полная версия

полная версияThe Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races

66

A. von Humboldt, Examen critique de l'Histoire et de la Géographie du N. C., vol. ii. p. 129-130.

The same opinion is expressed by Mr. Humboldt in his Personal Narrative. London, 1852, vol. i. p. 296. – H.

67

Speaking of the habit of tattooing among the South Sea Islanders, Mr. Darwin says that even girls who had been brought up in missionaries' houses, could not be dissuaded from this practice, though in everything else, they seemed to have forgotten the savage instincts of their race. "The wives of the missionaries tried to prevent them, but a famous operator having arrived from the South, they said: 'We really must have just a few lines on our lips, else, when we grow old, we shall be so ugly.'" —Journal of a Naturalist, vol. ii. p. 208. – H.

68

For the latest details, see Mr. Gustave d'Alaux's articles in the Revue des Deux Mondes, 1853.

69

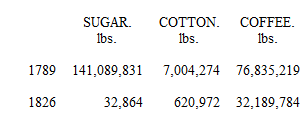

The subjoined comparison of the exports of Haytien staple products may not be uninteresting to many of our readers, while it serves to confirm the author's assertion. I extract it from a statistical table in Mackenzie's report to the British government, upon the condition of the then republic (now empire). Mr. Mackenzie resided there as special envoyé several years, for the purpose of collecting authentic information for his government, and his statements may therefore be relied upon. (Notes on Hayti, vol. ii. note FF. London, 1830.)

It will be perceived, from these figures, that the decrease is greatest in that staple which requires the most laborious cultivation. Thus, sugar requires almost unremitting toil; coffee, comparatively little. All branches of industry have fearfully decreased; some of them have ceased entirely; and the small and continually dwindling commerce of that wretched country consists now mainly of articles of spontaneous growth. The statistics of imports are in perfect keeping with those of exports. (Op. cit., vol. ii. p. 183.) As might be expected from such a state of things, the annual expenditure in 1827 was estimated at a little more than double the amount of the annual revenue! (Ibid., "Finance.")

That matters have not improved under the administration of that Most Gracious, Most Christian monarch, the Emperor Faustin I., will be seen by reference to last year's Annuaire de la Revue del deux Mondes, "Haiti," p. 876, et seq., where some curious details about his majesty and his majesty's sable subjects will be found.

70

Upon this subject, consult Prichard, d'Orbigny, and A. de Humboldt.

71

I recollect having read, several years ago, in a Jesuit missionary journal (I forget its name and date, but am confident that the authority is a reliable one), a rather ludicrous account of an instance of this kind. One of the fathers, who had a little isolated village under his charge, had occasion to leave his flock for a time, and his place, unfortunately, could not be replaced by another. He therefore called the most promising of his neophytes, and committed to their care the domestic animals and agricultural implements with which the society had provided the newly-converted savages, then left them with many exhortations and instructions. His absence being prolonged beyond the period anticipated, the Indians thought him dead, and instituted a grand funeral feast in his honor, at which they slaughtered all the oxen, and roasted them by fires made of the ploughs, hoe-handles, etc.; and he arrived just in time to witness the closing scenes of this mourning ceremony. – H.

72

Consult, among others, Carus: Uber ungleiche Befähigung der vershiedenen Menschen-stämme für höhere geistige Entwickelung. Leipzig, 1849, p. 96 et passim.

73

Prichard, Natural History of Man, vol. ii.

See particularly the recent researches of E. G. Squier, published in 1847, under the title: Observations on the Aboriginal Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, and also in various late reviews and other periodicals.

74

The very singular construction of these tumuli, and the numerous utensils found in them, occupy at this moment the penetration and talent of American antiquaries. I shall have occasion, in a subsequent volume, to express an opinion as to their value in the inquiries about a former civilization; at present, I shall only say that their almost incredible antiquity cannot be called in question. Mr. Squier is right in considering this proved by the fact merely, that the skeletons exhumed from these tumuli crumble into dust as soon as exposed to the atmosphere, although the condition of the soil in which they lie, is the most favorable possible; while the human remains under the British cromlichs, and which have been interred for at least eighteen centuries, are perfectly solid. It is easily conceived, therefore, that between the first possessors of the American soil and the Lenni-Lenape and other tribes, there is no connection. Before concluding this note, I cannot refrain from praising the industry and skill manifested by American scholars in the study of the antiquities of their immense continent. To obviate the difficulties arising from the excessive fragility of the exhumed skulls, many futile attempts were made, but the object was finally accomplished by pouring into them a bituminous preparation which instantly solidifies and thus preserves the osseous parts. This process, which requires many precautions, and as much skill as promptitude, is said to be generally successful.

75

Ancient India required, on the part of its first white colonists, immense labor of cultivation and improvement. (See Lassen, Indische Alterthumskunde, vol. i.) As to Egypt, see what Chevalier Bunsen, Ægypten's Stelle in der Weltgeschichte, says of the fertilization of the Fayoum, that gigantic work of the earliest sovereigns.

76

"Why have accidental circumstances always prevented some from rising, while they have only stimulated others to higher attainments?" —Dr. Kneeland's Introd. to Hamilton Smith's Nat. Hist. of Man, p. 95. – H.

77

Salvador, Histoire des Juifs.

78

M. Saint-Marc Girardin, Revue des Deux Mondes.

79

See, upon this often-debated subject, the opinion – somewhat acerbly expressed – of a learned historian and philologist: —

"A great number of writers have suffered themselves to be persuaded that the country made the nation; that the Bavarians and Saxons were predestined, by the nature of their soil, to become what they are to-day; that Protestantism belonged not to the regions of the south; and that Catholicism could not penetrate to those of the north; and many similar things. Men who interpret history according to their own slender knowledge, their narrow hearts, and near-sighted minds, would, by the same reasoning, make us believe that the Jews had possessed such and such qualities – more or less clearly understood – because they inhabited Palestine, and not India or Greece. But, if these philosophers, so dextrous in proving whatever flatters their notions, were to reflect that the Holy Land contained, in its limited compass, peoples of the most dissimilar religions and modes of thinking, that between them, again, and their present successors, there is the utmost difference conceivable, although the country is still the same; they would understand how little influence, upon the character and civilization of a nation has the country they inhabit." – Ewald, Geschichte des Volkes Israel, vol. i. p. 259.

80

Although the success of the Chinese missions has not been proportionate to the self-devoting zeal of its laborers, there yet are, in China, a vast number of believers in the true faith. M. Huc tells us, in the relation of his journey, that, in almost every place where he and his fellow-traveller stopped, they could perceive, among the crowds that came to stare at the two "Western devils" (as the celestials courteously call us Europeans), men making furtively, and sometimes quite openly, the sign of the cross. Among the nomadic hordes of the table-lands of Central Asia, the number of Christians is much greater than among the Chinese, and much greater than is generally supposed. (See Annals of the Propagation of the Faith, No. 135, et seq.) – H.

81

The tutelary divinity was generally a typification of the national character. A commercial or maritime nation, would worship Mercury or Neptune; an aggressive and warlike one, Hercules or Mars; a pastoral one, Pan; an agricultural one, Ceres or Triptolemus; one sunk in luxury, as Corinth, would render almost exclusive homage to Venus.

As the author observes, all ancient governments were more or less theocratical. The regulations of castes among the Hindoos and Egyptians were ascribed to the gods, and even the most absolute monarch dared not, and could not, transgress the limits which the immortals had set to his power. This so-called divine legislation often answered the same purpose as the charters of modern constitutional monarchies. The authority of the Persian kings was confined by religious regulations, and this has always been the case with the sultans of Turkey. Even in Rome, whose population had a greater tendency for the positive and practical, than for the things of another world, we find the traces of theocratical government. The sibylline books, the augurs, etc., were something more than a vulgar superstition; and the latter, who could stop or postpone the most important proceedings, by declaring the omens unpropitious, must have possessed very considerable political influence, especially in the earlier periods. The rude, liberty-loving tribes of Scandinavia, Germany, Gaul, and Britain, were likewise subjected to their druids, or other priests, without whose permission they never undertook any important enterprise, whether public or private. Truly does our author observe, that Christianity came to deliver mankind from such trammels, though the mistaken or interested zeal of some of its servants, has so often attempted, and successfully, to fasten them again. How ill adapted Christianity would be, even in a political point of view, for a theocratical formula, is well shown by Mr. Guizot, in his Hist. of Civilization, vol. i. p. 213. – H.

82

I have already pointed out, in my introduction (p. 41-43), some of the fatal consequences that spring from that doctrine. It may not, however, be out of place here to mention another. The communists, socialists, Fourrierites, or whatever names such enemies to our social system assume, have often seduced the unwary and weak-minded, by the plausible assertion that they wished to restore the social system of the first Christians, who held all goods in common, etc. Many religious sectaries have created serious disturbances under the same pretence. It seems, indeed, reasonable to suppose, that if Christianity had given its exclusive sanction to any particular social and political system, it must have been that which the first Christian communities adopted. – H.

83

See note on page 188. – H.

84

Natural History of Man, p. 390. London, 1843.

85

Synopsis of the Indian Tribes of North America.

86

Had I desired to contest the accuracy of the assertions upon which Mr. Prichard bases his arguments in this case, I should have had in my favor the weighty authority of Mr. De Tocqueville, who, in speaking of the Cherokees, says: "What has greatly promoted the introduction of European habits among these Indians, is the presence of so great a number of half-breeds. The man of mixed race – participating as he does, to a certain extent, in the enlightenment of the father, without, however, entirely abandoning the savage manner of the mother – forms the natural link between civilization and barbarism. As the half-breeds increase among them, we find savages modify their social condition, and change their manners." (Dem. in Am., vol. i. p. 412.) Mr. De Tocqueville ends by predicting that the Cherokees and Creeks, albeit they are half-breeds, and not, as Mr. Prichard affirms, pure aborigines, will, nevertheless, disappear before the encroachments of the whites.

87

"When four pieces of cards were laid before them, each having a number pronounced once in connection with it, they will, after a re-arrangement of the pieces, select any one named by its number. They also play at domino, and with so much skill as to triumph over biped opponents, whining if the adversary plays a wrong piece, or if they themselves are deficient in the right one." —Vest. of Cr., p. 236. – H.

88

In those portions of the present France, over one million and a half of the inhabitants speak German. The pure Gauls in the Landes have not yet learned the French language, and speak a peculiar – probably their original —patois.

89

With the exception of Normandy.

90

See p. 183.

91

I am not aware that any writer has ever presumed to doubt this fact except Mr. Guizot, who dismisses it with a sneer. Fortunately, a sneer is not an argument, though it often has more weight.

92

Hazlitt's translation, vol. i. p 21. New York, 1855. – H.

93

A careful comparison of Mr. Guizot's views with those expressed by Count Gobineau upon this interesting subject convinced me that the differences of opinion between these two investigators required a more careful and minute examination than the author has thought necessary. With this view, I subjoin further extracts from the celebrated "History of Civilization in Europe," from which, I think, it will appear that few of the great truths comprised in the definition of civilization have escaped the penetration and research of the illustrious writer, but that, being unable to divest himself of the idea of unity of civilization, he has necessarily fallen into an error, with which a great metaphysician justly charges so many reasoners. "It is hard," says Locke, speaking of the abuse of words, "to find a discourse written on any subject, especially of controversy, wherein one shall not observe, if he read with attention, the same words (and those commonly the most material in the discourse, and upon which the argument turns) used sometimes for one collection of simple ideas, and sometimes for another… A man, in his accompts with another, might with as much fairness, make the characters of numbers stand sometimes for one, and sometimes for another collection of units (e. g., this character, 3, stand sometimes for three, sometimes for four, and sometimes for eight), as, in his discourse or reasoning, make the same words stand for different collections of simple ideas."

Mr. Guizot opens his first lecture by declaring his intention of giving a "general survey of the history of European civilization, of its origin, its progress, its end, its character. I say European civilization, because there is evidently so striking a uniformity in the civilization of the different states of Europe, as fully to warrant this appellation. Civilization has flowed to them all from sources so much alike, it is so connected in them all – notwithstanding the great differences of time, of place, and circumstances – by the same principles, and it tends in them all to bring about the same results, that no one will doubt of there being a civilization essentially European."

Here, then, Mr. Guizot acknowledges one great truth contended for in this volume; he virtually recognizes the fact that there may be other civilizations, having different origins, a different progress, different characters, different ends.

"At the same time, it must be observed, that this civilization cannot be found in – its history cannot be collected from – the history of any single state of Europe. However similar in its general appearance throughout the whole, its variety is not less remarkable, nor has it ever yet developed itself completely in any particular country. Its characteristic features are widely spread, and we shall be obliged to seek, as occasion may require, in England, in France, in Germany, in Spain, for the elements of its history."

This is precisely the idea expressed in my introduction, that according to the character of a nation, its civilization manifests itself in various ways; in some, by perfection in the arts, useful or polite; in others, by development of political forms, and their practical application, etc. If I had then wished to support my opinion by a great authority, I should, assuredly, have quoted Mr. Guizot, who, a few pages further on, says: —

"Wherever the exterior condition of man becomes enlarged, quickened, and improved; wherever the intellectual nature of man distinguishes itself by its energy, brilliancy, and its grandeur; wherever these signs occur, notwithstanding the gravest imperfections in the social system, there man proclaims and applauds a civilization."

"Notwithstanding the gravest imperfections in the social system," says Mr. Guizot, yet in the series of hypotheses, quoted in the text, in which he attempts a negative definition of civilization, by showing what civilization is not, he virtually makes a political form the test of civilization.

In another passage, again, he says that civilization "is a course for humanity to run – a destiny for it to accomplish. Nations have transmitted, from age to age, something to their successors which is never lost, but which grows, and continues as a common stock, and will thus be carried on to the end of all things. For my part (he continues), I feel assured that human nature has such a destiny; that a general civilization pervades the human race; that at every epoch it augments; and that there, consequently, is a universal history of civilization to be written."

It must be obvious to the reader who compares these extracts, that Mr. Guizot expresses a totally distinct idea or collection of ideas in each.

First, the civilization of a particular nation, which exists "wherever the intellectual nature of man distinguishes itself by its energy, brilliancy, and grandeur." Such a civilization may flourish, "notwithstanding the greatest imperfections in the social system."

Secondly, Mr. Guizot's beau-idéal of the best, most perfect civilization, where the political forms insure the greatest happiness, promote the most rapid – yet well-regulated – progress.

Thirdly, a great system of particular civilizations, as that of Europe, the various elements of which "are connected by the same principles, and tend all to bring about the same general results."

Fourthly, a supposed general progress of the whole human race toward a higher state of perfection.

To all these ideas, provided they are not confounded one with another, I have already given my assent. (See Introduction, p. 51.) With regard to the latter, however, I would observe that it by no means militates against a belief in the intellectual imparity of races, and the permanency of this imparity. As in a society composed of individuals, all enjoy the fruits of the general progress, though all have not contributed to it in equal measure, and some not at all: so, in that society, of which we may suppose the various branches of the human family to be the members, even the inferior participate more or less in the benefits of intellectual labor, of which they would have been incapable. Because I can transport myself with almost the swiftness of a bird from one place to another, it does not follow that – though I profit by Watt's genius – I could have invented the steam-engine, or even that I understand the principles upon which that invention is based. – H.

94

W. Von Humboldt, Ueber die Kawi-Sprache auf der Insel Java; Einleitung, vol. i. p. 37. Berlin. "Die Civilization ist die Vermenschlichung der Völker in ihren äusseren Einrichtungen und Gebräuchen, und der darauf Bezug habenden inneren Gesinnung."

95

William Von Humboldt. "Die Kultur fügt dieser Veredlung des gesellschaftlichen Zustandes Wissenschaft und Kunst hinzu."

96

W. Von Humboldt, op. cit., p. 37: "Wenn wir in unserer Sprache Bildung sagen, so meinen wir damit etwas zugleich Höheres und mehr Innerlicheres, nämlich die Sinnesart, die sich aus der Erkenntniss und dem Gefühle des gesammten geistigen und sittlichen Streben harmonish auf die Empfindung und den Charakter ergiesst."

As nothing can exceed the difficulty of rendering an abstract idea from the French into English, except to transmit the same from German into French, and as if all these processes must be undergone, the identity of the idea is greatly endangered, I have thought proper to translate at once from the original German, and therefore differ somewhat from Mr. Gobineau, who gives it thus: "L'homme formé, c'est-à-dire, l'homme qui, dans sa nature, possède quelque chose de plus haut, de plus intime à la fois, c'est-à-dire, une façon de comprendre qui répand harmonieusement sur la sensibilité et le charactère les impressions qu'elle reçoit de l'activité intellectuelle et morale dans son ensemble." I have taken great pains to express clearly Mr. Von Humboldt's idea, and have therefore amplified the word Sinnesart, which has not its precise equivalent in English. – Trans.

97

See page 154.

98

Mr. Klemm (Allgemeine Culturgeschichte der Menschheit, Leipzig, 1849) adopts, also, a division of all races into two categories, which he calls respectively the active and the passive. I have not had the advantage of perusing his book, and cannot, therefore, say whether his idea is similar to mine. It would not be surprising that, in pursuing the same road, we should both have stumbled over the same truth.

99

The translator has here permitted himself a deviation from the original. Mr. Gobineau, to express his idea, borrows from the symbolism of the Hindoos, where the feminine principle is represented by Prakriti, and the masculine by Purucha, and calls the two categories of races respectively feminine and masculine. But as he "thereby wishes to express nothing but a mutual fecundation, without ascribing any superiority to either," and as the idea seems fully rendered by the words used in the translation, the latter have been thought preferable, as not so liable to misrepresentation and misconception. – H.

100

See a quotation from De Tocqueville to the same effect, p. 77.

101

One striking observation, in connection with this fact, Mr. Gobineau has omitted to make, probably not because it escaped his sagacity, but because he is himself a Roman Catholic. Wherever the Teutonic element in the population is predominant, as in Denmark, Sweden, Holland, England, Scotland, Northern Germany, and the United States, Protestantism prevails; wherever, on the contrary, the Germanic element is subordinate, as in portions of Ireland, in South America, and the South of Europe, Roman Catholicism finds an impregnable fortress in the hearts of the people. An ethnographical chart, carefully made out, would indicate the boundaries of each in Christendom. I do not here mean to assert that the Christian religion is accessible only to certain races, having already emphatically expressed my opinion to the contrary. I feel firmly convinced that a Roman Catholic may be as good and pious a Christian as a member of any other Christian Church whatever, but I see in this fact the demonstration of that leading characteristic of the Germanic races – independence of thought, which incites them to seek for truth, even in religion, for themselves; to investigate everything, and take nothing upon trust.