полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

3. Their distinctive occupation.

The Banias have also a distinct and well-defined traditional occupation,116 which is followed by many or most members of practically every subcaste so far as has been observed. This occupation has caused the caste as a body to be credited with special mental and moral characteristics in popular estimation, to a greater extent perhaps than any other caste. None of the subcastes are ashamed of their traditional occupation or try to abandon it. It is true that a few subcastes such as the Kasaundhans and Kasarwānis, sellers of metal vessels, apparently had originally a somewhat different profession, though resembling the traditional one; but they too, if they once only sold vessels, now engage largely in the traditional Bania’s calling, and deal generally in grain and money. The Banias, no doubt because it is both profitable and respectable, adhere more generally to their traditional occupation than almost any great caste, except the cultivators. Mr. Marten’s analysis117 of the occupations of different castes shows that sixty per cent of the Banias are still engaged in trade; while only nineteen per cent of Brāhmans follow a religious calling; twenty-nine per cent of Ahīrs are graziers, cattle-dealers or milkmen; only nine per cent of Telis are engaged in all branches of industry, including their traditional occupation of oil-pressing; and similarly only twelve per cent of Chamārs work at industrial occupations, including that of curing hides. In respect of occupation therefore the Banias strictly fulfil the definition of a caste.

4. Their distinctive status.

The Banias have also a distinctive social status. They are considered, though perhaps incorrectly, to represent the Vaishyas or third great division of the Aryan twice-born; they rank just below Rājpūts and perhaps above all other castes except Brāhmans; Brāhmans will take food cooked without water from many Banias and drinking-water from all. Nearly all Banias wear the sacred thread; and the Banias are distinguished by the fact that they abstain more rigorously and generally from all kinds of flesh food than any other caste. Their rules as to diet are exceptionally strict, and are equally observed by the great majority of the subdivisions.

5. The endogamous divisions of the Banias.

Thus the Banias apparently fulfil the definition of a caste, as consisting of one or more endogamous groups or subcastes with a distinct name applied to them all and to them only, a distinctive occupation and a distinctive social status; and there seems no reason for not considering them a caste. If on the other hand we examine the subcastes of Bania we find that the majority of them have names derived from places,118 not indicating any separate origin, occupation or status, but only residence in separate tracts. Such divisions are properly termed subcastes, being endogamous only, and in no other way distinctive. No subcaste can be markedly distinguished from the others in respect of occupation or social status, and none apparently can therefore be classified as a separate caste. There are no doubt substantial differences in status between the highest subcastes of Bania, the Agarwāls, Oswāls and Parwārs, and the lower ones, the Kasaundhan, Kasarwāni, Dosar and others. But this difference is not so great as that which separates different groups included in such important castes as Rājpūt and Bhāt. It is true again that subcastes like the Agarwāls and Oswāls are individually important, but not more so than the Marātha, Khedawāl, Kanaujia and Maithil Brāhmans, or the Sesodia, Rāthor, Panwār and Jādon Rājpūts. The higher subcastes of Bania themselves recognise a common relationship by taking food cooked without water from each other, which is a very rare custom among subcastes. Some of them are even said to have intermarried. If on the other hand it is argued, not that two or three or more of the important subdivisions should be erected into independent castes, but that Bania is not a caste at all, and that every subcaste should be treated as a separate caste, then such purely local groups as Kanaujia, Jaiswār, Gujarāti, Jaunpuri and others, which are found in forty or fifty other castes, would have to become separate castes; and if in this one case why not in all the other castes where they occur? This would result in the impossible position of having forty or fifty castes of the same name, which recognise no connection of any kind with each other, and make any arrangement or classification of castes altogether impracticable. And in 1911 out of 200,000 Banias in the Central Provinces, 43,000 were returned with no subcaste at all, and it would therefore be impossible to classify these under any other name.

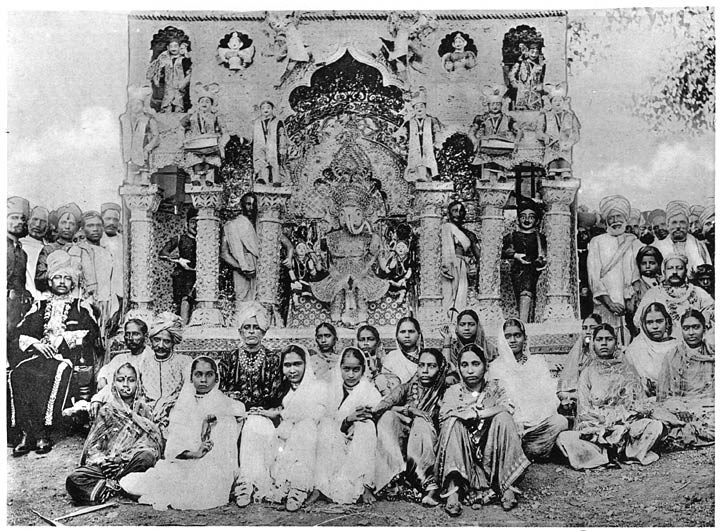

Image of the god Ganpati carried in procession.

6. The Banias derived from the Rājpūts.

The Banias have been commonly supposed to represent the Vaishyas or third of the four classical castes, both by Hindu society generally and by leading authorities on the subject. It is perhaps this view of their origin which is partly responsible for the tendency to consider them as several castes and not one. But its accuracy is doubtful. The important Bania groups appear to be of Rājpūt stock. They nearly all come from Rājputāna, Bundelkhand or Gujarāt, that is from the homes of the principal Rājūt clans. Several of them have legends of Rājpūt descent. The Agarwālas say that their first ancestor was a Kshatriya king, who married a Nāga or snake princess; the Nāga race is supposed to have signified the Scythian immigrants, who were snake-worshippers and from whom several clans of Rājpūts were probably derived. The Agarwālas took their name from the ancient city of Agroha or possibly from Agra. The Oswāls say that their ancestor was the Rājpūt king of Osnagar in Mārwār, who with his followers was converted by a Jain mendicant. The Nemas state that their ancestors were fourteen young Rājpūt princes who escaped the vengeance of Parasurāma by abandoning the profession of arms and taking to trade. The Khandelwāls take their name from the town of Khandela in Jaipur State of Rājputāna. The Kasarwānis say they immigrated from Kara Mānikpur in Bundelkhand. The origin of the Umre Banias is not known, but in Gujarāt they are also called Bāgaria from the Bāgar or wild country of the Dongarpur and Pertābgarh States of Rājputāna, where numbers of them are still settled; the name Bāgaria would appear to indicate that they are supposed to have immigrated thence into Gujarāt. The Dhūsar Banias ascribe their name to a hill called Dhūsi or Dhosi on the border of Alwar State. The Asātis say that their original home was Tīkamgarh State in Bundelkhand. The name of the Maheshris is held to be derived from Maheshwar, an ancient town on the Nerbudda, near Indore, which is traditionally supposed to have been the earliest settlement of the Yādava Rājpūts. The headquarters of the Gahoi Banias is said to have been at Kharagpur in Bundelkhand, though according to their own legend they are of mixed origin. The home of the Srimālis was the old town of Srimāl, now Bhinmāl in Mārwār. The Palliwāl Banias were from the well-known trading town of Pāli in Mārwār. The Jaiswāl are said to take their name from Jaisalmer State, which was their native country. The above are no doubt only a fraction of the Bania subcastes, but they include nearly all the most important and representative ones, from whom the caste takes its status and character. Of the numerous other groups the bulk have probably been brought into existence through the migration and settlement of sections of the caste in different parts of the country, where they have become endogamous and obtained a fresh name. Other subcastes may be composed of bodies of persons who, having taken to trade and prospered, obtained admission to the Bania caste through the efforts of their Brāhman priests. But a number of mixed groups of the same character are also found among the Brāhmans and Rājpūts, and their existence does not invalidate arguments derived from a consideration of the representative subcastes. It may be said that not only the Banias, but many of the low castes have legends showing them to be of Rājpūt descent of the same character as those quoted above; and since in their case these stories have been adjudged spurious and worthless, no greater importance should be attached to those of the Banias. But it must be remembered that in the case of the Banias the stories are reinforced by the fact that the Bania subcastes certainly come from Rājputāna; no doubt exists that they are of high caste, and that they must either be derived from Brāhmans or Rājpūts, or themselves represent some separate foreign group; but if they are really the descendants of the Vaishyas, the main body of the Aryan immigrants and the third of the four classical castes, it might be expected that their legends would show some trace of this instead of being unitedly in favour of their Rājpūt origin.

Colonel Tod gives a catalogue of the eighty-four mercantile tribes, whom he states to be chiefly of Rājpūt descent.119 In this list the Agarwāl, Oswāl, Srimāl, Khandelwāl, Palliwāl and Lād subcastes occur; while the Dhākar and Dhūsar subcastes may be represented by the names Dhākarwāl and Dusora in the lists. The other names given by Tod appear to be mainly small territorial groups of Rājputāna. Elsewhere, after speaking of the claims of certain towns in Rājputāna to be centres of trade, Colonel Tod remarks: “These pretensions we may the more readily admit, when we recollect that nine-tenths of the bankers and commercial men of India are natives of Mārudesh,120 and these chiefly of the Jain faith. The Oswāls, so termed from the town of Osi, near the Luni, estimate one hundred thousand families whose occupation is commerce. All these claim a Rājpūt descent, a fact entirely unknown to the European inquirer into the peculiarities of Hindu manners.”121

Similarly, Sir D. Ibbetson states that the Maheshri Banias claim Rājpūt origin and still have subdivisions bearing Rājpūt names.122 Elliot also says that almost all the mercantile tribes of Hindustān are of Rājpūt descent.123

It would appear, then, that the Banias are an offshoot from the Rājpūts, who took to commerce and learnt to read and write for the purpose of keeping accounts. The Chārans or bards are another literate caste derived from the Rājpūts, and it may be noticed that both the Banias and Chārans or Bhāts have hitherto been content with the knowledge of their own rude Mārwāri dialect and evinced no desire for classical learning or higher English education. Matters are now changing, but this attitude shows that they have hitherto not desired education for itself but merely as an indispensable adjunct to their business.

7. Banias employed as ministers in Rājpūt courts.

Being literate, the Banias were not infrequently employed as ministers and treasurers in Rājpūt states. Forbes says, in an account of an Indian court: “Beside the king stand the warriors of Rājpūt race or, equally gallant in the field and wiser far in council, the Wānia (Bania) Muntreshwars, already in profession puritans of peace, and not yet drained enough of their fiery Kshatriya blood.... It is remarkable that so many of the officers possessing high rank and holding independent commands are represented to have been Wānias.”124 Colonel Tod writes that Nunkurn, the Kachhwāha chief of the Shekhāwat federation, had a minister named Devi Das of the Bania or mercantile caste, and, like thousands of that caste, energetic, shrewd and intelligent.125 Similarly, Muhāj, the Jādon Bhātti chief of Jaisalmer, by an unhappy choice of a Bania minister, completed the demoralisation of the Bhātti state. This minister was named Sarūp Singh, a Bania of the Jain faith and Mehta family, whose descendants were destined to be the exterminators of the laws and fortunes of the sons of Jaisal.126 Other instances of the employment of Bania ministers are to be found in Rājpūt history. Finally, it may be noted that the Banias are by no means the only instance of a mercantile class formed from the Rājpūts. The two important trading castes of Khatri and Bhātia are almost certainly of Rājpūt origin, as is shown in the articles on those castes.

8. Subcastes.

The Banias are divided into a large number of endogamous groups or subcastes, of which the most important have been treated in the annexed subordinate articles. The minor subcastes, mainly formed by migration, vary greatly in different provinces. Colonel Tod gave a list of eighty-four in Rājputāna, of which eight or ten only can be identified in the Central Provinces, and of thirty mentioned by Bhattachārya as the most common groups in northern India, about a third are unknown in the Central Provinces. The origin of such subcastes has already been explained. The main subcastes may be classified roughly into groups coming from Rājputāna, Bundelkhand and the United Provinces. The leading Rājputāna groups are the Oswāl, Maheshri, Khandelwāl, Saitwāl, Srimāl and Jaiswāal. These groups are commonly known as Mārwāri Bania or simply Mārwāri. The Bundelkhand or Central India subcastes are the Gahoi, Golapūrab, Asāti, Umre and Parwār;127 while the Agarwāl, Dhusar, Agrahari, Ajudhiabāsi and others come from the United Provinces. The Lād subcaste is from Gujarāt, while the Lingāyats originally belonged to the Telugu and Canarese country. Several of the subcastes coming from the same locality will take food cooked without water from each other, and occasionally two subcastes, as the Oswāl and Khandelwāl, even food cooked with water or katchi. This practice is seldom found in other good castes. It is probably due to the fact that the rules about food are less strictly observed in Rājputāna.

The elephant-headed god Ganpati. His conveyance is a rat, which can be seen as a little blob between his feet.

9. Hindu and Jain subcastes: divisions among subcastes.

Another classification may be made of the subcastes according as they are of the Hindu or Jain religion; the important Jain subcastes are the Oswāl, Parwār, Golapūrab, Saitwāl and Charnāgar, and one or two smaller ones, as the Baghelwāl and Samaiya. The other subcastes are principally Hindu, but many have a Jain minority, and similarly the Jain subcastes return a proportion of Hindus. The difference of religion counts for very little, as practically all the non-Jain Banias are strict Vaishnava Hindus, abstain entirely from any kind of flesh meat, and think it a sin to take animal life; while on their side the Jains employ Brāhmans for certain purposes, worship some of the local Hindu deities, and observe the principal Hindu festivals. The Jain and Hindu sections of a subcaste have consequently, as a rule, no objection to taking food together, and will sometimes intermarry. Several of the important subcastes are subdivided into Bīsa and Dasa, or twenty and ten groups. The Bīsa or twenty group is of pure descent, or twenty carat, as it were, while the Dasas are considered to have a certain amount of alloy in their family pedigree. They are the offspring of remarried widows, and perhaps occasionally of still more irregular unions. Intermarriage sometimes takes place between the two groups, and families in the Dasa group, by living a respectable life and marrying well, improve their status, and perhaps ultimately get back into the Bīsa group. As the Dasas become more respectable they will not admit to their communion newly remarried widows or couples who have married within the prohibited degrees, or otherwise made a mésalliance, and hence a third inferior group, called the Pacha or five, is brought into existence to make room for these.

10. Exogamy and rules regulating marriage.

Most subcastes have an elaborate system of exogamy. They are either divided into a large number of sections, or into a few gotras, usually twelve, each of which is further split up into subsections. Marriage can then be regulated by forbidding a man to take a wife from the whole of his own section or from the subsection of his mother, grandmothers and even greatgrandmothers. By this means the union of persons within five or more degrees of relationship either through males or females is avoided, and most Banias prohibit intermarriage, at any rate nominally, up to five degrees. Such practices as exchanging girls between families or marrying two sisters are, as a rule, prohibited. The gotras or main sections appear to be frequently named after Brāhman Rīshis or saints, while the subsections have names of a territorial or titular character.

11. Marriage customs.

There is generally no recognised custom of paying a bride- or bridegroom-price, but one or two instances of its being done are given in the subordinate articles. On the occasion of betrothal, among some subcastes, the boy’s father proceeds to the girl’s house and presents her with a māla or necklace of gold or silver coins or coral, and a mundri or silver ring for the finger. The contract of betrothal is made at the village temple and the caste-fellows sprinkle turmeric and water over the parties. Before the wedding the ceremony of Benaiki is performed; in this the bridegroom, riding on a horse, and the bride on a decorated chair or litter, go round their villages and say farewell to their friends and relations. Sometimes they have a procession in this way round the marriage-shed. Among the Mārwāri Banias a toran or string of mango-leaves is stretched above the door of the house on the occasion of a wedding and left there for six months. And a wooden triangle with figures perched on it to represent sparrows is tied over the door. The binding portion of the wedding is the procession seven times round the marriage altar or post. In some Jain subcastes the bridegroom stands beside the post and the bride walks seven times round him, while he throws sugar over her head at each turn. After the wedding the couple are made to draw figures out of flour sprinkled on a brass plate in token of the bridegroom’s occupation of keeping accounts. It is customary for the bride’s family to give sīdha or uncooked food sufficient for a day’s consumption to every outsider who accompanies the marriage party, while to each member of the caste provisions for two to five days are given. This is in addition to the evening feasts and involves great expense. Sometimes the wedding lasts for eight days, and feasts are given for four days by the bridegroom’s party and four days by the bride’s. It is said that in some places before a Bania has a wedding he goes before the caste panchāyat and they ask him how many people he is going to invite. If he says five hundred, they prescribe the quantity of the different kinds of provisions which he must supply. Thus they may say forty maunds (3200 lbs.) of sugar and flour, with butter, spices, and other articles in proportion. He says, ‘Gentlemen, I am a poor man; make it a little less’; or he says he will give gur or cakes of raw cane sugar instead of refined sugar. Then they say, ‘No, your social position is too high for gur; you must have sugar for all purposes.’ The more guests the host invites the higher is his social consideration; and it is said that if he does not maintain this his life is not worth living. Sometimes the exact amount of entertainment to be given at a wedding is fixed, and if a man cannot afford it at the time he must give the balance of the feasts at any subsequent period when he has money; and if he fails to do this he is put out of caste. The bride’s father is often called on to furnish a certain sum for the travelling expenses of the bridegroom’s party, and if he does not send this money they do not come. The distinctive feature of a Bania wedding in the northern Districts is that women accompany the marriage procession, and the Banias are the only high caste in which they do this. Hence a high-caste wedding party in which women are present can be recognised to be a Bania’s. In the Marātha Districts women also go, but here this custom obtains among other high castes. The bridegroom’s party hire or borrow a house in the bride’s village, and here they erect a marriage-shed and go through the preliminary ceremonies of the wedding on the bridegroom’s side as if they were at home.

12. Polygamy and widow-marriage.

Polygamy is very rare among the Banias, and it is generally the rule that a man must obtain the consent of his first wife before taking a second one. In the absence of this precaution for her happiness, parents will refuse to give him their daughter. The remarriage of widows is nominally prohibited, but frequently occurs, and remarried widows are relegated to the inferior social groups in each subcaste as already described. Divorce is also said to be prohibited, but it is probable that women put away for adultery are allowed to take refuge in such groups instead of being finally expelled.

13. Disposal of the dead and mourning.

The dead are cremated as a rule, and the ashes are thrown into a sacred river or any stream. The bodies of young children and of persons dying from epidemic disease are buried. The period of mourning must be for an odd number of days. On the third day a leaf plate with cooked food is placed on the ground where the body was burnt, and on some subsequent day a feast is given to the caste. Rich Banias will hire people to mourn. Widows and young girls are usually employed, and these come and sit before the house for an hour in the morning and sometimes also in the evening, and covering their heads with their cloths, beat their breasts and make lamentations. Rich men may hire as many as ten mourners for a period of one, two or three months. The Mārwāris, when a girl is born, break an earthen pot to show that they have had a misfortune; but when a boy is born they beat a brass plate in token of their joy.

14. Religion: the god Ganpati or Ganesh.

Nearly all the Banias are Jains or Vaishnava Hindus. An account of the Jain religion has been given in a separate article, and some notice of the retention of Hindu practices by the Jains is contained in the subordinate article on Parwār Bania. The Vaishnava Banias no less than the Jains are strongly averse to the destruction of animal life, and will not kill any living thing. Their principal deity is the god Ganesh or Ganpati, the son of Mahādeo and Pārvati, who is the god of good-luck, wealth and prosperity. Ganesh is represented in sculpture with the head of an elephant and riding on a rat, though the rat is now covered by the body of the god and is scarcely visible. He has a small body like a child’s with a fat belly and round plump arms. Perhaps his body signifies that he is figured as a boy, the son of Pārvati or Gauri. In former times grain was the main source of wealth, and from the appearance of Ganesh it can be understood why he is the god of overflowing granaries, and hence of wealth and good fortune. The elephant is a sacred animal among Hindus, and that on which the king rides. To have an elephant was a mark of wealth and distinction among Banias, and the Jains harness the cars of their gods to elephants at their great rath or chariot festival. Gajpati or ‘lord of elephants’ is a title given to a king; Gajānand or ‘elephant-faced’ is an epithet of the god Ganesh and a favourite Hindu name. Gajvīthi or the track of the elephant is a name of the Milky Way, and indicates that there is believed to be a divine elephant who takes this course through the heavens. The elephant eats so much grain that only a comparatively rich man can afford to keep one; and hence it is easy to understand how the attribute of plenty or of wealth was associated with the divine elephant as his special characteristic. Similarly the rat is connected with overflowing granaries, because when there is much corn in a Hindu house or store-shed there will be many rats; thus a multitude of rats implied a rich household, and so this animal too came to be a symbol of wealth. The Hindus do not now consider the rat sacred, but they have a tenderness for it, especially in the Marātha country. The more bigoted of them objected to rats being poisoned as a means of checking plague, though observation has fully convinced them that rats spread the plague; and in the Bania hospitals, formerly maintained for preserving the lives of animals, a number of rats were usually to be found. The rat, in fact, may now be said to stand to Ganpati in the position of a disreputable poor relation. No attempt is made to deny his existence, but he is kept in the background as far as possible. The god Ganpati is also associated with wealth of grain through his parentage. He is the offspring of Siva or Mahādeo and his wife Devi or Gauri. Mahādeo is in this case probably taken in his beneficent character of the deified bull; Devi in her most important aspect as the great mother-goddess is the earth, but as mother of Ganesh she is probably imagined in her special form of Gauri, the yellow one, that is, the yellow corn. Gauri is closely associated with Ganesh, and every Hindu bridal couple worship Gauri Ganesh together as an important rite of the wedding. Their conjunction in this manner lends colour to the idea that they are held to be mother and son. In Rājputāna Gauri is worshipped as the corn goddess at the Gangore festival about the time of the vernal equinox, especially by women. The meaning of Gauri, Colonel Tod states, is yellow, emblematic of the ripened harvest, when the votaries of the goddess adore her effigies, in the shape of a matron painted the colour of ripe corn. Here she is seen as Ana-pūrna (the corn-goddess), the benefactress of mankind. “The rites commence when the sun enters Aries (the opening of the Hindu year), by a deputation to a spot beyond the city to bring earth for the image of Gauri. A small trench is then excavated in which barley is sown; the ground is irrigated and artificial heat supplied till the grain germinates, when the females join hands and dance round it, invoking the blessings of Gauri on their husbands. The young corn is then taken up, distributed and presented by the females to the men, who wear it in their turbans.”128 Thus if Ganesh is the son of Gauri he is the offspring of the bull and the growing corn; and his genesis from the elephant and the rat show him equally as the god of full granaries, and hence of wealth and good fortune. We can understand therefore how he is the special god of the Banias, who formerly must have dealt almost entirely in grain, as coined money had not come into general use.