полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

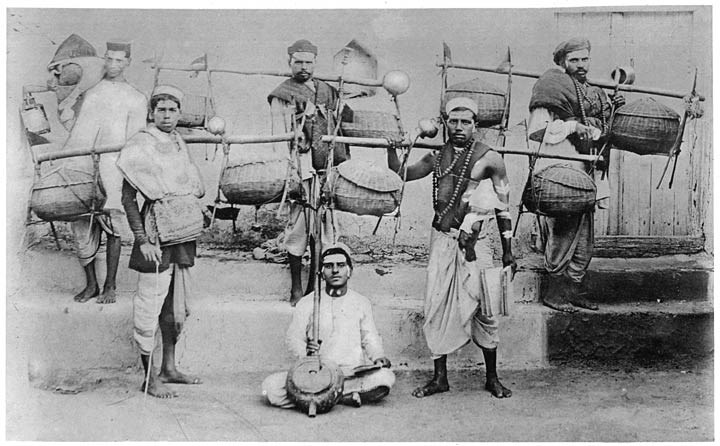

Pilgrims carrying water of the river Nerbudda.

The name of the Digamber or Meghdamber signifies sky-clad or cloud-clad, that is naked. They do penance in the rainy season by sitting naked in the rain for two or three hours a day with an earthen pot on the head and the hands inserted in two others so that they cannot rub the skin. In the dry season they wear only a little cloth round the waist and ashes over the rest of the body. The ashes are produced from burnt cowdung picked up off the ground, and not mixed with straw like that which is prepared for fuel.

The Khāki Bairāgis also rub ashes on the body. During the four hot months they make five fires in a circle, and kneel between them with the head and legs and arms stretched towards the fires. The fires are kindled at noon with little heaps of cowdung cakes, and the penitent stays between them till they go out. They also have a block of wood with a hole through it, into which they insert the organ of generation and suspend it by chains in front and behind. They rub ashes on the body, from which they probably get their name of Khāki or dust-colour.

The Munjia Akhāra have a belt made of munj grass round the waist, and a little apron also of grass, which is hung from it, and passed through the legs. Formerly they wore no other clothes, but now they have a cloth. They also do penance between the fires.

The Kathias have a waist-belt of bamboo fibre, to which is suspended the wooden block for the purpose already described. Their name signifies wooden, and is probably given to them on account of this custom.

The Nirmohi carry a lota or brass vessel and a little cup, in which they receive alms.

The Nirbāni wear only a piece of string or rope round the waist, to which is attached a small strip of cloth passing through the legs. When begging, they carry a kawar or banghy, holding two baskets covered with cloth, and into this they put all their alms. They never remove the cloth, but plunge their hands into the basket at random when they want something to eat. They call the basket Kāmdhenu, the name of the cow which gave inexhaustible wealth. These Bairāgis commonly marry and accumulate property.

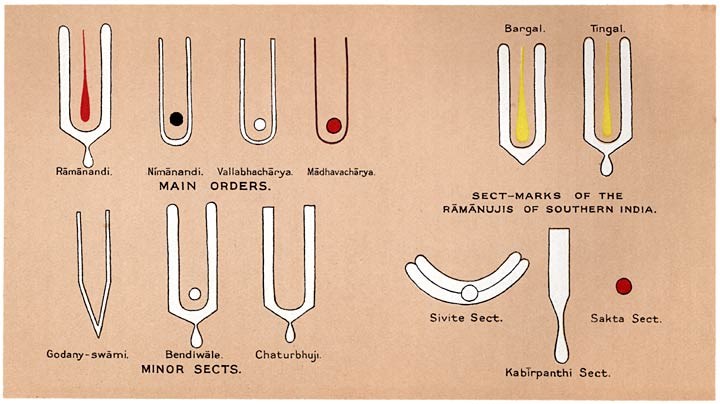

The Lasgari are soldiers, as the name denotes.106 They wear three straight lines of sandalwood up the forehead. It is said that on one occasion the Bairāgis were suddenly attacked by the Gosains when they had only made the white lines of the sect-mark, and they fought as they were. In consequence of this, they have ever since worn three white lines and no red one.

Others say that the Lasgari are a branch of the Digambari Akhāra, and that the Munjia and Kathia are branches of the Khāki Akhāra. They give three other Akhāras—Nīralankhi, Mahānirbāni and Santokhi—about which nothing is known.

10. The Dwāras.

Besides the Akhāras, the Bairāgis are said to have fifty-two Dwāras or doors, and every man must be a member of a Dwāra as well as of a Sampradāya and Akhāra. The Dwāras seem to have no special purpose, but in the case of Bairāgis who marry, they now serve as exogamous sections, so that members of the same Dwāra do not intermarry.

Examples of Tilaks or sect-marks worn on the forehead.

11. Initiation, appearance and customs.

A candidate for initiation has his head shaved, is invested with a necklace of beads of the tulsi or basil, and is taught a mantra or text relating to Vishnu by his preceptor. The initiation text of the Rāmānandis is said to be Om Rāmāya Nāmah, or Om, Salutation to Rāma. Om is a very sacred syllable, having much magical power. Thereafter the novice must journey to Dwārka in Gujarāt and have his body branded with hot iron or copper in the shape of Vishnu’s four implements: the chakra or discus, the guda or club, the shank or conch-shell and the padma or lotus. Sometimes these are not branded but are made daily on the arms with clay. The sect-mark should be made with Gopichandan or the milkmaid’s sandalwood. This is supposed to be clay taken from a tank at Dwārka, in which the Gopis or milkmaids who had been Krishna’s companions drowned themselves when they heard of his death. But as this can seldom be obtained any suitable whitish clay is used instead. The Bairāgis commonly let their hair grow long, after being shaved at initiation, to imitate the old forest ascetics. If a man makes a pilgrimage on foot to some famous shrine he may have his head shaved there and make an offering of his hair. Others keep their hair long and shave it only at the death of their guru or preceptor. They usually wear white clothes, and if a man has a cloth on the upper part of the body it should be folded over the shoulders and knotted at the neck. He also has a chimta or small pair of tongs, and, if he can obtain it, the skin of an Indian antelope, on which he will sit while taking his food. The skin of this animal is held to be sacred. Every Bairāgi before he takes his food should dip a sprig of tulsi or basil into it to sanctify it, and if he cannot get this he uses his necklace of tulsi-beads for the purpose instead. The caste abstain from flesh and liquor, but are addicted to the intoxicating drugs, gānja and bhāng or preparations of Indian hemp. A Hindu on meeting a Bairāgi will greet him with the phrase ‘Jai Sītārām,’ and the Bairāgi will answer, ‘Sītārām.’ This word is a conjunction of the names of Rāma and his consort Sīta. When a Bairāgi receives alms he will present to the giver a flower and a sprig of tulsi.

12. Recruitment of the order and its character.

A man belonging to any caste except the impure ones can be initiated as a Bairāgi, and the order is to a large extent recruited from the lower castes. Theoretically all members of the order should eat together; but the Brāhmans and other high castes belonging to it now eat only among themselves, except on the occasion of a Ghosti or special religious assembly, when all eat in common. As a matter of fact the order is a very mixed assortment of people. Many persons who lost their caste in the famine of 1897 from eating in Government poor-houses, joined the order and obtained a respectable position. Debtors who have become hopelessly involved sometimes find in it a means of escape from their creditors. Women of bad character, who have been expelled from their caste, are also frequently enrolled as female members, and in monasteries live openly with the men. The caste is also responsible for a good deal of crime. Not only is the disguise a very convenient one for thieves and robbers to assume on their travels, but many regular members of the order are criminally disposed. Nevertheless large numbers of Bairāgis are men who have given up their caste and families from a genuine impulse of self-sacrifice, and the desire to lead a religious life.

13. Social position and customs.

On account of their sanctity the Bairāgis have a fairly good social position, and respectable Hindu castes will accept cooked food from them. Brāhmans usually, but not always, take water. They act as gurus or spiritual guides to the laymen of all castes who can become Bairāgis. They give the Rām and Gopāl Mantras, or the texts of Rāma and Krishna, to their disciples of the three twice-born castes, and the Sheo Mantra or Siva’s text to other castes. The last is considered to be of smaller religious efficacy than the others, and is given to the lower castes and members of the higher ones who do not lead a particularly virtuous life. They invest boys with the sacred thread, and make the sect-mark on their foreheads. When they go and visit their disciples they receive presents, but do not ask them to confess their sins nor impose penalties.

If a mendicant Bairāgi keeps a woman it is stated that he is expelled from the community, but this rule does not seem to be enforced in practice. If he is detected in a casual act of sexual intercourse a fine should be imposed, such as feeding two or three hundred Bairāgis. The property of an unmarried Bairāgi descends to a selected chela or disciple. The bodies of the dead are usually burnt, but those of saints specially famous for their austerities or piety are buried, and salt is put round the body to preserve it. Such men are known as Bhakta.

14. Bairāgi monasteries.

The Bairāgis107 have numerous maths or monasteries, scattered over the country and usually attached to temples. The Math comprises a set of huts or chambers for the Mahant or superior and his permanent pupils; a temple and often the Samādhi or tomb of the founder, or of some eminent Mahant; and a Dharmsāla or charitable hostel for the accommodation of wandering members of the order, and of other travellers who are constantly visiting the temple. Ingress and egress are free to all, and, indeed, a restraint on personal liberty seems never to have entered into the conception of any Hindu religious legislator. There are, as a rule, a small number of resident chelas or disciples who are scholars and attendants on the superiors, and also out-members who travel over the country and return to the monastery as a headquarters. The monastery has commonly some small endowment in land, and the resident chelas go out and beg for alms for their common support. If the Mahant is married the headship may descend in his family; but when he is unmarried his successor is one of his disciples, who is commonly chosen by election at a meeting of the Mahants of neighbouring monasteries. Formerly the Hindu governor of the district would preside at such an election, but it is now, of course, left entirely to the Bairāgis themselves.

15. Married Bairāgis.

Large numbers of Bairāgis now marry and have children, and have formed an ordinary caste. The married Bairāgis are held to be inferior to the celibate mendicants, and will take food from them, but the mendicants will not permit the married Bairāgis to eat with them in the chauka or place purified for the taking of food. The customs of the married Bairāgis resemble those of ordinary Hindu castes such as the Kurmis. They permit divorce and the remarriage of widows, and burn the dead. Those who have taken to cultivation do not, as a rule, plough with their own hands. Many Bairāgis have acquired property and become landholders, and others have extensive moneylending transactions. Two such men who had acquired possession of extensive tracts of zamīndāri land in Chhattīsgarh, in satisfaction of loans made to the Gond zamīndārs, and had been given the zamīndāri status by the Marāthas, were subsequently made Feudatory Chiefs of the Nāndgaon and Chhuikhadan States. These chiefs now marry and the States descend in their families by primogeniture in the ordinary manner. As a rule, the Bairāgi landowners and moneylenders are not found to be particularly good specimens of their class.

Balāhi

1. General notice.

Balāhi. 108—A low functional caste of weavers and village watchmen found in the Nimār and Hoshangābād Districts and in Central India. They numbered 52,000 persons in the Central Provinces in 1911, being practically confined to the two Districts already mentioned. The name is a corruption of the Hindi bulāhi, one who calls, or a messenger. The Balāhis seem to be an occupational group, probably an offshoot of the large Kori caste of weavers, one of whose subdivisions is shown as Balāhi in the United Provinces. In the Central Provinces they have received accretions from the spinner caste of Katias, themselves probably a branch of the Koris, and from the Mahārs, the great menial caste of Bombay. In Hoshangābād they are known alternatively as Mahār, while in Burhānpur they are called Bunkar or weaver by outsiders. The following story which they tell about themselves also indicates their mixed origin. They say that their ancestors came to Nimār as part of the army of Rāja Mān of Jodhpur, who invaded the country when it was under Muhammadan rule. He was defeated, and his soldiers were captured and ordered to be killed.109 One of the Balāhis among them won the favour of the Muhammadan general and asked for his own freedom and that of the other Balāhis from among the prisoners. The Musalmān replied that he would be unable to determine which of the prisoners were really Balāhis. On this the Balāhi, whose name was Ganga Kochla, replied that he had an effective test. He therefore killed a cow, cooked its flesh and invited the prisoners to partake of it. So many of them as consented to eat were considered to be Balāhis and liberated; but many members of other castes thus obtained their freedom, and they and their descendants are now included in the community. The subcastes or endogamous groups distinctly indicate the functional character of the caste, the names given being Nimāri, Gannore, Katia, Kori and Mahār. Of these Katia, Kori and Mahār are the names of distinct castes, Nimāri is a local subdivision indicating those who speak the peculiar dialect of this tract, and the Gannore are no doubt named after the Rājpūt clan of that name, of whom their ancestors were not improbably the illegitimate offspring. The Nimāri Balāhis are said to rank lower than the rest, as they will eat the flesh of dead cattle which the others refuse to do. They may not take water from the village well, and unless a separate one can be assigned to them, must pay others to draw water for them. Partly no doubt in the hope of escaping from this degraded position, many of the Nimāri group became Christians in the famine of 1897. They are considered to be the oldest residents of Nimār. At marriages the Balāhi receives as his perquisite the leaf-plates used for feasts with the leavings of food upon them; and at funerals he takes the cloth which covers the corpse on its way to the burning-ghāt. In Nimār the Korkus and Balāhis each have a separate burying-ground which is known as Murghāta.110 The Katias weave the finer kinds of cloth and rank a little higher than the others. In Burhānpur, as already stated, the caste are known as Bunkar, and they are probably identical with the Bunkars of Khāndesh; Bunkar is simply an occupational term meaning a weaver.

2. Marriage.

The caste have the usual system of exogamous groups, some of which are named after villages, while the designations of others are apparently nicknames given to the founder of the clan, as Bagmār, a tiger-killer, Bhagoria, a runaway, and so on. They employ a Brāhman to calculate the horoscopes of a bridal couple and fix the date of their wedding, but if he says the marriage is inauspicious, they merely obtain the permission of the caste panchāyat and celebrate it on a Saturday or Sunday. Apparently, however, they do not consult real Brāhmans, but merely priests of their own caste whom they call Balāhi Brāhmans. These Brāhmans are, nevertheless, said to recite the Satya Nārāyan Katha. They also have gurus or spiritual preceptors, being members of the caste who have joined the mendicant orders; and Bhāts or genealogists of their own caste who beg at their weddings. They have the practice of serving for a wife, known as Gharjamai or Lamjhana. When the pauper suitor is finally married at the expense of his wife’s father, a marriage-shed is erected for him at the house of some neighbour, but his own family are not invited to the wedding.

After marriage a girl goes to her husband’s house for a few days and returns. The first Diwāli or Akha-tīj festival after the wedding must also be passed at the husband’s house, but consummation is not effected until the aina or gauna ceremony is performed on the attainment of puberty. The cost of a wedding is about Rs. 80 to the bridegroom’s family and Rs. 20 to the bride’s family. A widow is forbidden to marry her late husband’s brother or other relatives. At the wedding she is dressed in new clothes, and the foreheads of the couple are marked with cowdung as a sign of purification. They then proceed by night to the husband’s village, and the woman waits till morning in some empty building, when she enters her husband’s house carrying two water-pots on her head in token of the fertility which she is to bring to it.

3. Other customs.

Like the Mahārs, the Balāhis must not kill a dog or a cat under pain of expulsion; but it is peculiar that in their case the bear is held equally sacred, this being probably a residue of some totemistic observance. The most binding form of oath which they can use is by any one of these animals. The Balāhis will admit any Hindu into the community except a man of the very lowest castes, and also Gonds and Korkus. The head and face of the neophyte are shaved clean, and he is made to lie on the ground under a string-cot; a number of the Balāhis sit on this and wash themselves, letting the water drip from their bodies on to the man below until he is well drenched; he then gives a feast to the caste-fellows, and is considered to have become a Balāhi. It is reported also that they will receive back into the community Balāhi women who have lived with men of other castes and even with Jains and Muhammadans. They will take food from members of these religions and of any Hindu caste, except the most impure.

Balija

1. Origin and traditions.

Balija, Balji, Gurusthulu, Naidu.—A large trading caste of the Madras Presidency, where they number a million persons. In the Central Provinces 1200 were enumerated in 1911, excluding 1500 Perikis, who though really a subcaste and not a very exalted one of Balijas,111 claim to be a separate caste. They are mainly returned from places where Madras troops have been stationed, as Nāgpur, Jubbulpore and Raipur. The caste are frequently known as Naidu, a corruption of the Telugu word Nāyakdu, a prince or leader. Their ancestors are supposed to have been Nāyaks or kings of Madura, Tanjore and Vijayanagar. The traditional occupation of the caste appears to have been to make bangles and pearl and coral ornaments, and they have still a subcaste called Gāzulu, or a bangle-seller. In Madras they are said to be an offshoot of the great cultivating castes of Kamma and Kāpu and to be a mixed community recruited from these and other Telugu castes. Another proof of their mixed descent may be inferred from the fact that they will admit persons of other castes or the descendants of mixed marriages into the community without much scruple in Madras.112 The name of Balija seems also to have been applied to a mixed caste started by Bāsava, the founder of the Lingāyat sect of Sivites, these persons being known in Madras as Linga Balijas.

2. Marriage.

The Balijas have two main divisions, Desa or Kota, and Peta, the Desas or Kotas being those who claim descent from the old Balija kings, while the Petas are the trading Balijas, and are further subdivided into groups like the Gāzulu or bangle-sellers and the Periki or salt-sellers. The subdivisions are not strictly endogamous. Every family has a surname, and exogamous groups or gotras also exist, but these have generally been forgotten, and marriages are regulated by the surnames, the only prohibition being that persons of the same surname may not intermarry. Instances of such names are: Singiri, Gūdāri, Jadal, Sangnād and Dāsiri. In fact the rules of exogamy are so loose that an instance is known of an uncle having married his niece. Marriage is usually infant, and the ceremony lasts for five days. On the first day the bride and bridegroom are seated on a yoke in the pandal or marriage pavilion, where the relatives and guests assemble. The bridegroom puts a pair of silver rings on the bride’s toes and ties the mangal-sūtram or flat circular piece of gold round her neck. On the next three days the bridegroom and bride are made to sit on a plank or cot face to face with each other and to throw flowers and play together for two hours in the mornings and evenings. On the fourth day, at dead of night, they are seated on a cot and the jewels and gifts for the bride are presented, and she is then formally handed over to the bridegroom’s family. In Madras Mr. Thurston113 states that on the last day of the marriage ceremony a mock ploughing and sowing rite is held, and during this, the sister of the bridegroom puts a cloth over the basket containing earth, wherein seeds are to be sown by the bridegroom, and will not allow him to go on with the ceremony till she has extracted a promise that his first-born daughter shall marry her son. No bride-price is paid, and the remarriage of widows is forbidden.

3. Occupation and social status.

The Balijas bury their dead in a sitting posture. In the Central Provinces they are usually Lingāyats and especially worship Gauri, Siva’s wife. Jangams serve them as priests. They usually eat flesh and drink liquor, but in Chānda it is stated that both these practices are forbidden. In the Central Provinces they are mainly cultivators, but some of them still sell bangles and salt. Several of them are in Government service and occupy a fairly high social position.

In Madras a curious connection exists between the Kāpus and Balijas and the impure Māla caste. It is said that once upon a time the Kāpus and Balijas were flying from the Muhammadans and came to the northern Pallār river in high flood. They besought the river to go down and let them across, but it demanded the sacrifice of a first-born child. While the Kāpus and Balijas were hesitating, the Mālas who had followed them boldly sacrificed one of their children. Immediately the river divided before them and they all crossed in safety. Ever since then the Kāpus and Balijas have respected the Mālas, and the Balijas formerly even deposited the images of the goddess Gauri, of Ganesha, and of Siva’s bull with the Mālas, as the hereditary custodians of their gods.114

Bania

1. General notice.

Bania, Bāni, Vāni, Mahājan, Seth, Sāhukār.—The occupational caste of bankers, moneylenders and dealers in grain, ghī (butter), groceries and spices. The name Bania is derived from the Sanskrit vanij, a merchant. In western India the Banias are always called Vānia or Vāni. Mahājan literally means a great man, and being applied to successful Banias as an honorific title has now come to signify a banker or moneylender; Seth signifies a great merchant or capitalist, and is applied to Banias as an honorific prefix. The words Sāhu, Sao and Sāhukār mean upright or honest, and have also, curiously enough, come to signify a moneylender. The total number of Banias in the Central Provinces in 1911 was about 200,000, or rather over one per cent of the population. Of the above total two-thirds were Hindus and one-third Jains. The caste is fairly distributed over the whole Province, being most numerous in Districts with large towns and a considerable volume of trade.

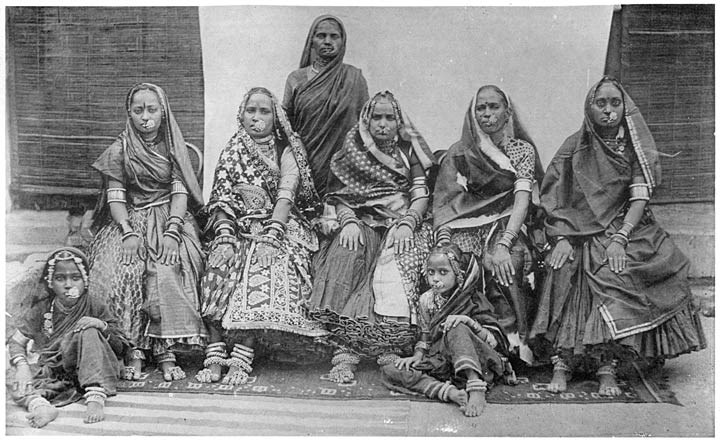

Group of Mārwāri Bania women.

2. The Banias a true caste: use of the name.

There has been much difference of opinion as to whether the name Bania should be taken to signify a caste, or whether it is merely an occupational term applied to a number of distinct castes. I venture to think it is necessary and scientifically correct to take it as a caste. In Bengal the word Banian, a corruption of Bania, has probably come to be a general term meaning simply a banker, or person dealing in money. But this does not seem to be the case elsewhere. As a rule the name Bania is used only as a caste name for groups who are considered both by themselves and outsiders to belong to the Bania caste. It may occasionally be applied to members of other castes, as in the case of certain Teli-Banias who have abandoned oil-pressing for shop-keeping, but such instances are very rare; and these Telis would probably now assert that they belonged to the Bania caste. That the Banias are recognised as a distinct caste by the people is shown by the number of uncomplimentary proverbs and sayings about them, which is far larger than in the case of any other caste.115 In all these the name Bania is used and not that of any subdivision, and this indicates that none of the subdivisions are looked upon as distinctive social groups or castes. Moreover, so far as I am aware, the name Bania is applied regularly to all the groups usually classified under the caste, and there is no group which objects to the name or whose members refuse to describe themselves by it. This is by no means always the case with other important castes. The Rāthor Telis of Mandla entirely decline to answer to the name of Teli, though they are classified under that caste. In the case of the important Ahīr or grazier caste, those who sell milk instead of grazing cattle are called Gaoli, but remain members of the Ahīr caste. An Ahīr in Chhattīsgarh would be called Rāwat and in the Maratha Districts Gowāri, but might still be an Ahīr by caste. The Barai caste of betel-vine growers and sellers is in some localities called Tamboli and not Barai; elsewhere it is known only as Pansāri, though the name Pansāri is correctly an occupational term, and, where it is not applied to the Barais, means a grocer or druggist by profession and not a caste. Bania, on the other hand, over the greater part of India is applied only to persons who acknowledge themselves and are generally recognised by Hindu society to be members of the Bania caste, and there is no other name which is generally applied to any considerable section of such persons. Certain of the more important subcastes of Bania, as the Agarwāla, Oswāl and Parwār, are, it is true, frequently known by the subcaste name. But the caste name is as often as not, or even more often, affixed to it. Agarwāla, or Agarwāla Bania, are names equally applied to designate this subcaste, and similarly with the Oswāls and Parwārs; and even so the subcaste name is only applied for greater accuracy and for compliment, since these are the best subcastes; the Bania’s quarter of a town will be called Bania Mahalla, and its residents spoken of as Banias, even though they may be nearly all Agarwāls or Oswāls. Several Rājpūt clans are similarly spoken of by their clan names, as Rāthor, Panwār, and so on, without the addition of the caste name Rājpūt. Brāhman subcastes are usually mentioned by their subcaste name for greater accuracy, though in their case too it is usual to add the caste name. And there are subdivisions of other castes, such as the Jaiswār Chamārs and the Somvansi Mehras, who invariably speak of themselves only by their subcaste name, and discard the caste name altogether, being ashamed of it, but are nevertheless held to belong to their parent castes. Thus in the matter of common usage Bania conforms in all respects to the requirements of a proper caste name.