the same goal. By the time he has acquired individual standing in the saloon, his long apprenticeship has left little or nothing for him to learn of the bad it has to teach. Never for his own sake is he turned away with the growler when he comes to have it filled; once in a while for the saloon-keeper’s, if that worthy suspects in him a decoy and a “job.” Just for the sake of the experiment, not because I expected it to develop anything new, I chose at random, while writing this chapter, a saloon in a tenement house district on the East Side and posted a man, whom I could trust implicitly, at the door with orders to count the children under age who went out and in with beer-jugs in open defiance of law. Neither he nor I had ever been in or even seen the saloon before. He reported as the result of three and a half hours’ watch at noon and in the evening a total of fourteen—ten boys and a girl under ten years of age, and three girls between ten and fourteen years, not counting a little boy who bought a bottle of ginger. It was a cool, damp day; not a thirsty day, or the number would probably have been twice as great. There was not the least concealment about the transaction in any of the fourteen cases. The children were evidently old customers.

The law that failed to save the boy while there was time yet to make a useful citizen of him provides the means of catching him when his training begins to bear fruit that threatens the public peace. Then it is with the same blundering disregard of common sense and common decency that marked his prosecution as a truant that the half grown lad is dragged into a police court and thrust into a prison-pen with hardened thieves and criminals to learn the lessons they have to teach him. The one thing New York needs most after a truant home is a special court for the trial of youthful offenders only. I am glad to say that this want seems at last in a way to be supplied. The last Legislature authorized the establishment of such a court, and it may be that even as these pages see the light this blot upon our city is about to be wiped out.

Lastly, but not least, the Church is to blame for deserting the poor in their need. It is an old story that the churches have moved uptown with the wealth and fashion, leaving the poor crowds to find their way to heaven as best they could, and that the crowds have paid them back in their own coin by denying that they, the churches, knew the way at all. The Church has something to answer for; but it is a healthy sign at least that it is accepting the responsibility and professing anxiety to meet it. In much of the best work done among the poor and for the poor it has lately taken the lead, and it is not likely that any more of the churches will desert the downtown field, with the approval of Christian men and women at least.

Little enough of the light I promised in the opening chapter has struggled through these pages so far. We have looked upon the dark side of the picture; but there is a brighter. If the battle with ignorance, with misery, and with vice has but just begun, if the army that confronts us is strong, too strong, in numbers still and in malice—the gauntlet has been thrown down, the war waged, and blows struck that tell. They augur victory, for we have cut off the enemy’s supplies and turned his flank. As I showed in the case of the immigrant Jews and the Italians, we have captured his recruits. With a firm grip on these, we may hope to win, for the rest of the problem ought to be and can be solved. With our own we should be able to settle, if there is any virtue in our school and our system of government. In this, as in all things, the public conscience must be stirred before the community’s machinery for securing justice can move. That it has been stirred, profoundly and to useful purpose, the multiplication in our day of charities for attaining the ends the law has failed to reach, gives evidence. Their number is so great that mention can be made here merely of a few of the most important and typical efforts along the line. A register of all those that deal with the children especially, as compiled by the Charity Organization Society, will be found in an appendix to this book. Before we proceed to look at the results achieved through endeavors to stop the waste down at the bottom by private reinforcement of the public school, we will glance briefly at two of the charities that have a plainer purpose—if I may so put it without disparagement to the rest—that look upon the child merely as a child worth saving for its own sake, because it is helpless and poor and wretched. Both of them represent distinct departures in charitable work. Both, to the everlasting credit of our city be it said, had their birth here, and in this generation, and from New York their blessings have been carried to the farthest lands. One is the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, known far and near now as the Children’s Society, whose strong and beneficent plan has been embodied in the structure of law of half the civilized nations of the world. The other, always spoken of as the “Fresh Air Fund,” never had law or structural organization of any kind, save the law of love, laid down on the Mount for all time; but the life of that divine command throbs in it and has touched the heart of mankind wherever its story has been told.

CHAPTER IX.

LITTLE MARY ELLEN’S LEGACY

ON a thriving farm up in Central New York a happy young wife goes singing about her household work to-day who once as a helpless, wretched waif in the great city through her very helplessness and misery stirred up a social revolution whose waves beat literally upon the farthest shores. The story of little Mary Ellen moved New York eighteen years ago as it had scarce ever been stirred by news of disaster or distress before. In the simple but eloquent language of the public record it is thus told: “In the summer of 1874 a poor woman lay dying in the last stages of consumption in a miserable little room on the top floor of a big tenement in this city. A Methodist missionary, visiting among the poor, found her there and asked what she could do to soothe her sufferings. ‘My time is short,’ said the sick woman, ‘but I cannot die in peace while the miserable little girl whom they call Mary Ellen is being beaten day and night by her step-mother next door to my room.’ She told how the screams of the child were heard at all hours. She was locked in the room, she understood. It had been so for months, while she had been lying ill there. Prompted by the natural instinct of humanity, the missionary sought the aid of the police, but she was told that it was necessary to furnish evidence before an arrest could be made. ‘Unless you can prove that an offence has been committed we cannot interfere, and all you know is hearsay.’ She next went to several benevolent societies in the city whose object it was to care for children, and asked their interference in behalf of the child. The reply was: ‘If the child is legally brought to us, and is a proper subject, we will take it; otherwise we cannot act in the matter.’ In turn then she consulted several excellent charitable citizens as to what she should do. They replied: ‘It is a dangerous thing to interfere between parent and child, and you might get yourself into trouble if you did so, as parents are proverbially the best guardians of their own children.’ Finally, in despair, with the piteous appeals of the dying woman ringing in her ears, she said: ‘I will make one more effort to save this child. There is one man in this city who has never turned a deaf ear to the cry of the helpless, and who has spent his life in just this work for the benefit of unoffending animals. I will go to Henry Bergh.’

“She went, and the great friend of the dumb brute found a way. ‘The child is an animal,’ he said, ‘if there is no justice for it as a human being, it shall at least have the rights of the stray cur in the street. It shall not be abused.’ And thus was written the first bill of rights for the friendless waif the world over. The appearance of the starved, half-naked, and bruised child when it was brought into court wrapped in a horse-blanket caused a sensation that stirred the public conscience to its very depths. Complaints poured in upon Mr. Bergh; so many cases of child-beating and fiendish cruelty came to light in a little while, so many little savages were hauled forth from their dens of misery, that the community stood aghast. A meeting of citizens was called and an association for the defence of outraged childhood was formed, out of which grew the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children that was formally incorporated in the following year. By that time Mary Ellen was safe in a good home. She never saw her tormentor again. The woman, whose name was Connolly, was not her mother. She steadily refused to tell where she got the child, and the mystery of its descent was never solved. The wretched woman was sent to the Island and forgotten.

John D. Wright, a venerable Quaker merchant, was chosen the first President of the Society. Upon the original call for the first meeting, preserved in the archives of the Society, may still be read a foot-note in his handwriting, quaintly amending the date to read, Quaker fashion, “12th mo. 15th 1874.” A year later, in his first review of the work that was before the young society, he wrote, “Ample laws have been passed by the Legislature of this State for the protection of and prevention of cruelty to little children. The trouble seems to be that it is nobody’s business to enforce them. Existing societies have as much, nay more to do than they can attend to in providing for those entrusted to their care. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children proposes to enforce by lawful means and with energy those laws, not vindictively, not to gain public applause, but to convince those who cruelly ill-treat and shamefully neglect little children that the time has passed when this can be done, in this State at least, with impunity.”

The promise has been faithfully kept. The old Quaker is dead, but his work goes on. The good that he did lives after him, and will live forever. The applause of the crowd his Society has not always won; but it has merited the confidence and approval of all right-thinking and right-feeling men. Its aggressive advocacy of defenceless childhood, always and everywhere, is to-day reflected from the statute-books of every State in the American Union, and well-nigh every civilized government abroad, in laws that sprang directly from its fearless crusade.

In theory it had always been the duty of the State to protect the child “in person, and property, and in its opportunity for life, liberty, and happiness,” even against a worthless parent; in practice it held to the convenient view that, after all, the parent had the first right to the child and knew what was best for it. The result in many cases was thus described in the tenth annual report of the Society by President Elbridge T. Gerry, who in 1879 had succeeded Mr. Wright and has ever since been so closely identified with its work that it is as often spoken of nowadays as Mr. Gerry’s Society as under its corporate name:

“Impecunious parents drove them from their miserable homes at all hours of the day and night to beg and steal. They were trained as acrobats at the risk of life and limb, and beaten cruelly if they failed. They were sent at night to procure liquor for parents too drunk to venture themselves into the streets. They were drilled in juvenile operas and song-and-dance variety business until their voices were cracked, their growth stunted, and their health permanently ruined by exposure and want of rest. Numbers of young Italians were imported by padroni under promises of a speedy return, and then sent out on the streets to play on musical instruments, to peddle flowers and small wares to the passers-by, and too often as a cover for immorality. Their surroundings were those of vice, profanity, and obscenity. Their only amusements were the dance-halls, the cheap theatres and museums, and the saloons. Their acquaintances were those hardened in sin, and both boys and girls soon became adepts in crime, and entered unhesitatingly on the downward path. Beaten and abused at home, treated worse than animals, no other result could be expected. In the prisons, to which sooner or later these unhappy children gravitated, there was no separation of them from hardened criminals. Their previous education in vice rendered them apt scholars in the school of crime, and they ripened into criminals as they advanced in years.”

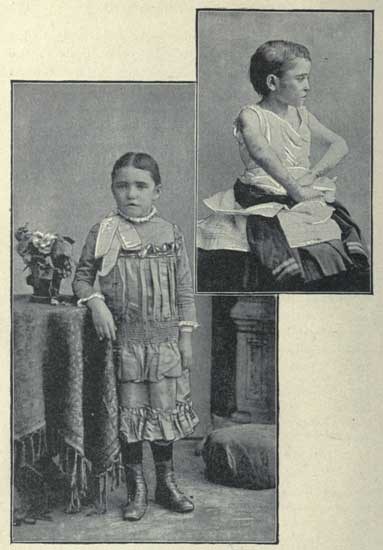

CASE NO. 25,745 ON THE SOCIETY BLOTTER: ANNIE WOLFF, AGED SEVEN YEARS, AS SHE WAS DRIVEN FORTH BY HER CRUEL STEP-MOTHER, BEATEN AND STARVED, WITH HER ARMS TIED UPON HER BACK; AND AS SHE APPEARED AFTER SIX MONTHS IN THE SOCIETY’S CARE.

All that has not been changed in the seventeen years that have passed; to remodel depraved human nature has been beyond the power of the Society; but step by step under its prompting the law has been changed and strengthened; step by step life has been breathed into its dead letter, until now it is as able and willing to protect the child against violence or absolute cruelty as the Society is to enforce its protection. There is work enough for it to do yet. I have outlined some in the preceding chapters. In the past year (1891) it investigated 7,695 complaints and rescued 3,683 children from pernicious surroundings, some of them from a worse fate than death. “But let it not be supposed from this,” writes the Superintendent, “that crimes of and against children are on the increase. As a matter of fact wrongs to children have been materially lessened in New York by the Society’s action and influence during the past seventeen years. Some have entirely disappeared, having been eradicated root and branch from New York life, and an influence for good has been felt by the children themselves, as shown by the great diminution in juvenile delinquency from 1875, when the Society was first organized, to 1891, the figures indicating a decrease of fully fifty per cent.”18

Other charitable efforts, working along the same line, contributed their share, perhaps the greater, to the latter result, but the Society’s influence upon the environment that shapes the childish mind and character, as well as upon the child itself, is undoubted. It is seen in the hot haste with which a general cleaning up and setting to rights is begun in a block of tenement barracks the moment the “cruelty man” heaves in sight; in the “holy horror” the child-beater has of him and his mission, and in the altered attitude of his victim, who not rarely nowadays confronts his tormentor with the threat, “if you do that I will go to the Children’s Society,” always effective except when drink blinds the wretch to consequences.

The Society had hardly been in existence four years when it came into collision with the padrone and his abominable system of child slavery. These traders in human misery, adventurers of the worst type, made a practice of hiring the children of the poorest peasants in the Neapolitan mountain districts, to serve them begging, singing, and playing in the streets of American cities. The contract was for a term of years at the end of which they were to return the child and pay a fixed sum, a miserable pittance, to the parents for its use, but, practically, the bargain amounted to a sale, except that the money was never paid. The children left their homes never to return. They were shipped from Naples to Marseilles, and made to walk all the way through France, singing, playing, and dancing in the towns and villages through which they passed, to a seaport where they embarked for America. Upon their arrival here they were brought to a rendezvous in some out-of-the-way slum and taken in hand by the padrone, the partner of the one who had hired them abroad. He sent them out to play in the streets by day, singing and dancing in tune to their alleged music, and by night made them perform in the lowest dens in the city. All the money they made the padrone took from them, beating and starving them if they did not bring home enough. None of it ever reached their parents. Under this treatment the boys grew up thieves—the girls worse. The life soon wore them out, and the Potter’s Field claimed them before their term of slavery was at an end, according to the contract. In far-off Italy the simple peasants waited anxiously for the return of little Tomaso or Antonia with the coveted American gold. No word ever came of them.

The vile traffic had been broken up in England only to be transferred to America. The Italian government had protested. Congress had passed an act making it a felony for anyone knowingly to bring into the United States any person inveigled or forcibly kidnapped in any other country, with the intent to hold him here in involuntary service. But these children were not only unable to either speak or understand English, they were compelled, under horrible threats, to tell anyone who asked that the padrone was their father, brother, or other near relative. To get the evidence upon which to proceed against the padrone was a task of exceeding difficulty, but it was finally accomplished by co-operation of the Italian government with the Society’s agents in the case of the padrone Ancarola, who, in November, 1879, brought over from Italy seven boy slaves, between nine and thirteen years old, with their outfit of harps and violins. They were seized, and the padrone, who escaped from the steamer, was arrested in a Crosby Street groggery five days later. Before a jury in the United States Court the whole vile scheme was laid bare. One of the boys testified that Ancarola had paid his mother 20 lire (about four dollars) and his uncle 60 lire. For this sum he was to serve the padrone four years. Ancarola was convicted and sent to the penitentiary. The children were returned to their homes.