полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

11. Pious funeral observances.

Like pious Hindus as they were, the Badhaks were accustomed, whenever it was possible, to preserve the bones of their dead after the body had been burnt and carry them to the Ganges. If this was not possible, however, and the exigencies of their profession obliged them to make away with the body without the performance of due funeral rites, they cut off two or three fingers and sent these to the Ganges to be deposited instead of the whole body.63 In one case a dacoit, Kundana, was killed in an affray, and the others carried off his body and thrust it into a porcupine’s hole after cutting off three of the fingers. “We gave Kundana’s fingers to his mother,” Ajīt Singh stated, “and she sent them with due offerings and ceremonies to the Ganges by the hands of the family priest. She gave this priest money to purchase a cow, to be presented to the priests in the name of her deceased son, and to distribute in charity to the poor and to holy men. She got from us for these purposes eighty rupees over and above her son’s share of the booty, while his widow and children continued to receive their usual share of the takings of the gang so long as they remained with us.”

12. Taking the omens.

Before setting out on an expedition it was their regular custom to take the omens, and the following account may be quoted of the preliminaries to an expedition of the great leader, Meherbān Singh, who has already been mentioned: “In the latter end of that year, Meherbān and his brother set out and assembled their friends on the bank of the Bisori river, where the rate at which each member of the party should share in the spoil was determined in order to secure to the dependants of any one who should fall in the enterprise their due share, as well as to prevent inconvenient disputes during and after the expedition. The party assembled on this occasion, including women and children, amounted to two hundred, and when the shares had been determined the goats were sacrificed for the feast. Each leader and member of the gang dipped his finger in the blood and swore fidelity to his engagements and his associates under all circumstances. The whole feasted together and drank freely till the next evening, when Meherbān advanced with about twenty of the principal persons to a spot chosen a little way from the camp on the road they proposed to take in the expedition, and lifting up his hands in supplication said aloud, ‘If it be thy will, O God, and thine, Kāli, to prosper our undertaking for the sake of the blind and the lame, the widow and the orphan, who depend upon our exertions for subsistence, vouchsafe, we pray thee, the call of the female jackal.’ All his followers held up their hands in the same manner and repeated these words after him. All then sat down and waited in silence for the reply or spoke only in whispers. At last the cry of the female jackal was heard three times on the left, and believing her to have been inspired by the deity for their guidance they were all much rejoiced.” The following was another more elaborate method of taking omens described by Ajīt Singh: “When we speak of seeking omens from our gods or Devi Deota, we mean the spirits of those of our ancestors who performed great exploits in dacoity in their day, gained a great name and established lasting reputations. For instance, Mahājīt, my grandfather, and Sāhiba, his father, are called gods and admitted to be so by us all. We have all of us some such gods to be proud of among our ancestors; we propitiate them and ask for favourable omens from them before we enter upon any enterprise. We sometimes propitiate the Sūraj Deota (sun god) and seek good omens from him. We get two or three goats or rams, and sometimes even ten or eleven, at the place where we determine to take the auspices, and having assembled the principal men of the gang we put water into the mouth of one of them and pray to the sun and to our ancestors thus: ‘O thou Sun God! And O all ye other Gods! If we are to succeed in the enterprise we are about to undertake we pray you to cause these goats to shake their bodies.’ If they do not shake them after the gods have been thus duly invoked, the enterprise must not be entered upon and the goats are not sacrificed. We then try the auspices with wheat. We burn frankincense and scented wood and blow a shell; and taking out a pinch of wheat grains, put them on the cloth and count them. If they come up odd the omen is favourable, and if even it is bad. After this, which we call the auspices of the Akūt, we take that of the Siārni or female jackal. If it calls on the left it is good, but if on the right bad. If the omens turn out favourable in all three trials then we have no fear whatever, but if they are favourable in only one trial out of the three the enterprise must be given up.”

13. Suppression of dacoity.

Between 1837 and 1849 the suppression of the regular practice of armed dacoity was practically achieved by Colonel Sleeman. A number of officers were placed under his orders, and with small bodies of military and police were set to hunt down different bands of dacoits, following them all over India when necessary. And special Acts were passed to enable the offence of dacoity, wherever committed, to be tried by a competent magistrate in any part of India as had been done in the case of the Thugs. Many of the Badhaks received conditional pardons, and were drafted into the police in different stations, and an agricultural labour colony was also formed, but does not seem to have been altogether successful. During these twelve years more than 1200 dacoits in all were brought to trial, while some were killed during the operations, and no doubt many others escaped and took to other avocations, or became ordinary criminals when their armed gangs were broken up. In 1825 it had been estimated that the Oudh forests alone contained from 4000 to 6000 dacoits, while the property stolen in 1811 from known dacoities was valued at ten lakhs of rupees.

14. The Badhaks or Baoris at the present time.

The Badhaks still exist, and are well known as one of the worst classes of criminals, practising ordinary house-breaking and theft. The name Badhak is now less commonly used than those of Bāgri and Baori or Bāwaria, both of which were borne by the original Badhaks. The word Bāgri is derived from a tract of country in Mālwa which is known as the Bāgar or ‘hedge of thorns,’ because it is surrounded on all sides by wooded hills.64 There are Bāgri Jāts and Bāgri Rājpūts, many of whom are now highly respectable landholders. Bāwaria or Baori is derived from bānwar, a creeper, or the tendril of a vine, and hence a noose made originally from some fibrous plant and used for trapping animals, this being one of the primary occupations of the tribe.65 The term Badhak signifies a hunter or fowler, hence a robber or murderer (Platts). The Bāgris and Bāwarias are sometimes considered to be separate communities, but it is doubtful whether there is any real distinction between them. In Bombay the Bāgris are known as Vāghris by the common change of b into v. A good description of them is contained in Appendix C to Mr. Bhimbhai Kirpārām’s volume Hindus of Gujarat in the Bombay Gazetteer. He divides them into the Chunaria or lime-burners, the Dātonia or sellers of twig tooth-brushes, and two other groups, and states that, “They also keep fowls and sell eggs, catch birds and go as shikāris or hunters. They traffic in green parrots, which they buy from Bhīls and sell for a profit.”

15. Lizard-hunting.

Their strength and powers of endurance are great, the same writer states, and they consider that these qualities are obtained by the eating of the goh and sāndha or iguana lizards, which a Vāghri prizes very highly. This is also the case with the Bāwarias of the Punjab, who go out hunting lizards in the rains and may be seen returning with baskets full of live lizards, which exist for days without food and are killed and eaten fresh by degrees. Their method of hunting the lizard is described by Mr. Wilson as follows:66 “The lizard lives on grass, cannot bite severely, and is sluggish in his movements, so that he is easily caught. He digs a hole for himself of no great depth, and the easiest way to take him is to look out for the scarcely perceptible airhole and dig him out; but there are various ways of saving oneself this trouble. One, which I have seen, takes advantage of a habit the lizard has in cold weather (when he never comes out of his hole) of coming to the mouth for air and warmth. The Chūhra or other sportsman puts off his shoes and steals along the prairie till he sees signs of a lizard’s hole. This he approaches on tiptoe, raising over his head with both hands a mallet with a round sharp point, and fixing his eyes intently upon the hole. When close enough he brings down his mallet with all his might on the ground just behind the mouth of the hole, and is often successful in breaking the lizard’s back before he awakes to a sense of his danger. Another plan, which I have not seen, is to tie a wisp of grass to a long stick and move it over the hole so as to make a rustling noise. The lizard within thinks, ‘Oh here’s a snake! I may as well give in,’ and comes to the mouth of the hole, putting out his tail first so that he may not see his executioner. The sportsman seizes his tail and snatches him out before he has time to learn his mistake.” This common fondness for lizards is a point in favour of a connection between the Gujarāt Vāghris and the Punjab Bāwarias.

16. Social observances.

In Sirsa the great mass of the Bāwarias are not given to crime, and in Gujarāt also they do not appear to have special criminal tendencies. It is a curious point, however, that Mr. Bhimbhai Kirpārām emphasises the chastity of the women of the Gujarāt Vāghris.67 “When a family returns home after a money-making tour to Bombay or some other city, the women are taken before Vihāt (Devi), and with the women is brought a buffalo or a sheep that is tethered in front of Vihāt’s shrine. They must confess all, even their slightest shortcomings, such as the following: ‘Two weeks ago, when begging in Pārsi Bazār-street, a drunken sailor caught me by the hand. Another day a Mīyan or Musalmān ogled me, and forgive me, Devi, my looks encouraged him.’ If Devi is satisfied the sheep or buffalo shivers, and is then sacrificed and provides a feast for the caste.”68 On the other hand, Mr. Crooke states69 that in northern India, “The standard of morality is very low because in Muzaffarnagar it is extremely rare for a Bāwaria woman to live with her husband. Almost invariably she lives with another man: but the official husband is responsible for the children.” The great difference in the standard of morality is certainly surprising.

In Gujarāt70 the Vāghris have gurus or religious preceptors of their own. These men take an eight-anna silver piece and whisper in the ear of their disciples “Be immortal.”… “The Bhuvas or priest-mediums play an important part in many Vāghri ceremonies. A Bhuva is a male child born after the mother has made a vow to the goddess Vihāt or Devi that if a son be granted to her she will devote him to the service of the goddess. No Bhuva may cut or shave his hair on pain of a fine of ten rupees, and no Bhuva may eat carrion or food cooked by a Muhammadan.”

17. Criminal practices.

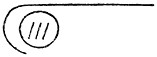

The criminal Bāgris still usually travel about in the disguise of Gosains and Bairāgis, and are very difficult of detection except to real religious mendicants. Their housebreaking implement or jemmy is known as Gyān, but in speaking of it they always add Dās, so that it sounds like the name of a Bairāgi.71 They are usually very much afraid of the gyān being discovered on their persons, and are careful to bury it in the ground at each halting-place, while on the march it may be concealed in a pack-saddle. The means of identifying them, Mr. Kennedy remarks,72 is by their family deo or god, which they carry about when wandering with their families. It consists of a brass or copper box containing grains of wheat and the seeds of a creeper, both soaked in ghī (melted butter). The box with a peacock’s feather and a bell is wrapped in two white and then in two red cloths, one of the white cloths having the print of a man’s hand dipped in goat’s blood upon it. The grains of wheat are used for taking the omens, a few being thrown up at sun-down and counted afterwards to see whether they are odd or even. When even, two grains are placed on the right hand of the omen-taker, and if this occurs three times running the auspices are considered to be favourable.73 Mr. Gayer74 notes that the Badhaks have usually from one to three brands from a hot iron on the inside of their left wrist. Those of them who are hunters brand the muscles of the left wrist in order to steady the hand when firing their matchlocks. The customs of wearing a peculiar necklace of small wooden beads and a kind of gold pin fixed to the front teeth, which Mr. Crooke75 records as having been prevalent some years ago, have apparently been since abandoned, as they are not mentioned in more recent accounts. The Dehliwāl and Mālpura Baorias have, Mr. Kennedy states,76 an interesting system of signs, which they mark on the walls of buildings at important corners, bridges and cross-roads and on the ground by the roadside with a stick, if no building is handy. The commonest is a loop, the straight line indicating the direction a gang or individual has taken:

The addition of a number of vertical strokes inside the loop signifies the number of males in a gang. If these strokes are enclosed by a circle it means that the gang is encamped in the vicinity; while a square inside a circle and line as below means that property has been secured by friends who have left in the direction pointed by the line. It is said that Baorias will follow one another up for fifty or even a hundred miles by means of these hieroglyphics. The signs are bold marks, sometimes even a foot or more in length, and are made where they will at once catch the eye. When the Mārwāri Baorias desire to indicate to others of their caste, who may follow in their footsteps, the route taken, a member of the gang, usually a woman, trails a stick in the dust as she walks along, leaving a spiral track on the ground. Another method of indicating the route taken is to place leaves under stones at intervals along the road.77 The form of crime most in favour among the ordinary Baoris is housebreaking by night. Their common practice is to make a hole in the wall beside the door through which the hand passes to raise the latch; and only occasionally they dig a hole in the base of the wall to admit of the passage of a man, while another favoured alternative is to break in through a barred window, the bars being quickly and forcibly bent and drawn out.78 One class of Mārwāri Bāgris are also expert coiners.

Bahna

1. Nomenclature and internal structure.

Bahna, Pinjāra, Dhunia. 79—The occupational caste of cotton-cleaners. The Bahnas numbered 48,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār in 1911. The large increase in the number of ginning-factories has ruined the Bahna’s trade of cleaning hand-ginned cotton, and as no distinction attaches to the name of Bahna it is possible that members of the caste who have taken to other occupations may have abandoned it and returned themselves simply as Muhammadans. The three names Bahna, Pinjāra, Dhunia appear to be used indifferently for the caste in this Province, though in other parts of India they are distinguished. Pinjāra is derived from the word pinjan used for a cotton-bow, and Dhunia is from dhunna, to card cotton. The caste is also known as Dhunak Pathāni. Though professing the Muhammadan religion, they still have many Hindu customs and ceremonies, and in the matter of inheritance our courts have held that they are subject to Hindu and not Muhammadan law.80 In Raipur a girl receives half the share of a boy in the division of inherited property. The caste appears to be a mixed occupational group, and is split into many territorial subcastes named after the different parts of the country from which its members have come, as Badharia from Badhas in Mīrzāpur, Sarsūtia from the Sāraswati river, Berāri of Berār, Dakhni from the Deccan, Telangi from Madras, Pardeshi from northern India, and so on. Two groups are occupational, the Newāris of Saugor, who make the thick newār tape used for the webbing of beds, and the Kanderas, who make fireworks and generally constitute a separate caste. There is considerable ground for supposing that the Bahnas are mainly derived from the caste of Telis or oil-pressers. In the Punjab Sir D. Ibbetson says81 that the Penja or cotton-scutcher is an occupational name applied to Telis who follow this profession; and that the Penja, Kasai and Teli are all of the same caste. Similarly in Nāsik the Telis and Pinjāras are said to form one community, under the government of a single panchāyat. In cases of dispute or misconduct the usual penalty is temporary excommunication, which is known as the stopping of food and water.82 The Telis are an enterprising community of very low status, and would therefore be naturally inclined to take to other occupations; many of them are shopkeepers, cultivators and landholders, and it is quite probable that in past times they took up the Bahna’s profession and changed their religion with the hope of improving their social status. The Telis are generally considered to be quarrelsome and talkative, and the Bahnas or Dhunias have the same characteristics. If one man abusing another lapses into Billingsgate, the other will say to him, ‘Hamko Julāha Dhunia neh jāno,’ or ‘Don’t talk to me as if I was a Julāha or a Dhunia.’

2. Marriage.

Some Bahnas have exogamous sections with Hindu names, while others are without these, and simply regulate their marriages by rules of relationship. They have the primitive Hindu custom of allowing a sister’s son to marry a brother’s daughter, but not vice versa. A man cannot marry his wife’s younger sister during her lifetime, nor her elder sister at any time. Children of the same foster-mother are also not allowed to marry. Their marriages are performed by a Kāzi with an imitation of the Nikāh rite. The bridegroom’s party sit under the marriage-shed, and the bride with the women of her party inside the house. The Kāzi selects two men, one from the bride’s party, who is known as the Nikāhi Bāp or ‘Marriage Father,’ and the other from the bridegroom’s, who is called the Gowāh or ‘Witness.’ These two men go to the bride and ask her whether she accepts the bridegroom, whose name is stated, for her husband. She answers in the affirmative, and mentions the amount of the dowry which she is to receive. The bridegroom, who has hitherto had a veil (mukhna) over his face, now takes it off, and the men go to him and ask him whether he accepts the bride. He replies that he does, and agrees to pay the dowry demanded by her. The Kāzi reads some texts and the guests are given a meal of rice and sugar. Many of the preliminaries to a Hindu marriage are performed by the more backward members of the caste, and until recently they erected a sacred post in the marriage-shed, but now they merely hang the green branch of a mango tree to the roof. The minimum amount of the mehar or dowry is said to be Rs. 125, but it is paid to the girl’s parents as a bride-price and not to herself, as among the Muhammadans. A widow is expected, but not obliged, to marry her deceased husband’s younger brother. Divorce is permitted by means of a written deed known as ‘Fārkhati.’

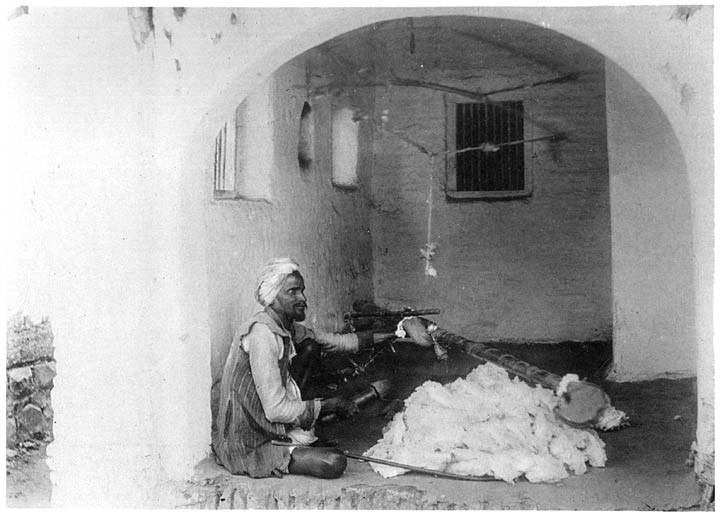

Pinjāra cleaning cotton.

3. Religious and other customs.

The Bahnas venerate Muhammad, and also worship the tombs of Muhammadan saints or Pīrs. A green sheet or cloth is spread over the tomb and a lamp is kept burning by it, while offerings of incense and flowers are made. When the new cotton crop has been gathered they lay some new cotton by their bow and mallet and make an offering of malīda or cakes of flour and sugar to it. They believe that two angels, one good and one bad, are perched continually on the shoulders of every man to record his good and evil deeds. And when an eclipse occurs they say that the sun and moon have gone behind a pinnacle or tower of the heavens. For exorcising evil spirits they write texts of the Korān on paper and burn them before the sufferer. The caste bury the dead with the feet pointing to the south. On the way to the grave each one of the mourners places his shoulder under the bier for a time, partaking of the impurity communicated by it. Incense is burnt daily in the name of a deceased person for forty days after his death, with the object probably of preventing his ghost from returning to haunt the house. Muhammadan beggars are fed on the tenth day. Similarly, after the birth of a child a woman is unclean for forty days, and cannot cook for her husband during that period. A child’s hair is cut for the first time on the tenth or twelfth day after birth, this being known as Jhālar. Some parents leave a lock of hair to grow on the head in the name of the famous saint Sheikh Farīd, thinking that they will thus ensure a long life for the child. It is probably in reality a way of preserving the Hindu choti or scalp-lock.

4. Occupation.

The hereditary calling83 of the Bahna is the cleaning or scutching of cotton, which is done by subjecting it to the vibration of a bow-string. The seed has been previously separated by a hand-gin, but the ginned cotton still contains much dirt, leaf-fibre and other rubbish, and to remove this is the Bahna’s task. The bow is somewhat in the shape of a harp, the wide end consisting of a broad piece of wood over which the string passes, being secured to a straight wooden bar at the back. At the narrow end the bar and string are fixed to an iron ring. The string is made of the sinew of some animal, and this renders the implement objectionable to Hindus, and may account for the Bahnas being Muhammadans. The club or mallet is a wooden implement shaped like a dumb-bell. The bow is suspended from the roof so as to hang just over the pile of loose cotton; and the worker twangs the string with the mallet and then draws the mallet across the string, each three or four times. The string strikes a small portion of the cotton, the fibre of which is scattered by the impact and thrown off in a uniform condition of soft fluff, all dirt being at the same time removed. This is the operation technically known as teasing. Buchanan remarked that women frequently did the work themselves at home, using a smaller kind of bow called dhunkara. The clean cotton is made up into balls, some of which are passed on to the spinner, while others are used for the filling of quilts and the padded coats worn in the cold weather. The ingenious though rather clumsy method of the Bahna has been superseded by the ginning-factory, and little or no cotton destined for the spindle is now cleaned by him. The caste have been forced to take to cultivation or field labour, while many have become cartmen and others are brokers, peons or constables. Nearly every house still has its pinjan or bow, but only a desultory use is made of this during the winter months. As it is principally used by a Muhammadan caste it seems a possible hypothesis that the cotton-bow was introduced into India by invaders of that religion. The name of the bow, pinjan, is, however, a Sanskrit derivative, and this is against the above theory. It has already been seen that the fact of animal sinew being used for the string would make it objectionable to Hindus. The Bahnas are subjected to considerable ridicule on account of their curious mixture of Hindu and Muhammadan ceremonies, amounting in some respects practically to a caricature of the rites of Islām; and further, they share with the weaver class the contempt shown to those who follow a calling considered more suitable for women than men. It is related that when the Mughal general Asaf Khān first made an expedition into the north of the Central Provinces he found the famous Gond-Rājpūt queen Durgāvati of the Garha-Mandla dynasty governing with success a large and prosperous state in this locality. He thought a country ruled by a woman should fall an easy prey to the Muhammadan arms, and to show his contempt for her power he sent her a golden spindle. The queen retorted by a present of a gold cotton-cleaner’s bow, and this so enraged the Mughal that he proceeded to attack the Gond kingdom. The story indicates that cotton-carding is considered a Muhammadan profession, and also that it is held in contempt.