полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

7. Appearance and mode of life.

In stature the Baigas are a little taller than most other tribes, and though they have a tendency to the flat nose of the Gonds, their foreheads and the general shape of their heads are of a better mould. Colonel Ward states that the members of the tribe inhabiting the Maikal range in Mandla are a much finer race than those living nearer the open country.94 Their figures are very nearly perfect, says Colonel Bloomfield,95 and their wiry limbs, unburdened by superfluous flesh, will carry them over very great distances and over places inaccessible to most human beings, while their compact bodies need no other nutriment than the scanty fare afforded by their native forests. They are born hunters, hardy and active in the chase, and exceedingly bold and courageous. In character they are naturally simple, honest and truthful, and when their fear of a stranger has been dissipated are most companionable folk. A small hut, 6 or 7 feet high at the ridge, made of split bamboos and mud, with a neat veranda in front thatched with leaves and grass, forms the Baiga’s residence, and if it is burnt down, or abandoned on a visitation of epidemic disease, he can build another in the space of a day. A rough earthen vessel to hold water, leaves for plates, gourds for drinking-vessels, a piece of matting to sleep on, and a small axe, a sickle and a spear, exhaust the inventory of the Baiga’s furniture, and the money value of the whole would not exceed a rupee.96 The Baigas never live in a village with other castes, but have their huts some distance away from the village in the jungle. Unlike the other tribes also, the Baiga prefers his house to stand alone and at some little distance from those of his fellow-tribesmen. While nominally belonging to the village near which they dwell, so separate and distinct are they from the rest of people that in the famine of 1897 cases were found of starving Baiga hamlets only a few hundred yards away from the village proper in which ample relief was being given. On being questioned as to why they had not caused the Baigas to be helped, the other villagers said, ‘We did not remember them’; and when the Baigas were asked why they did not apply for relief, they said, ‘We did not think it was meant for Baigas.’

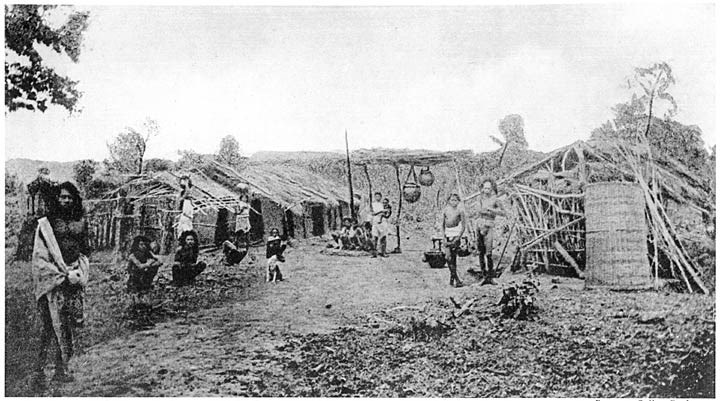

Baiga village, Bālāghāt District.

8. Dress and food.

Their dress is of the most simple description, a small strip of rag between the legs and another wisp for a head-covering sufficing for the men, though the women are decently covered from their shoulders to half-way between the thighs and knees. A Baiga may be known by his scanty clothing and tangled hair, and his wife by the way in which her single garment is arranged so as to provide a safe sitting-place in it for her child. Baiga women have been seen at work in the field transplanting rice with babies comfortably seated in their cloth, one sometimes supported on either hip with their arms and legs out, while the mother was stooping low, hour after hour, handling the rice plants. A girl is tattooed on the forehead at the age of five, and over her whole body before she is married, both for the sake of ornament and because the practice is considered beneficial to the health. The Baigas are usually without blankets or warm clothing, and in the cold season they sleep round a wood fire kept burning or smouldering all night, stray sparks from which may alight on their tough skins without being felt. Mr. Lampard relates that on one occasion a number of Baiga men were supplied by the Mission under his charge with large new cloths to cover their bodies with and make them presentable on appearance in church. On the second Sunday, however, they came with their cloths burnt full of small holes; and they explained that the damage had been done at night while they were sleeping round the fire.

A Baiga, Mr. Lampard continues, is speedily discerned in a forest village bazār, and is the most interesting object in it. His almost nude figure, wild, tangled hair innocent of such inventions as brush or comb, lithe wiry limbs and jungly and uncivilised appearance, mark him out at once. He generally brings a few mats or baskets which he has made, or fruits, roots, honey, horns of animals, or other jungle products which he has collected, for sale, and with the sum obtained (a few pice or annas at the most) he proceeds to make his weekly purchases, changing his pice into cowrie shells, of which he receives eighty for each one. He buys tobacco, salt, chillies and other sundries, besides as much of kodon, kutki, or perhaps rice, as he can afford, always leaving a trifle to be expended at the liquor shop before departing for home. The various purchases are tied up in the corners of the bit of rag twisted round his head. Unlike pieces of cloth known to civilisation, which usually have four corners, the Baiga’s headgear appears to be nothing but corners, and when the shopping is done the strip of rag may have a dozen minute bundles tied up in it.

In Baihar of Bālāghāt buying and selling are conducted on perhaps the most minute scale known, and if a Baiga has one or two pice97 to lay out he will spend no inconsiderable time over it. Grain is sold in small measures holding about four ounces called baraiyas, but each of these has a layer of mud at the bottom of varying degrees of thickness, so as to reduce its capacity. Before a purchase can be made it must be settled by whose baraiya the grain is to be measured, and the seller and purchaser each refuse the other’s as being unfair to himself, until at length after discussion some neutral person’s baraiya is selected as a compromise. Their food consists largely of forest fruits and roots with a scanty allowance of rice or the light millets, and they can go without nourishment for periods which appear extraordinary to civilised man. They eat the flesh of almost all animals, though the more civilised abjure beef and monkeys. They will take food from a Gond but not from a Brāhman. The Baiga dearly loves the common country liquor made from the mahua flower, and this is consumed as largely as funds will permit of at weddings, funerals and other social gatherings, and also if obtainable at other times. They have a tribal panchāyat or committee which imposes penalties for social offences, one punishment being the abstention from meat for a fixed period. A girl going wrong with a man of the caste is punished by a fine, but cases of unchastity among unmarried Baiga girls are rare. Among their pastimes dancing is one of the chief, and in their favourite dance, known as karma, the men and women form long lines opposite to each other with the musicians between them. One of the instruments, a drum called māndar, gives out a deep bass note which can be heard for miles. The two lines advance and retire, everybody singing at the same time, and when the dancers get fully into the time and swing, the pace increases, the drums beat furiously, the voices of the singers rise higher and higher, and by the light of the bonfires which are kept burning the whole scene is wild in the extreme.

9. Occupation.

The Baigas formerly practised only shifting cultivation, burning down patches of jungle and sowing seed on the ground fertilised by the ashes after the breaking of the rains. Now that this method has been prohibited in Government forest, attempts have been made to train them to regular cultivation, but with indifferent success in Bālāghāt. An idea of the difficulties to be encountered may be obtained from the fact that in some villages the Baiga cultivators, if left unwatched, would dig up the grain which they had themselves sown as seed in their fields and eat it; while the plough-cattle which were given to them invariably developed diseases in spite of all precautions, as a result of which they found their way sooner or later to the Baiga’s cooking-pot. But they are gradually adopting settled habits, and in Mandla, where a considerable block of forest was allotted to them in which they might continue their destructive practice of shifting sowings, it is reported that the majority have now become regular cultivators. One explanation of their refusal to till the ground is that they consider it a sin to lacerate the breast of their mother earth with a ploughshare. They also say that God made the jungle to produce everything necessary for the sustenance of men and made the Baigas kings of the forest, giving them wisdom to discover the things provided for them. To Gonds and others who had not this knowledge, the inferior occupation of tilling the land was left. The men never become farmservants, but during the cultivating season they work for hire at uprooting the rice seedlings for transplantation; they do no other agricultural labour for others. Women do the actual transplantation of rice and work as harvesters. The men make bamboo mats and baskets, which they sell in the village weekly markets. They also collect and sell honey and other forest products, and are most expert at all work that can be done with an axe, making excellent woodcutters. But they show no aptitude in acquiring the use of any other implement, and dislike steady continuous labour, preferring to do a few days’ work and then rest in their homes for a like period before beginning again. Their skill and dexterity in the use of the axe in hunting is extraordinary. Small deer, hares and peacocks are often knocked over by throwing it at them, and panthers and other large animals are occasionally killed with a single blow. If one of two Baigas is carried off by a tiger, the survivor will almost always make a determined and often successful attempt to rescue him with nothing more formidable than an axe or a stick. They are expert trackers, and are also clever at setting traps and snares, while, like Korkus, they catch fish by damming streams in the hot weather and throwing into the pool thus formed some leaf or root which stupefies them. Even in a famine year, Mr. Low says, a Baiga can collect a large basketful of roots in a single day; and if the bamboo seeds he is amply provided for. Nowadays Baiga cultivators may occasionally be met with who have taken to regular cultivation and become quite prosperous, owning a number of cattle.

10. Language.

As already stated, the Baigas have completely forgotten their own language, and in the Satpūra hills they speak a broken form of Hindi, though they have a certain number of words and expressions peculiar to the caste.

Bairāgi

1. Definition of name and statistics.

Bairāgi,98 Sādhu.—The general term for members of the Vishnuite religious orders, who formerly as a rule lived by mendicancy. The Bairāgis have now, however, become a caste. In 1911 they numbered 38,000 persons in the Provinces, being distributed over all Districts and States. The name Bairāgi is supposed to come from the Sanskrit Vairāgya and to signify one who is free from human passions. Bairāga is also the term for the crutched stick which such mendicants frequently carry about with them and lean upon, either sitting or standing, and which in case of need would serve them as a weapon. Platts considers99 that the name of the order comes from the Sanskrit abstract term, and the crutch therefore apparently obtained its name from being used by members of the order. Properly, a religious mendicant of any Vishnuite sect should be called a Bairāgi. But the term is not generally applied to the more distinctive sects as the Kabīrpanthi, Swāmi-Nārāyan, Satnāmi and others, some of which are almost separated from Hinduism, nor to the Sikh religious orders, nor the Chaitanya sect of Bengal. A proper Bairāgi is one whose principal deity is either Vishnu or either of his great incarnations, Rāma and Krishna.

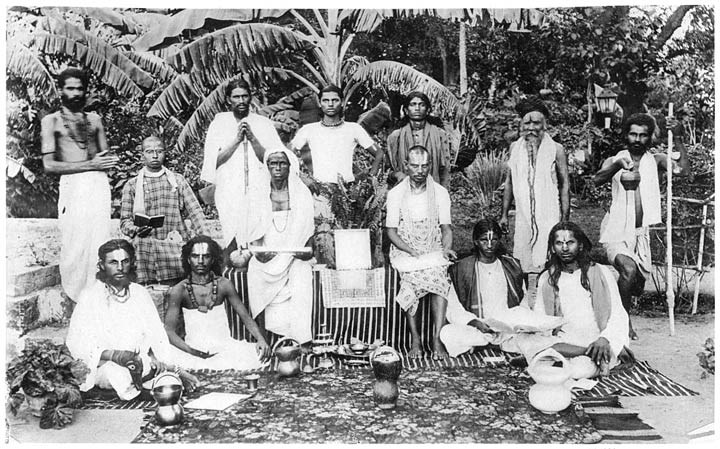

Hindu mendicants with sect-marks.

2. The four Sampradāyas or main orders.

It is generally held that there are four Sampradāyas or main sects of Bairāgis. These are—

(a) The Rāmānujis, the followers of the first prominent Vishnuite reformer Rāmānuj in southern India, with whom are classed the Rāmānandis or adherents of his great disciple Rāmānand in northern India. Both these are also called Sri Vaishnava, that is, the principal or original Vaishnava sect.

(b) The Nīmānandi, Nīmāt or Nīmbāditya sect, followers of a saint called Nīmānand.

(c) The Vishnu-Swāmi or Vallabhachārya sect, worshippers of Krishna and Rādha.

(d) The Mādhavachārya sect of southern India.

It will be desirable to give a few particulars of each of these, mainly taken from Wilson’s Hindu Sects and Dr. Bhattachārya’s Hindu Castes and Sects.

3. The Rāmānujis.

Rāmānuj was the first great Vishnuite prophet, and lived in southern India in the eleventh or twelfth century on an island in the Kāveri river near Trichinopoly. He preached the worship of a supreme spirit, Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, and taught that men also had souls or spirits, and that matter was lifeless. He was a strong opponent of the cult of Siva, then predominant in southern India, and of phallic worship. He, however, admitted only the higher castes into his order, and cannot therefore be considered as the founder of the liberalising principle of Vishnuism. The superiors of the Rāmānuja sect are called Achārya, and rank highest among the priests of the Vishnuite orders. The most striking feature in the practice of the Rāmānujis is the separate preparation and scrupulous privacy of their meals. They must not eat in cotton garments, but must bathe, and then put on wool or silk. The teachers allow their select pupils to assist them, but in general all the Rāmānujis cook for themselves, and should the meal during this process, or while they are eating, attract even the look of a stranger, the operation is instantly stopped and the viands buried in the ground. The Rāmānujis address each other with the salutation Dasoham, or ‘I am your slave,’ accompanied with the Pranām or slight inclination of the head and the application of joined hands to the forehead. To the Achāryas or superiors the other members of the sect perform the Ashtanga or prostration of the body with eight parts touching the ground. The tilak or sect-mark of the Rāmānujis consists of two perpendicular white lines from the roots of the hair to the top of the eyebrows, with a connecting white line at the base, and a third central line either of red or yellow. The Rāmānujis do not recognise the worship of Rādha, the consort of Krishna. The mendicant orders of the Sātanis and Dasaris of southern India are branches of this sect.

4. The Rāmānandis

Rāmānand, the great prophet of Vishnuism in northern India, and the real founder of the liberal doctrines of the cult, lived at Benāres at the end of the fourteenth century, and is supposed to have been a follower of Rāmānuj. He introduced, however, a great extension of his predecessor’s gospel in making his sect, nominally at least, open to all castes. He thus initiated the struggle against the social tyranny and exclusiveness of the caste system, which was carried to greater lengths by his disciples and successors, Kabīr, Nānak, Dādu, Rai Dās and others. These afterwards proclaimed the worship of one unseen god who could not be represented by idols, and the religious equality of all men, their tenets no doubt being considerably influenced by their observance of Islām, which had now become a principal religion of India. Rāmānand himself did not go so far, and remained a good Hindu, inculcating the special worship of Rāma and his consort Sīta. The Rāmaāandis consider the Rāmāyana as their most sacred book, and make pilgrimages to Ajodhia and Rāmnath.100 Their sect-mark consists of two white lines down the forehead with a red one between, but they are continued on to the nose, ending in a loop, instead of terminating at the line of the eyebrows, like that of the Rāmānujis. The Rāmānandis say that the mark on the nose represents the Singāsun or lion’s throne, while the two white lines up the forehead are Rāma and Lakhshman, and the centre red one is Sīta. Some of their devotees wear ochre-coloured clothes like the Sivite mendicants.

5. The Nīmānandis.

The second of the four orders is that of the Nīmānandis, called after a saint Nīmānand. He lived near Mathura Brindāban, and on one occasion was engaged in religious controversy with a Jain ascetic till sunset. He then offered his visitor some refreshment, but the Jain could not eat anything after sunset, so Nīmānand stopped the sun from setting, and ordered him to wait above a nīm tree till the meal was cooked and eaten under the tree, and this direction the sun duly obeyed. Hence Nīmānand, whose original name was Bhāskarachārya, was called by his new name after the tree, and was afterwards held to have been an incarnation of Vishnu or the Sun.

The doctrines of the sect, Mr. Growse states,101 are of a very enlightened character. Thus their tenet of salvation by faith is thought by many scholars to have been directly derived from the Gospels; while another article in their creed is the continuance of conscious individual existence in a future world, when the highest reward of the good will not be extinction, but the enjoyment of the visible presence of the divinity whom they have served while on earth. The Nīmānandis worship Krishna, and were the first sect, Dr. Bhattachārya states,102 to associate with him as a divine consort Rādha, the chief partner of his illicit loves.

Their headquarters are at Muttra, and their chief festival is the Janam-Ashtami103 or Krishna’s birthday. Their sect-mark consists of two white lines down the forehead with a black patch in the centre, which is called Shiāmbindini. Shiām means black, and is a name of Krishna. They also sometimes have a circular line across the nose, which represents the moon.

6. The Mādhavachāryas.

The third great order is that of the Mādhavas, named after a saint called Mādhavachārya in southern India. He attempted to reconcile the warring Sivites and Vishnuites by combining the worship of Krishna with that of Siva and Pārvati. The doctrine of the sect is that the human soul is different from the divine soul, and its members are therefore called dualists. They admit a distinction between the divine soul and the universe, and between the human soul and the material world. They deny also the possibility of Nirvāna or the absorption and extinction of the human soul in the divine essence. They destroy their thread at initiation, and also wear red clothes like the Sivite devotees, and like them also they carry a staff and water-pot. The tilak of the Mādhavachāryas is said to consist of two white lines down the forehead and continued on to the nose where they meet, with a black vertical line between them.

7. The Vallabhachāryas.

The fourth main order is the Vishnu-Swāmi, which is much better known as the Vallabhachārya sect, called after its founder Vallabha, who was born in A.D. 1479. The god Krishna appeared to him and ordered him to marry and set up a shrine to the god at Gokul near Mathura (Muttra). The sect worship Krishna in his character of Bāla Gopāla or the cowherd boy. Their temples are numerous all over India, and especially at Mathura and Brindāban, where Krishna was brought up as a cowherd. The temples at Benāres, Jagannāth and Dwārka are rich and important, but the most celebrated shrine is at Sri Nāthadwāra in Mewār. The image is said to have transported itself thither from Mathura, when Aurāngzeb ordered its temple at Mathura to be destroyed. Krishna is here represented as a little boy in the act of supporting the mountain Govardhan on his finger to shelter the people from the storms of rain sent by Indra. The image is splendidly dressed and richly decorated with ornaments to the value of several thousand pounds. The images of Krishna in the temples are commonly known as Thākurji, and are either of stone or brass. At all Vallabhachārya temples there are eight daily services: the Mangala or morning levée, a little after sunrise, when the god is taken from his couch and bathed; the Sringāra, when he is attired in his jewels and seated on his throne; the Gwāla, when he is supposed to be starting to graze his cattle in the woods of Braj; the Rāj Bhog or midday meal, which, after presentation, is consumed by the priests and votaries who have assisted at the ceremonies; the Uttāpan, about three o’clock, when the god awakes from his siesta; the Bhog or evening collation; the Sandhiya or disrobing at sunset; and the Sayan or retiring to rest. The ritual is performed by the priests and the lay worshipper is only a spectator, who shows his reverence by the same forms as he would to a human superior.104

Anchorite sitting on iron nails.

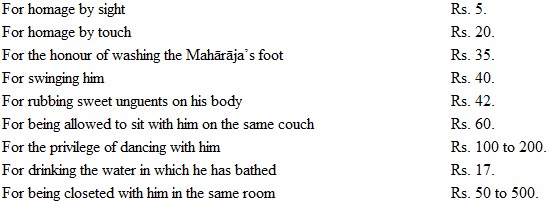

The priests of the sect are called Gokalastha Gosain or Mahārāja. They are considered to be incarnations of the god, and divine honours are paid to them. They always marry, and avow that union with the god is best obtained by indulgence in all bodily enjoyments. This doctrine has led to great licentiousness in some groups of the sect, especially on the part of the priests or Mahārājas. Women were taught to believe that the service of and contact with the priest were the most real form of worshipping the god, and that intercourse with him was equivalent to being united with the god. Dr. Bhattachārya quotes105 the following tariff for the privilege of obtaining different degrees of contact with the body of the Mahārāja or priest:

The public disapprobation caused by these practices and their bad effect on the morality of women culminated in the great Mahārāj libel suit in the Bombay High Court in 1862. Since then the objectionable features of the cult have to a large extent disappeared, while it has produced some priests of exceptional liberality and enlightenment. The tilak of the Vallabhachāryas is said to consist of two white lines down the forehead, forming a half-circle at its base and a white dot between them. They will not admit the lower castes into the order, but only those from whom a Brāhman can take water.

8. Minor sects.

Besides the main sects as described above, Vaishnavism has produced many minor sects, consisting of the followers of some saint of special fame, and mendicants belonging to these are included in the body of Bairāgis. One or two legends concerning such saints may be given. A common order is that of the Bendiwāle, or those who wear a dot. Their founder began putting a red dot on his forehead between the two white lines in place of the long red line of the Rāmānandis. His associates asked him why he had dared to alter his tilak or sect-mark. He said that the goddess Jānki had given him the dot, and as a test he went and bathed in the Sarju river, and rubbed his forehead with water, and all the sect-mark was rubbed out except the dot. So the others recognised the special intervention of the goddess, and he founded a sect. Another sect is called the Chaturbhuji or four-armed, Chaturbhuj being an epithet of Vishnu. He was taking part in a feast when his loin-cloth came undone behind, and the others said to him that as this had happened, he had become impure at the feast. He replied, ‘Let him to whom the dhoti belongs tie it up,’ and immediately four arms sprang from his body, and while two continued to take food, the other two tied up his loin-cloth behind. Thus it was recognised that the Chaturbhuji Vishnu had appeared in him, and he was venerated.

9. The seven Akhāras.

Among the Bairāgis, besides the four Sampradāyas or main orders, there are seven Akhāras. These are military divisions or schools for training, and were instituted when the Bairāgis had to fight with the Gosains. Any member of one of the four Sampradāyas can belong to any one of the seven Akhāras, and a man can change his Akhāra as often as he likes, but not his Sampradāya. The Akhāras, with the exception of the Lasgaris, who change the red centre line of the Rāmanāndis into a white line, have no special sect-marks. They are distinguished by their flags or standards, which are elaborately decorated with gold thread embroidered on silk or sometimes with jewels, and cost two or three hundred rupees to prepare. These standards were carried by the Nāga or naked members of the Akhāra, who went in front and fought. Once in twelve years a great meeting of all the seven Akhāras is held at Allahābād, Nāsik, Ujjain or Hardwār, where they bathe and wash the image of the god in the water of the holy rivers. The quarrels between the Bairāgis and Gosains usually occurred at the sacred rivers, and the point of contention was which sect should bathe first. The following is a list of the seven Akhāras: Digambari, Khāki, Munjia, Kathia, Nirmohi, Nirbāni or Niranjani and Lasgari.